Icy gusts of wind off Lake Erie added to the chill and dampness as carriage loads of family members, friends and other mourners gathered at the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railway depot in Monroe, Mich.

The group waited to receive two black velvet–draped caskets for the funeral procession to nearby Woodland Cemetery. It was Jan. 8, 1878, and the remains of 27-year-old Boston Custer and his 18-year-old nephew Harry Armstrong “Autie” Reed were finally coming home from Montana Territory.

Family members initially thought their remains would be returned in July 1877 with those of the officers slain at the June 25–26, 1876, Battle of the Little Bighorn. But Boston and Autie had been civilians, and Secretary of War George W. McCrary refused to authorize or fund their transport.

Second Lt. Frederick S. Calhoun (a Custer in-law), Francis “Frank” D. Yates (a family friend) and Yates’ father-in-law William H. Brown (proprietor of Brown’s Hotel at Fort Laramie, Wyoming Territory) interceded. They arranged for the decomposed remains to be placed in pine coffins, conveyed by wagon from the battlefield to Cheyenne and shipped via express to Chicago, where George Chase, secretary to the superintendent of the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern, received the remains and then accompanied them to Monroe.

FROSTY GRAVES

Gravediggers had managed to break through the frosty crust and down into the sandy soil to a standard depth. The open graves were waiting when two horse-drawn hearses arrived with the caskets for the short graveside service that brought closure to Boston’s parents Emanuel and Maria Custer, their daughter Margaret (“Maggie”) and surviving son, Nevin.

It was the family’s final act after hearing the terrible news 18 months earlier of the annihilation of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and 262 officers and men of his 7th U.S. Cavalry command by waves of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors. While the nation mourned their loss, Monroe’s 5,000 residents felt the blow most acutely.

The Custer family’s association with Monroe began in 1842 when Emanuel, encouraged by relatives, briefly rented a house there. After his horses were stolen, he returned to his hometown of New Rumley, Ohio. George, 3 years old at the time, later lived periodically in Monroe with half-sister Lydia Ann Kirkpatrick Reed and husband. George attended school in Monroe and ultimately convinced his father to move there permanently in 1863, enabling his little sister, Maggie, to benefit from better schools.

