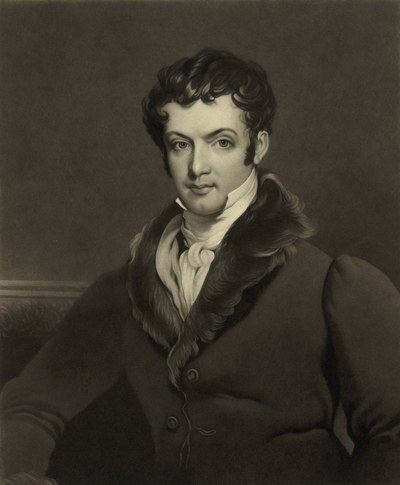

Washington Irving was America’s first author-celebrity—one moccasined step ahead of James Fenimore Cooper, who gained fame for his Leatherstocking Tales, featuring frontier rifleman Natty Bumppo, his Indian foster brother, Chingachgook, and foster nephew Uncas, the “last of the Mohicans.” By the time Cooper first forayed into the literary frontier in 1823, Irving had already introduced readers to the Hudson Valley Dutch in his short stories “Rip Van Winkle” (1819) and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1820). Those two comic ghost tales remain the most-read Irving works, as opposed, for example, to a five-volume biography of his namesake, George Washington, whom the author met when he was a child. But Irving, too, wrote about the frontier, based on firsthand observation. As in Cooper’s works, the Indians in Irving’s narrative were more noble than savage, and some of the frontier whites he described were very rough articles indeed.

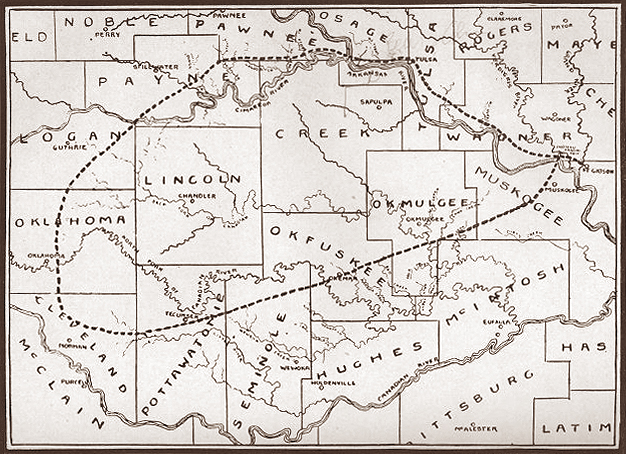

Irving’s introduction to the American frontier came in 1832 during a monthlong trek across what soon became Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). His adventure began that spring on a ship headed back to the United States from Europe. During the crossing Irving—who had kept up his writing while touring the Continent and later served as secretary to the American legation in London—met Charles Joseph Latrobe, a 31-year-old Englishman of French ancestry with “all the buoyancy and accommodating spirit of a native of the Continent,” and traveling companion Albert Alexander de Pourtalès, a 19-year-old Franco-Swiss count “full of talent and spirit, but galliard in the extreme and prone to every sort of wild adventure.” That summer the trio met up for a ramble through the White Mountains of New Hampshire, then set out from Buffalo on Lake Erie aboard a Detroit-bound steamer. While aboard they had a chance encounter with Judge Henry Leavitt Ellsworth of Connecticut, whom President Andrew Jackson had recently appointed to a board of commissioners arranging for the removal of the Southern Indian tribes west of the Mississippi. Irving described the judge as “a man in whom a course of legal practice and political life had not been able to vitiate an innate simplicity and benevolence of heart.” Ellsworth explained that he was headed into largely unexplored Indian country and asked Irving, Latrobe and Count Albert if they wanted to join him. They jumped at the chance.

Born into a merchant-class family in New York City, Irving spoke French and German and had spent two decades in the cultured cities of Europe. He was pushing 50 and more of a bon vivant than a frontiersman. But aside from some lumps and bumps he had the time of his life in Indian country. He kept a journal and ultimately wrote a book about the experience. First published in 1835, A Tour on the Prairies has never been out of print.

