In the June issue, we published Part 1 of author Ted Savas’ account of Georgia’s Augusta Arsenal in which he described the arsenal’s founding and operation. Here in Part 2, he argues that Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman could have shortened the war if he had attacked the arsenal in 1864.

The Union Army’s failure to capture the Augusta Powder Works and its associated arsenal was perhaps the greatest strategic mistake of the entire Civil War. The Confederacy could not have survived for any significant length of time without the powder mill. Few scholars seem to realize that fact, however, despite the passage of more than 150 years and extensive documentary evidence.

Colonel George W. Rains, who oversaw the erection of the powder works—the South’s largest industrial project of the war and the Confederacy’s only reliable large-scale source of gunpowder—understood the city’s significance more than any other officer or politician in gray. In what could only have been hair-pulling frustration, he spent much of the war pleading with his Richmond superiors to defend it properly.

Fortunately for Rains, the Federals inexplicably never targeted Augusta. The Union brass knew of its importance, and Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant empowered Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman with discretionary orders to destroy it during the 1864 March to the Sea. For eight long months, Sherman enjoyed one opportunity after another to raze the powder mills and arsenal and end the war. But he failed to do so.

The first hint of Augusta’s vulnerability occurred in November 1861 when Federal troops landed just 128 miles away on Tybee Island at the mouth of the Savannah River. A Union gunboat thrust up the river could have imperiled Augusta, and Rains warned Richmond that the loss of the powder works would be “a matter of no small injury to the state and Government.” Rains immediately conferred with Robert E. Lee, who at that time commanded the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, about blockading the river below Augusta. In February 1862, Rains arranged for the placement of water obstructions 45 miles downriver at Shell Bluff. An 8-inch Columbiad, nearly worthless 6-pounder iron guns, and rifle pits were positioned to fire down the river, but his numerous pleas for troops to man the posts vanished within Richmond’s bureaucracy.

Richmond suggested that Rains supply his own men, but the commander retorted that the city of Augusta had “almost exhausted itself in sending volunteers to the war….There is no chance of a force being raised here.” Chief of Ordnance Josiah Gorgas understood and supported Rains’ efforts, and George Randolph, secretary of war until November 1862, reluctantly directed that troops be stationed there, but the matter was never acted upon. Forced once again to rely on his own ingenuity, Rains began raising companies of clerks from the Augusta workforce, but despite its importance, Shell Bluff was never routinely garrisoned.

“I have drawn the attention of the War Department to the defenseless condition of this city

George W. Rains to C.S.A. Secretary of War James Seddon, July 23, 1863

and have exerted myself in every possible way…without success.”

Augusta’s vulnerability to a mounted raid became obvious in early May 1863 when Union Colonel Abel Streight’s cavalry raid ended in disaster just west of Rome, Ga. Augusta was not Streight’s objective, but the fact that Union troopers could cover hundreds of miles before being stopped was not lost on Rains. The Union high command, however, ignored the tutorial of possibilities that had galloped unchecked across the Southern landscape. So too did the brain trust sitting in Richmond, which continued to ignore Rains’ pleas for assistance.

On July 23, 1863, the perpetually frustrated Rains dispatched a scathing letter to Secretary of War James Seddon. Enemy cavalry was “within striking distance” just 90 miles away in Pocotaligo, S.C., warned Rains, and yet the facility remained essentially unguarded. “The extreme value of the city of Augusta, including the Government works, to the Confederacy is so apparent that it does not require that I should draw attention thereto.” The upset officer continued that he had frequently, “drawn the attention of the War Department to the defenseless condition of this city and have exerted myself in every possible way…without success.”

Rains went on to presciently point out that the enemy “has seen the error of operating on the extremities, and are now prepared to strike at the vital organs” in Georgia. The loss of Augusta, he schooled Seddon (and by extension, President Jefferson Davis), “would be fatal to the Confederacy.”

When local men refused to organize because they could be called up for service away from Augusta, Rains pleaded once more with the war secretary to exempt the militia from Confederate service. This time Seddon agreed. Rains organized 20 local companies by the end of the year. Most of the men, however, were government clerks, the old and the young, and others unfit for frontline service. Augusta remained essentially defenseless as the calendar slipped into 1864.

Other problems mounted. The Army of Tennessee lost a great amount of ordnance during its rout on Chattanooga’s Missionary Ridge in November 1863. Rains supplied that battered army with many complete artillery batteries, hundreds of thousands of artillery and small arms rounds, and tons of gunpowder. Without Rains’ effort, the Army of Tennessee would not have been able to resist the coming Union spring offensive into Georgia.

That offensive began in early May 1864 when Sherman moved his army group in northern Georgia against General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee. Two days earlier, the Army of the Potomac pushed across the Rapidan River in central Virginia and engaged Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in the Wilderness. The dual thrusts, with other associated movements, triggered a nearly ceaseless series of engagements that would not end until the Confederacy’s final surrender.

