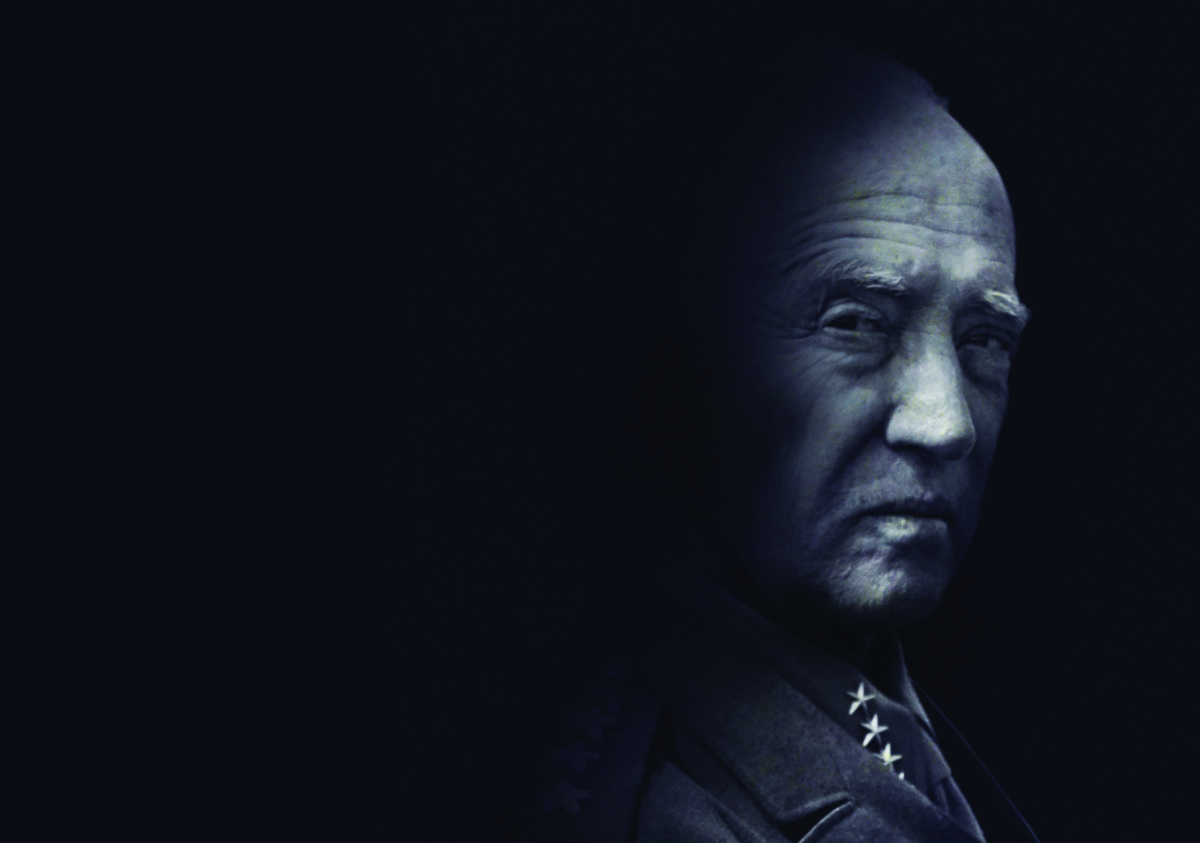

For decades since General George S. Patton’s untimely death in December 1945 there have arisen all manner of conspiracy theories regarding it. They range from the improbable plot of Brass Target, a 1978 film starring George Kennedy as an overweight Patton who was allegedly assassinated in order to stop his investigation of a gold heist by corrupt American officers, to allegations in a widely-read book that Patton was murdered as part of a conspiracy orchestrated by the head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan to prevent the controversial general from running for president in 1948. The truth of what really happened to Patton is more prosaic.