Commissioner Ellsworth and party disembarked at Ashtabula, Ohio, traveled southwest to Louisville, steamed down the Ohio to the Mississippi, then made their way upriver to St. Louis, arriving on September 13. There they met Indian Affairs Superintendent William Clark, famed co-commander of the 1804–06 Lewis and Clark Expedition and former governor of Missouri Territory. After agreeing to rendezvous in Independence, Mo., Ellsworth boarded a steamer headed up the Missouri while Irving, Latrobe and Count Albert set off cross-country. To help them tote supplies and set up camp, the trio retained “a little, swarthy, meager French creole named Antoine but familiarly dubbed Tonish.” In his narrative Irving assigned Tonish the role of comic Frenchman, a familiar literary figure of the era. “If all this little vagabond said of himself were to be believed, he was without morals, without caste, without creed, without country and even without language, for he spoke a jargon of English, French, and Osage.” Tonish apparently had a nose for class, however, as he promptly volunteered to squire the young count, “to teach him how to catch the wild horse, bring down the buffalo and win the smiles of Indian princesses.” At month’s end Ellsworth rejoined them in Independence, and the men set out south. They arrived at Fort Gibson, at the junction of the Arkansas and Neosho rivers, on October 8.

Ellsworth was as eager as his traveling companions to explore Indian country. He learned that three days earlier a party of 15 rangers had ridden out on a reconnaissance south to the Red River. Determined to join them, the commissioner arranged for a soldier escort and sent two Indian scouts to halt the rangers. Irving selected a “stout silver-gray” as a riding horse when the party set out from Fort Gibson on October 10. Packhorses toted their provisions—two weeks’ worth—and Tonish was assigned to drive the train. “He was in high glee, having experienced a kind of promotion,” Irving recalled. “Now he was master of the horse.”

As they forded the Verdigris River, Irving spotted on the far bank a rifle-toting Creek Indian on horseback wearing a blue shirt trimmed in scarlet and a colorful, turbanlike head covering. “[He] looked like a wild Arab on the prowl,” Irving noted. “Our loquacious and ever-meddling little Frenchman called out to him in his Babylonish jargon, but the savage, having satisfied his curiosity, tossed his head in the air, turned the head of his steed and, galloping along the shore, soon disappeared among the trees.”

At a trading post on the Verdigris the party caught up to the rangers. “They were a heterogeneous crew,” Irving wrote, “some in frock coats made of green blankets, others in leathern hunting shirts, but the most part in marvelously ill-cut garments, much the worse for wear and evidently out on for rugged service.” While there Irving met Sam Houston, future hero of Texas, then living with his Cherokee wife and family on the Neosho.

The author also got his first close look at the Indians:

[Near the rangers] was a group of Osages: stately fellows; stern and simple in garb and aspect. They wore no ornaments; their dress consisted merely of blankets, leggings and moccasins. Their heads were bare; their hair was cropped close, except a bristling ridge on the top, like the crest of a helmet, with a long scalp lock hanging behind. They had fine Roman countenances and broad, deep chests; and, as they generally wore their blankets wrapped round their loins, so as to leave the bust and arms bare, they looked like so many noble bronze figures.…

In contrast to these was a gaily dressed party of Creeks. There is something, at the first glance, quite oriental in the appearance of this tribe. They dress in calico hunting shirts of various brilliant colors, decorated with bright fringes and belted with broad girdles, embroidered with beads; they have leggings of dressed deerskins or of green or scarlet cloth, with embroidered knee-bands and tassels. Their moccasins are fancifully wrought and ornamented, and they wear gaudy handkerchiefs tastefully bound round their heads.

Seeking a dedicated hunter, Ellsworth and Irving hired Pierre Beatte, a muscular French-Osage half-blood in his mid-30s. “His features were not bad, being shaped not unlike those of Napoléon, but sharpened up with high Indian cheekbones,” Irving noted with romantic flair. “He had, however, a sullen, saturnine expression set off by a slouched woolen hat and elf locks that hung about his ears.” Beatte became the noble savage of the tale. Cooper had published The Last of the Mohicans six years earlier, and Irving, without fabrication, highlighted those aspects of the sturdy guide’s character in sincere emulation if not competition with Cooper.

And so the party set out with the comic Frenchman who was part Indian and the noble savage who was part French. The pair soon proved their worth at a ford on the Arkansas.

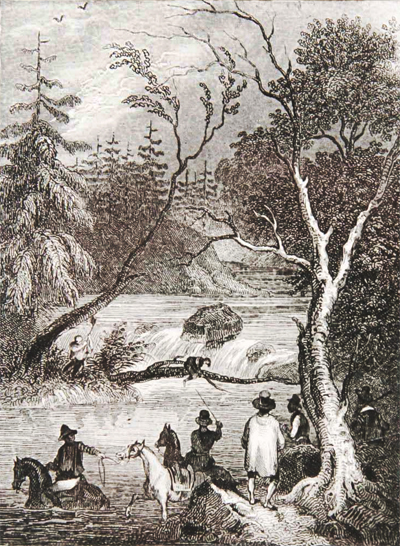

As the rangers felled trees to make rafts, Beatte and Tonish prepared another mode of transport. “They had procured a dried buffalo skin,” Irving recalled. “Cords were passed through a number of small eyelet holes with which it was bordered, and it was drawn up until it formed a kind of deep trough. Sticks were then placed athwart it on the inside to keep it in shape.” After loading the makeshift coracle with supplies, Beatte took the cord in his teeth and pulled while Tonish steadied the burden. Irving and Ellsworth were next to cross:

