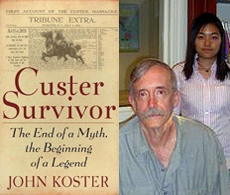

Army veteran and former newspaper journalist John Koster has never been one to back away from controversy. In 2010 his book Custer Survivor: The End of a Myth, the Beginning of a Legend (Chronology Books, $16.95) certainly stirred up a hornet’s nest among Little Bighorn scholars and George Armstrong Custer history buffs. A second edition was released before the year was out, but Koster wasn’t backing away from his central claim—namely that one 7th Cavalry trooper, C Company 2nd Sgt. Frank Finkel, escaped the massacre of Custer’s immediate command on June 25, 1876, and lived until 1930.

Finkel’s account first appeared in print in the 1920s, but most historians continue to dismiss him as a fraud, just as most discredit Brushy Bill Robert’s claims that he was Billy the Kid and J. Frank Dalton’s claim that he was Jesse James. Still, Koster insists Finkel was for real. Here he discusses the controversy and Frank Finkel..

‘That there could actually be a Custer survivor is the sort of story no newsman could possibly pass up’

What drew you to Frank Finkel’s claim?

That there could actually be a Custer survivor is the sort of story no newsman could possibly pass up. I wondered if there might have been a real Custer survivor. I knew there had been somewhere between 70 and 200 fakes, and I also knew the evidence had to be stronger than some bogus deathbed confession or thirdhand Indian legend. I’d done a lot of forensic-style investigations in my 40-odd years as a newspaperman, and I kept on a constant watch for anything that could suggest a genuine Custer survivor. Rain-in-the-Face had told a writer named Kent Thomas around 1894 that “one long sword got away” —mila hanska in Lakota means “long knife,” a cavalryman — but Thomas didn’t press him for details at the time.

Did you have a preconceived notion before you began your research?

When I first read Lieutenant Edward Godfrey’s 1892 Century account of the Little Bighorn and its aftermath as printed in The Custer Myth by Colonel W.A. Graham, Godfrey describing finding a dead 7th Cavalry horse at the confluence of the Rosebud and Yellowstone rivers in August 1876. The horse had been shot in the head and was found with a carbine and all the horse trappings except the bridle. Godfrey, who had of course fought at the battle under [Major Marcus] Reno and [Captain Frederick] Benteen, said this was the one chance he knew of to locate an actual survivor, but no one had mentioned the dead horse as far as he knew in 1892 when he wrote the article. More than a century later one of my researchers was trawling through the internet and came up with a letter from Hermie Finkel Billmeyer, Finkel’s widow, in which she said her husband was a survivor, has served in Company C and had ridden a roan. A.E. Brininstool had received an amended letter from Godfrey, written around 1923, in which Godfrey said the dead horse was a sorrel. A roan and a sorrel are both reddish horses with light manes, and of the five companies destroyed under Custer’s command, only C Company—the company Finkel insisted he came from—had ridden sorrel horses. So we have a guy claiming (through his second wife) that he was at the Little Bighorn, claiming he rode a horse of the right color for C Company. I got on the trail.

Custer biographer Jeffry Wert says you make a “solid claim,” but others dismiss Finkel’s account. Why is that?

I think they’re locked into mythology that won’t permit a survivor to exist. The Little Bighorn is famous mostly because it was a big defeat with—supposedly—no survivors. In St. Clair’s defeat by the tribes of the Northwest Territory twice as many soldiers were killed as at the Little Bighorn, but because half of the soldiers escaped, people had sort of dropped it down the memory hole. The Little Bighorn was called “an American Thermopylae”—but it wasn’t. A lot of soldiers tried to escape, and some were found miles from the actual killing ground. Nobody talks about them much, but they existed. So did Frank Finkel.

Is it possible to change a view that has been accepted for 135 years?

You can’t change a lot of people’s beliefs. The other night a very nice old man who wasn’t there gave a talk about the attack on Pearl Harbor and showed that famous photograph of the riddled car with dead civilians inside as evidence of the deliberate strafing of civilians. But the relatives of the dead men in the car saw them killed by an American anti-aircraft shell that missed a target and struck the road and said so. People in Hawaii have known the whole story of years, but we still see the riddled car used as an example of the strafing of civilians. A 90-year-old man who was actually at Pearl Harbor blew the lecturer’s doors off and told him that Franklin Delano Roosevelt knew it was coming, that the whole thing was a set-up that killed a lot of Americans without giving them a fair chance to fight back. That’s the difference between real history and patriotic mythology. Similarly, people who want to believe in a “Sioux ambush” by bloodthirsty savages don’t want there to be survivors—but every serious student of the battle knows that Custer attacked a sleeping village and achieved complete surprise when the battle first started.

