On an unseasonably wet and chilly summer afternoon in 1944, Warsaw was in a state of nervous readiness. For days, young men and women carrying mysterious packages had been seen on the streets. “Tram-cars were occupied with young boys, who unconcernedly occupied even the front platform, reserved ‘Nur Für Deutsche,’ without the Germans present doing anything about it,” eyewitness Stefan Korbonski recalled. “I noticed that one of the boys carried a rucksack from which protruded something resembling a walking stick, wrapped in newspaper and tied with a piece of string. Anyone could see it was the end of a rifle.”

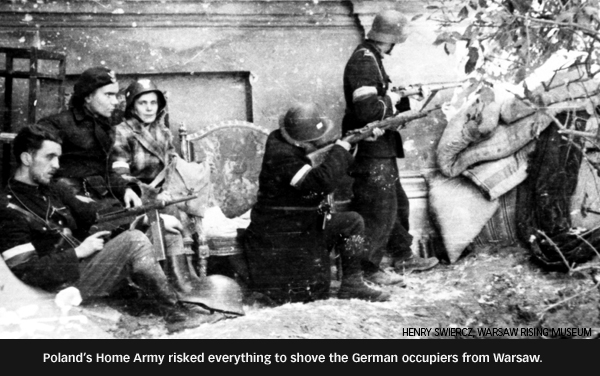

For Warsaw, the scene was extraordinary. Home to a million and a half people before the war, Poland and its capital had been battered by years of occupation after Germany invaded the country in September 1939. Yet far from cowing the nation, German atrocities inspired one of the most dedicated and complex underground resistance movements in Europe. A network of 400,000 men and women known as the Armia Krajowa, or Home Army, blew up train lines, ambushed enemy patrols and convoys, and freed prisoners from SS jails. Most of all, they prepared—in tight secrecy—for the moment when a coordinated strike against the Germans would liberate the city and its people.

The Home Army hoped August 1, 1944, would be that moment. Beginning in late July, the rumble of artillery could be heard in the distance for the first time since the city was seized five years earlier. And this time, it was the Germans who trembled: the guns belonged to the Red Army, whose tanks were probing the city’s easternmost defenses. All across the city, the Home Army’s irregular units, wearing improvised uniforms with red-and-white armbands marking them as members of the underground military, began moving into preassigned positions. The Poles—who had had already lost hundreds of thousands of people to the 1939 invasion, to the Holocaust, and to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising a year earlier—aimed to oust their Nazi oppressors, with tacit Soviet help.

The two months of bitter urban combat that followed would become one of the war’s most courageous, disastrous, and ultimately misunderstood episodes. In their desperation to reclaim their freedom, the Poles failed to fully grasp the weakness of their geopolitical situation; theirs was a country with few friends. The Soviets preparing to supplant the Germans in Warsaw had scant regard for Poland or its independence, while Britain and the United States were caught up in an alliance with the Soviet regime in an effort to defeat the Nazis and not in a strong position to help. As a result, Warsaw was left hanging, the Rising turned ruinous, and Poland was dropped by one totalitarian neighbor into the hands of another—an outcome that shaped the perception of the battle for decades after the war.

This wasn’t the first time Poland had been the odd man out in the cynical world of bilateral alliances. The Soviet-German Nonaggression Pact, signed in secret in August 1939, included a provision to divide Poland between the Soviet Union and Germany—and that’s what happened following Germany’s invasion of Poland. Two years later, Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union led to the wartime alliance between Churchill, Stalin, and Roosevelt, which could have benefitted Poland. But politicians and diplomats in London and Washington were reluctant to jeopardize their relationship with Moscow by sticking up too forcefully for a pawn in the strategic chess game.

