Access to safe drinking water has been a major concern for sailors throughout mankind’s conquest of the oceans. Ships normally carried potable water in casks or tanks; however, there was a limit on how long it could be stored in that manner before it became virtually undrinkable. While ocean voyages were generally planned with several landfalls, there are countless accounts of vessels running out of water or having to ration their supplies for days until they reached land or it rained hard enough to catch water.

During the so-called Age of Sail, attempts to develop a means to produce drinking water on-board ship were mostly unsuccessful. Usually only limited quantities could be produced in stills in the ships’ galleys. It was not until the advent of steam propulsion in the early 19th century that a possible solution to this dilemma appeared. Volumes of steam from the ships’ boilers could now power a distilling apparatus that was capable of producing large quantities of potable water.

The introduction of steamships presented additional problems, as fresh water was needed to operate the boilers to produce steam. The paddle-wheeler USS Missouri was launched in 1841 as one of the Navy’s first steam-powered ships. Missouri had two 40-ton water tanks installed to provide water for both the boilers and crew. Missouri’s sister ship, USS Mississippi, served as the flagship for U.S. Navy operations along the Gulf Coast during the Mexican War and had to return to Port Isabel (Texas) twice for additional water.

By the Civil War, condensers had been developed and installed on warships, altering their operational capacity. CSS Alabama and USS Kearsarge, which clashed memorably off the coast of France in June 1864, are prime examples of benefactors of this new technology.

Captain Raphael Semmes wrote of Alabama: “The vessel was very light, compared with vessels of her class in the federal navy, but this was scarcely a disadvantage, as [it] was purchased as a scourge of the enemy’s commerce rather than for battle….She had a 300 horsepower engine and a condenser to provide fresh water for the crew.” Alabama remained at sea for 534 of 657 days of its time in commission. The ability to produce fresh water was critical, since its tanks could hold only an eight-day supply.

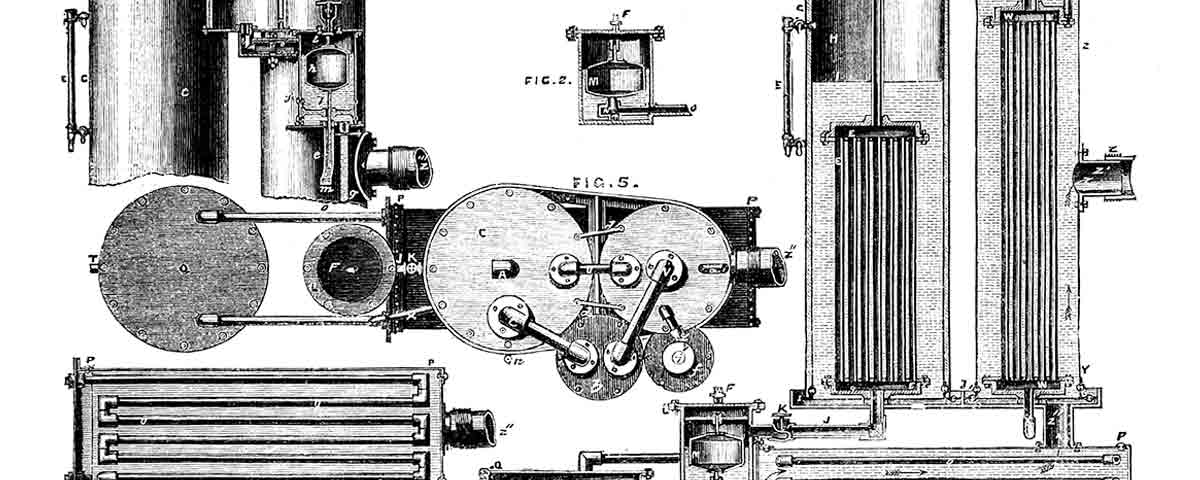

It is likely that the apparatus used on Alabama, known as a jet condenser, was one invented by French chemist Alphonse René le Mire de Normandy. The apparatus (shown on the opposing page) had three principal parts: an evaporator, a condenser, and a “refrigerator” or cooler. Steam from the boiler, which was under pressure and at a temperature exceeding the boiling point of atmospheric seawater, flowed through tubes surrounded by seawater in the evaporator. The seawater was heated to boiling and the resultant salt-free steam vapor flowed through tubes in the condenser that were surrounded by seawater. The output was distilled water. Normandy cleverly designed his system so the output of the evaporator absorbed enough air to improve its taste. The fresh water from the condenser flowed through the “refrigerator,” where it was cooled by seawater and then through a charcoal

filter to the ship’s tanks. [The jet condenser used by the famed Union ironclad Monitor is conserved at The Mariners’ Museum and Park in Newport News, Va.]

Alabama’s ability to stay at sea for extended cruises is proof the apparatus worked. It did, however, require maintenance. Semmes recorded in August 1862, “[O]ur fresh water condenser is about giving out, the last supply of water being so salt as to be scarcely drinkable.” He likely had it repaired during a retrofit–resupply stop in Cape Town, South Africa.

The introduction in the 1860s of surface condensers, which kept cooling seawater and exhaust steam separate, was another critical advance. In a surface condenser, cooling seawater flowed through tubes in the condenser casing. Exhaust steam from the engine flowed over the tubes, was condensed, and then pumped back as relatively pure water to the boiler. The elimination of salt reduced fouling of the boilers and permitted use of higher operating steam pressure. The use of the surface condenser brought with it the need for pure make-up feed water for the boiler (i.e., lost water could not be replaced by seawater, as in the past). This led to additional makers of suitable distillation equipment.

The mayhem Alabama caused on the world’s oceans—principally to Union shipping—over 22 months depended on its ability to access food, supplies, and potable water. It obtained much of the food and supplies from the ships it captured, but it was the shipboard production of drinking water that gave it

the flexibility to stay at sea for extended stretches. Alabama’s storied career was possible only by the development of the salt-to-fresh-water conversion systems described here. By the end of the Civil War, potable water production using such condensers had become commonplace, found aboard ships of every type.

John V. Quarstein is the director emeritus at the USS Monitor Center in Newport News, Va. Gerry S. Hanley is a retired naval architect and nuclear engineer based in Williamsburg, Va.