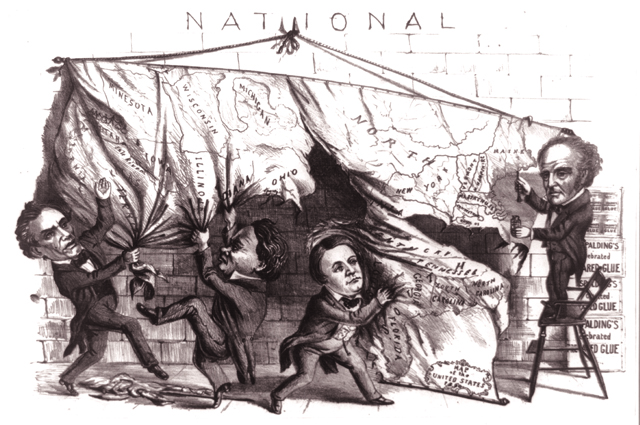

Southerners insisted they could legally bolt from the Union.

Northerners swore they could not.

War would settle the matter for good.

Over the centuries, various excuses have been employed for starting wars. Wars have been fought over land or honor. Wars have been fought over soccer (in the case of the conflict between Honduras and El Salvador in 1969) or even the shooting of a pig (in the case of the fighting between the United States and Britain in the San Juan Islands in 1859).

But the Civil War was largely fought over equally compelling interpretations of the U.S. Constitution. Which side was the Constitution on? That’s difficult to say.

The interpretative debate—and ultimately the war—turned on the intent of the framers of the Constitution and the meaning of a single word: sovereignty—which does not actually appear anywhere in the text of the Constitution.

Southern leaders like John C. Calhoun and Jefferson Davis argued that the Constitution was essentially a contract between sovereign states—with the contracting parties retaining the inherent authority to withdraw from the agreement. Northern leaders like Abraham Lincoln insisted the Constitution was neither a contract nor an agreement between sovereign states. It was an agreement with the people, and once a state enters the Union, it cannot leave the Union.

It is a touchstone of American constitutional law that this is a nation based on federalism—the union of states, which retain all rights not expressly given to the federal government. After the Declaration of Independence, when most people still identified themselves not as Americans but as Virginians, New Yorkers or Rhode Islanders, this union of “Free and Independent States” was defined as a “confederation.” Some framers of the Constitution, like Maryland’s Luther Martin, argued the new states were “separate sovereignties.” Others, like Pennsylvania’s James Wilson, took the opposite view that the states “were independent, not Individually but Unitedly.”

Supporting the individual sovereignty claims is the fierce independence that was asserted by states under the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, which actually established the name “The United States of America.” The charter, however, was careful to maintain the inherent sovereignty of its composite state elements, mandating that “each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated.” It affirmed the sovereignty of the respective states by declaring, “The said states hereby severally enter into a firm league of friendship with each other for their common defence [sic].” There would seem little question that the states agreed to the Confederation on the express recognition of their sovereignty and relative independence.

Supporting the later view of Lincoln, the perpetuality of the Union was referenced during the Confederation period. For example, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 stated that “the said territory, and the States which may be formed therein, shall forever remain a part of this confederacy of the United States of America.”

The Confederation produced endless conflicts as various states issued their own money, resisted national obligations and favored their own citizens in disputes. James Madison criticized the Articles of Confederation as reinforcing the view of the Union as “a league of sovereign powers, not as a political Constitution by virtue of which they are become one sovereign power.” Madison warned that such a view could lead to the “dissolving of the United States altogether.” If the matter had ended there with the Articles of Confederation, Lincoln would have had a much weaker case for the court of law in taking up arms to preserve the Union. His legal case was saved by an 18th-century bait-and-switch.

A convention was called in 1787 to amend the Articles of Confederation, but several delegates eventually concluded that a new political structure—a federation—was needed. As they debated what would become the Constitution, the status of the states was a primary concern. George Washington, who presided over the convention, noted, “It is obviously impracticable in the federal government of these states, to secure all rights of independent sovereignty to each, and yet provide for the interest and safety of all.” Of course, Washington was more concerned with a working federal government—and national army—than resolving the question of a state’s inherent right to withdraw from such a union. The new government forged in Philadelphia would have clear lines of authority for the federal system. The premise of the Constitution, however, was that states would still hold all rights not expressly given to the federal government.

