Quite a lot, it turns out, if they’ve been “missing” for the last 150 years.

Sitting in a red-cushioned armchair, a young woman with magenta-streaked black hair and a silver nose ring thumbs through the latest issue of People magazine. Before long, she’s dozing, feet propped on an ottoman. Nearby, a 30-something guy in a baseball cap sits at a computer, watching a rock concert as he plays air guitar, a beatific smile on his face. A few seats away, a teenage boy in a purple T-shirt is navigating between a NASCAR-inspired computer game on one screen and Facebook on the other. Every so often he frowns, and frantically hits the keys, posting a message on “SweetTreat’s” wall.

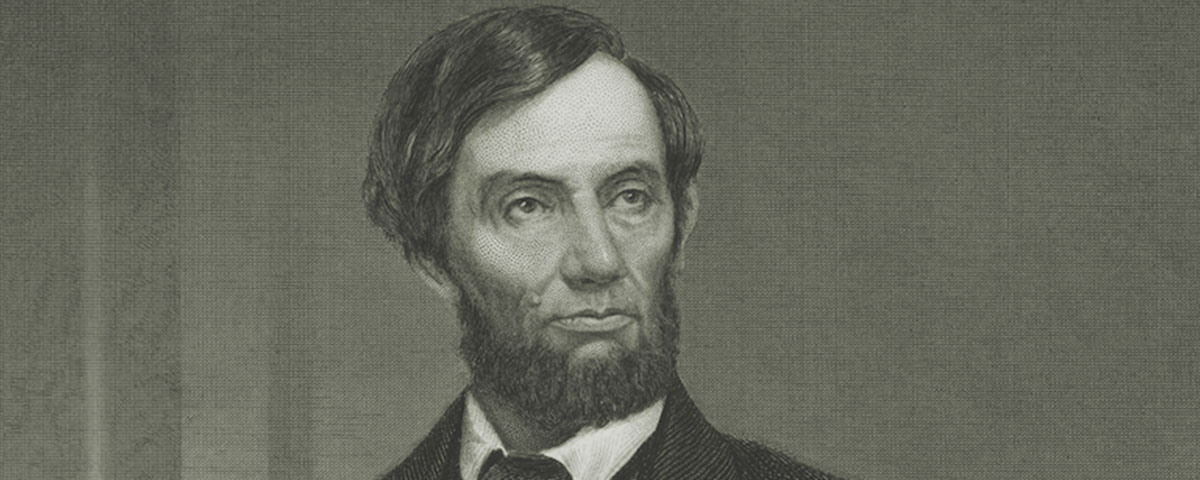

It’s a quiet summer afternoon at the Southworth Library on Main Street in the village of Dryden, N.Y. The room is a new addition to the century-old library, completed just a few months ago. It’s called Lincoln Center because Abraham Lincoln paid for it—on February 12, 2009.

The story of how Lincoln contributed $3.44 million to the library on the anniversary of his 200th birthday includes his son Robert, an obscure congressman, the Works Progress Administration from the Great Depression and the Union Army. It illustrates history’s power to reverberate through time and space in unpredictable ways.

“It seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected,” Abraham Lincoln wrote on August 23, 1864. Eleven weeks before Election Day, Lincoln knew that Americans were sick of a war that seemed to drag on forever. Union armies were stalled outside Richmond and Atlanta as the slaughter continued without sign of victory. In late August, the Democrats nominated George McClellan, a general Lincoln had fired, and ran him on a platform of negotiated peace with the Confederates.

“I am going to be beaten,” the president told a visitor, “and unless some great change takes place, badly beaten.”

But a great change did take place on September 1: General William Tecumseh Sherman sent a six-word telegram—“Atlanta is ours, and fairly won.” The North celebrated and Lincoln’s prospects improved. Nonetheless, when Election Day arrived on November 8, the outcome was uncertain.

That night, Lincoln walked through a driving rain to the War Department, where voting results were arriving by telegram. The early results were promising. McClellan was ahead in New Jersey, but Lincoln led in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. New York was undecided but leaning toward Lincoln. Results from the west arrived sluggishly, as the storm slowed transmissions. The president went to bed not knowing who won.

The next day, Lincoln returned to the War Department. Results pouring in showed the president had carried every state except New Jersey, Delaware and Kentucky, with 55 percent of the vote. He was thrilled to learn that his soldiers had voted for him by a margin of nearly 4 to 1.

After midnight a crowd of supporters led by a brass band marched to the White House with lanterns and banners, cheering the president. Lincoln appeared in an upstairs window and delivered a speech. It was not the usual vapid victory speech with thanks to supporters, contributors and, of course, the devoted wife. Lincoln had more important thoughts to express.