The Poles, however, were determined to fight. More than 200,000 Polish soldiers escaped to the West after the German invasion, to fight with the Allies everywhere from the Battle of Britain to Monte Cassino. At the same time, a massive underground army was organized in occupied Poland. The Home Army was the third largest armed force on the continent until D-Day. When Polish Jews inside the Warsaw Ghetto rebelled against their SS jailors in January 1943, the Home Army supplied the fighters with weapons. But the army also held back, not willing to commit to a general uprising while the German army was still the dominant force on the continent.

The Poles, however, were determined to fight. More than 200,000 Polish soldiers escaped to the West after the German invasion, to fight with the Allies everywhere from the Battle of Britain to Monte Cassino. At the same time, a massive underground army was organized in occupied Poland. The Home Army was the third largest armed force on the continent until D-Day. When Polish Jews inside the Warsaw Ghetto rebelled against their SS jailors in January 1943, the Home Army supplied the fighters with weapons. But the army also held back, not willing to commit to a general uprising while the German army was still the dominant force on the continent.

As the tide of war turned against Berlin, Poles saw reasons for hope. Throughout the winter and spring of 1944, the Red Army moved steadily west, pushing the Wehrmacht relentlessly in front of them. By summer, Soviet artillery could be heard just over the horizon, hammering German defenses in the forests on the Vistula River’s eastern bank. The leaders of the Home Army, and the Polish government in exile, saw an opportunity: if they could take advantage of German disarray to gain control of their capital before the arrival of the Red Army, a major symbolic victory would be achieved—one that might give the Poles leverage in any postwar negotiations over their country’s future.

But they also knew that the underground was ill-equipped for a protracted struggle with the German army. Only a quarter of the 50,000 underground soldiers in the city had real weapons, and food and ammunition were in desperately short supply. That made their timing critical: move too early and German troops could focus all their might on crushing the resistance, but waiting until the Soviets had pushed the Wehrmacht across the Vistula would be equally ruinous. As Home Army commander Tadeusz Komorowski—who went by the pseudonym General Bór—wrote in his memoirs, “The city would become a battlefield between the Germans and Russians, and would be reduced to ruins.”

Komorowski knew one of his enemies intimately. The underground general had served in the Austrian army during World War I and spoke perfect German. Forty-nine years old, he was a former Olympic equestrian and led a cavalry regiment before the war. He had commanded the Home Army for more than a year, operating in plainclothes and sneaking from safe house to safe house around the capital.

On the evening of July 31, in an apartment in the center of the city, Komorowski assembled the Home Army’s leadership. That month, Soviet radio broadcasts had encouraged Poles to resist the German occupation. Soviet tanks had been sighted on the eastern edge of the city; underground observers said that German troops were abandoning their positions. A failed bomb plot against Hitler the week before suggested that support for the Nazis was crumbling in Germany, as well. Weighing the limited information against the risk of delay, Komorowski gave the order to attack preassigned targets at 5 p.m. on August 1, 1944. Twenty-two runners set off in all directions to spread the news. In less than 24 hours, Warsaw would rise.

Inevitably, scattered fighting broke out before 5 p.m. Still, the occupying forces were caught unprepared if not entirely by surprise. Within hours, the Home Army had captured a host of strategic spots, from the main post office and power station to the city’s tallest building and several key German arsenals and supply dumps. Units of young men armed with pistols and homemade bombs took on—and took out—German tanks, and even captured a few. They used one of the captured tanks to liberate a small concentration camp on the site of the razed Warsaw Ghetto.

Inevitably, scattered fighting broke out before 5 p.m. Still, the occupying forces were caught unprepared if not entirely by surprise. Within hours, the Home Army had captured a host of strategic spots, from the main post office and power station to the city’s tallest building and several key German arsenals and supply dumps. Units of young men armed with pistols and homemade bombs took on—and took out—German tanks, and even captured a few. They used one of the captured tanks to liberate a small concentration camp on the site of the razed Warsaw Ghetto.

It quickly became apparent, however, that the military effort would be hard to sustain. In the first day of fighting, almost 2,000 Poles had been killed compared to roughly 500 Germans. Huddled in a former furniture factory, Komorowski and the rest of the Polish high command got reports that key objectives, like the airport and the two main bridges across the Vistula, were still in German hands.

