Nothing conjures the romance of travel on America’s rivers like the riverboat. Whether by reading the works of Mark Twain or simply watching the musical “Showboat,” we picture the elegantly trimmed snow-white vessel, its smokestacks billowing, whistle blowing, and paddlewheels churning, as the visual representation of the glamour of river travel in the 19th century. After the Civil War’s outset in 1861, however, control of the rivers became vital to Union victory in the West, and a trio of graceful river steamers was modified into inelegant tools for the support of Federal operations. Among those selected to undergo a radical “sea change” was the four-year-old Cincinnati-built commercial steamboat A.O. Tyler. Over the next four years, it would serve Northern forces well, earn distinction for itself and its crew in a number of battles, and end active service in a desperate rescue operation on the Mississippi.

Early in the war, the Union Army and Navy frantically cast about for craft that were suitable for river warfare. These vessels would have to be well-armed, and have the shallow draft required to negotiate the uneven depths of fickle Southern rivers. They also needed a thick outer shielding for protection against enemy fire.

Just two months after the attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861, the Army—with Navy input—paid $62,000 for three sidewheel steamers, including A.O. Tyler. Although the riverboats were built with shallow draft specifically to navigate shoals, and had the capacity to mount artillery, their skin—too thin to withstand shot and shell—required serious modification.

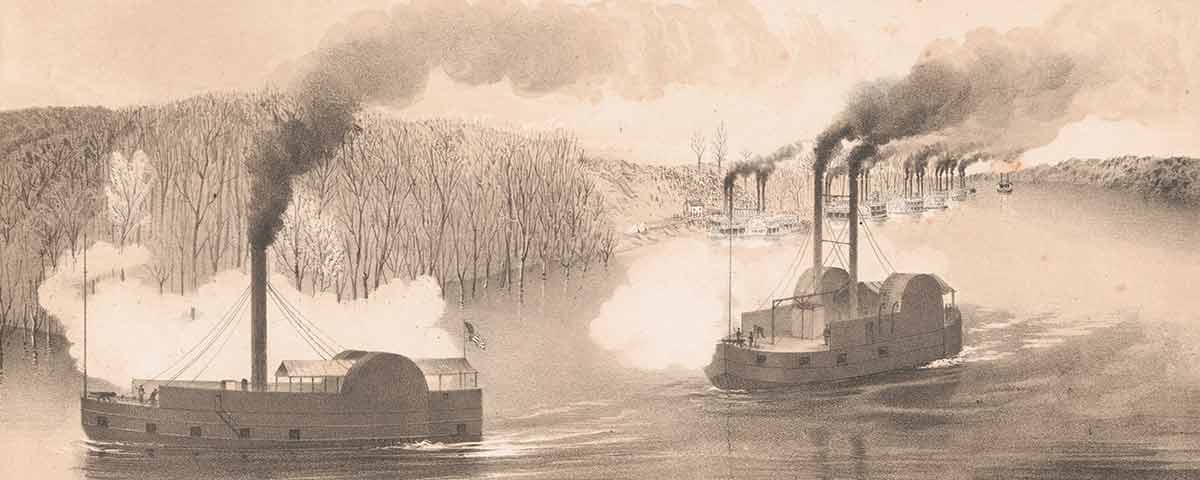

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]There in a Pinch The converted riverboat Tyler, above left during the fighting at Shiloh, proved to be one of Ulysses Grant’s most reliable and valuable assets throughout the war.[/quote]

Along with its sister vessels, Tyler was re-conformed as a Federal gunship. Six 8-inch guns and a 32-pounder were mounted, the engines and boiler were retrofitted, and the entire boat was sheathed in 5-inch-thick white oak planks. The modifications did nothing for its looks—the vessel was variously described as a “wood crate” and a “clumsy barge”—but afforded some protection from Confederate fire. Its armaments delivered significant firepower.

Tyler was the largest of the three so-called “timberclads.” After the retrofitting, it ran 180 feet in length, with a 45-foot beam, and drew 6 feet of water. Although it weighed around 575 tons, its two high-pressure steam engines helped it achieve speeds up to 8 knots, not inconsiderable. By late August, Tyler was pronounced combat-ready as a member of the newly formed Western Gunboat Flotilla, the so-called brown-water force operating on the Western rivers. Tyler steamed to Cairo, Ill., at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, where it deployed along with fellow timberclads Conestoga and Lexington to support Union reconnaissance operations.

Almost immediately, Tyler saw action. Off Hickman, Ky., on September 4, 1861, it and Lexington engaged CSS Jackson, a side-wheel river tug retrofitted for service in the Confederate Navy. During the brief and inconclusive exchange, the two Union timberclads found themselves under fire from Rebel shore batteries as well as Jackson, and withdrew.

