War seemed far away to the editors of a Maryland weekly newspaper–until the Battle of Antietam rocked their world

On September 17, 1862, a new edition of the Herald of Freedom and Torch Light of Hagerstown, Md., should have hit the streets, but it didn’t.

Nor had the weekly journal come out as scheduled on September 10. The Torch Light was a Union paper, and the mothers of its editors had raised no fools.

When Robert E. Lee crossed the Potomac into Maryland, the editors fled to Pennsylvania, where they stayed at a Chambersburg hotel until the coast was clear. They left behind the half-finished September 10 edition. When they returned after the bloody Battle of Antietam, everything in this agricultural valley in western Maryland had changed. But the editors resumed where they left off. They simply added new copy to existing, half-finished pages. The result, published September 24, was a bizarre compilation of pre-battle editorial bravado juxtaposed against shaky, post-battle prose penned by journalists utterly rattled.

This is the story of how the small-town press covered the Battle of Antietam. But it is also the story of how this Maryland community reacted to the coming of war. The news stories, features, advertisements, editorials, police briefs and public notices tell what locals—in a Union-leaning town in a border state—were doing and thinking before and after the battle. And as the September 10-24 edition of the newspaper clearly demonstrates, what they were doing and thinking before the battle would be quite different from what they would be doing and thinking afterward.

In the middle of September 1862, war tramped barefoot, dirty and disheveled into Washington County in western Maryland. It came in the form of Rebel soldiers whose clothes were muddy and mismatched, and who kept having to run off behind the bushes to flush the effects of unripe corn and green apples. For citizens of this rural county, the war seemed more of a traveling freak show than a threat. Most residents who made their living off the sticky clay soil of the Cumberland Valley knew only what they read in the papers, and the Hagerstown Herald of Freedom and Torch Light disdainfully wrote off the ragtag, hungry-eyed Southern band half marching, half straggling into town:

[T]heir cause is well nigh hopeless. Though determined to fight to the last, they cannot withstand during the coming winter the combined attacks of starvation, cold and our army; and then, if for no other reason, their cause must fail for want of inherent strength to sustain it.

The Confederates were also non-threatening for strategic reasons. General Lee, hoping to stir Marylanders to join their cause, had made it clear that soldiers were not to upset the locals. Crossing the Potomac, the Confederates portrayed themselves as liberators, urging residents to take up arms against the forces that had jailed their lawmakers and fought them in the streets of Baltimore. They didn’t know it, but they were in the wrong part of the state for that dog to hunt. Western Maryland was no hotbed of secession and never had been.

Maryland was historically and culturally a Southern state, but slavery was never terribly popular in Washington County. In 1820, 14 percent, or about 3,200 of its residents were enslaved, about half the state average and far below figures for states in the Deep South. By the time of the war, there were more free blacks in the county than slaves. The German Protestant religions of western Maryland tended to shun slavery, and some free black residents were more popular than the prowling slave catchers who itched to send them into bondage.

Slavery was legal, however, and people of Washington County abided by the law. Slave auctions were held in the Hagerstown Public Square. Runaway slaves were jailed. A notice in the Torch Light advised that the slaves (including a couple of children) of a Hampshire County, Va., family had been caught and thrown in the county clink; the rightful owners were urged to come and get ’em. This was ho-hum stuff—an adjoining notice urged readers to be on the lookout for a stray cow, black, with white feet. As with slaves, a “liberal reward” was promised for return of the wayward bovine.

When Lee first crossed into Maryland, he was nearly 40 miles southeast of Hagerstown; so the Torch Light editors didn’t lead with war news, but a memorable piece of fiction about a woman named Louise who is unhappily married to a man named Maurice who was supposed to be on the train to Glencove, but wasn’t, and it was a good thing too, because a bridge collapsed and “the mangled lie heaped together.” All this is too much for Louise, who, when she discovers Maurice is still alive, needs to be “restored” by a stiff belt at a roadside tavern, at which point she realizes, “to the singing of the birds of May,” that she still loves her husband after all.

Other Torch Light items included a report about a boa constrictor in an Ohio sideshow that went berserk and attacked his handler, who managed a “narrow escape” from a “horrible death.”

Whatever thoughts the people might have had about the war, states’ rights and slavery, the columns of the paper reflected the community’s more pressing concerns: arranging marriages, setting up households, selling merchandise, raising crops and making money.