Many soldiers’ bodies were mutilated. Charles Windolph said he couldn’t identify Finkel’s body. Daniel Kanipe said he found the body. Explain the discrepancy and why you believe Kanipe was mistaken.

Kanipe was a good soldier in 1876, but when he gave that interview in the 1920s, he was an old man in his 70s with a year left to live. Kanipe also remembered seeing 75 dead Indians in two burial teepees when the Indians actually lost 36 people, including 10 women and children. He remembered Custer turning down a chance to take a breech-loading Rodman cannon—most experts say Custer only turned down Gatling guns, not a cannon, which could have made quite a difference. He saw Custer’s body and said Custer was shot once. Everybody else, without exception, said Custer was shot twice. Kanipe also said Sergeant Edwin Bobo’s body hadn’t been mutilated at all—but since he married Sergeant Bobo’s widow and helped her raise Bobo’s kids, along with their own, I’d prefer to see him as a man of compassion and chivalry and not call him a liar. He meant well in shielding his wife. Nobody else said Bobo hadn’t been mutilated. Kanipe in his 20s was a good steady soldier—in his 70s he was either telling people what they wanted to hear or memory was playing tricks. Windolph suffered in his own memory for the rest of his life because he hadn’t been able to give his best friend a Christian burial. He was still telling his daughter about it in the 1940s. Windolph was the one who really tried to find that body.

Finkel was wounded. Why didn’t he return to the army after he had recovered from his wounds?

I think Finkel may have thought he’d done enough for his $22.50 a month after the Little Bighorn. Desertion was endemic in the frontier Army, and since everybody thought he was dead, he had a great shot at it.

Remember, like Windolph, William O. Taylor and many of the officers, Finkel didn’t hate Indians. He first wife was part Cherokee, and he probably made a pretty good marriage for a drifter, because a lot of people in those days were leery of marrying people with “Injun blood.”

Then, at best he was AWOL. At worst, he was a deserter. And somewhere down the line, his name is changed. Yet when he makes his claims to friends and gives talks, locally at least his story is accepted? Why didn’t it get bigger play, or did it?

Finkel arrived in Dayton, Wash., signing is name as “Finckle”—the spelling on the enlistment form. The 7th Cavalry had him down as “Finkle,” which is the same way he spelled his name until about the turn of the 20th century, when it turned to “Finkel”—yet we know he was the same person based on marriage and land transactions. People who knew him around Dayton remembered him as honest, somewhat reticent and not a windbag or a blowhard. Older people I’ve talked to remember their grandparents saying that you could take his word on anything. Why would a man who owned a square mile of farmland and three houses make up a cock-and-bull story about Custer’s Last Stand? He didn’t care about fame, and he didn’t need money. Most of the other so-called Custer survivors were drunks or, later on, showmen. Their motives were pretty obvious—a few free drinks or a real crowd-pleaser for their act.

Why did Finkel wait some 40 years before making his claim?

Finkel appears to have told a couple people around Dayton that he had been at the Little Bighorn and that it was nothing like what they had been told it was like, but he didn’t go public until a horseshoe game in 1920, when he appears to have told off a couple of loudmouths. He wasn’t eager for the notoriety. I suspect he just blew his stack hearing so much ignorance passed off as truth.

What was Finkel’s life like after 1876?

Mostly hard work and thrift. He bought and sometime sold farms and worked part-time as a carpenter. He got married in 1886 to Delia Rainwater, whose father was a prominent early settler in Dayton. Finkel and his first wife had five kids and lost two of them, but the other three grew up to marry and, in two cases, to have kids of their own. There are a lot of Finkel relatives around who grew up hearing themselves called liars when they, in their turn, tried to explain that there actually had been a survivor of Custer’s Last Stand. I didn’t talk to any of them until the book was just about finished, but they helped me out with a number of family photographs and some corrections for the second edition, none of which change the fact that Finkel was telling the truth.

Talk about the roles Chris Madsen and Dr. Charles Kuhlman played in the Finkel account.