The final version of the Constitution never actually refers to the states as “sovereign,” which for many at the time was the ultimate legal game-changer. In the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark 1819 decision in McCulloch v. Maryland, Chief Justice John Marshall espoused the view later embraced by Lincoln: “The government of the Union…is emphatically and truly, a government of the people.” Those with differing views resolved to leave the matter unresolved—and thereby planted the seed that would grow into a full civil war. But did Lincoln win by force of arms or force of argument?

On January 21, 1861, Jefferson Davis of Mississippi went to the well of the U.S. Senate one last time to announce that he had “satisfactory evidence that the State of Mississippi, by a solemn ordinance of her people in convention assembled, has declared her separation from the United States.” Before resigning his Senate seat, Davis laid out the basis for Mississippi’s legal claim, coming down squarely on the fact that in the Declaration of Independence “the communities were declaring their independence”—not “the people.” He added, “I have for many years advocated, as an essential attribute of state sovereignty, the right of a state to secede from the Union.”

Davis’ position reaffirmed that of John C. Calhoun, the powerful South Carolina senator who had long viewed the states as independent sovereign entities. In an 1833 speech upholding the right of his home state to nullify federal tariffs it believed were unfair, Calhoun insisted, “I go on the ground that [the] constitution was made by the States; that it is a federal union of the States, in which the several States still retain their sovereignty.” Calhoun allowed that a state could be barred from secession by a vote of two-thirds of the states under Article V, which lays out the procedure for amending the Constitution.

Davis’ position reaffirmed that of John C. Calhoun, the powerful South Carolina senator who had long viewed the states as independent sovereign entities. In an 1833 speech upholding the right of his home state to nullify federal tariffs it believed were unfair, Calhoun insisted, “I go on the ground that [the] constitution was made by the States; that it is a federal union of the States, in which the several States still retain their sovereignty.” Calhoun allowed that a state could be barred from secession by a vote of two-thirds of the states under Article V, which lays out the procedure for amending the Constitution.

Lincoln’s inauguration on March 4, 1861, was one of the least auspicious beginnings for any president in history. His election was used as a rallying cry for secession, and he became the head of a country that was falling apart even as he raised his hand to take the oath of office. His first inaugural address left no doubt about his legal position: “No State, upon its own mere motion, can lawfully get out of the Union, that resolves and ordinances to that effect are legally void, and that acts of violence, within any State or States, against the authority of the United States, are insurrectionary or revolutionary, according to circumstances.”

While Lincoln expressly called for a peaceful resolution, this was the final straw for many in the South who saw the speech as a veiled threat. Clearly when Lincoln took the oath to “preserve, protect, and defend” the Constitution, he considered himself bound to preserve the Union as the physical creation of the Declaration of Independence and a central subject of the Constitution. This was made plain in his next major legal argument—an address where Lincoln rejected the notion of sovereignty for states as an “ingenious sophism” that would lead “to the complete destruction of the Union.” In a Fourth of July message to a special session of Congress in 1861, Lincoln declared, “Our States have neither more, nor less power, than that reserved to them, in the Union, by the Constitution—no one of them ever having been a State out of the Union. The original ones passed into the Union even before they cast off their British colonial dependence; and the new ones each came into the Union directly from a condition of dependence, excepting Texas. And even Texas, in its temporary independence, was never designated a State.”

It is a brilliant framing of the issue, which Lincoln proceeds to characterize as nothing less than an attack on the very notion of democracy:

Our popular government has often been called an experiment. Two points in it, our people have already settled—the successful establishing, and the successful administering of it. One still remains—its successful maintenance against a formidable [internal] attempt to overthrow it. It is now for them to demonstrate to the world, that those who can fairly carry an election, can also suppress a rebellion—that ballots are the rightful, and peaceful, successors of bullets; and that when ballots have fairly, and constitutionally, decided, there can be no successful appeal, back to bullets; that there can be no successful appeal, except to ballots themselves, at succeeding elections. Such will be a great lesson of peace; teaching men that what they cannot take by an election, neither can they take it by a war—teaching all, the folly of being the beginners of a war.

Lincoln implicitly rejected the view of his predecessor, James Buchanan. Buchanan agreed that secession was not allowed under the Constitution, but he also believed the national government could not use force to keep a state in the Union. Notably, however, it was Buchanan who sent troops to protect Fort Sumter six days after South Carolina seceded. The subsequent seizure of Fort Sumter by rebels would push Lincoln on April 14, 1861, to call for 75,000 volunteers to restore the Southern states to the Union—a decisive move to war.