“It has long been a grave question whether any government, not too strong for the liberties of its people, can be strong enough to maintain its own existence in great emergencies,” he began. “On this point, the present rebellion brought our republic to a severe test; and a presidential election occurring in regular course during the rebellion added not a little to the strain.”

No country in history, he told the crowd, had ever held a presidential election during a civil war. “But the election was a necessity. We cannot have a free government without elections; and if the rebellion could force us to forego or postpone a national election, it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us.”

The unprecedented election, he continued, proved “how strong we still are” and showed that “he who is most devoted to the Union, and most opposed to treason, can receive most of the people’s votes.”

The election was over but not the war, he said, and he exhorted his countrymen to “re-unite in a common effort to save our common country.” Lincoln ended by urging the crowd to do what it most wanted to do— cheer: “Let me close by asking three hearty cheers for our brave soldiers and seamen and their gallant and skillful commanders.”

The speech was, said John Hay, Lincoln’s secretary and future biographer, “one of the weightiest and wisest of all his discourses.” After Lincoln delivered it, the speech disappeared for 50 years.

How One Small Town Came To Own Lincoln’s Speech

In 1867, two years after Lincoln’s assassination, Congress passed a bill creating a commission to design a fitting monument to the fallen president. The commission hired an architect who designed a baroque structure garnished with 37 statues, six of them equestrian. That was too ornate and expensive, and the project died. In the early years of the new century, an Illinois senator introduced six consecutive bills to create a memorial. All of them failed. Finally, in 1911, Congress passed a bill to create the Lincoln Memorial, and President William Howard Taft signed it into law on Lincoln’s 102nd birthday.

Five years later, as the memorial was under construction, Robert Todd Lincoln, the president’s son, sent a gift to Congressman John W. Dwight, of Dryden, N.Y. The House Republican whip had performed the arm-twisting and deal-cutting necessary to shepherd the memorial bill to passage.

“My Dear Mr. Dwight, You know my gratitude to you for your effective work in the House in the legislation providing for the erection of the Lincoln Memorial,” Robert Lincoln wrote, “but I wish you to have something tangible as a testimonial of my feeling.”

As Lincoln’s only child to survive to adulthood, Robert Lincoln had inherited his father’s papers, 20,000 or more. For his gift to Dwight, he dipped into that priceless treasure trove.

“In the book by Noah Brooks entitled In Lincoln’s Time,” Robert wrote in his letter to Dwight, “you will find an account of a public demonstration at the White House immediately after the presidential election of 1864, at which my father made a speech….I am sending you the original manuscript used by him on that occasion.”

Dwight was no longer serving in Congress when Robert Lincoln sent him the speech, but like many ex-congressmen, he didn’t return home. He lived in Washington and worked as president of a railroad. But he hadn’t forgotten his hometown of Dryden, N.Y., and he told his wife that he wanted her to donate the Lincoln speech to the Southworth Library when he died.

He died in January 1928. That summer, his widow, Emma Childs Dwight, traveled to Dryden to present the speech to the library. “It was desired for the Lincoln Memorial in Washington,” a local newspaper reported, “but Mr. Dwight wanted his townspeople to have this prized relic of the Civil War president.”

The board of the Southworth Library gratefully accepted the gift. But what should they do with it? They weren’t sure, so they put it in a safe deposit box in the First National Bank of Dryden.

There it sat, safe but unseen, for eight years.

“Lost” Speech Found

In 1929, into a year after Lincoln’s speech arrived in Dryden, the stock market crashed, plunging the United States the worst depression in its history. Three years later, American voters replaced President Herbert Hoover with Franklin D. Roosevelt, who promised to do something about the economy.

What Roosevelt did was spend money. FDR’s New Deal created countless programs that hired the unemployed to build roads, dams, post offices and parks. But not everyone employed by the New Deal performed manual labor. One agency, the Federal Writers Project, put thousands of unemployed writers to work, many of them on the American Guide series—producing guidebooks on all 48 states. In 1936, one of those writers, Roland P. Gray, drove into Dryden, looking for something, anything, to include in the New York guidebook.

An English professor and folklorist, Gray poked around Dryden, talking to folks. He heard a rumor about the Lincoln speech. He wandered over to the bank to see if it was true. What Gray saw at the bank prompted a four-page press release by the Works Progress Administration—the Writers Project’s parent agency—and a story in the New York Times:

LOST MANUSCRIPT OF LINCOLN FOUND; WPA Research Editor Gets 4-Page Text of Re-election Address of 1864.