It was with a sensation half serious, half comic that I found myself thus afloat on the skin of a buffalo in the midst of a wild river, surrounded by wilderness and towed along by a half savage, whooping and yelling like a devil incarnate. To please the vanity of little Tonish, I discharged the double-barreled gun, to the right and left, when in the center of the stream. The report echoed along the woody shores and was answered by shouts from some of the rangers, to the great exultation of the little Frenchman, who took to himself the whole glory of this Indian mode of navigation.

‘It was with a sensation half serious, half comic that I found myself thus afloat on the skin of a buffalo in the midst of a wild river, surrounded by wilderness and towed along by a half savage, whooping and yelling like a devil incarnate’

Completing Irving’s cast of characters was Old Ryan, an experienced frontiersman bearing a remarkable likeness to Cooper’s Natty Bumppo. “He is as much at home in the woods or on a prairie as he would be in his own farmyard,” the ranger captain told Irving. “He’s never lost, wherever he is.” Old Ryan’s marksmanship, like Bumppo’s, is renowned, and like Cooper’s aging hero in The Pioneers, he deplores the senseless killing of animals and especially hates the practice of “bleating” deer—imitating the distress cries of fawns with homemade calls to lure does into easy rifle range. “I’ve been with hunters who had bleats and have made them throw them away,” the otherwise hardened frontiersman tells Irving. “It is a rascally trick to take advantage of a mother’s love for her young.”

That said, Old Ryan and the other hunters took a large number of deer and wild turkeys over the month the party spent in the wilds of Indian country. The outdoorsmen certainly didn’t stand on ceremony. “Bread” consisted of dough wrapped around a green stick and roasted over the campfire. While Irving despaired as their flour supply dwindled, Beatte merely grunted, “Bread is only fit for a child.” Wild honey was another matter. Finding a hollow tree packed with honey-filled combs, bee hunters among the party dipped into them with “the holiday appetite of a schoolboy.” In a literary reverie Irving noted that the honeybee was the emblem of approaching white settlers, as much as the buffalo was of the receding Indian.

Though Irving was admittedly “nothing of a sportsman,” he confessed a longstanding desire to hunt a buffalo on horseback. He ultimately got his wish, and a desperate hunt it turned out to be:

I singled out a buffalo and by a fortunate shot brought it down on the spot. The ball had struck a vital part; it could not move from the place where it fell but lay there struggling in mortal agony.…Now that the excitement was over, I could not but look with commiseration upon the poor animal that lay struggling and bleeding at my feet.…It became now an act of mercy to give him his quietus and put him out of his misery. I primed one of the pistols, therefore, and advanced close up to the buffalo. To inflict a wound thus in cold blood I found a totally different thing from firing in the heat of the chase.…The ball must have passed through the heart, for the animal gave one convulsive throe and expired.…I stood meditating and moralizing over the wreck I had so wantonly produced.

Irving found aspects of wild horse wrangling equally disturbing. On the gallop, rangers would slip a noose over a wild horse’s neck with a forked stick, in the manner of the Mongols, rather than with a thrown lariat in the manner of the Mexicans. Another trick they employed was to “crease” a horse with a rifle shot to the nape of its neck. A well-aimed ball would stun the animal long enough to secure it, while a miss might maim it or kill it outright. Though he kept it to himself, Irving was glad whenever a horse escaped.

Two weeks into their journey the party finally encountered Indians—seven Osage warriors, three armed with “indifferent fowling pieces,” the rest with bows and arrows. Recalling his duty, Commissioner Ellsworth “made a speech, exhorting them to abstain from all offensive acts against the Pawnees…[and] informing them of the plan of their father at Washington to put an end to all war among his red children.”

The warriors listened politely, spoke briefly among themselves and rode away.

“Fancying I saw a lurking smile in the countenance of our interpreter, Beatte,” Irving recalled, “I privately inquired what the Indians had said to each other.…The leader, he said, had observed to his companions that, as their great father intended so soon to put an end to all warfare, it behooved them to make use of the little time that was left them. So they departed, with redoubled zeal, to pursue their project of horse stealing!”