JUDGE’S DAUGHTER

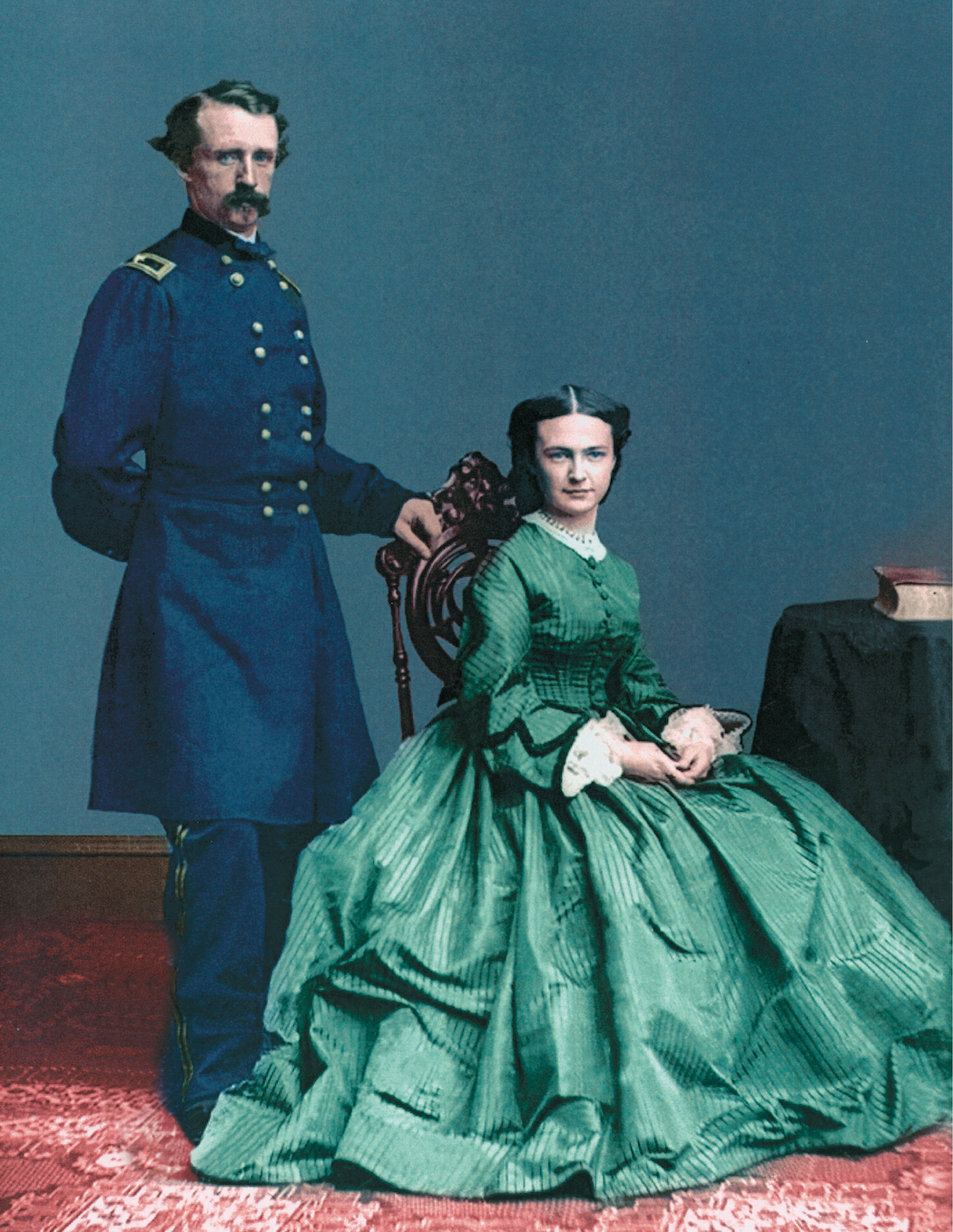

Elizabeth Clift “Libbie” Bacon, born in Monroe in 1842, was the daughter of well-respected Judge Daniel Bacon. When George, home on leave in 1862 during the Civil War, was formally introduced to and expressed an interest in Libbie, her father frowned on any relationship, as Emanuel was a mere farmer/blacksmith.

As George advanced in rank, Judge Bacon finally acquiesced. The couple married in 1864 at Monroe’s First Presbyterian Church. Frequent return visits after the war, and George’s 1871 joint purchase of a local farm with brother Nevin and their respective wives, further cemented the family ties to Monroe.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Monroe first learned of the disaster in Montana Territory midmorning on July 6, 1876, when an editor of The Adrian Daily Times and Expositor distributed handbills in town. As word spread, many businesses closed, church bells tolled and residents gathered, speaking in hushed voices as a general gloom enveloped the city with the loss of “their boys.”

Nevin Custer was out of town when he got the news. “I had been down in Ohio to see about some land and was driving back to Monroe,” he recalled in a 1910 interview with a Topeka, Kan., newspaper. “I pulled into Hastings, Ohio, for the night, and when the mail came in, there was news of the battle. I didn’t believe it at first, but I drove on home as fast as the team could travel, and there I found Monroe all draped in mourning.”

MONROE IN MOURNING

Around daybreak on July 6 at Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory, officers formally conveyed the deaths of Lt. Col. George Custer, brother Captain Thomas Custer, brother-in-law 1st Lt. James Calhoun (who had married Maggie Custer in 1871), youngest brother, Boston Custer, and favorite nephew Autie Reed to widows Libbie and Maggie and Reed’s unmarried sister Emma.

Some wives, including Libbie, claimed to have had premonitions of impending doom, but that hardly lessened the shock, sadness and disbelief thrust on these women. Delivering the grim news were 20th U.S. Infantry Captain William S. McCaskey, post surgeon Major Johnson V.D. Middleton and 6th U.S. Infantry 2nd Lt. Charles L. Gurley.

The Custers’ maid answered the knock on the door. The visitors asked her to awaken the household and gather the women in the parlor. On hearing the news, Libbie dissolved into tears, her face turning ashen. Regaining her composure, she draped a shawl across her shoulders to ward off the morning chill, then “the first lady of the regiment” courageously accompanied the trio as they notified the other officers’ widows—all 14 of them.

Sobbing uncontrollably, Maggie, who stayed with sister-in-law Libbie whenever the regiment was away, cried out as they left the house, “Is there no message for me?” There was no message; they were all gone—killed in a short fight, leaving a fraternity of spouses with disquietude, financial insecurity and an uncertain future.

“ALL MY BOYS GONE”

Compounding Libbie’s sadness was a letter received several days later from family friend Florence Boyd in Monroe that described Father Custer as being “in tears most of the time,” and Mother Custer, who was already frail and in poor health, repeatedly crying, “How can I bear it—all my boys gone?”