After a bitter summer of fighting, Atlanta fell on September 2. Its capture sent a tidal wave of panic gushing 130 miles eastward to engulf Augusta. Sherman was well aware of Augusta’s importance to the Confederate war effort and on September 20 he wrote Grant that Augusta housed “the only powder-mills and factories remaining in the South.” It seemed to be only a matter of time before he paid the city a visit.

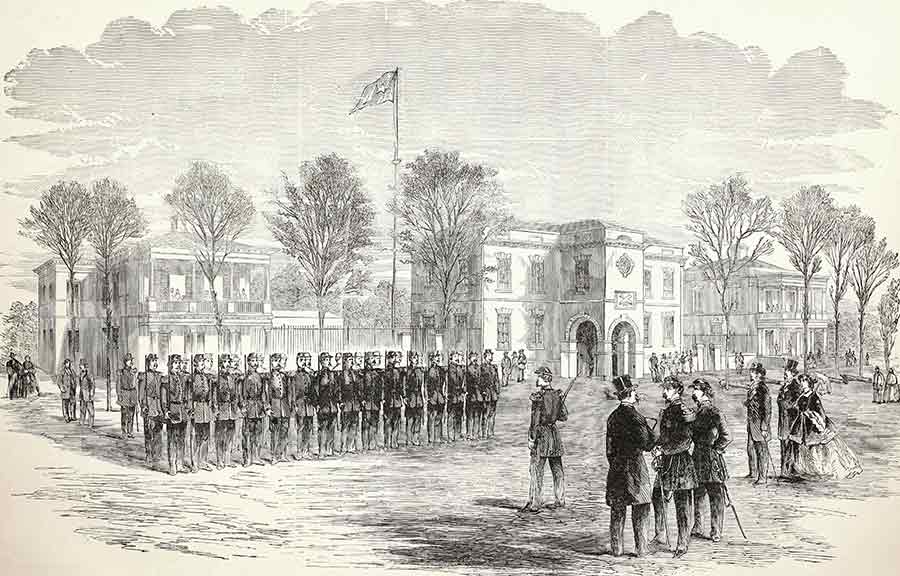

Rains meanwhile was frantically trying to replace Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood’s ordnance train that was destroyed at Atlanta. Rains employed women at the Augusta Arsenal to make up for a shortfall of male workers, and turned out 75,000 cartridges a day—in addition to tons of gunpowder, thousands of artillery shells, hand grenades, and other desperately needed items.

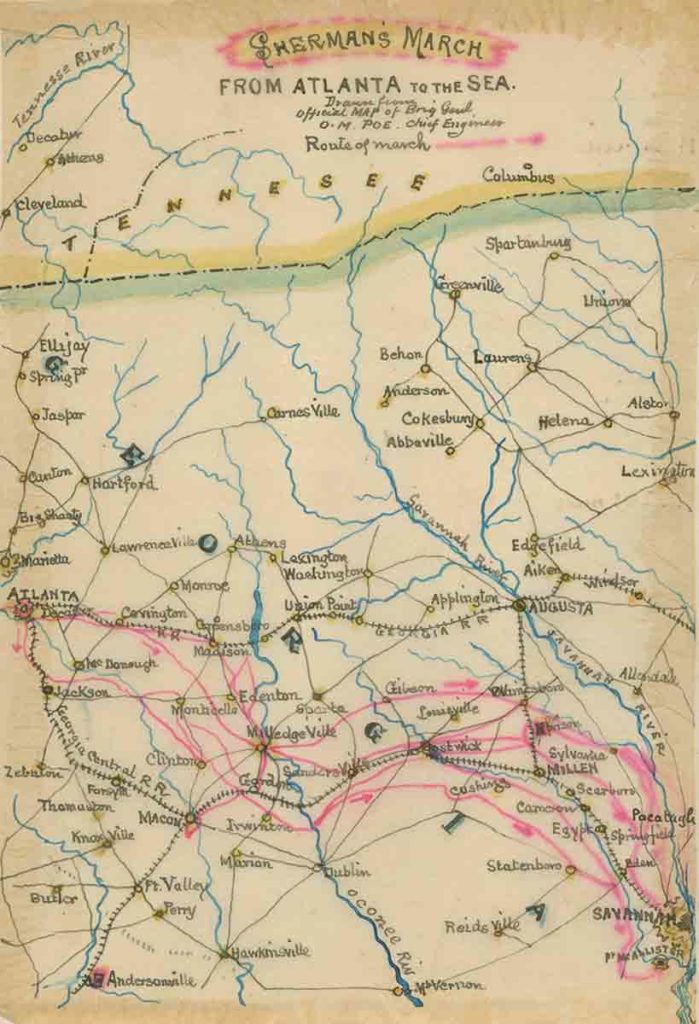

While Rains toiled, Sherman planned. The Union commander put the torch to Atlanta on November 15 and, with four infantry corps and a large division of veteran cavalry, marched east across a broad front into the bowels of the state. Several important munitions centers, including Augusta and Macon, were now within easy reach. The exterior wings of Sherman’s command could have taken or destroyed both cities with ease.