Still, in wide stretches of the city, Poles owned the streets for the first time in five years. On August 2, one young soldier marched through the liberated city. “The distance of one or two kilometers was free of Germans, and thousands of people lined the streets, throwing flowers and crying,” he recalled. “It was a very moving scene.”

In Berlin, the mood was far different. News of the Rising had reached the German high command within the first half hour. Heinrich Himmler, commander of the SS, informed Hitler personally—and with a certain degree of satisfaction. “The action of the Poles is a blessing,” he told the führer. “Warsaw will be liquidated, and this city, which is the capital of a sixteen- to seventeen-million-strong nation that has blocked our path to the east for seven hundred years…will have ceased to exist.”

On August 3, Himmler issued orders to wipe Warsaw from the map. Every inhabitant was to be killed, every house to be blown up and burned. In the Nazi mindset of racial cleansing and Lebensraum, military defeats were mere temporary setbacks; the elimination of Poland would be forever.

To bolster the beleaguered German garrison in Warsaw, Himmler threw together a motley collection of units, including some of the most notorious in the SS. Cossacks, Azerbaijanis, and antipartisan SS units recruited from the Belarusian and Ukrainian countryside entered Warsaw five days after the Rising began. Militarily, their involvement was near meaningless. Their job was merely to kill—indiscriminately.

“For two days they concentrated on massacring every man, woman, and child in sight,” historian Norman Davies wrote in his sweeping history Rising ’44: The Battle for Warsaw. Tens of thousands of civilians were killed in just a few days in neighborhoods on the western edge of the city. John Ward, a British lieutenant who found himself in Warsaw after being liberated from a POW camp, began sending radio dispatches back to London on behalf of the Home Army. “The German forces make no difference between civilians and troops of the Home Army,” he reported. “Ruthless destruction of property goes on unhindered by any scruples. There are thousands of civilian wounded men, women, and children suffering from the most horrible burns and in some cases from shrapnel and bullet wounds.”

Elsewhere, the Wehrmacht deployed its full arsenal against the Home Army. Sixty-eight-ton Tiger II tanks rumbled toward makeshift barricades made of torn-up flagstones manned by boys with rifles and homemade grenades. On rail lines around the city, armored trains equipped with heavy artillery rolled back and forth, seeking out the best angles of attack. Several massive “Karl” siege mortars capable of launching two-ton shells for miles trundled around the city, followed by dedicated cranes and ammunition carriers.

The most effective weapons were far more modest. Civilians were tied to tanks or forced to walk in front of advancing German infantry as human shields. To deal with barricaded streets and dug-in defenders, the Wehrmacht deployed tracked mines called Goliaths. Like remote-controlled minitanks, the Goliaths packed 200 pounds of explosives. Using a joystick, operators guided them up to a target and detonated the payload, all from a safe distance. (Polish soldiers soon learned to cut the minitanks’ long guidance cables.)

Across much of the city, the Poles fought the German army to a near standstill. The Home Army units took shelter in cellars, knocking down walls to create tunnels leading from building to building. They moved through the city’s sewers and from rooftop to rooftop, eluding and evading German patrols. Women served as nurses, stretcher-bearers, and messengers. Polish Boy and Girl Scouts created a postal service for the resistance, running letters through the war zone.

To conserve ammunition, commanders instituted a “one bullet, one German” rule and fighters were to fire only when a kill was guaranteed. As a result, more Germans were killed than wounded. Home Army platoons with too few rifles passed weapons off between watches. “They showed themselves far superior in the arts of entrapment and surprise, frequently nullifying or reversing laborious German offensives that were highly predictable,” Davies wrote. “After the first week…, Warsaw became the scene of a long, relentless battle of attrition.”