Soon thereafter Libbie, Maggie, the unmarried Emma Reed and the other widows at Fort Lincoln were told to vacate the post. Libbie had her limited household furnishings and the colonel’s personal possessions transported to Monroe, then found homes for his hunting hounds. (On the death of Custer’s beloved dog Cardigan, its new owner had the body stuffed and put on public display in Minneapolis.)

Libbie, in mourning dress and veil, manages a slight smile. (Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.)

The surviving officers at Fort Lincoln purchased the colonel’s horse Dandy from the government and presented him to Libbie, who in turn gave him to her father-in-law. Dandy lived out his life on the 116-acre Custer farm, the aging Father Custer on occasion riding him in town parades.

Monroe residents scheduled a memorial service on Aug. 13, 1876, at First Methodist Episcopal Church (present-day St. Paul’s United Methodist Church) that honored the five Custer family members and close family friend Captain George W. Yates, who also died in the battle. Among the participating multidenominational clergy, the Rev. David Casler best described its impact: “If one of these heroes had fallen, we had felt like…mingling our tears with theirs; but how shall we utter fitting words when…a whole constellation goes out from a single home.”

RETRIEVING REMAINS

These and other eulogies comforted the family, including the recently returned Libbie, Maggie and Emma Reed. They had reached Monroe about a week earlier by special railcar via the Northern Pacific, Chicago & North Western and, finally, Michigan Central.

In July 1877 a military party returned to the battlefield to rebury the enlisted men and retrieve the officers’ remains. Scavenging animals, insects and exposure to intense sun and heat had since hastened decomposition. The recovery detail placed the remains of 11 officers in pine coffins for transport to Fort Lincoln and forwarding from there on request in caskets to their respective families.

Libbie requested to have her husband’s body sent to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. The remains of Tom Custer, George Yates and James Calhoun, along with those of 1st Lts. Donald McIntosh and Algernon Emory Smith, were shipped to Kansas for reburial at Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery.

On the morning of Aug. 3, 1877, a Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific express car arrived at Leavenworth City’s Union Depot bearing five caskets. Pallbearers bore the caskets to the post chapel, where an honor guard from the 23rd Infantry stood vigil and remained for a viewing the next day by family, friends and visitors.

Among the principal mourners was Maggie Custer Calhoun. Since leaving Fort Lincoln, she had been living in Monroe. Her doctor had advised her not to travel, as grief over husband James’ death had brought on headaches, fever and dizzy spells. Regardless, she joined family members—including brother-in-law Lt. Fred Calhoun of the 14th Infantry, on leave from his post at Camp Robinson, Neb.—and other grieving widows for the late afternoon graveside service.

DARK DECLARATION

Post chaplain the Rev. John Woart officiated at the Episcopal Protestant service, which culminated as pallbearers placed the caskets on five artillery caissons for the procession to the cemetery. Fred Calhoun, who had been at Camp Robinson three months earlier when Crazy Horse surrendered, had declared at the time, “The massacre of the entire Indian race would not repay my loss of last summer.”

While serving as adjutant at Camp Robinson on September 5, a month after the reburial ceremony, he passed along the order to turn over Crazy Horse to the officer of the day at the guardhouse. As his men carried out that order, Crazy Horse resisted, and a bayonet-wielding guard mortally wounded the Lakota prisoner. “He was forgiven for murder,” Calhoun later gloated, “but killed for impudence.”

Back in Monroe Libbie shared her late parents’ home with Maggie and parents-in-law Emanuel and Maria Custer. Donned perpetually in the mourning attire of a bereaved widow and desiring seclusion, Libbie faced a shrinking bank account, self-support in a small town and the obligation to care for Father and Mother Custer.

What thoughts entered their minds while coping with the tragedy? Did they console each other even as they struggled to understand the events? Did they reminisce about more pleasant times when the family last was together? Did they suffer from depression, despondency or melancholy? Were there tears, anger, avoidance, thoughts unspoken? We can surmise they grieved together.

FINANCIAL DIFFICULTIES

On arriving home by train in August 1876 Libbie was overcome with emotion when greeted by friends and collapsed. Maggie continued to suffer emotionally. Letters from relatives and friends expressed comfort and sympathy, but their words failed to assuage the family’s intense pain and sorrow. How could they? Unlike present-day reporters, the media respected personal tragedy and did not encroach on Libbie’s privacy, allowing her time and space to mourn.

Libbie on her wedding day, Feb. 9, 1864, at Monroe’s First Presbyterian Church. (Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.)

