A Norwegian immigrant wrote letters home in his native language and invisible ink

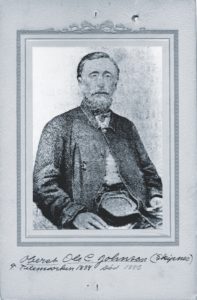

Ole C. Johnson was born on February 23, 1838, in the Telemark region of Norway and immigrated to the United States when six years old. His family settled in Wisconsin and he was working as a teacher in Stoughton at the outbreak of the Civil War. On November 12, 1861, the 23-year-old was commissioned a captain, and took command of Company B the following month. His company joined the newly formed 15th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment, mustering in in Madison on February 14, 1862, for three years service. He would eventually rise to the rank of colonel and command the 15th.

Ole Johnson put his life on the line for his new country. (Wisconsin Historical Society)

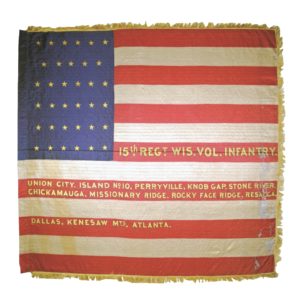

Composed almost entirely of Norwegian immigrants, the 15th Wisconsin was nicknamed the “Scandinavian Regiment.” While the regiment was passing through Chicago on its way to St. Louis, the Scandinavian “Society Nora” presented it with a silk flag, featuring the U.S. national colors with American and Norwegian arms and the motto “For Gud og Vort Land!”(“For God and Our Country!”) painted on the canton.

They were attached to the Army of the Mississippi until April 1862, during which time they fought at the Battle of Island No. 10. Following the U.S. victory there, they helped garrison the island until the were reassigned to the Army of the Mississippi in July 1862, the to the Army of the Ohio. in September. They became part of Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck’s forces occupying Corinth following its capture, then participated in the Kentucky Campaign, culminating in the Battle of Perryville.

The following letters by Johnson begin immediately after that fight, and continue through the Battle of Chickamauga, where he was captured. The resourceful soldier used his ethnicity to his advantage, writing letters home in his native tongues to befuddle his Confederate guards. He even resorted to chicanery, and penned portions of his letters in invisible ink, instructing recipients as to how to make the writing visible. Johnson’s letters are held in the collection of The Wisconsin Historical Society Archives, Madison, Wisc.

[hr]

Near Perryville, Ky.

October 10, 1862

DEAR BROTHER,

Long before this reaches you you will have read the news of the battle in this vicinity day before yesterday. I understand that McCook’s Corps and Sheridan’s division of our Corps suffered the most. One brigade of our division was ordered to the support of Sheridan and suffered severely. We were near the right to watch any movement the enemy might make to flank us. They advanced for that purpose but retreated precipitately when we advanced to meet them.

We chased them at double quick through the fields and over fences for about a mile and a half when we halted and the battery (the 9th Minn) opened upon them. They retreated through Perryville and formed on the other side where their battery replied to ours. The artillery fire was kept up for about an hour when it ceased and we retired about a mile and rested for the night which is attributed to our having broken their lines on their left and were in a position to outflank them and cut off the retreat. Both armies have suffered severely considering the time we fought and the losses I suppose can only be ascertained by the official reports. When we will get hold of Bragg again is hard to tell but I hope very soon so we can clear the soil of Ky of traitors. One rebel was taken prisoner here who had two paroles in his pocket. He was immediately sent out and shot by order of Gen. McCook….

In November 1862, the 15th Wisconsin Infantry became part of the newly formed Army of the Cumberland, in which they served in various brigades, divisions, and corps for the next

two years. Johnson was promoted to major on November 15, 1862, following the previous major’s resignation. His regiment fought at the Battle of Stones River and spent the rest of the winter and early spring near Murfreesboro, Tenn.

[hr]

Camp near Murfreesboro, Tenn.