Unbeknownst to the beleaguered Home Army, the diplomatic front was seeing some fierce fighting as well. Komorowski had badly misjudged the Soviet Union’s desire for control over Eastern Europe. Stalin had no interest in an independent Poland, and recognized an opportunity to let the Germans do his dirty work for him. In telegrams to Churchill and Roosevelt, the canny Soviet leader referred to the Home Army as a poorly led “gang of criminals who embarked on the Warsaw adventure to seize power,” and who had “exploited the good faith of the citizens of Warsaw, throwing many almost unarmed people against the German guns, tanks, and aircraft.”

Unbeknownst to the beleaguered Home Army, the diplomatic front was seeing some fierce fighting as well. Komorowski had badly misjudged the Soviet Union’s desire for control over Eastern Europe. Stalin had no interest in an independent Poland, and recognized an opportunity to let the Germans do his dirty work for him. In telegrams to Churchill and Roosevelt, the canny Soviet leader referred to the Home Army as a poorly led “gang of criminals who embarked on the Warsaw adventure to seize power,” and who had “exploited the good faith of the citizens of Warsaw, throwing many almost unarmed people against the German guns, tanks, and aircraft.”

Even worse, Soviet generals halted their troops within a few miles of the city and held their positions for most of August—a suspicious move that caught Churchill’s eye. “It is certainly very curious that at the moment the Underground Army has revolted, the Russians should have halted that offensive against Warsaw and withdrawn some distance,” the prime minister told one of his aides. “For them to send in all the quantities of machine-guns and ammunition required by the Poles for their heroic fight would involve a flight of only 100 miles.”

Stalin’s antipathy went still further. He also declined British and American requests to allow planes flying in ammunition and supplies for the Home Army to land and refuel in Poland’s Soviet zone. On August 18, after weeks of diplomatic wrangling, the Soviets made their position plain. The American ambassador in Moscow reported that “the Soviet Government cannot of course object to English or American aircraft dropping arms in the region of Warsaw. But they decidedly object to British or American aircraft…landing on Soviet territory, since the Soviet Government do not wish to associate themselves either directly or indirectly with the adventure in Warsaw.” This meant Allied planes had to fly from and return to Brindisi, Italy—a round trip of more than 1,600 miles, crossing not only the Alps but much of Germany and Austria. In the skies over Warsaw, they faced antiaircraft fire from the Germans—and, quite possibly, from their Soviet allies as well.

Despite these difficulties, 306 bombers loaded with supplies and ammunition made the supply runs, many flown by Polish pilots seconded to the RAF. Hundreds of antitank weapons, 1,000 Sten guns, and nearly two million rounds of ammunition got to the Polish fighters. But roughly one bomber was shot down for every ton of supplies delivered—an unacceptable loss rate—and the supply flights were halted on September 18.

As long as the Luftwaffe stayed on the west side of the Vistula River, the Soviets were content to cede the airspace over Warsaw to the Germans. In his memoirs, one Home Army fighter recalled the same four German bombers dropping incendiary charges on the city every 45 minutes, pausing just long enough to land at the airport on the outskirts of town to reload. “They had the sky to themselves; the Red Army was stationed just across the Vistula, but not a single Soviet fighter challenged them.”

As the battle progressed, the Home Army gave ground to the German forces, neighborhood by neighborhood. The first sector to fall was Old Town, the historic heart of the city. In late August, after nearly a month of fighting in the rubble of centuries-old buildings, Komorowski ordered it abandoned. The primary escape route was the city’s sewers, requiring exhausted fighters to crawl on all fours for nearly four miles through stagnant water. German soldiers dropped grenades through manhole covers and pumped in poison gas. “I spent the most horrendous day of my life down there,” one young soldier wrote later. “People could not cope psychologically; they were constantly stepping on corpses.” Still, 5,000 managed to make it out and went to reinforce the areas to the north and south.