They enjoyed as idyllic a lifestyle as any in America, as a Torch Light correspondent’s description of the region that became the Antietam battlefield attests:

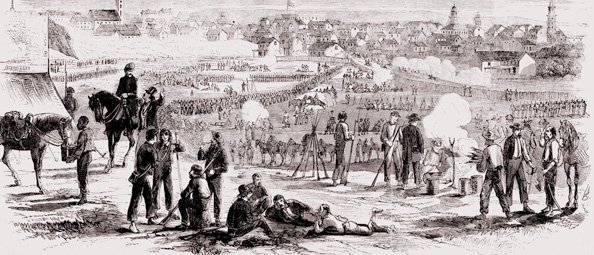

Numerous fine farmhouses dot the valley in every direction—some standing out plainly and boldly on the hilltops, others half-hidden down the little slopes; and, with the large comfortable barns about them, and their orchards of fruit trees, these hitherto happy and quiet homes greatly enrich the view, at least to the eyes of old campaigners. Nearly every part of the valley is under cultivation, and the scene is thus varied into squares of the light green of nearly ripened corn, the deeper green of clover, and the dull brown of newly ploughed fields. Toward the north, where our right lay, are some dense woods. Imagine this scene spread in the hollow of an amphitheatre of hills that rise in terraces around it, and you have the field of last Wednesday’s battle.

With harvest time coming, dealers were touting greatly improved reapers, hullers and thrashers in the pages of the Torch Light. On Franklin Street, Samuel Yeakle produced cane-seated chairs of mahogany and walnut. At a stand near the Lutheran church, Emanuel Levy hawked racks of newly arrived clothing, as well as bolts of tweed, linen and velvet. A pair of merchants had just returned from Baltimore with a wagon loaded with household goods such as clocks, mirrors, brooms, brushes, washboards, table settings and Japanese tinwear. M.H. Miller was unfortunate enough to sell something the Confederates had a real need of—shoes. Those under the weather could down a swig of Dr. Swayne’s Blood Purifying Panacea. For $10 a quarter, E.C. Bushnell would teach you to sing.

Some ads even played off a battlefield motif, like the one for Bombshell Hats. If they were amusing before September 17, the mirth wouldn’t last. Washington County, Md., was about to be brutally shaken to its limestone core.

Some ads even played off a battlefield motif, like the one for Bombshell Hats. If they were amusing before September 17, the mirth wouldn’t last. Washington County, Md., was about to be brutally shaken to its limestone core.

Citizens spent a few white-knuckled days watching Confederate columns pass by—and pass, and pass. It seemed there was no end to the wagon trains. Quartermasters hungry for goods of any type mobbed stores, only to find many merchants had already packed up and, like the newspaper editors, headed out of town. Some merchants stayed on, hoping all this unpleasantness might at least yield a profit. These hopes were dashed when the Confederates paid for their purchases in worthless Confederate scrip. Some saw the money as a metaphor for the men:

The condition and morale of the army is beyond description. They came among us not only badly clothed and unclean in person, but in a half-starving condition. For days, indeed, since the fights at Centreville, they have subsisted on rations of bread, irregularly issued, and green corn and fruits. Hundreds are weakened by diarrhea, and worn out by their long march, but they fight desperately because forced by hunger and want. Many express an ardent desire to lay down their arms, while on the other hand the officers and those better cared for are determined to fight to death rather than submit.

Locals hoped the intrusion would be brief, and indeed it was supposed to be. “Their conduct while among us,” the Torch Light grudgingly admitted, “was generally correct and considerate.” Pennsylvania was the target, and the Rebels saved their ire for the Keystone State.

Then a strange thing happened. The massive, northwestern-bound surge suddenly reversed itself and began oozing back. The locals didn’t understand. They had no way of knowing that a couple of Federal soldiers had lucked onto the “Lost Orders,” a scrawled outline of Lee’s entire battle plan found on the side of the road, and Union General George McClellan was ambling toward South Mountain with the intention of splitting the Army of Northern Virginia clean in two.

The returning Confederates held the Federals at bay at three mountain passes long enough for Lee to scramble back to some high ground near Sharpsburg on the west bank of a creek called Antietam. He arrived in time to confront a swelling sea of blue spilling down from the mountain heights.