Two months later, when Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant attempted to wrest Belmont, Mo., from Rebel hands, Tyler was one of two gunboats that supported the assault, firing consistently at the enemy, and covering the withdrawal of Grant’s troops. Although this attempt failed, Grant recognized the value of timberclads in amphibious operations.

Over the next several months, Tyler participated in operations on the Upper Mississippi, Ohio, Tennessee, and Cumberland rivers, playing a significant role in helping capture Confederate Forts Henry and Donelson. It was in early April 1862, however, that the gunboat performed its greatest service to Grant. Along with Lexington, Tyler successfully protected Grant’s flank at Pittsburg Landing, Tenn., during the Battle of Shiloh. When Rebel troops attempted to anchor their right flank at the river, the timberclads’ intense all-night barrage drove them back, enabling Union forces to mount a successful advance. After the battle, Grant acknowledged that his victory was in large part “due to the presence of the gunboats.”

In mid-June, Tyler—in the company of two other vessels—was attacked by the Rebel ironclad Arkansas on the Yazoo River near Vicksburg, Miss. After one of the Union ships was disabled and the other fled for the safety of the Federal fleet, Tyler was left to fight Arkansas on its own—an unequal battle, in the ironclad’s favor, from the start. Tyler’s shells simply bounced off the Rebel craft’s thick railroad-iron sides. The wooden-sheathed Tyler, in return, was severely damaged, but finally managed to escape, injured but intact.

Along with the rest of the squadron, Tyler was transferred to the Navy in October 1862, and three 30-pounder Parrott guns were added. Shortly, it mounted another four 24-pounders, and for landing duty, a 12-pounder howitzer, making it the most heavily armed timberclad of the war.

Tyler participated in the siege and eventual capture of Vicksburg, Miss., and was instrumental in opening up Arkansas to Union invasion. It patrolled the lower Mississippi and White rivers for the duration of the conflict, exchanging fire with Confederate batteries on several occasions.

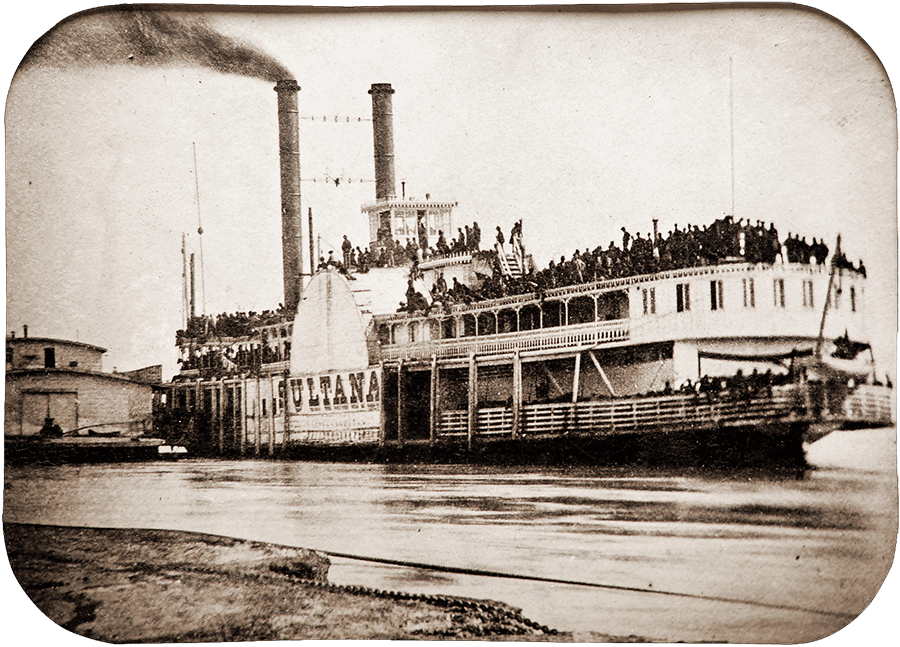

On April 27, 1865, Tyler participated in rescuing survivors after boilers on the river steamer Sultana exploded near Memphis, Tenn. Of 2,500 passengers, most of them recently released Union POWs, only about 550 survived.

In August 1865, the Navy sold off Tyler, along with most of the Mississippi Squadron’s vessels. According to the Hampton Roads Maritime Museum, “For all practical purposes the Tyler and her timberclad sisters were limited ersatz warships built in a period of emergency. With many river miles and battles recorded in the logbook, the Tyler turned out a rather useful warship despite this.”

Ron Soodalter, a regular contributor to America’s Civil War, is the author of Hanging Captain Gordon.