The Manuscript Goes On Sale

The people of Dryden must have laughed at that headline. Lost manuscript? They knew exactly where it was. They also knew why it was there: To put the original manuscript on display required special conditions and security, all of which cost more than they could afford. At Gray’s urging, the board allowed five photographic copies to be made of the speech and Robert Lincoln’s letter to John Dwight. One of those copies was placed on permanent exhibition in the Southworth Library; the others were forwarded to various archives, including the Library of Congress. The original document went right back to the bank vault.

Forty years later, it was taken out and exhibited for a few days during the nation’s bicentennial. After that, it went back to the bank.

And there it sat for another three decades. By 2008, the library’s trustees were desperate for expansion funds. The building’s footprint had remained virtually unchanged since the doors first opened in 1894. To make the library a vital community resource, they decided to sell their most valuable asset. They selected Christie’s to manage the public auction of the manuscript dubbed the “1864 Election Victory Speech.” It’s exceedingly rare for an authentic, handwritten Lincoln manuscript to go on sale. To highlight the significance of the auction, it was held on February 12, 2009, Lincoln’s 200th birthday. Everyone hoped for a sale in excess of $3 million.

At the Southworth Library that day, Diane Pamel, the director, remembers a cake arrived decorated with a picture of Lincoln, and a local book club scheduled a discussion of Garry Wills’ Lincoln at Gettysburg. But the discussion stopped so everyone could watch the auction live online on the library’s computers. It didn’t take long.

“Before you could blink, “Pamel recalls, “the Christie’s auctioneer said something like ‘a phone bid for three-and-a-half million, going once, twice, sold,’ and that was it. Everybody applauded and…well, we said, Hooray, louder than the usual library voice allowed.” To be exact, the manuscript and letter from Robert Lincoln sold for $3.44 million, a sum said to be a record for an American historic document.

Meanwhile, the book club members just wanted to get back to their discussion of Lincoln at Gettysburg. “We were talking about a book on Lincoln we’d been reading,” Pamel says. “It was very—I guess you could say it was very dry. Most of the ladies didn’t like it. That’s why some of them were grumpy about taking time out to watch the auction and eat the cake. They wanted to keep talking. We have our best discussions about books we hate.”

Sixteen months later, the Southworth Library dedicated the new wing that Lincoln’s speech funded. “We’ve doubled our space, added programs, created a beautiful, relaxing environment for reading and attracted new patrons,” Pamel says, sitting in her new office. “I think Abe would have liked seeing this. He loved to read, you know, especially with his children.”

And where is Lincoln’s speech now? Good question. Whoever paid $3.44 million for it has chosen to remain anonymous and has given no indication of where the manuscript might be. “I just hope the speech stayed in the country,” Pamel says.

Original Manuscript Text:

“Response to a Serenade”

It has long been a grave question whether any government, not too strong for the liberties of its people, can be strong enough to maintain its own existence, in great emergencies.

On this point the present rebellion brought our republic to a severe test, and a presidential election occurring in regular course during the rebellion added not a little to the strain. If the loyal people, united, were put to the utmost of their strength by the rebellion, must they not fail when divided, and partially paralized (sic) by a political war among themselves?

But the election was a necessity.

We can not have free government without elections; and if the rebellion could force us to forego, or postpone a national election, it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us. The strife of the election is but human nature practically applied to the facts of the case. What has occurred in this case, must ever recur in similar cases. Human nature will not change. In any future great national trial, compared with the men of this, we shall have as weak, and as strong; as silly and as wise; as bad and good. Let us, therefore, study the incidents of this, as philosophy to learn wisdom from, and none of them as wrongs to be revenged.

But the election, along with its incidental, and undesirable strife, has done good too. It has demonstrated that a people’s government can sustain a national election, in the midst of a great civil war. Until now it has not been known to the world that this was a possibility. It shows how sound and how strong we still are. It shows that, even among candidates of the same party, he who is most devoted to the Union, and most opposed to treason, can receive most of the people’s votes. It shows also, to the extent yet known, that we have more men now, than we had when the war began. Gold is good in its place, but living, brave, patriotic men are better than gold.

But the rebellion continues; and now that the election is over, may not all, having a common interest, re-unite in a common effort, to save our common country? For my own part I have striven, and shall strive, to avoid placing any obstacle in the way. So long as I have been here I have not willingly planted a thorn in any man’s bosom.

While I am deeply sensible to the high compliment of a re-election; and duly grateful, as I trust, to Almighty God for having directed my countrymen to a right conclusion, as I think, for their own good, it adds nothing to my satisfaction that any other man may be disappointed or pained by the result.

May I ask those who have not differed with me, to join with me, and in this same spirit towards those who have?

And now, let me close by asking three hearty cheers for our brave soldiers and seamen and their gallant and skilled commanders.

Abraham Lincoln

November 10, 1864