In his dual capacity as translator, Beatte also passed along to Irving an Indian romance of the type he so much admired. It centers on a young hunter, betrothed to an Osage maiden, who returns to camp after some weeks only to find it abandoned:

At a distance he beheld a female seated, as if weeping, by the side of the stream. It was his affianced bride.…

“What art thou doing here alone?”

“Waiting for thee.”

“Then let us hasten to join our people.…”

He gave her his pack to carry and walked ahead, according to the Indian custom.

They came to where the smoke of the distant camp was seen rising from the woody margin of the stream. The girl seated herself at the foot of a tree. “It is not proper for us to return together,” said she. “I will wait here.”

The young hunter proceeded to the camp alone and was received by his relations with gloomy countenances.

“What evil has happened,” said he, “that ye are all so sad?”

No one replied.

He turned to his favorite sister and bade her go forth, seek his bride and conduct her to the camp.

“Alas!” cried she. “How shall I seek her? She died a few days since.”

The relations of the young girl now surrounded him, weeping and wailing; but he refused to believe the dismal tidings. “But a few moments since,” cried he, “I left her alone and in health! Come with me, and I will conduct you to her.”

He led the way to the tree where she had seated herself, but she was no longer there, and his pack lay on the ground. The fatal truth struck him to the heart; he fell to the ground dead.

The credulous Osages believed the story. Even Beatte—raised Catholic, a sometime worker in a Protestant mission and a hellion on the warpath against the Pawnees—retained some of his Indian superstitions. On hearing the rangers would pass the site of a Pawnee massacre, the surgeon of the troop offered Beatte money for a skull. The latter was appalled—even though he had been in the Osage war party and participated in the killing. “No!” Beatte barked. “Dat too bad! I have heart strong enough—I no care kill. But let the dead alone!”

The expedition began thinking of home as the young rangers ran all the fat off their horses and exhausted their supplies, even the flour for dough on a stick. After a slog of a return march, during which the men were forced to abandon some horses and reduced to eating soup made of boiled turkey bones, they arrived at a settler’s cabin on the Arkansas River. Their hostess was a hefty black woman named Madam Bradley. Her white husband was away, but she happily fixed a banquet for the famished travelers. Irving’s gratitude was in proportion to his hunger:

I hailed her as some swart fairy of the wild that had suddenly conjured up a banquet in the desert.…Placing a brown earthen dish on the floor, she inclined the corpulent cauldron on one side, and out leaped sundry great morsels of beef, with a regiment of turnips tumbling after them and a rich cascade of broth overflowing the whole.…Head of Apicius, what a banquet!

Irving and companions arrived at Fort Gibson on November 9, and the author boarded a steamboat that evening, headed down the Arkansas and then the Mississippi to New Orleans. The book he distilled from his notes includes a sympathetic look at Osages and Creeks very much at variance with stereotypes expressed elsewhere—even in his own earlier writings or those of Cooper, in which Indians, heroic or savage, come off rather solemn.

The Indians that I have had an opportunity of seeing in real life are quite different from those described in poetry. They are by no means the stoics that they are represented—taciturn, unbending, without a tear or a smile. Taciturn they are, it is true, when in company with white men whose goodwill they distrust, and whose language they do not understand; but the white man is equally taciturn under like circumstances. When the Indians are among themselves, however, there cannot be greater gossips. Half their time is taken up in talking over their adventures in war and hunting and in telling whimsical stories. They are great mimics and buffoons, also, and entertain themselves excessively at the expense of the whites with whom they have associated and who have supposed them impressed with profound respect for their grandeur and dignity. They are curious observers, noting everything in silence, but with a keen and watchful eye, occasionally exchanging a glance or a grunt with each other, when anything particularly strikes them, but reserving all comments until they are alone. Then it is that they give full scope to criticism, satire, mimicry and mirth.

In 1835 Irving purchased a neglected riverfront house in Tarrytown, N.Y. Dubbed Sunnyside, it remained the author’s home through his death in 1859. Among the personal secretaries who worked for Irving at Sunnyside was Henry Beebe Carrington, who later served in the Civil War and seven years after the author’s death was assigned command of the Army’s forts along the Bozeman Trail at the outset of Red Cloud’s War. One wonders if he ever read A Tour on the Prairies. WW

John Koster wrote Custer Survivor (in its third edition) and Custer’s Lost Scout. For further reading he recommends A Tour on the Prairies, by Washington Irving; The Rambler in North America: 1832–1833, by Charles Joseph Latrobe; and Washington Irving on the Prairie, by Henry Leavitt Ellsworth.