Civil War soldiers expected to duck bullets and bomb bursts. But Ohioan William W. Richardson discovered that a simple crawling creature could also lay a fighting man low, and even cause a lifetime of torment, when a bug “invaded” his ear during the 1864 Atlanta Campaign.

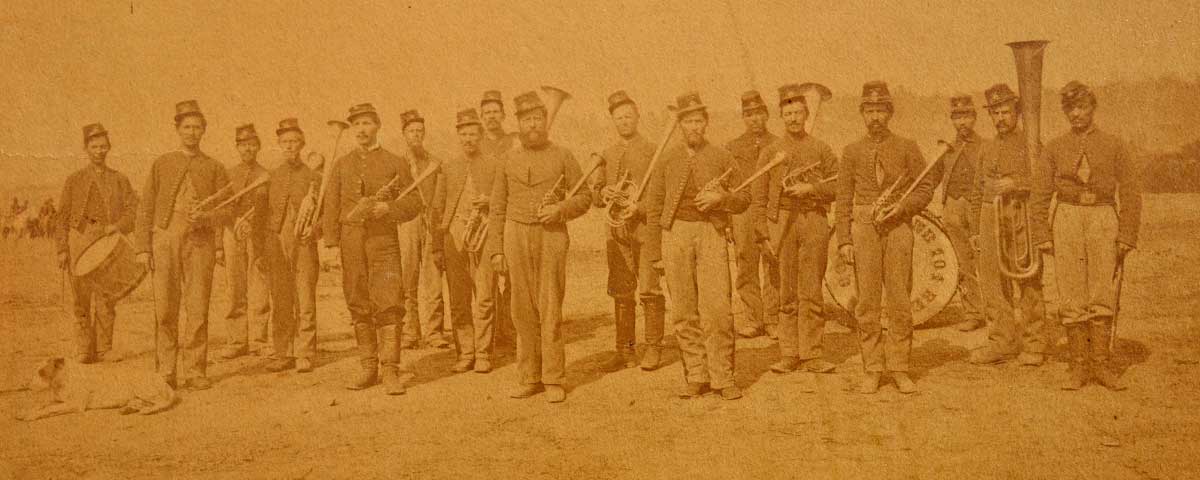

Descendants of Pvt. David Smith,Co.K ,104th Ohio Volunteer Infantry)

Richardson was 34 when he enlisted in the 104th Ohio Infantry on August 11, 1862—an old man to be in the ranks by Civil War standards. He had been a house painter in civilian life, but had also shown some musical ability and was immediately made the drummer of Company I. He held that position until October 1863 when he was detailed as a musician in the 104th’s “Cornet Band.”

That band was a source of pride for the regiment, part of 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, 23rd Corps. Regimental bands were uncommon by the third year of the war, but the 104th kept its musicians for the duration of the conflict. Author Nelson P. Pinney explained in his 1886 History of the 104th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry that while the unit was at Camp Nelson, Ky., in 1862, Colonel James W. Reilly sent for “Professor Dustin Marble, who came all the way from Akron to teach the boys how to make their silver horns talk.” The professor’s tutorial worked, Pinney claimed, and the 104th’s band was “acknowledged to be by far the best band in the corps.”

In November 1864, however, a visiting band from Cleveland sent to entertain the troops challenged that mantle while the 104th was camped near Rome, Ga. In Wild West parlance, the camp wasn’t big enough for all those musicians, and a battle of the bands broke out between the Cleveland boys and those of the 104th and the 112th Illinois that took place within earshot of respective headquarters of Maj. Gens. John Schofield and William T. Sherman. Though the Clevelanders were dressed, according to Pinney, in elaborate uniforms set off with “tinsel and feathers,” the 104th’s band, “dressed in common soldier’s blue,” received the “heaviest applause” and was considered the winner of the three-way melodic maelstrom. The 104th’s band received an invitation to play privately for General Sherman, and from then on could comfortably claim the title as the best band in their corps.

Drummer Richardson made sure anyone who read his four surviving diaries, held in the archives library of the Western Reserve Historical Society (Call # MS. 2136), knew that he was a member of the best band in the 23rd Corps. He neatly inked on the opening pages of each diary:

“Wm. W. Richardson

Cornet Band

104th Reg. O.V.I.

1st Brigade 3 Divis 23 AC

Residence Freedom

Portage County

Ohio”

Richardson wrote fairly lengthy entries, but they cover mostly mundane events. His spelling was often phonetic. He habitually wrote, for example, that his band “plaid” songs for the men. He often mentions carrying a stretcher, and occasionally talks about hauling wounded men to hospitals, as the bandsmen were frequently detailed in such a capacity when they were not entertaining their comrades.

He also had an entrepreneurial streak, and spent some of his free time mending the clothes of his comrades and giving the men haircuts for a small fee. His diaries are full of scribbled tabulations of who owed him for his work, and those enterprising sidelines earned Richardson a mention in Bell I. Wiley’s landmark book, The Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the North. Wiley, however—or more likely the research assistant who collected the information for Wiley—incorrectly wrote Richardson’s middle initial as “D.”

‘Bug still in ear nearly sets me crazy.’

The 104th Ohio spent most of its first year of service guarding railroads in Kentucky, but then took part in Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s East Tennessee Campaign and the Siege of Knoxville in 1863. By spring 1864, the 104th was part of the one-corps Army of the Ohio, one of the three armies Sherman led into Georgia with the goal of capturing Atlanta.