In between these two streaming masses of men stood an unadorned white box of a building, a simple church consecrated to the prospects of peace. Nearby lived one of its founders, Samuel Mumma, whose thoughts in any given September would have been on the upcoming harvest. His neighbor, David Miller, might have been thinking about his promising crop of corn. They weren’t ready for what was about to happen. Nobody was.

To the casual Civil War student, the newspaper’s account of the ensuing conflict might be almost unrecognizable as the Battle of Antietam. The landmarks that have become historic icons—Bloody Lane, the Cornfield, Burnside Bridge—were, of course, not so-named at the time of the fight. Nor did the paper have the time or disposition to break down the day’s fight into separate elements as has been done since. The portrayal instead calls to mind two boxers rooted in the center of the ring, landing one big haymaker after another.

Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, I Corps commander, got the ball rolling, and before the sun could dry the dew, Miller’s precious cornfield, his life blood, was gone—as clean, Hooker later recalled, as if it had been cut with a knife. Things looked good for the Federals early, then the tide turned and all seemed lost; this would be the pattern for the day.

[T]he rebel forces gave way, though they certainly did not “skedaddle.” Slowly, and in very fair order, they fell back, disputing every foot they gave up with the greatest obstinacy. Still our boys pushed onward with magnificent courage and determination, every man, from Hooker down, intent only on victory. Occasionally a more determined resistance at some point in the line or some difficulty in the ground would check our advance for a few moments; but, with this exception, it was almost steady from its commencement until ten o’clock in the morning, when Gen. Hooker was wounded and carried from the field. General [James] Ricketts at once assumed command of the corps; but our victorious movement had lost its impulse….While our advance rather faltered, the rebels greatly reinforced made a sudden and impetuous onset, and drove our gallant fellows back over a portion of the hard won field. What we had won, however, was not relinquished without a desperate struggle, and here up the hills and down, through the woods and the standing corn, over the ploughed land and the clover, the line of fire swept to and fro as one side or the other gained a temporary advantage.

And so it went, back and forth all day, the thrill of victory shattering into the agony of defeat and then back, over and over again. Press coverage of the action at Antietam naturally benefited from the first-person experience of the writer, who is never identified, and reading the coverage, it’s almost possible to feel the reporter’s heartbeat pick up and settle back down with each turn of fortune. Here, there was no such thing as unbiased coverage. Our Northern reporter rooted and rooted hard for “our boys.” From his vantage point, he could describe the contrails of artillery shot crisscrossing the sky and forming a fishnet of smoke. “From every little hill a battery thundered until the mountains seemed to be shaken with the roar.”

Above the din he heard an unfamiliar rustling, a “stir and a murmur” that didn’t quite fit. Then he turned and saw it—Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin’s VI Corps coming into play after Hooker had lost his early gains. For once, the writer curtly noted, the reinforcements did not arrive too late or too exhausted from their march to join the fight. Once again, the spirits of our correspondent are lifted: “Two fresh divisions at such a time—what can they not achieve?” It helped that by this time the Southern boys had left everything they had on the field, and could hardly be expected to stand before a new column of blue. But a lesson had been learned.

It didn’t matter what the Confederate army looked like. It could fight like hell.

It is beyond all wonder how men such as the rebel troops are can fight as they do. That those ragged and filthy wretches, sick, hungry and in all ways miserable, should prove such heroes in fight, is past explanation. Men never fought better—There was one regiment that stood up before the fire of two or three of our long range batteries and of two regiments of infantry and though the air around them was vocal with the whistle of bullets and the scream of shells, there they stood and delivered their fire in perfect order, and there they continued to stand, until a battery of six light twelves was brought to bear on them and before that they broke.

Confident the situation to his right was in hand, the reporter turned his attention to his left, where General Ambrose Burnside was busy being Burnside. That is to say, the course of action alongside an arched, stone bridge over the Antietam Creek was not as purposeful as might have been hoped. The journalist was more polite than today’s models. “Whether anyone ‘blundered’ on the left is impossible for us to say.”

But there were clues. It was afternoon before Burnside could get his men across the creek, and once there he advanced until he found himself in a tight spot, raked by artillery. The day was saved, the writer assured his readers (perhaps too generously), when “word was passed along the hill for [Brig. Gen. George] Syke’s [sic] men to ‘fill in,’ and the tough old soldiers of the regular regiments, who had been lounging on the hill, quiet spectators of the battle, hurried gladly into line, joyful at the prospect that their turn had come and there they stood, ready to check the progress of any sudden disaster.”