Chris Madsen tried to pick the Finkel story apart when he heard about it after Finkel died, but he made a lot of mistakes. Madsen said all the Indians agreed there was no survivor, but he was wrong. Rain-in-the-Face said there was definitely a survivor and that he saw the man in Chicago, a city Finkel is known to have visited. Kuhlman said Finkel’s escape route and knowledge of the battle showed a knowledge of the topography only a real survivor would have known about. He sort of went off the road when he believed that Finkel had actually served as “Frank Hall”—a deserter who went over the hill a year before the 7th Cavalry left for the Sioux War of 1876. Finkel himself may have used that name once to a reporter, or the first wife may have used it when she was afraid he could be arrested for deserter. It’s a matter of record, however, that he told other reporters and his own family that he had served under the name “Finckle.” The second wife muddied the waters terribly, because she must have seen that he gave “Berlin, Prussia” as his birthplace and wanted to distance herself against the tidal wave of anti-German prejudice [during] World War I and the Hitler era. Finkel was actually born in Ohio to German parents who came from Bavaria. The “Prussian” thing was a chance to cash in on the fact that all things Prussian were the rage right after the Franco-Prussian War. Ever see those formal photographs of 7th Cavalry soldiers with spiked helmets? That’s where they got the idea. And that’s where Bismarck got its name—after the chancellor not the battleship.

What do we owe to Finkel’s second wife? And did she hurt or help his claim?

Finkel’s wife kept the claim alive, but by insisting he had actually served under the name “Frank Hall,” she also put some serious tangles in the trail. I personally owe her a lot. If she’d just fessed up and said, “Yes, he told people he was a Prussian, but he was born in Ohio,” somebody else would have clinched the story long before I did.

And if anybody had bothered to check the handwriting on the enlistment form against the signatures on Delia Rainwater Finkel’s probate and had realized they were in the same handwriting, I would have been obviated. Hermie Finkel Billmeyer kept denying over and over that Frank was the “Sergeant Finkle” on the 7th Cavalry roster and the Bismarck Tribune obituary. Obviously, handwritten signatures and height and hair/eye color comparisons more than suggest Finkel was Finkle.

What could Finkel have told us about the Little Bighorn that historians don’t know?

Finkel’s brief description of the Little Bighorn wasn’t what the American public believed in 1920. We have a vignette of him coming out of the Dreamland Theater in Dayton a few years before he went public and telling friend Robert Johnson, “That’s not the way it was at all.” His terse description sounds like what Richard Allen Fox and Doug Scott found in the 1980s—Custer’s five companies were inundated by massive gunfire from repeating rifles and shot to pieces. In a sense, that puts a better face on the fact that a lot of people broke and ran, either outside the perimeter or to the Deep Ravine. They never had a chance against that kind of firepower, and they must have realized it. The Indians themselves were astounded at what they were able to do with all those repeating rifles. When Lame White Man of the Cheyenne shouted out, “Come on! Now we can kill them all!” I don’t think he was as much bloodthirsty as he was amazed.

Explain how Finkel’s signatures prove his story was true.

Finkel’s multiple signatures are just the clincher to a story with a few other facts in his favor: He was known as an honest man. He didn’t want or need notoriety. Comparison of Sergeant Finckle of the 7th Cavalry and farmer Finkel of Dayton indicates he was the same man—6-feet-plus and actually over the height limit for the cavalry, dark hair and pale eyes, an unusual combination, and able to converse both in English and in German. How could farmer Frank Finkel of Dayton have picked a name off the front-page obituary in the Bismarck Tribune and guessed that “Sergeant Finkle” of C Company would be over 6 feet tall and bilingual? Did he really know what color horses C Company rode? Did he know about the massive Indian gunfire—most popular accounts of his time had the Indians using bows and arrows. The handwriting was just the climax of the search. At that point the agnostics’ cracker barrel was closed, and denial became implausible.

On the other hand, naysayers in a court of law would likely come up with handwriting experts who say the signatures aren’t by the same man or hand. How and why do you accept those experts you include in your book?

One of the experts was a psychiatrist with the U.S. Air Force and the prison system and also the author of about 30 books about the Civil War and the frontier. All his sources were handwritten, and he understood forensics. John Ydo studied handwriting at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and with the FBI. Keith Killion was a police detective for 25 years and is now the mayor of Ridgewood, N.J. These guys independently calculated things like the angle of slant and the “arachnographia”—spider writing—when Finkel got older and concluded the signatures were written by the same man, the first pair when he was young in 1872 and the second pair when he was old in 1921. The dying man’s signature from 1930 is also in the same handwriting, and so is a lead-pencil scribble on a postcard from 1914.