Rains and other Confederate authorities had no way of knowing that Sherman would feint at Macon and Augusta to divide the paltry number of Rebel soldiers available to oppose him, and then drive through the yawning gap to link up with the Union Navy at Savannah. That decision was the biggest strategic mistake of his career, and he would repeat the same mistake under nearly the exact same circumstances three months later. The consequences would lengthen the war by months and increase the casualty lists by many tens of thousands of men.

When Sherman left Atlanta, Augusta remained unprepared to meet the Union threat. The city’s light earthen defenses remained inadequate and unfinished, and they were so ineptly designed that they would not have saved the powder works even had they been fully manned. Few soldiers, however, were available to defend Augusta. Troops of all stripes were being rushed to the city, but by November 20 only 2,000 “locals and convalescents” were present. Augusta’s military commander, Brig. Gen. Birkett Fry, sent a disquieting telegram to Richmond two days later: “I can as yet count only 4,000 for defense here.” He ended his message with the pessimistic observation that the “people show little spirit.”

Very few of Fry’s men were veteran frontline troops. Now in a panic, Richmond scrambled to act. The War Department cast a wide net in search of generals, including Braxton Bragg, William Hardee, and Richard Taylor. Davis ordered these men and others to report to Augusta. Veteran infantry, artillery, and cavalry were required, however, not a cabal of squabbling mediocrities and hand-wringing politicians issuing proclamations and prayers. The odds of mustering a successful defense of the city had already passed.

The very real threat of losing the Confederacy’s only reliable source of gunpowder left Rains with two very unattractive alternatives: remain in Augusta or move the mills. Staying put seemed to guarantee the powder works’ destruction. Moving, however, required finding another suitable location not in the path of a roving Union army or a column of cavalry—which was probably impossible at this late date. Rains also had to consider the mill’s delicate and irreplaceable equipment. Southern railroads were notorious for misplacing and damaging machinery.

Even if such a move was successful, the entire works would have to be reassembled—a process that would take weeks if it could be done at all. Rains made the decision to mobilize all of his workers for a gargantuan assignment: the dismantling of the Augusta Powder Works and the transfer of its vital machinery via the South Carolina Railroad over the Savannah River to Columbia, S.C.

While Rains organized for the move, he also worked to produce as much saltpeter, sulfur, and charcoal (the three ingredients of gunpowder) as possible before the evacuation. The disassembling of the machinery began on November 21. Within just a few days the crucial components were inside railcars in Columbia.

To the Confederate’s astonishment, Sherman bypassed Augusta and reached the outskirts of Savannah on December 10. Rains and his crew quickly returned to Augusta and began to unload and reassemble the machinery. Despite their best efforts, production did not begin again until Augusta had been offline for 34 critical days.

Two months later in February 1865 Sherman repeated his error, marching into the Carolinas while once more using two cities—this time Augusta and Charleston, S.C.—to divide meager Confederate forces and march between them. Sherman had again avoided Augusta and tramped northward. The puzzled Rains had spent a few days tearing down equipment, but when he realized Sherman had no intention of visiting, he put it back together a second time.

Few historians have seriously questioned Sherman’s strategic decisions from midsummer 1864 through February 1865. Fewer still have deeply researched just what was at stake during the Atlanta Campaign, the March to the Sea, and during the early days of Sherman’s 1865 Carolinas Campaign. Augusta is rarely mentioned in books and articles, and the existence and importance of the powder mills and arsenal are almost never discussed—even in passing.

There is no evidence that Sherman’s biographers or authors who have written on his 1864-65 campaigns grasp what Augusta meant to the Confederacy. Nor is there proof they have even cast a glance at Augusta’s voluminous ordnance records, let alone extrapolate their meaning to the war at large to properly judge the consequences of Sherman’s decision-making. After the war, Sherman took some criticism about his failure to destroy Augusta, and he defended himself by claiming that he didn’t want to get bogged down in a fight there. Besides, he argued, there was no need to take Augusta when he left Atlanta because he intended to destroy the railroads Rains needed to ship his gunpowder. Sherman’s casual rebuttal is not only untrue but illogical.