If, as many experts believed, the battle had ended as a tactical draw, no one bothered to tell the Torch Light: “Let it be clearly understood that we were only entirely successful on the left—we suffered no disaster.” The way things had been going for the Federals in the Eastern Theater that summer, “suffering no disaster” might have seemed like a great victory. But the reporter did get carried away when he stated the enemy was “flying in the direction of Winchester,” and unlikely to stop until it hit Richmond.

But the flush of “victory” quickly wore off. The sun came up the next morning on an appalling scene. What was recognizable on Tuesday, by Thursday was not. The Torch Light tried to wrap its prose around the calamity, but even its own correspondents understood the impossibility of the task.

To one who has never seen a battle-field it is impossible to describe intelligently this, or, indeed, any one. Old landmarks are forgotten or effaced, distance loses itself in the mind of the spectator, and space is measured only by the results which its occupancy produces. Thus has it been here. Corn and stubble, pasture and fallow contribute their boundaries to the one great charnel house of the nation’s host, and on hill, in hollow, through field are strewn the bleeding, mangled bodies of dead and dying humanity.

The editors of the Herald of Freedom and Torch Light returned to their posts after the battle, and were mystified to find that while the Rebels had used the presses to print a few handbills, they had not destroyed the office. There was almost an element of disappointment that the Confederates had judged the newspaper to be of such low importance it wasn’t worth wrecking.

In this sense they might have been correct: Southern Washington County, Md., still physically existed, but the war seemed to have hollowed out its soul. Shock was too tame a word, horror too mild an emotion.

But few persons can form even the faintest conception of the horrors presented by a battle-field, the eye beholds but the lips can but faintly express the misery here exhibited — the soul is sickened, the heart grows faint. Here and there, in the ravaging course of the shells and shots may be seen the stalwart man, whose stout frame promised many years of natural existence, suddenly terminated by the death-dealing missile brought to bear upon our numerous and invincible hosts. The Union and the Rebel soldier, in many instances, lay close side by side, cold in death.

The paper described the region as mile after mile of triage. “From Hagerstown to the Southern limits of the county wounded and dying soldiers are to be found in every neighborhood and in nearly every house,” the papers reported. “The whole region of country between Boonsboro and Sharpsburg is one vast hospital. Houses and Barns are filled with them, and nearly the whole population is engaged in waiting on and ministering to their wants.” Men missing arms, legs or eyes waited for help. Sometimes it came, sometimes not. “The real horror can better be imagined than described, and a visit to the hospital where amputations are being made will fully impress the visitor with its startling horrors.”

The people of Sharpsburg, Boonsboro and Keedysville could either attend to the wounded or bury the dead that Rebels left on the field. They couldn’t do both. “Their dead were thickly strewn over every part of the field, and they left them for our men to bury. The number of dead was so great that up to Monday of this week many of them were still unburied, and the stench for miles around was almost intolerable.” Farmers such as Mumma and Miller looked out over what remained of their livelihood. For many, it had all vanished—crops, barns, homes, food. Winter was on the doorstep and what would there be to eat?

For some, the issue of food was more immediate. “The region of country between Sharpsburg and Boonsboro has been eaten out of food of every description. The two armies of from eighty to a hundred thousand each have swept over it, and devoured everything within reach. At Sharpsburg, we understand that the rebels sacked the town, and when they left many of the citizens had not a morsel of food to eat.”

Then came the hordes that descended on battlefields like flies on carrion—sightseers and photographers, tourists plucking grisly souvenirs, and heartbroken parents, searching for the faces of their boys. Carriages backed up for miles, as people far and wide came to see. Washington County never asked for the war, and it didn’t ask for these people either.

But the people of the county endured. The paper bucked them up. The first blood had been spilled in Baltimore; maybe it wasn’t too much to hope the last blood, this blood, would be spilled at Sharpsburg. It wouldn’t be, of course, and after witnessing the ferocity of the fight and the gumption of the enemy, the editors knew it.

But following the Battle of Antietam, they made their readers a promise: “We shall continue with unabated zeal to oppose [the South’s] unholy cause to the bitter end.”

Tim Rowland is a regular contributor to America’s Civil War and the author of the upcoming Quirky and Bizarre Stories of the Civil War (Skyhorse Publishing, 2011). See an interactive version of the newspaper at whilbr.org/HeraldofFreedom/index.aspx on the Western Maryland Historical Library Web site.