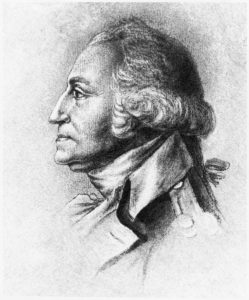

Despite intense suffering, the former president faced death with courage and strength of character

Several times, even when his days on battlefields were behind him, George Washington faced death. Shortly after his 1789 inauguration, a malignant or infected carbuncle on his left thigh threatened his life. The following year a case of pneumonia worsened enough to cause physicians and friends to despair. His response to Dr. Samuel Bard, who was treating him for pneumonia, was characteristic. “Do not flatter me with vain hopes,” Washington said. “I am not afraid to die, and therefore can hear the worst.”

Washington knew his family history all too well, and readily acknowledged “the impartial cruelty of time passing.” His father, Augustine, had died at 49; Augustine’s father, Lawrence, at 37. Both of George’s half-brothers had died early. None of his natural siblings had lived to 65. Surprisingly often as the General neared his three score and ten, he remarked in correspondence of days that “cannot be many;” of a thread “nearly spun.” His life was “hastening to an end,” he once wrote; he was “descending the hill; nearing the “bottom on the hill;” “approaching the shades below.” He had but a “short time” in this “theatre.” His “stream of life” was near its terminus. He spoke of his “few remaining years” and of a “remnant of a life journeying fast to the mansions of my ancestors.” He hoped to spend such time as remained “nearly worn” in agriculture “while I am spared (which in the course of things cannot be long).” He qualified comments about a coming year, appending “if I am alive” to them. He declined a wedding invitation because he was “going out of life.”

These repeated references mark the president not as pathologically morbid but as mordantly realistic. He embraced death’s inevitability. He had read the Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius, whose works he owned. “It is the duty of a thinking man to be neither superficial, nor impatient, nor yet contemptuous in his attitude towards death,” Aurelius writes, “But to await it as one of the operations of Nature which he will have to undergo.”

Believing that Providence, the term by which he usually referred to the deity, had chosen him for a special destiny, Washington similarly held that when death came, as it must, he would be “in the hands of a good providence.” Assessing his life, he could find evidence to support that notion: His ship docking safely after a stormy trip from Barbados, his surviving a danger-filled 1753 trip west to warn the French commander out of the Ohio Country, emerging unscathed from the French and Indian War despite being in the thick of fighting at Fort Necessity in 1754 and Braddock’s defeat in 1755. In near-miraculous Revolutionary War victories at Trenton (December 1776) and the subsequent Battle of Princeton (January 1777), he had been at one point only a stone’s throw from enemy muzzles, yet was untouched. He trusted in this “good Providence” for his future, which he believed included some vaguely defined afterlife—“the world of the spirits,” as he once called it. Upon the death of his sole surviving brother, Charles, in September 1799, Washington wrote, “I was the first, and am now the last, of my fathers Children by the second marriage who remain. When I shall be called upon to follow them, is known only to the giver of life. When the summons comes I shall endeavour to obey it with a good grace.”

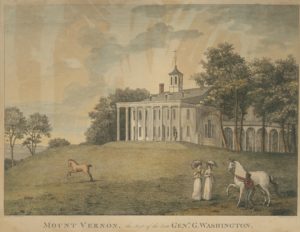

Death was not likely to have been on George Washington’s mind as he spent five cold, wet hours of Thursday, December 12, 1799, visiting his properties along the Potomac River. Lately his health had been robust, and he had busied himself making comprehensive plans for Mount Vernon in the coming century that he detailed in an exhaustive 19-page manuscript he had sent to his farm manager.

Returning to Mount Vernon from his expedition wet and chilled, hair and coat flecked with snow, he sat to dinner without changing clothes. “The weather was very disagreeable, a constant fall of rain, snow and hail with a high wind,” he wrote in his diary. He woke Friday morning to sleet, a sore throat, and what seemed to be the beginnings of a cold but again worked outside, this time marking trees he wished to have felled. Friday evening, he was very hoarse but in continuing good spirits as in he read aloud from a newspaper to his senior personal secretary, Tobias Lear. He voiced annoyance at Thomas Jefferson’s two top lieutenants, James Madison and James Monroe. In his diary, ever the record keeper, he made a note that closed with the datum “Mer[cury] 28 at night.” It would prove to be his final entry.

In the wee hours of Saturday morning, December 14, Washington woke feverish, struggling to breathe, and very uncomfortable. Wife Martha, herself recovering from a lingering illness, volunteered to go for help. Fearing the cold weather could bring on a relapse, her husband forbade her to leave the house.

Contrary to the popular scenario of a placid and easy passing—that “beautiful death” confected by Parson Weems and perpetuated by admirers, what ensued for George Washington was horrible.

The latest medical studies indicate that the first president died of acute bacterial epiglottitis. The epiglottis, a flap of cartilage covered by skin, automatically covers the trachea, or windpipe, while a person is swallowing—unless the epiglottis is swollen. Inflammation caused by burns from hot food, liquids, or an infection can enlarge the epiglottis enough to unseat the flap, causing saliva to drain into the lungs, or block the trachea. Either condition can so profoundly compromise breathing as to terrify a sufferer.