The Circumstances of Patton’s Death

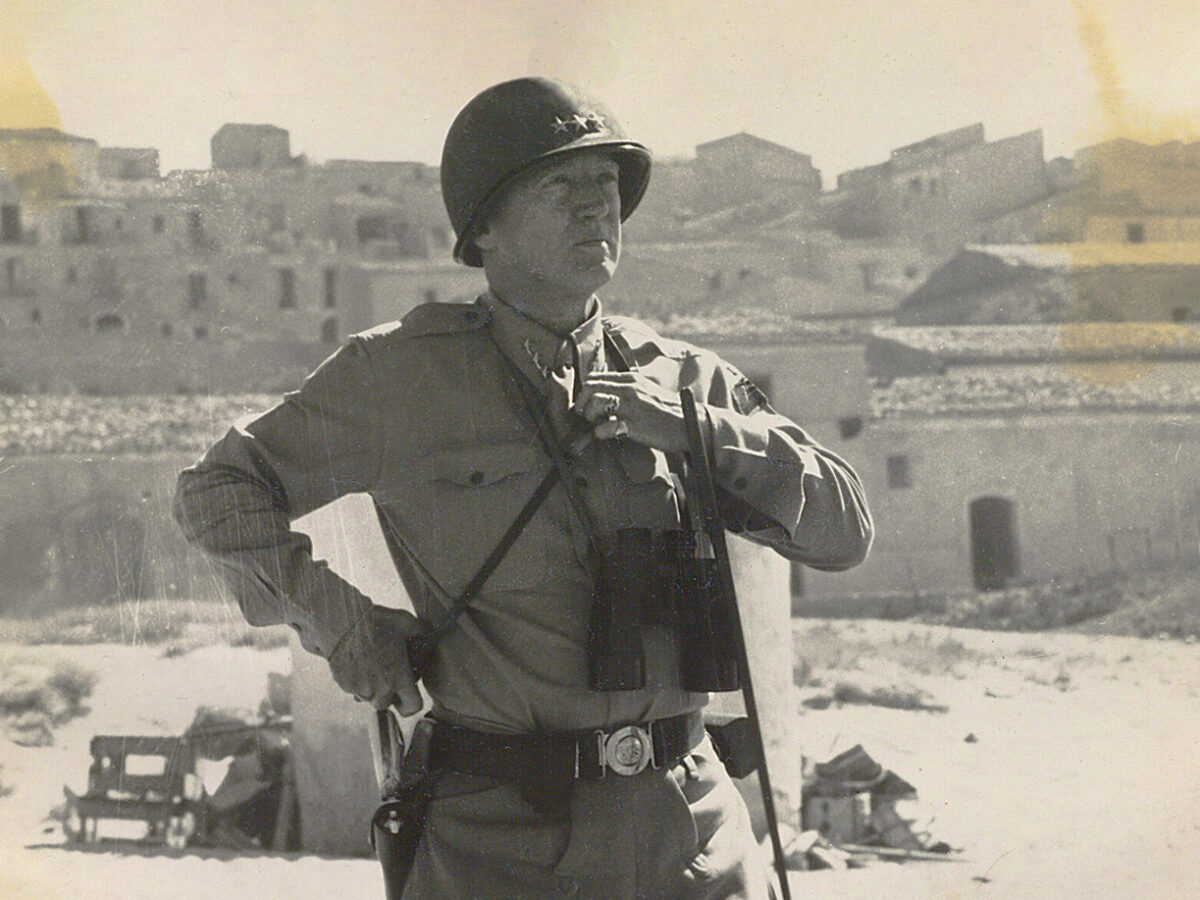

By December 1945, just seven months after Patton’s superb battlefield leadership had played a pivotal role in forcing Nazi Germany’s surrender, America’s greatest World War II field commander was reduced to leading a “paper army.” In late September 1945 the Military Governor of the American Occupation Zone in Germany, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, had relieved Patton of command of his beloved Third U.S. Army, then on occupation duty in Bavaria.

Patton had become a lightning rod of controversy, both for his public remarks and for his employment of former members of the Nazi party to help restore basic services—although this practice was no different from what other, less controversial, occupation commanders were doing, the press was having a field day with the “scandal.” Eisenhower believed he had to act and Patton became the sacrificial lamb.