January 14, 1863

DEAR BROTHER,

…Many of the reg’t have been unwell as a consequence of the hardships and exposures to which they were subject during the fight….

There are hardly any citizens left in Murfreesboro. They fully expected to whip us there and the citizens made no concealment of their secession sentiments but when we were victorious they thought it would be safest to clear out. I don’t know that I should like anything better than to see that place laid in ashes.

I agree with you in what you say about the closing of the war by the 1st of June. Still if foreign powers would keep aloof perhaps we might go on even after that for we could keep their ports blockaded and keep advancing slowly also by land and in time the rebels would get disheartened and give up the contest. I do not believe they will fight any more for Tenn., Ky have given that up, and Tenn. and Ky. troops will fight with but little zest hereafter. They fought like tigers in the late battle as we can bear ample witness….

Upon the death of Lt. Col. David McKee, Johnson was promoted to that rank from February 26, 1863. He took command of the 15th Wisconsin in May, when Colonel Hans Christian Heg was promoted to command a brigade. Several months later, during the brief but effective Tullahoma Campaign, the 15th Wisconsin helped push Confederates out of central Tennessee.

[hr]

Near Manchester, Tenn.

June 30, 1863

DEAR BROTHER,

It is of course known to you before this that we have commenced our forward movement. We left Murfreesboro the 24th and came the night before last.

The rebels made quite a determined stand in some of the “gaps” the two first days but since that they have made no opposition whatever. Tullahoma is 12 miles from this place nearly due west and our forces are reported to occupy it but I do not know if that is true but it is pretty certain the rebels will make no stand there. The country we have passed over is very hilly and it has rained every day since we left Murfreesboro rendering it very difficult for the artillery and baggage wagons to move. Now we are literally “stuck in the mud” and I believe it will be an impossibility to move until we have a day or two of good weather. It is very unfortunate that we should have such a rain at such a time for it is evident that Rosecrans intended to push right on to Chattanooga but I presume he will be compelled to abandon that purpose as the rebels will have so much time to prepare. They were evidently taken by surprise and not prepared for our coming or they would have made our way a great deal harder through several “gaps” that we had to pass and which were very easily defended. At least so prisoners say. Our Brigade has not been engaged….

[hr]

Head Qrs. 15th Wis. Vol., Winchester, Tenn.

July 7, 1863

DEAR BROTHER,

As I expected when I last wrote to you Bragg did not fight at Tullahoma though after I had sent the letter I felt appearances changed and a battle was generally expected. Our corps was ordered into position four miles from Tullahoma but before we got that near our cavalry was in the place and we marched through it that night. They had undoubtedly left in great hurry and abandoned many things among which I believe were all the tents of the army which had been packed up and stored for the summer some time ago. They also had to leave some siege guns and corn meal which last came very handy as we were short of rations. We came right on to this place here it seems likely we shall stay for some time at least until the rail road is put in order which will not be long.

Our whole cavalry force went out yesterday, probably down into Ala. and Geo. and the vicinity of Chattanooga.

If the heavy rains had not hindered us I think Bragg would have been compelled to fight for he would not be able to get away….

Throughout most of 1863, the 15th Wisconsin was assigned to the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, 20th Army Corps. On the second day of the Battle of Chickamauga, during Longstreet’s Breakthrough, the regiment was mistakenly fired upon by U.S. as well as Confederate troops, suffering a 63 percent casualty rate. Johnson was taken prisoner and surrendered his sword to a Confederate officer he thought was on the staff to Maj. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman. It was more likely Lt. Col. G. Moxley Sorrel, staff officer to Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, as he later owned the sword and carried it as his own for the rest of the war. Johnson was sent to Libby Prison in Richmond. To circumvent prison authorities, he sometimes wrote letters home in Norwegian or invisible ink.

[hr]

Libby Prison, Richmond, Va.