First, the destruction of Augusta was well within the objective of Sherman’s orders. A month before the opening of the Atlanta Campaign, Grant wrote to his western general: “You I propose to move against Johnston’s army, to break it up, and to get into the interior of the enemy’s country as far as you can, inflicting all the damage you can against their war resources [emphasis added].” Most historians ignore that final highlighted clause. Grant also gave Sherman carte blanche as to how to conduct his operations: “I do not propose to lay down for you a plan of campaign, but simply to lay down the work it is desirable to have done, and leave you free to execute it in your own way [emphasis added].”

Second, Augusta was within Sherman’s reach for some eight months, from summer 1864 through February 1865, while the city was largely undefended with virtually no garrison and few earthworks and forts. The city was just 130 miles east of Atlanta and linked by rail. Sherman was aware of the wide-ranging cavalry thrusts. He ordered one of his own in late July 1864 when he tasked Maj. Gen. George Stoneman to ride around Atlanta, wreck the Macon Railroad, and cut off the city. Stoneman didn’t follow orders and met defeat near Macon—but covered more than 100 miles.

By mid-July the Confederate Army of Tennessee was pinned against Atlanta. Knowing Augusta’s fundamental value, why didn’t Sherman detach a mixed-arms strike force and end the war by destroying the powder works? Sherman didn’t even try to use the resources at his disposal to destroy the South’s sole-source gunpowder-producing city, and no record exists that he (or Grant or President Lincoln, for that matter) ever gave it serious consideration.

Indeed, Sherman casually dismissed the effort in his memoir: “I had long before made up my mind to waste no time on either [Macon or Augusta].” He went on to make the nonsensical argument that when he left Savannah to march north in early 1865, he again bypassed Augusta because “The enemy occupied the cities of Charleston and Augusta, with garrisons capable of making a respectable if not successful defense.”

Sherman seems to have thought it made more sense to expend his efforts from May to September 1864 directly fighting a formidable Confederate army across more than 100 miles of difficult terrain in the hope of capturing the heavily defended and fortified city of Atlanta. Instead he could have launched a faster offensive to Augusta with minimal interference.

Third, contrary to his postwar boast, Sherman had no idea when he set out on the March to the Sea in November 1864 that he would be in a position three months later to cut the railroads feeding Augusta. Sherman intended to board ships in Savannah and sail for Virginia! It was not until the Union general was on the coast, and only after a lengthy discussion with Grant, that the plan was settled on to march through the Carolinas. It was only then that the vital railroads leading to the war’s last major battlefields were finally (and sometimes temporarily) cut.

Augusta’s central location required the clipping of every line on all points of the compass, and the garrisoning of troops along those broken lines, in order to blockade Rains’ mills effectively. Sherman could not have known exactly where he would be months in advance, and he never developed a plan to isolate Augusta until at least early 1865, if even then.

Finally, the day-to-day ordnance records kept from summer 1864 through April 1865 record in painstaking detail that Rains continued to produce and ship gunpowder and other munitions across the South. Rains organized work parties to repair destroyed rail lines, and he reconnected sizable portions of the crucial network west and south of Augusta with repaired rails and wagon routes. The enterprising officer also used wagons to bypass destroyed sections of track. Rains’ efforts kept the Confederate armies in the field and made possible every major battle fought from the fall of 1864 through the end of the war east of the Mississippi River.

During this period Rains shipped nearly 100,000 pounds of gunpowder to Richmond where Lee’s besieged army was fighting for its life. The last recorded monthly shipment was as late as January 1865. More Augusta powder almost surely reached Richmond from before and after that date, but those records have been lost. Lee was able to fight to hold Richmond and Petersburg for as long as he did, and then scratch his way west to Appomattox, because Sherman left Augusta standing after July 1864.

Some 400,000 pounds of gunpowder were dispatched to other points in the Confederacy during this period, including North Carolina. The powder and some of the munitions used to defend Wilmington at Fort Fisher, for example, and the powder that made possible the Confederate resistance in the Carolinas under General Johnston, were shipped from Augusta to those locations long after Sherman could have destroyed the mills.

Sherman’s decision to leave Augusta standing from July through September 1864 was, at best, a strategic oversight. His decision to ignore Augusta a second time as he marched without serious opposition for Savannah, however, must be categorized as an egregious eyes-wide-open blunder. His decision to repeat that grand mistake during the last February of the conflict is simply inexplicable. Sherman’s choices lengthened the Civil War and resulted in the deaths and maiming of untold numbers of men on both sides as surely as it extended the suffering of civilians.

In light of Sherman’s orders, the importance of Augusta, and the existence of the powder mill’s ordnance records, it is time to reevaluate the true impact of Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign, his March to the Sea, and the early days of his Carolinas operations on the course of the war.

Both this and the June 2017 article on the powder works are adapted from, Never for Want of Powder: The Confederate Powder Works in Augusta, Georgia, co-authored by Ted Savas.