Patton’s new position was the command of the Fifteenth Army, consisting of only a small headquarters based in the Hessian spa of Bad Nauheim. A dead-end posting for a fiery combat commander like Patton, Fifteenth Army was nothing more than a “paper” command with the primary mission of writing the official history of the European campaign. For weeks the unhappy warrior chafed at what he believed was the manifest unfairness of his relief from 3d Army command for having done his job no differently than any other commander in occupied Germany.

There is ample evidence of Patton’s intense distress during this frustrating time and that his life had reached a vital crossroads. He decided to return home to the United States and retire from the Army. Patton’s departure from Europe was scheduled for December 10.

The evening of December 8, however, Patton’s chief of staff, Major General Hobart R. “Hap” Gay decided that what his boss needed was a diversion to take his mind off his troubles. He proposed a pheasant shoot in the Rhine Palatinate, an area known for its rich game. December 9 would be Patton’s last day in Germany and he readily agreed to a trip from which he would never return.

Sunday, December 9, was typically raw, cold and dismal. About 9:00 a.m. that morning, accompanied by a jeep that would follow behind carrying their guns and a hunting dog, Patton and Gay departed Bad Nauheim in the general’s 1938 Model 75 Cadillac, the last of a special, elegant series designed and built to withstand Europe’s primitive roads.

After his long-time driver, Master Sergeant John L. Mims, had rotated home, Patton was now being driven by a young enlisted man named Horace Woodring. The new driver was known for two things: his “lead-foot” on the Cadillac’s accelerator; and a propensity to break Eisenhower’s ban on fraternization with German fräuleins.

After a detour to the Taunus Mountains where Patton indulged his passion for exploring ancient Roman ruins, the two vehicles were stopped at a military police roadblock in the northern outskirts of the industrial city of Mannheim. Patton, who had gotten soaked touring the Roman ruins, had been sitting in the front seat of the Cadillac to dry out by the car’s heater.

The weather remained icy cold that day and as Patton dismounted to talk to the MP who stopped him he noticed the hunting dog in the jeep was shivering and would freeze to death in that “goddamn truck.” Patton ordered the dog transferred to his car, giving the animal his place by the heater in the front seat of the Cadillac while he continued the trip riding in the back seat. This spur of the moment decision to look after the animal’s welfare and move to the car’s back seat began a chain of events that was about to prove fatal for Patton.

The Accident

At approximately 11:45 a.m., as they were driving through the Mannheim suburb of Käfertal, a U.S. Army two-and-a-half-ton truck suddenly turned left to enter a nearby quartermaster depot. In so doing the truck cut right in front of the Cadillac at the same instant as Patton, his attention riveted on the derelict vehicles littering the area, exclaimed: “How awful war is. Look at the waste.” Momentarily distracted by Patton’s comment, Woodring took his eyes off the road just as the truck traveling at approximately ten miles per hour appeared in front of him.

Recommended for you

Although Woodring slammed on the brakes, it was too late—the Cadillac and the truck collided. The truck’s formidable right front bumper struck the right front side of the Cadillac, smashing the car’s radiator and front fender. Hap Gay, who was sitting in the backseat with Patton, luckily had time to brace himself for the impact. Patton, however, who was sitting unbraced at the time of impact, never saw the collision coming. His body became a “flying missile” rocketing across the spacious back seat area. He was thrust up and forward into the roof, either striking his head on a steel frame that held the glass partition separating the front and rear seats in the “closed” position, or on the clock mounted on the partition—probably both.

Although neither Gay nor Woodring (nor the dog) were even hurt, Patton had been seriously injured. Profusely bleeding from a serious cut across his forehead, Patton exclaimed: “I believe I am paralyzed. I am having trouble breathing.” To Gay he said, “Work my fingers for me. Take and rub my arms and shoulders, rub them hard.” As Gay was responding as ordered, Patton demanded, “Damn it, rub them.” At that point, Gay knew something was very seriously wrong with his boss. As they waited for assistance Patton plaintively said, “This is a helluva way to die.”