November 15, 1863

DEAR BRO,

I received your letter of the 2nd inst. yesterday and also the box of books. I can now make my time endurable. I was lucky enough to borrow a German grammar which I have been studying. I am sorry you did not send me some northern papers. I should have liked very much to have some “State Journals” so as to learn the home news, and other papers. I perceive you have not received my first letter. I wrote to you about the last of Sept. and gave a list of prisoners from our reg’t as far as I know them to have it published in the “Emmigranten.” I sent it also to the reg’t where it is doubtless received before this time and those anxious to know will have to enquire there. Twenty five came up with me a list of whom I sent. Nine have come up since that I have heard of but could not get their names, beside the hospital steward and four nurses. This makes thirty nine (39) enlisted men and Capt. Gustavson and myself. There may be more….

My love to you all.

Ole

[hr]

[different handwriting follows:]

On board the Adelair

November 26, 1863

PS Heat your letters hereafter and you may learn more from them than at first appears.

S B Hawley

[hr]

Libby Prison, Richmond, Va.

December 7, 1863

DEAR BROTHER,

…Our Congress is meeting today and I would think it will do something to get us exchanged. Many have now been here since May and many more since June and July, and they are naturally eager to get out….

[in invisible ink]

When we were taken prisoner, many of us were collected and taken back to the Chickamauga River by a captain in General Hindman’s staff who, by the way, was a gentleman. He showed no desire for revenge and did not allow the soldiers to take the canteens and haversacks from the prisoners, as some attempted to do….I think you will find that the general opinion of everyone who has been a prisoner is that they have only been mistreated by those who were left behind on the garrison towns and camps and don’t know anything about the trials and dangers of a soldier’s life, and by the home guard, which is thoroughly despised by every prisoner. If a prisoner is mistreated and robbed on the battlefield, then it is generally by the stragglers in the rear who, one way or another, slip out of the lines on the march to the front. The man who goes bravely into battle is never guilty of such a cowardly deed.

From the Chickamauga River we were taken some two or three miles farther toward the rear troops, where we found those who had been captured on Saturday, and at four o’clock we were started on the road to Ringgold, a distance of 12 miles, where—we were told—we would stop overnight and get something to eat….At nine o’clock in the evening we came to Ringgold, tired and hungry, and got the news that we had to go four more miles before we could get rations and start on the train to Atlanta. At 11 o’clock we arrived at a railway station, which I have forgotten the name of, and got permission to light a fire, but the night was cold, and we got only a little rest and less sleep. The next morning we were given the unwelcome news that we had to go another four miles on foot before we could get something to eat. We started at eight o’clock and arrived at Tunnel Hill at 10 o’clock, and one unit was immediately put to work baking some cornbread. But before it was ready we were put on board a train and set out for Atlanta….If it hadn’t been for the fact that some of the prisoners had some rations with them when they were captured, which they were willing to share with me, I would certainly have starved, and I know there were many who suffered from the pangs of hunger. I am forced to stop here, since I cannot see my writing…. Write to me in the same way—with onion juice or soda dissolved in water….

[hr]

Libby Prison, Richmond, Va.

December 10, 1863

DEAR BROTHER,

…We arrived in Atlanta Tuesday evening at sundown and were marched through the streets of the city to its eastern side—as I believe. In the evening we received a half a loaf of bread each, but there wasn’t enough to go around, and my people and I were among those who got nothing. Wednesday morning one loaf of bread was passed out per man, for the first time I got something to eat from the Rebel authorities. Wednesday afternoon we were marched into some barracks and examined, and the enlisted men had their blankets and overcoats taken away, as well as pocket knives and other small things….

Thursday morning we were marched through the city to the station…we received a day’s ration of bread and five-days’ ration of smoked bacon. The next rations we received were in Radleigh [sic], North Carolina—a day’s ration of crackers—and a further day’s ration of crackers at Weldon on Monday morning. We saw demonstrable signs of sympathy for the Union almost everywhere along this route, but especially in North Carolina….In some places the citizens seemed disposed to ridicule and insult us, but in general we were treated with respect…..Only a few men spoke to us in an impolite manner, and these always got the worst of it because we had permission to use our tongues in self-defense, and the guards chuckled when they heard how we ridiculed them for their courage in staying at home….Thursday evening, the 29th, we arrived at Libby….