Lincoln showed his gift as a litigator in the July 4th address, though it should be noted that his scruples did not stop him from clearly violating the Constitution when he suspended habeas corpus in 1861 and 1862. His argument also rejects the suggestion of people like Calhoun that, if states can change the Constitution under Article V by democratic vote, they can agree to a state leaving the Union. Lincoln’s view is absolute and treats secession as nothing more than rebellion. Ironically, as Lincoln himself acknowledged, that places the states in the same position as the Constitution’s framers (and presumably himself as King George).

But he did note one telling difference: “Our adversaries have adopted some Declarations of Independence; in which, unlike the good old one, penned by Jefferson, they omit the words ‘all men are created equal.’”

Lincoln’s argument was more convincing, but only up to a point. The South did in fact secede because it was unwilling to accept decisions by a majority in Congress. Moreover, the critical passage of the Constitution may be more important than the status of the states when independence was declared. Davis and Calhoun’s argument was more compelling under the Articles of Confederation, where there was no express waiver of withdrawal. The reference to the “perpetuity” of the Union in the Articles and such documents as the Northwest Ordinance does not necessarily mean each state is bound in perpetuity, but that the nation itself is so created.

Lincoln’s argument was more convincing, but only up to a point. The South did in fact secede because it was unwilling to accept decisions by a majority in Congress. Moreover, the critical passage of the Constitution may be more important than the status of the states when independence was declared. Davis and Calhoun’s argument was more compelling under the Articles of Confederation, where there was no express waiver of withdrawal. The reference to the “perpetuity” of the Union in the Articles and such documents as the Northwest Ordinance does not necessarily mean each state is bound in perpetuity, but that the nation itself is so created.

After the Constitution was ratified, a new government was formed by the consent of the states that clearly established a single national government. While, as Lincoln noted, the states possessed powers not expressly given to the federal government, the federal government had sole power over the defense of its territory and maintenance of the Union. Citizens under the Constitution were guaranteed free travel and interstate commerce. Therefore it is in conflict to suggest that citizens could find themselves separated from the country as a whole by a seceding state.

Moreover, while neither the Declaration of Independence nor the Constitution says states can not secede, they also do not guarantee states such a right nor refer to the states as sovereign entities. While Calhoun’s argument that Article V allows for changing the Constitution is attractive on some levels, Article V is designed to amend the Constitution, not the Union. A clearly better argument could be made for a duly enacted amendment to the Constitution that would allow secession. In such a case, Lincoln would clearly have been warring against the democratic process he claimed to defend.

Neither side, in my view, had an overwhelming argument. Lincoln’s position was the one most likely to be upheld by an objective court of law. Faced with ambiguous founding and constitutional documents, the spirit of the language clearly supported the view that the original states formed a union and did not retain the sovereign authority to secede from that union.

Of course, a rebellion is ultimately a contest of arms rather than arguments, and to the victor goes the argument. This legal dispute would be resolved not by lawyers but by more practical men such as William Tecumseh Sherman and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson.

Ultimately, the War Between the States resolved the Constitution’s meaning for any states that entered the Union after 1865, with no delusions about the contractual understanding of the parties. Thus, 15 states from Alaska to Colorado to Washington entered in the full understanding that this was the view of the Union. Moreover, the enactment of the 14th Amendment strengthened the view that the Constitution is a compact between “the people” and the federal government. The amendment affirms the power of the states to make their own laws, but those laws cannot “abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

Ultimately, the War Between the States resolved the Constitution’s meaning for any states that entered the Union after 1865, with no delusions about the contractual understanding of the parties. Thus, 15 states from Alaska to Colorado to Washington entered in the full understanding that this was the view of the Union. Moreover, the enactment of the 14th Amendment strengthened the view that the Constitution is a compact between “the people” and the federal government. The amendment affirms the power of the states to make their own laws, but those laws cannot “abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

There remains a separate guarantee that runs from the federal government directly to each American citizen. Indeed, it was after the Civil War that the notion of being “American” became widely accepted. People now identified themselves as Americans and Virginians. While the South had a plausible legal claim in the 19th century, there is no plausible argument in the 21st century. That argument was answered by Lincoln on July 4, 1861, and more decisively at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

Jonathan Turley is one of the nation’s leading constitutional scholars and legal commentators. He teaches at George Washington University.

Article originally published in the November 2010 issue of America’s Civil War.