To The Hospital

Medical help arrived within minutes and Patton was rushed by ambulance to the One Hundred Fortieth Station Hospital in nearby Heidelberg. Doctors found Patton, his face a bloody mess from the cut, conscious but suffering from severe traumatic shock, his pulse a faintly readable 45, and a barely obtainable blood pressure reading of 86/60. Examination revealed that he had neither sensory nor motor function below the neck.

In the days that followed, Patton was examined by a number of different specialists and consultants. None were even remotely hopeful that he had the slightest chance of ever regaining the use of his limbs.

A top neurosurgeon was summoned from the United States and what he found was that Patton was not only paralyzed from the neck down and was having difficulty breathing but also that his bowels and bladder were paralyzed. An operation to relieve the pressure on his spinal cord would have done nothing to eliminate the paralysis.

Lying motionless for days on end in a hospital bed, Patton’s immobility brought on a small pulmonary embolism in his lung on December 20. If not removed, an embolism will deprive the brain of oxygen and result in death. At this point his doctors thought that at best Patton had about forty-eight hours to live.

Their diagnosis was correct. On the afternoon of December 21, he told his favorite nurse that he was going to die that day. A few hours later he died in his sleep. That Patton had managed to even survive twelve days is attributable to his superb physical condition before the accident.

Conspiracy Theory Origins

According to a sensationalist and, unfortunately, widely-read 2008 “conspiracy theory” book called Target: Patton by Robert K. Wilcox, Patton’s accident was staged and he was actually assassinated. A shadowy former OSS operative named Douglas Bazata has outlandishly claimed that he was directed by agency head Donovan to assassinate Patton. The rear side-window of the Cadillac was allegedly jimmied in advance into a small opening. The plot was carried out on December 9 by himself and a mysterious assassin known only as the “Pole” who used a specially designed weapon that fired a shard of metal into Patton’s head making his injury appear to have resulted from the accident.

This “Star Wars-like” weapon resembling a rifle, Bazata claimed, “could shoot any projectile—rock, metal, ‘even a coffee cup.’” When Patton failed to die, the Polish assassin (whose name Bazata professed not to have known and who was hired independently of him) allegedly finished the job by somehow slipping into the hospital shortly after the accident and administering cyanide. The assassin told Bazata the cyanide he used was made in Czechoslovakia and was “a certain refined form…that can appear to cause embolisms, heart failure and things like that…It can even be timed to kill in a given period such as eighteen to forty-eight hours.”

Copious amounts of unproven, unsubstantiated so-called “evidence” have been proffered that rely on the assertions of Mr. Bazata recounted in Wilcox’s book. Even one of the entries in Bill O’Reilly’s popular “Killing” series volumes, his 2014 book, Killing Patton, repeats Bazata’s outlandish claims.

Among the unanswered and unanswerable questions that render Bazata’s bizarre story unbelievable and impossible are these basic facts: Assassination plots take time to develop and meticulous planning to accomplish; Patton’s decision to go hunting on December 9 was not made until the night before and the route he would follow was never announced.

Even Patton’s own driver was not alerted until approximately 7:00 a.m. on the morning of the trip, just two hours before departure. Until encountering the MP roadblock outside of Mannheim, Patton was riding in the Cadillac’s front seat—there was no reason for anyone to believe that he would have relocated to the rear of the car until, by happenstance, Patton observed the hunting dog freezing and impulsively made the switch.

The claim is also made that the accident was staged and that the driver of the two-and-a-half-ton truck was paid to ram Patton’s car at the precise moment. Yet, with the exception of a handful of men on his personal staff, no one had any knowledge prior to the evening of December 8 where Patton would be the next day, what route he would follow or what time he would arrive at his destination. Incredibly, Mr. Bazata asserts that the “assassination” details were plotted over a period of two days prior to December 9.

