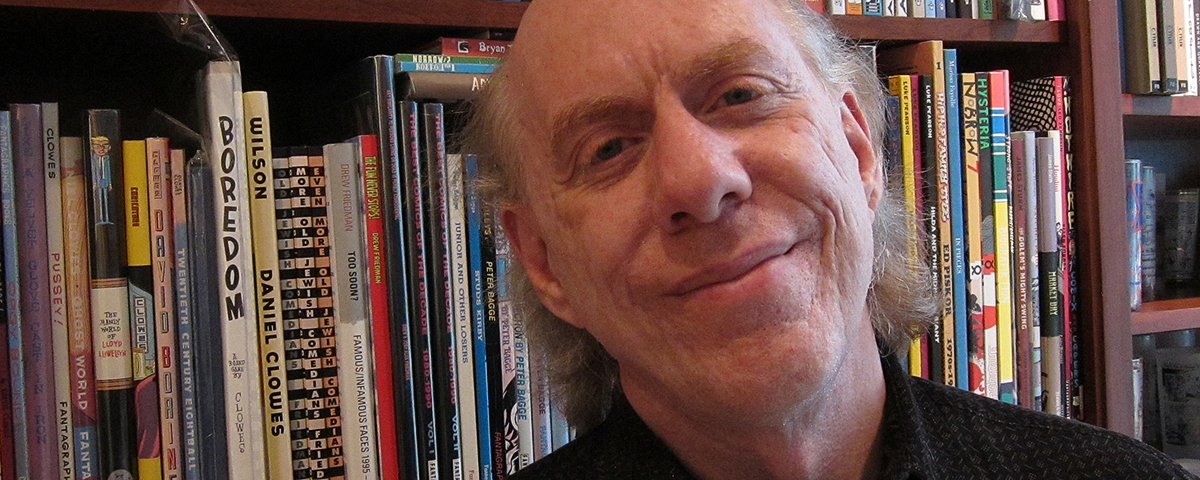

Warren Bernard, an avid collector and longtime lecturer on the history of editorial-political cartoons, recently published Cartoons for Victory (Fantagraphics, Seattle, $34.99, 2015), a history and showcase of the works of cartoonists who lent their talents to support efforts on the American home front during World War II. Former Sen. Bob Dole, 92, a wounded U.S. Army veteran of the 1943–45 Italian campaign, wrote the introduction. Many of the cartoons come from Bernard’s own collection, amassed over years of research through private collections and public archives. The works were rendered by such popular artists as Walt Disney, Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss), Charles Addams (The Addams Family) and Harold Gray (Little Orphan Annie) and include such iconic American characters as Superman and Mickey Mouse. Bernard has spoken at the Library of Congress and the Center for Cartoon Studies, among other venues. Military History spoke with him about his collection, his new book and the power of cartoons to shape wartime opinion.

What sparked your interest in editorial-political cartoons?

What sparked your interest in editorial-political cartoons?

While in high school I read comic books and strips, of which Doonesbury was my favorite. That lead me to Jules Feiffer and other political cartoonists of the time like Pat Oliphant and Herblock. Once I had engaged with political cartoons of the day, it was not a far leap for me to look at the political cartoons of World War II. For a time my college major was history with a focus on that war. This then led me to the Great War and the amazing work of European cartoonists.

How extensive is your collection?

It encompasses more than 500 volumes of political cartoon books from the late 1890s to the present. There are more than 50 bound volumes of magazines that contain political cartoons from Germany, Britain, France, the Netherlands, Italy and the United States. The collection covers the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

It also includes more than 60 scrapbooks comprising thousands of never reprinted and difficult to find American political cartoons from World War II. Every day during the war people cut them from the newspapers, and such scrapbooks are a treasure trove of cartoons and information.

When did editorial-political cartooning become an influential medium?

It came into its own with the works of William Hogarth and James Gillray in 18th-century London. Cheap prints of their work were sold on the city streets, and by the late 1790s Parliament had recognized the influence of such prints/cartoons on public opinion.

What were the earliest known war cartoons?

In the 16th century Hans Holbein and Albrecht Dürer drew illustrations about war that are considered forerunners of the modern war cartoon. In terms of a specific conflict, one of the earliest to feature illustrated broadsides was the 1618–48 Thirty Years’ War. In the United States the first acknowledged political cartoon was Benjamin Franklin’s “Join or Die,” used to try to unite the colonies during the French and Indian War as well as the run-up to the American Revolution.

Do you have a favorite wartime cartoonist?

Without doubt the great David Low, of the London Evening Standard—considered the greatest British cartoonist of the 20th century. He spotted the evils of Adolf Hitler early on and was relentless in his casting of the Nazis as evil. He drew some of the most iconic cartoons of the period, including hard-hitting anti-isolationist cartoons in America.

Had any of your relatives served in the military?