Richardson wrote often during the campaign, but quantity doesn’t always equal quality, and he expended a great deal of ink while remaining frustratingly vague, frequently mentioning “heavy skirmishing” but no significant battle detail. After one stormy day, he did describe an unpleasant scene. (In all of Richardson’s entries, capitalization and punctuation have been edited to enhance readability, but spelling is reprinted as original, without the use of [sic].)

June 7, 1864

Had a very heavy thundershower about noon & we all took a good soaking. The road we traveled was strewn with dead horses & mules heads, hides & [illegible] of the Beef Cattle & the stench was almost suffocating. After the shower the ground was alive with magots washed about by the rain. But the air was much more pure.

Insects, already on the move in the hot, damp Georgia climate, gravitated toward the filth surrounding the marching columns. One of those crawlers wriggled into Richardson’s ear and brought on a battle that he did describe in detail. That incident occurred as Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston was withdrawing the Army of Tennessee from the Kennesaw Mountain line.

June 30, 1864

Cut hair most of the forenoon. Slept on the stretcher last night & rested fine. Was mustered for pay….

July 1, 1864

Camp 10 miles below Maryetta, Ga. weather very fine also hot. Off of duty on account of a bug crawling in my ear during the night. Sent to field Hospitall for relief & Rogers tried in vain to remove it by pouring water & oil in ear. Suffered terribly. 9 PM no better. Reg. ordered to be ready to move at any moment. [Private Volney Rogers of Company I was the only man in the regiment with that surname.]

July 2, 1864

Weather very hot, feeling very bad. Bug still in ear nearly sets me crazy. Dr. does not put anything in to kill it for fear it cant be removed. Got no rest all night. Hard fighting on our right from daylight till 9 AM

July 3, 1864

Weather very warm. Severe headach & no rest. Bug still crawling by spells & nearly sets me crazy. Dr used syringe but only makes it worse. 9 AM nearly crazy & head nearly bursted. General movements of troops. 14th & 17th Corps passed today. Rebs left Kenesaw Mt. today. Regt left this Eve. I was not able to go with it.

July 4, 1864

Cloudy & threatens rain. Band left for the Reg. Heavy cannonading on our right. All Infantry & Artillery on the move. Bug still beating brigade calls in my ear. A rough 4 of July for me. 3 PM captured the c—-d [presumably “cussed”] bug from me ear which is more of a victory for me than to captured all the Greybacks or Johnies in the rebel army. (It was an insect of 6 legs & nearly ¼ inch in length). It was a big 4th of July victory. 8 PM all quiet.

July 5, 1864

…Slept well and feeling quite well except terrible hammering in ear. It also smarts & burns….

July 6, 1864

Reveille at Day break. Marched at 9. Roads blockaded with supply trains. Captured Rebs, Strong fortification. Heavy cannonading along the Chatooche river. Marched over roughly [illegible] Seven miles & camped in woods for the night. 4 PM crossed the RR 7 miles below Marietta. (Ear giving me a good deal of pain & trouble. Has commence to discharge & nearly Deft in it. ) Petersburgh, Va., in our possession.

July 7, 1864

…Went in to camp at 10 AM…weather very hot. Suffering with ear very much….Dr. Says it may cause me to be entirely deft in that ear….

Richardson’s mentions of his ear problems drop off in his extant diaries, and his service record indicates that he was in the ranks during the September capture of Atlanta, and through the rest of the war with his regiment, including the horrific Battle of Franklin on November 30, 1864. Private William Bentley of the 104th recalled that at that battle, Confederates were “jumping over the boys heads” at the section of the earthworks defended by the Buckeyes. Richardson’s stretcher was undoubtedly put to use at that Tennessee harvest of death, as his regiment lost some 60 men, its highest casualty tally during the war.

The musician was discharged with his regiment in 1865, and returned home to Ohio. But he brought a number of army-induced ailments home with him and his ear never truly healed. His pension file in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., is full of surgeon’s certificates and affidavits from neighbors and friends describing his maladies. And while Richardson never specifies in his diaries which ear was afflicted, a number of the pension documents indicate the insect crawled into his left ear. The resulting damage eventually caused that ear to fail, as the affidavit below from fellow Ohioan George Phelps, taken on June 6, 1891, and found in Richardson’s pension files, indicates:

‘Suffering with ear very much… Dr. says it may cause me to be entirely deft in that ear.’

“I was well and personally acquainted with William W. Richardson…from the time he came home from the army until 1870 and saw him each year during this time. When he came home from the army he was suffering with chronic diarrhea, piles and stomach trouble and was weak and emaciated and complained of said diseases. He was also partially deaf which I noticed while talking to him.”

Richardson’s maladies eventually rendered him unable to work as a painter, and he was awarded a veteran’s disability pension. He died on July 27, 1909, and some of the latest-dated documents he penned are written in the shaky hand of a man who is not well. William W. Richardson—drummer, stretcher-bearer, tailor, barber, and victim of a six-legged foe—lies buried in the Fair Street Cemetery in New Philadelphia, Ohio.

Morale Boosters

Regimental bands were a vestige of the prewar militia system and very common in the Union Army when the Civil War began. A May 1861 order allowed every infantry regiment to have its own band. A decree issued by the U.S. Adjutant General in July 1862, however, disbanded all regimental bands, and permitted only brigade bands.

That order was very unpopular, as soothing music helped to restore morale and buoy weary troops when times were rough. A Massachusetts soldier summed up that sentiment when he complained about the directive, “I see the effects of a good band….[I]t scatters the dismal part of camp life, gives new spirit to the men.” The 1862 ban, therefore, was not always strictly enforced. Some shrewd colonels simply reenlisted the bandsmen as members of the rank and file, then “detailed” them to serve as musicians, as Colonel James Reilly did with the cornet band of the 104th Ohio.