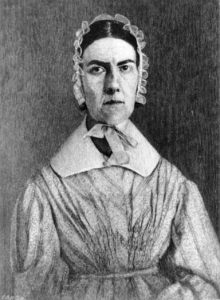

Angelina Grimke was like a meteor flashing across the 19th-century sky. Few individuals were more historically consequential. In her life and work, Grimke brought together the two great human rights issues the United States faced in the 19th century: slavery and women’s rights. Born in Charleston, S.C., the daughter of John Grimke, a planter, slaveholder, lawyer and politician, she burst into public life in 1835 with a small article published in William Lloyd Garrison’s radical newspaper The Liberator. She endured a period of controversy and personal danger in consequence of her public advocacy on behalf of enslaved people, and, as a result, put the issue of women’s rights publicly on the agenda for the first time in American history.

In 1835, already a member of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, and horrified at the violent attacks on abolitionist meetings and proponents, Grimke wrote a letter to Garrison expressing her solidarity with him. It was supposed to be a private letter, but he published it in The Liberator using her name. It was probably irresistible to Garrison. She was, after all, a Southern woman, the daughter of a slaveholder. Her Quaker friends and leaders urged her to withdraw it. Instead she leaned in.

Within the year Grimke took up an invitation to become a speaker for the American Anti-Slavery Society, becoming the first woman to go out on the antislavery lecture circuit. Then the real controversy began, the one that would join the cause of slaves and of women in a fateful historical conjuncture. Between 1836 and 1837, Grimke toured the country speaking on behalf of slaves. She was an incredible addition to the antislavery cause, offering powerful first-person testimony to the horrors of slavery. Hundreds came to hear her speak, men and women, “colored” and white.

The backlash was fearsome. No respectable woman should speak to “promiscuous” (that is, sexually mixed) audiences. She was denounced; her life was threatened. She did not waver: “Now that my master [i.e., God] has burst my fetters and set me free, I never expect to suffer myself to be manacled again.” The bondage imagery was pregnant with meaning. Who, exactly, was she talking about? The idea of the slavery of gender was born.

In the summer of 1837, Angelina Grimke was denounced from the pulpit of just about every Congregational church in the United States. Through – out the tour she had quietly emphasized the point that to be effective in the cause of the slaves, antislavery women had to throw off social constraints and injunctions to keep silent. Now under assault, Grimke went further and, aided by her sister Sarah and against the advice of all her mentors, tackled the issue head on, defending her right to speak and act in public in a series of published letters to Catherine Beecher, another female public figure—but one with far more conventional ideas of women’s sphere.

Grimke published 13 letters to Beecher in 1837, including one in which she insisted (as the title clearly conveys) that “The Sphere of Woman and Man as Moral Beings [is] the Same.” And another, “Human Rights [are] not Founded on Sex.”

“The investigation of the rights of the slave has led me to a better understanding of my own,” Grimke wrote. It seems hopelessly modern, and perhaps you won’t believe me, but in 1837 she said this “truth will be self-evident, that whatever it is morally right for a man to do, it is morally right for a woman to do….Now, I believe it is woman’s right to have a voice in all the laws and regulations by which she is to be governed…and that the present arrangements of society…are a violation of human rights, a rank usurpation of power, a violent seizure and confiscation of what is sacredly and inalienably hers…woman has just as much right to sit in solemn counsel in Conventions, Conferences, Associations and General Assemblies as man—just as much right to sit upon the throne of England, or in the Presidential chair of the United States.” Is she not incredible?

From 1835 to 1838, she led a remarkable public life. She was fearless. Then, after a singular courtship with Theodore Dwight Weld, a radical abolitionist—in which they openly discussed what a partnership of equals would be—they were wed in 1838, with vows in which she promised to love and honor but, conspicuously, not to obey. That was effectively the end of her public career. Despite Angelina Grimke Weld’s best efforts, marriage, motherhood and some version of domesticity bowed even her. She would teach, and would participate in the huge drive during the Civil War to collect 1 million signatures on a petition to Congress for an amendment ending slavery; she would lend her name to women’s suffrage organizations and live a life of principle and commitment to the causes of antislavery, women’s rights and human rights. She would reappear here and there, including at the founding meeting of the Woman’s Loyal National League, where she spoke as a representative of South Carolina. In 1870 she participated in a women’s suffrage protest by casting a vote in an election.

But when Elizabeth Cady Stanton and other women met in Seneca Falls, N.Y., in 1848 to write “The Declaration of Sentiments”—the foundational document of the American women’s rights movement—Angelina Grimke Weld was there in spirit only. She had three children, and was employed as a teacher to help support them. She would appear only momentarily in the public record thereafter.

Although her meteoric light was dimmed later in life, the brilliant Angelina Grimke Weld did leave a lasting trail.

Stephanie McCurry is a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania and author of award-winning Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South.

Originally published in the January 2014 issue of America’s Civil War. To subscribe, click here.