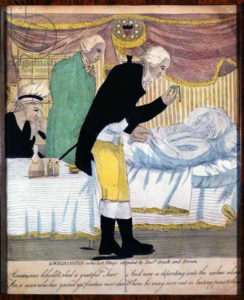

Breathing is a reflex that, impeded, can become a death sentence. George Washington experienced the terror of gasping for each breath. All day Saturday he was restless, constantly shifting position in his struggle for air. His household had summoned his physician and dear friend of over 40 years, Dr. James Craik, joined later by Dr. Gustavus Brown and Dr. Elijah Dick. These practitioners’ and his household attendants’ every action, even the simplest, compounded their patient’s suffering and perhaps hastened his demise. “A mixture of Molasses, Vinegar & butter was prepared to try its effects in the throat; but he could not swallow a drop,” Lear wrote. “Whenever he attempted it, he appeared to be distressed, convulsed and almost suffocated.”

Per the medical theory of the day, Washington’s doctors bled him four times, draining his depleted system of more than 80 ounces of blood. Besides severely weakening the General, bloodletting compromised his circulation. Patients with acute epiglottitis have difficulty inhaling, which induces hypoxia, in which not enough oxygen is supplied to blood when it circulates in the body. Washington’s very significant loss of blood further reduced oxygenation.

Dr. Dick proposed a radical step: a tracheotomy. Now a familiar procedure performed even by emergency medical technicians, the tracheotomy in 1799 rarely saw use in the United States even under the best of conditions, let alone in an emergency setting lacking proper technology. The method—essentially, puncturing the trachea to ease breathing—had been described in surgical detail only the year before. Dr. Dick would been working in low light on a conscious patient in extremis and shy five pints of blood. Optimally, Washington would have been flat on his back. However, that position could have caused his hugely enlarged epiglottis to flop, obstructing his trachea. Laudanum, an orally administered opiate, might have dulled his pain but also suppressed his respiration, perhaps fatally. No matter how skilled the surgeon, the thought of attempting a tracheotomy on an awake, semi-seated patient without local anesthesia was so daunting that it is no wonder that the other physicians rejected the idea.

Hoping to relieve their patient’s intense discomfort, the doctors repeatedly dosed him with purgatives emetic tartar and calomel. Vomiting and voiding the bowels, thought beneficial, actually compromised circulation while putting a patient through physical hell. Amid the bedroom’s reek the doctors applied cantharides—a caustic powder made from ground insects—to cause blistering, another supposed treatment with no alleviating effect.

Washington’s response to his final challenge offers a window into his character. He showed courage, diligence, sensitivity, and modesty, while instructing those at hand on important matters. One of his most endearing traits was his capacity to display in the same moment both power and diffidence, a blend achieved through self-effacement and relentless goodwill. “He was respectful to the meanest person whose salute he never failed to return,” a contemporary wrote. This characteristic showed in his concern for his wife’s welfare, even as he was fighting for every lungful of air. When his overseer, summoned to bleed him, shied at the thought of putting his employer under the knife, Washington was reassuring. “Don’t be afraid,” he told the man. Though in agony, Washington apologized for causing trouble. He worried that Lear, always poised to help him move in his search for air, would exhaust himself. The enslaved Christopher Sheels, his body servant, had been standing by Washington’s bed all day. He asked his man to sit. Sheels did as asked, his last act at Washington’s behest.

To the end, Washington maintained a relentless focus on key details such as his final will and testament, whose 29 pages he had composed that summer. Knowing this document would occasion public discussion, he included points intended for posterity, such as identifying himself in his will as “I George Washington, a citizen of the United States,” annealing himself in death to the union to which he had devoted much of his life.

And, in essentially his last gesture, his will freed his personal slaves (by law, he had no say about enslaved persons his wife and the Custis estate owned). In an indirect but strong statement to his countrymen, present and future, he provided for the education of the younger freed slaves and stipulated that those of his slaves who were too old to work and who were children without parents “be comfortably cloathed and fed by my heirs.” He particularly enjoined his executors “to see that this clause respecting Slaves, and every part thereof be religiously fulfilled. . .. without evasion, neglect or delay.”

Washington wanted his 1799 will enforced, not one written at the start of the Revolution. He asked Martha to go to his study and retrieve from his desk both wills. When she did, the General indicated which was the operative document and requested she burn the other, which she did.

Washington then spoke briefly, but at greater length than at any other time during his final crisis. Characteristically, he expressed concern for personal materials. “Arrange and record all my late military letters and papers,” he told Lear. “Arrange my accounts and settle my books, as you know more about them than anyone else, and let Mr. Rawlins [Albin Rawlins, the General’s secretary] finish recording my other letters which he has begun.”

Finality illuminated his self-discipline and devotion to duty—in this situation the duty to maintain fortitude and patience, embracing caregivers’ efforts to restore him, however unavailing he thought those efforts. Certainly, he needed all of his resources to bear his final painful ordeal. “I die hard,” he told Dr. Craik. “But I am not afraid to go.”

The microbial storm raged unabated, likely prolonged by whatever remained of his once-magnificent physique. As was common in that era, Washington feared being buried alive. After several unsuccessful efforts, he at last managed to communicate to Lear that he was not to be interred until his remains had lain still at least two days. Lear, overcome, simply nodded.

“Do you understand me?” Washington gasped.

Yes, Lear said.

“`Tis well.”

With that, lack of oxygen and a surfeit of carbon dioxide overwhelmed the general. As unconsciousness overcame him, George Washington closed his eyes. His hand, which he had had on his pulse, fell to his side. His countenance changed, and as Lear noted, he “expired without a struggle or a sigh.” He was 67.

Peter R. Henriques is Professor of History, Emeritus, at George Mason University and author of First and Always: A New Portrait of George Washington (2020) and Realistic Visionary: A Portrait of George Washington (2006).

This is an American History Magazine web-exclusive story. To subscribe to our magazine, click here.