As the fighting stretched into September, conditions in the stricken city deteriorated. Civilians trapped in their houses began to starve, and cases of typhus rose. Germans burned field hospitals filled with wounded soldiers to the ground; on the edge of Old Town, hundreds were buried alive when the church basement in which they were sheltered was bombed.

Some flickers of hope remained. But after a month and a half of fighting, they blinked out, one by one. Aside from the Home Army, which answered to Poland’s London-based government in exile, there was a small force of Polish troops under the Red Army’s command. In mid-September, with Soviet troops in control of the east bank of the Vistula, the so-called People’s Army managed to take the river’s opposite bank. But Soviet commanders withdrew them when their initial attempt to seize the bridges over the river—with halfhearted support from their Soviet allies, a no-lose proposition for Stalin—failed. A few days later, British and American bombers, in what would turn out to be one of the final supply runs of the battle, dropped 1,800 containers of materiel. But the planes had veered off course, and nearly all of the supplies were picked up by Germans or destroyed. The final blow came when British commanders ordered the England-based Polish Parachute Brigade, a unit created in 1941 specifically to support a national uprising, to the Netherlands for Operation Market Garden instead of to Warsaw.

Some flickers of hope remained. But after a month and a half of fighting, they blinked out, one by one. Aside from the Home Army, which answered to Poland’s London-based government in exile, there was a small force of Polish troops under the Red Army’s command. In mid-September, with Soviet troops in control of the east bank of the Vistula, the so-called People’s Army managed to take the river’s opposite bank. But Soviet commanders withdrew them when their initial attempt to seize the bridges over the river—with halfhearted support from their Soviet allies, a no-lose proposition for Stalin—failed. A few days later, British and American bombers, in what would turn out to be one of the final supply runs of the battle, dropped 1,800 containers of materiel. But the planes had veered off course, and nearly all of the supplies were picked up by Germans or destroyed. The final blow came when British commanders ordered the England-based Polish Parachute Brigade, a unit created in 1941 specifically to support a national uprising, to the Netherlands for Operation Market Garden instead of to Warsaw.

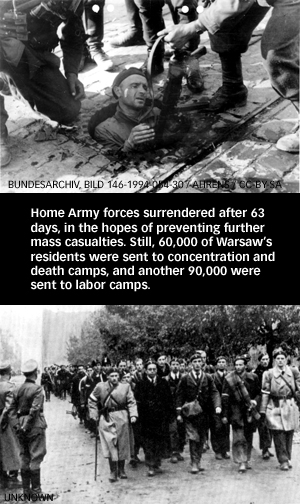

Home Army commanders realized further fighting was of no use. On October 2, 1944, they capitulated. The negotiated surrender included an agreement to treat the surviving Home Army forces—11,668 men and women—as prisoners of war. In return, Warsaw was to be completely evacuated. More than half a million civilians were forced to leave the city. Many were sent to Germany as slave laborers. Others found refuge in the countryside or were held in camps until the war ended.

Warsaw’s underground army had held out for 64 days, winning a kind of grudging respect from their foes. “In truth they fought better than we did,” a Wehrmacht lieutenant wrote to his family after watching the battered, tired Home Army soldiers march by, four abreast. “In spite of everything, the most heroic fighting, given the conditions, was done by the bandits themselves. And if London, which ruled on everything down to the last detail, had not ordered the capitulation…, much more blood would have flowed.”

As it was, an estimated 200,000 civilians died during the two-month struggle. More than half of the Home Army fighters in Warsaw at the beginning of the battle were killed. The city itself was shattered, with 93 percent of its buildings destroyed—a systematic, building-by-building annihilation far worse than Dresden or Hamburg that continued even after the Home Army’s capitulation.

A few people, mostly Jews who knew that surrender meant certain death, stayed hidden in the city’s ruins. They included the pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman, whose wartime experiences were chronicled in the 2002 film The Pianist. Warsaw “now consisted of the chimneys of burnt-out buildings pointing to the sky, and whatever walls the bombing had spared,” Szpilman wrote in his memoirs. “A city of rubble and ashes under which the centuries-old culture of my people and the bodies of hundreds of thousands of murdered victims lay buried, rotting in the warmth of those late autumn days and filling the air with a dreadful stench.”