[hr]

Libby Prison, Richmond, Va.

January 15, 1864

DEAR BRO,

I received your letter of Dec. 21st answered it immediately but since that there has been no Truce boat until yesterday. Still you will probably receive that before you do this. We have once more hopes of a speedy exchange since communication is again opened and I sincerely hope we shall not this time be disappointed. During the interruption of communication we have been very lonesome for we have not only rec’d no mail but the usual extracts from Northern papers in the morning papers here have been wanting and that you can well imagine forms one of the chief attractions with us. Col. Ould is now at City Point conferring with our Commissioner and I hope no small petty quarrel or personal considerations will come up to once more blast our hopes. Affairs move as usual here. Gen. Morgan is at present and has for some time been the lion of the city. He together with Gen. A. P. Hill and others visited the prison. Since that time we have had a sufficiency of wood for cooking purposes, which we had not before, and for which we feel inclined to thank them. Goodbye.

[hr]

Libby Prison, Richmond, Va.

February 14, 1864

DEAR BROTHER,

I have received no letter from you later than Jan. 4th. I suppose the authorities here thought it might be a little comfort to us to write home when we pleased so they have limited us to one letter per week and that must contain only six lines.

Nor do they issue our boxes. But as the old saying is “Every dog has his day.” Ours will come sometime I hope. Why does our gov’t continue to send boxes when the authorities here will not distribute them? Our living is not of the fattest but they have not made out to starve us to death yet. Love to all.

[hr]

[In Swedish, Danish, and Norwegian]

Libby Prison, Richmond, Va.

February 21, 1864

DEAR BROTHER,

Send me in your next letter a ten-note bill if you can do it without it being discovered here. I think you can in one way or another glue it to a photograph. If that isn’t possible, Karen can send me some kind of memento [?] sewn with thick paper and put the money in there. Such things usually can pass. If you hear that I have gotten out of here, don’t send anything.

In spring 1864, Confederate authorities began transferring Libby Prison inmates to other prisons farther south. By mid-May, Johnson was aboard a train near Chester, S.C., when he and two officers of the 2nd East Tennessee Infantry escaped through a hole in the floor of their boxcar. They lay beneath the moving cars until the train had passed over them. They traveled through swamps and over mountains, seeking assistance from enslaved people and Union sympathizers as they avoided Confederate soldiers and potential informers. About one month later, they finally reached a U.S. fort outside Strawberry Plains, Tenn., having traveled more than 200 miles.

Johnson traveled back to Wisconsin to see his family, but rejoined his regiment near Atlanta on July 24, 1864.

The 15th Wisconsin fought in several battles in the Atlanta Campaign and in November 1864 were transferred to the Department of the Cumberland. They were mustered out of service between December 1, 1864, and February 13, 1865. Ninety-four of its men lost their lives fighting in numerous major Western Theater battles, while another 242 died of disease.

Johnson became colonel of the 53rd Wisconsin Infantry on February 21, 1865, but the war ended before they ever took the field. He settled in Beloit and became a businessman. On January 3, 1867, he married Caroline Freie Bødtker and they had one son, Wilford Chickamauga Shipnes(s). Johnson was twice elected mayor of his new hometown and in 1871 was appointed Immigration Commissioner of Wisconsin. Late in life, Johnson changed his surname to “Shipnes,” the name of his family farm in Norway. He died in Beloit on November 4, 1886.

Catherine M. Wright was curator at the American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Va., from 2008-2019, and the principal researcher and writer for the museum’s permanent exhibition, A People’s Contest: Struggles for Nation and Freedom in Civil War America. She currently resides in Edinburgh, Scotland.

This story appeared in the April 2020 issue of Civil War Times.