Even more absurd and beyond all reason is that William J. Donovan would even contemplate such a vile act, much less recruit an assassin for $10,000 on “orders from way up” on the shaky grounds that “many people want this done.” According to this spurious “murder” theory, Patton was “evil” and “a threat to U.S. objectives”, a “killer” who should “be eliminated.”

Based solely on the unsupported claims of Mr. Bazata, are we to believe that honorable men like Donovan—a holder of the Medal of Honor—and someone above him would order Patton killed on such specious grounds? Inasmuch as Donovan reported only to U. S. President Harry S. Truman, are we also to believe that the President of the United States ordered Patton killed? Or that a weapon that could shoot “even a coffee cup” has ever existed?

Army Carelessness

Unfortunately, sloppiness on the part of the Army has provided grist for the conspiracy theorists’ mills. The Army investigation into Patton’s accident was only perfunctory, and a full-scale formal inquiry was never held. The military police officer who investigated the accident filed a preliminary report that concluded both drivers were careless. Years later, as a Virginia state senator, the officer wrote to the Pentagon for a copy of his report—he was told that it could not be located.

The Army’s failure to thoroughly investigate the fatal accident of so prominent a figure as George Patton is as incomprehensible as it is inexcusable. Perhaps inevitably, these Army failures merely have served to open the door to those who revel in spinning tales of conspiracies, like the ones that swirl around the assassination of JFK. To their convoluted logic, a sloppy investigation equals “cover up” and a misplaced report becomes a sinister, high level “government plot.”

“Murder” theorists also ignore daunting practical problems that conspirators would have had to overcome. In 1945, when communications were primitive (telephone and telegraph/teletype), how could such a plot possibly have been set in motion in a matter of hours?

How was a plan developed and flawlessly carried out on such absurdly short notice? What evidence exists that Donovan (who was both a friend and admirer of Patton) would even consider such a dubious act? How did the assassin(s) know the route and time of Patton’s arrival at the target location? These and a great many other unanswered questions expose the absurdity of the assassination claims.

What is equally disturbing is that a respected newspaper like the UK Daily Telegraph would blindly report such a preposterous claim without rigorously checking the facts. Among the Telegraph’s numerous misstatements was that Patton “was thought to be recovering and was on the verge of flying home” and was killed because “American spy chiefs wanted Patton dead because he was threatening to expose allied collusion with the Russians that cost American lives.” (Daily Telegraph, December 20, 2008) The Telegraph’s article brings to mind 17th-century philosopher Spinoza’s dictum: “He who would distinguish the true from the false must have an adequate idea of what is true and what is false.”

“Not Backed By Any Proof”

Patton’s injuries were so acute that his eventual death was inevitable. It was a tragic ending for a gallant soldier whose legacy is now tarnished by sensationalist purveyors of preposterously false history. By the end of 1945, Patton was a very tired and unhappy soldier who wanted nothing more than to retire to his country home in Massachusetts and write his memoirs. Would they have been controversial? Of that there is little doubt, and his premature death robbed the world of his story.

Yet, controversial memoirs are not unique to Patton and preventing their publication hardly seems a sufficient motive for his murder. Omar Bradley’s bestselling 1951 memoir, A Soldier’s Story, for example, was serialized in Life magazine and was scathing in its criticism of both Patton and Eisenhower; yet it did nothing to harm the enduring reputation of either man.

George S. Patton was a brilliant, opinionated, often irrational and imperfect soldier; but there is not the slightest evidence that he had any political ambitions or that he posed the slightest threat to anyone. However, it did not take an assassination plot to kill Patton, who had once said that he would prefer to die heroically; instead, it took a senseless traffic accident not unlike those which annually kill some 40,000 Americans.

After more than 400 pages of half-truths, what-if’s, undocumented claims and historical mistakes too numerous to count, Target: Patton author Wilcox admits that the alleged plot and assassination of Patton is “not backed by any proof in its darkest possibilities. But the evidence so far unearthed suggests that it could be true.” It is a sad commentary when history is reduced to mere hearsay.