Even before the Rising was over, Polish and British politicians were debating whether it was a heroic gesture or simply a colossal mistake. Some postwar historians—influenced by Communist propaganda that turned the story inside-out—condemned the Rising leaders for the slaughter of 1944, charging that they needlessly sacrificed a generation of young heroes.

Even before the Rising was over, Polish and British politicians were debating whether it was a heroic gesture or simply a colossal mistake. Some postwar historians—influenced by Communist propaganda that turned the story inside-out—condemned the Rising leaders for the slaughter of 1944, charging that they needlessly sacrificed a generation of young heroes.

More recently, blame for the Rising’s failure has fallen squarely at the feet of the Soviets. Stalin was playing a double game that wasn’t apparent to the Americans at the time, in part because President Franklin D. Roosevelt tended to believe Stalin. The Poles were deceived as well; Komorowski and his fellow commanders made their decision to fight based on what seemed to be safe assumptions at the time. “Ever since the outbreak of the Rising, the people of Warsaw had been living by listening, listening to hear the Soviet guns,” underground commander Stefan Korbonski, who spent months in Soviet captivity before escaping to the West, wrote in his postwar memoirs. “It never even occurred to anyone that the Soviets might deliberately stop their offensive, so as to enable the Germans to destroy the City of Warsaw.”

Soviet troops didn’t enter Warsaw proper until January 17, 1945. Even then, members of the Home Army were imprisoned or executed by Communist officials. (Komorowski spent the remainder of the war in the notorious Colditz officer’s prison, and escaped to England after the German surrender.) For Poles, the Allied victory over Nazi Germany was bittersweet. As Pawel Ukielski, the deputy director of a new museum in Warsaw devoted to the Rising, explains: “One occupation was just exchanged for another.”

Despite the dramatic fighting and the tremendous losses, the Warsaw Rising is one of the lesser-known conflicts of the war. The reason is simple: publicizing the events of August and September 1944 was in nobody’s interest during the Communist era. For the ruling regime in Poland, it was a direct attack on their legitimacy. The struggle has been largely forgotten outside Poland as well. The Rising was an uncomfortable reminder that Poland and the nations of central Europe had been cynically abandoned to Stalin during and after the war. None of the German officers responsible for the brutal reprisals against civilians in the city were tried at Nuremberg. In fact, the events of August and September 1944 were barely mentioned, for fear of roiling the tense relationship with Moscow.

Since the fall of Communism in 1989, the Rising has become a powerful symbol of pride for Poles. Even though the battle was a military failure, Ukielski says, “it shows that Poles never surrendered, that they were fighting from the very beginning to the very end. We’re not celebrating a defeat, but rather the heroism and will of independence.” He adds, “In a metaphysical sense, after 1989 the Warsaw Rising was finally won.”

Since the fall of Communism in 1989, the Rising has become a powerful symbol of pride for Poles. Even though the battle was a military failure, Ukielski says, “it shows that Poles never surrendered, that they were fighting from the very beginning to the very end. We’re not celebrating a defeat, but rather the heroism and will of independence.” He adds, “In a metaphysical sense, after 1989 the Warsaw Rising was finally won.”

Today, the new Warsaw Rising Museum attracts crowds of schoolchildren and grownups—and the occasional emotional veteran of the conflict. Outside it, Communist-era concrete buildings erected after the war mingle with gleaming skyscrapers built in the last decade—reminders of the capital’s bleak wartime experience merging with the promise of its future.

Andrew Curry is a journalist living in Berlin, Germany. He has been traveling to Warsaw for nearly 30 years, and spent a semester studying at the University of Warsaw’s International Relations Institute. His work can be found online at andrewcurry.com.