Despite her remorse, Libbie had to grapple with financial realities. She received several settlements from George’s insurance policies, but one that named his parents as beneficiaries had lapsed due to a missed June premium. Libbie beseeched the insurance company to honor the policy. “I feel that he [George] has left them [his parents] to me as a final legacy,” she wrote. “It is with the most intense regret that I find myself so situated financially that I cannot provide for them as I would wish. They are very old and poor, and the mother is a confirmed invalid.”

The company acquiesced, but George’s indebtedness amounted to more than Libbie could repay, requiring her to sell the colonel’s thoroughbred Frogtown, for $220, and his half-interest in the farm to Nevin, for $725. George’s government pension of $30 per month remained woefully inadequate to cover expenses.

Considering employment, Libbie soon realized Monroe offered women few opportunities. So in late December 1876 she wrote a friend at the U.S. Pension Agency, hoping the incoming administration of President Rutherford B. Hayes might be helpful.

Mistakenly, her appeal came to the attention of President Ulysses S. Grant, who encouraged an appointment for her. On learning Grant was involved, Libbie wrote her friend, “You will excuse me, I know, when I tell you how much I dread thinking that General Grant would be led to believe that I would ask or accept from him anything in the world.”

A GRUDGE AGAINST GRANT

It was Grant who in April 1876 had detained Custer in Washington after the colonel testified before Congress regarding trader post kickbacks tied to Secretary of War William W. Belknap, a personal friend of the president. Belknap had resigned while under investigation and was later impeached. An infuriated Grant had refused to meet with Custer and even had him arrested when he left town without permission.

After the Little Bighorn debacle Grant did not communicate with or extend sympathies to Father and Mother Custer, Libbie or any of the other widows. His first public statement regarding the battle appeared in the Sept. 2, 1876, edition of The New York Herald when he commented, “I regard Custer’s massacre as a sacrifice of troops, brought on by Custer himself, that was wholly unnecessary—wholly unnecessary.”

The family never forgave Grant. In 1910, during the dedication of the Custer statue in Monroe, Nevin Custer spoke of the rift. “If it hadn’t been for U.S. Grant, George Custer would have been alive today,” he told a reporter. “It was the Belknap investigation, you know. Oh, I won’t say any more. It makes my blood boil, and I’m liable to say something that I hadn’t ought. But we don’t like Grant around here.” It was Grant’s failed peace policy that had prompted a military solution and the Great Sioux War of 1876.

In late spring 1877, at the behest of relatives, Libbie moved to Newark, N.J., and soon found steady employment in New York City as a secretary for the newly established Society of Decorative Arts.

THE BEGINNING OF CLOSURE

Closure for Libbie began the morning of Oct. 10 when her husband’s remains—which since early August had been stored in a receiving vault in Poughkeepsie, N.Y.—were placed aboard the steamer Mary Powell and transported up the Hudson River to West Point. Thousands of people lined the riverbanks, and passing ships lowered their flags to half-mast.

Once the boat docked, pallbearers transferred the colonel’s metallic casket to an elegant four-horse caisson. Several military units led a procession to the chapel, where the casket lay in state. At 2 p.m. West Point Superintendent Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield escorted Libbie to the Episcopal service, conducted by post chaplain Dr. John Forsyth. Emanuel Custer, Maggie Custer Calhoun and other bereaved relatives and friends followed them.

The emotional, tear-filled ceremony concluded with another winding procession to the post cemetery. The brief graveside service included three volleys of echoing gunfire from a cadre of academy cadets.

Throughout her personal ordeal Libbie sought pension increases for “my widows,” as she often referred to sister-in-law Maggie, Nettie Smith, Annie Yates and other wives of officers killed at the Little Bighorn. Her success was incremental, but by late August 1880 Libbie had finally settled any remaining indebtedness to creditors for 10 cents on the dollar, leaving her with $118.63.

AUTHOR AND SPEAKER

By the end of 1882 Congress had increased her government pension to $50 per month. Soon thereafter Libbie left her position with the Society of Decorative Arts and began a life of self-reliance, continuing to defend her famous husband’s reputation, enhance his image and refute his critics. She gave lectures and wrote three books—”Boots and Saddles” (1885), “Tenting on the Plains” (1887) and “Following the Guidon” (1890). Congress boosted her pension to $100 per month in 1890, cementing her independence.

Personal tragedy continued to beset Libbie. Mother Custer died on Jan. 14, 1882. Her obituary in The Monroe Democrat five days later noted that “though possessed of a remarkably strong constitution, Mrs. Custer has been a sufferer for a number of years.…Her health was seriously impaired previous to the death of her three sons, son-in-law and grandson in the battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.…The mother’s heart was broken, and she died gradually, mourning the tragic death of her illustrious sons.”