A talented forger could have possibly faked the old man’s handwriting from the signatures on the enlistment form—but why? Sergeant Finkle of the 7th Cavalry wasn’t exactly the Lost Dauphin of France or the Grand Duchess Anastasia. There were no crown jewels or hidden bank accounts at stake here. This is a guy who blurted out that he was at Custer’s Last Stand at a rustic horseshoe game. He wasn’t working a scam to inherit Sergeant Finkle’s lost millions, and with $40,000 in the bank, three houses, a prosperous family and a square mile of farmland, he didn’t need anybody to buy him a drink as a Custer survivor. You get the feeling reading the sparse newspaper accounts that he was sorry he’d ever said anything.

Finkel wasn’t the only white man to claim he’d survived the Little Bighorn. What about the others?

You know, it’s not impossible that a few other guys could have ridden through the Indians and just kept going. Nathan Short appears to have made it about 25 miles before his horse fell on him. The Crows found a lot of bodies, and nobody seems to have gone out to look. But the stories that the other survivor claimants told were all pretty ridiculous. A guy named Ridgely told people that Sitting Bull was a half-breed who spoke French and that five troopers, including an old man with a white beard, had been burned alive while Ridgely was prisoner in Sitting Bull’s camp. It turns out that Ridgely had been cutting hay in another part of Montana when the battle took place, and he had a reputation for making things up. Madsen encountered a broken-down old prospector who told him stories about being married to an Indian princess and seeing Custer’s body floating down the river—this guy wanted to get into the Old Soldier’s Home where Madsen was the director. You’ve also got desperado windbags writing preposterous letters to Elizabeth Custer, who had some money. Small-town people are good at spotting phonies, and they knew Frank Finkel was the real goods.

Getting away from Finkel. George Custer: Hero, fool or somewhere in between?

Custer is the most fascinating American figure of his era, because he was such a kaleidoscope of contradictions. He was probably the greatest cavalry officer of the Civil War, not only because of his daring, but also because of his instinct for tactics. He was highly intelligent—he could read French and Spanish, was adept in Indian sign language and was a fine writer with a wonderful sense of the ridiculous. Who else would admit to shooting his own horse by accident while hunting buffalo? He didn’t smoke, he didn’t curse much, and he was habitually sober. On the other hand, he adored his wife, but he was a scoundrel of a husband—and not just with Monahsetah—and he got involved in some very shady business deals. Custer was a poor boy married to a rich girl he could barely support and sometimes cheated on. He liked to take chances. He almost got taken off the case in the Sioux War of 1876 because he testified about the massive corruption in the War Department and the Indian Department—his testimony, incidentally, was very effective—and I think at the Little Bighorn he knew he’d have to pull off a triumph or face an obscure end to a glorious career. His blunder was, quite simply, that he didn’t realize that the Lakota and Cheyenne warriors were sleeping off an all-night dance and that instead of rounding up women and children he was trying to surround a force maybe twice the size of his own and with better weapons. He surprised them, but then they surprised him and shot his command to pieces. He probably died with great courage, but if he had been a consistent man of conscience, he wouldn’t have been there. The Indians had been lied to and swindled for decades, and they were brave men and boys defending their families. They were the real heroes of the Little Bighorn.

Why are people still fascinated with what happened at the Little Bighorn?

I think because the “no survivor” myth allows for endless speculation and endless argumentation—and because, when you come right down to it, Custer himself is such a fascinating study in contrasts.

What’s next for you?

I’m a mildly crippled U.S. Army veteran with a honorable discharge and a couple of miniscule medals, none of them for personally strangling Ho Chi Minh. But I had six relatives in World War II, one of them killed in a B-17 over Germany, another on the third ship into Tokyo Bay in 1945. In short, I have a detached perspective. I think I know what actually happened at Pearl Harbor, why the Japanese, who are not known to be stupid, attacked a country they couldn’t possibly defeat, and why nobody warned the Pacific Fleet or the Luzon Army and Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines or the Marines on Wake and Guam in time to head off a catastrophe that was a hundred times bloodier than the Little Bighorn and equally unnecessary. The Army bought 2,000 copies of the Cassilly Adams painting of Custer’s Last Stand and hung them up in mess halls to show the guys how to die fighting “savages” —or maybe to keep the food bills down. There were plenty of heroes in this one too, but I think people will be astounded to find out who the real villains were. Slight hint—some of the relevant translations, never before available in English, are from Russian as well as Japanese and Korean. My spies will not be revealed.