During World War II my uncle served in Tehran, running supplies up to the Russians, and my cousin flew the Hump from India to China as a C-47 pilot. My dad was in the Navy from 1946–48 at Pearl Harbor and was responsible for the inventory of equipment and material being returned from all over the Pacific. I also had a great uncle who saw combat in World War I.

How effective are cartoons in shaping wartime public opinion?

The history of the United States is full of examples in which cartoons played a big part in mobilizing support for war.

During the Civil War Thomas Nast’s cartoons in Harper’s Weekly, especially his Christmas cartoons, put a bright light on the sacrifice of soldiers. President Abraham Lincoln called Nast “the best recruiting sergeant the Union ever had.”

In the 1890s newly developed color Sunday cartoons in the newspapers of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer drummed up support for what became the Spanish-American War and gave us the term “yellow journalism,” for the color of Hearst’s comic character the Yellow Kid.

In World War I the Woodrow Wilson administration created the Committee on Public Information to influence the American public’s view of the war, with a separate cartoon division that sent out ideas for the nation’s cartoonists to incorporate. During World War II the War Bond Division of the Treasury Department syndicated its own cartoons about war bond drives to the nation’s newspapers, while the Office of War Information had cartoonists create syndicated works on such topics as rationing, scrap drives and women in the armed forces.

In neither world war, as a rule, did the nation’s political cartoonists criticize the war itself. But the Vietnam era brought a different tone to the political cartoon world, as a number of prominent cartoonists—such as the widely syndicated, Pulitzer Prize–winning Herblock—did not support the war.

‘Men in combat need to find ways to cheer themselves up, and the easiest way is to make fun of the deadly circumstances surrounding their dire circumstances. Cartoonists caught on to this’

What is it about gallows humor that speaks to us?

Men in combat need to find ways to cheer themselves up, and the easiest way is to make fun of the deadly circumstances surrounding their dire circumstances. Cartoonists caught on to this, so it is no surprise that the two most famous cartoonists who made extensive use of gallows humor were soldiers—namely, Captain Bruce Bairnsfather of the British army, and Sergeant Bill Mauldin of the U.S. Army.

Bairnsfather’s use of gallows humor in World War I with his two frontline protagonists—Bert and Alf—was echoed in World War II by Mauldin’s popular Willie and Joe. But in Mauldin’s case the approach was seen as detrimental to the troops, with no less than Generals George Patton and Theodore Roosevelt Jr. complaining about his cartoons. It took Ike himself to clear the way for Willie and Joe to continue their gallows humor ways.

What makes a cartoon powerful and effective?

Cartoons derive their emotional power by conveying any combination of hatred, patriotism, pride, caricature, demonization of the enemy and pity for those suffering.

Where is the line between satire and propaganda?

Satire is but one method used in visual propaganda campaigns. Demonizing the enemy, gross caricature and parody are also used as propaganda tools. These methods can be combined in the same image to enhance the propaganda message.

What role has demonization played in rallying Americans?

There has not yet been a war in which the United States has fought that did not in some way generate cartoons stereotyping the enemy. From the barbaric Spanish oppressing the people of Cuba, to the Pickelhaube-wearing Germans committing atrocities in France and Belgium, to the demon-fanged Japanese barbarians killing American POWs, to the duplicitous North Vietnamese, to the again barbaric Saddam Hussein and Islamic State—stereotypes have pervaded the history of political cartoons during wartime because of the raw emotions they instill in the reader.

Have wartime cartoonists largely pushed their own political ideologies?

Yes, cartoonists often pushed their own political views, such as Herblock and his successor at The Washington Post, Tom Toles. But at many other papers the political cartoonist was at the behest of the publisher and/or editor—for example, Winsor McCay, who worked more than 20 years for William Randolph Hearst’s famed editor Arthur Brisbane. Brisbane gave McCay specific assignments for the editorial page cartoons.

Today, however, many political cartoonists are not tied to a specific newspaper and do not have an editor looking over their shoulder and worrying about circulation. They may have their work syndicated, or they may be online only, so they are free to push any ideology they want.

Have any faced violent reaction to their work, à la Charlie Hebdo?

In recent years political cartoonists from Iran, Turkey, Malaysia and other countries have been sent to jail for their political cartoons. Ali Ferzat, a Syrian cartoonist, was beaten up for criticizing Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Aseem Travedi was arrested and jailed for sedition in India. Kurt Westergaard of Denmark, who drew one of the first of the allegedly blasphemous Muhammad cartoons in 2005, was attacked in his heavily guarded home by an ax wielding assailant but escaped unharmed into a panic room built by the Danish governement.

In the digital age is political cartooning a lost art?

The newspaper political cartoonist in the United States has been in decline for the last two decades. But one of the primary reasons is the risk-averse nature of editors. They don’t want to offend readers, advertisers or politicians, especially with social media ready to bring a rabble to the virtual front door of the publisher.

As a result political cartoons have gone from being persuasive to simply reinforcing what one already knows and believes or, conversely, reinforcing what one despises and disagrees with. Seems they change few opinions. But great political cartoons are still being created in print and online, especially the latter. MH