Ten years later the politically opinionated and deeply religious Emanuel Custer, who had also never recovered from the loss of his sons, died suddenly at Nevin’s farm, along the River Raisin northwest of Monroe. Father Custer had moved there in 1882.

Maggie Custer Calhoun returned to Monroe with Libbie, Emma Reed and Annie Yates. After the death of Mother Custer, Maggie studied dramatic elocution in Detroit and performed across the northern United States until accepting appointment as Michigan’s state librarian in 1891.

Two years later she resigned to resume her dramatic readings. Sometime during her travels she met John H. Maugham, whom she married on July 2, 1903. Diagnosed with cancer the following year, she died in 1910 and was buried in the family plot at Monroe’s Woodland Cemetery.

PRESIDENTIAL Visit

Libbie continued to stand vigil over her husband’s image, safeguarding his portrayal in print and in stone. She deemed a bust of George atop a granite base at his gravesite unacceptable and replaced it with an obelisk in 1906. On June 4, 1910, with no less a personage than President William Howard Taft in attendance, city officials in Monroe unveiled the aforementioned statue of a mounted George Custer.

As Libbie mingled with well-wishers, her memory may have wandered back nearly a half-century to Feb. 9, 1864, when she and George were married at First Presbyterian Church, in sight of the statue on Washington and 1st streets. As the grand statue caused traffic congestion, city fathers twice relocated it to safer, more accessible locations. It stands by the river on the corner of North Monroe Street and West Elm Avenue.

Emma Reed, who lived with her family in Monroe, married her uncle by marriage Lt. Fred Calhoun in 1879. She traveled to various posts with her husband, who retired in 1890 and died in 1904. After his death Emma returned to Monroe, and in 1938 she moved to Boston to live with her daughter, Ella May Calhoun. Emma Reed Calhoun died in 1949.

The sudden, violent death of Annie Yates in New York City on Dec. 9, 1914, was a severe blow for Libbie. Yates was her last close associate from Fort Lincoln. On learning of the death of her husband, Captain George Yates, at the Little Bighorn, Annie had turned prematurely gray virtually overnight. The couple had had three children. Annie was originally from Philadelphia.

After living in Monroe with Libbie, she relocated to Carlisle, Pa., and taught for many years at Carlisle Indian Industrial School before moving to Brooklyn, N.Y. While traveling home after visiting a friend, Annie switched from a crowded subway car to one less congested, snagged her dress and was crushed between the train and the platform.

CUSTER FAMILY LEGACY

Nevin Custer, exempted from military service due to poor health, reflected on the family fortunes in a 1910 interview. “We’ve had some pretty rough times, we Custers,” he said. “Name sort of stands for fight.…I’m the only one left of the brothers now, and though it’s nice, of course, to have George honored as he deserved…I can’t imagine George as a fighting man half so well as I see him hoeing corn down in Ohio. I guess that’s because I’m a farmer.” Nevin died at his daughter’s home in 1915 after falling ill while shopping in downtown Monroe. Libbie attended the service, but she never again returned to the place of her birth.

Veterans from both sides gathered in 1926 to mark the 50th anniversary of the battle with sham fights along the Little Bighorn. Some of Custer’s Crow scouts and other notables attended, but not Libbie. She feared reliving its associated agonies, though she personally responded to hundreds of letters received afterward —a two-year process.

The statue of a mounted George Custer overlooks North Monroe Street. (Stan “Tex” Banash.)

On April 4, 1933, Elizabeth Bacon Custer suffered a heart attack and died in New York City. Buried beside her husband at West Point, Libbie was finally reunited with her Autie after nearly 57 years of gallantly defending his reputation and image.

The burials of George, his brothers and in-laws brought closure, but the tragedy left the family and residents of Monroe with lingering emotional and psychological scars. The stigma of that traumatic day on the Little Bighorn remained embedded in their lives. It is for the historically minded to spiritually embrace their anguish.

Chicago-based Stan “Tex” Banash, the author of Roadside History of Illinois (2013), sourced many contemporary newspaper accounts and thanks Charmaine Wawrzyniec of the Monroe County Library System for her help. Suggested for further reading: General Custer’s Libbie, by Lawrence A. Frost (1976); the article “Going Home to Monroe,” by Anita Smyntek, in the May 2011 issue of Greasy Grass; and the article “Libbie Custer: ‘A Wounded Thing Must Hide,’” by Paul Andrew Hutton, in the June 2012 issue of Wild West.

This story originally appeared in the June 2017 print edition of Wild West.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.