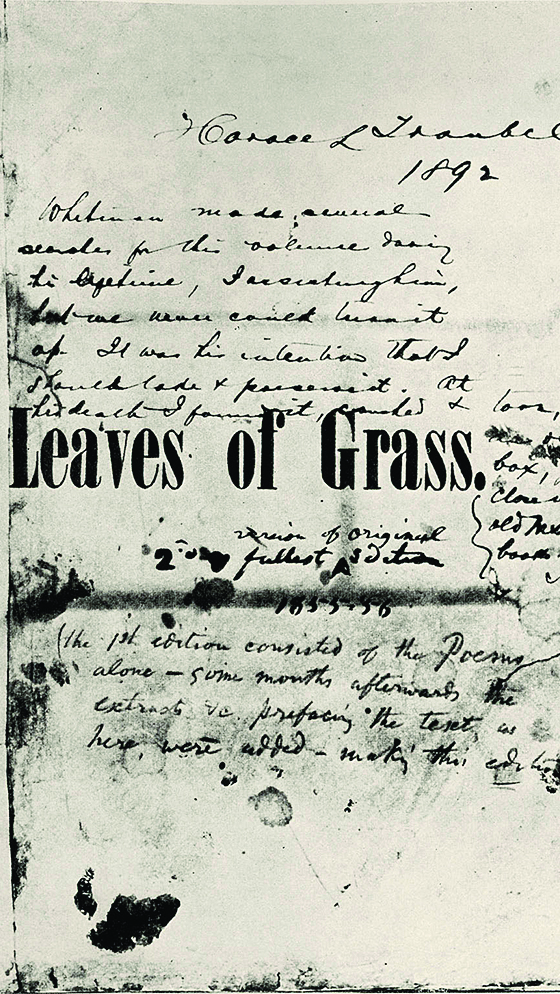

In the summer of 1855, an obscure 37-year-old Brooklyn newspaperman named Walt Whitman self-published a book of 12 lengthy, untitled, unrhymed poems. He called the volume Leaves of Grass. Few people noticed; fewer cared. But that September, The United States Review printed a long essay lauding Whitman. “An American bard at last!” the article began, unleashing a torrent of over-the-top praise. “Assuming to himself all the attributes of the country, steps Walt Whitman into literature,” the reviewer effused. “No sniveler or tea-drinking poet, no puny clawback or prude is Walt Whitman. He will bring poems fit to fill the days and nights—fit for men and women with the attributes of throbbing blood and flesh…”

The write-up was unsigned, but Whitman knew the author’s identity—he’d written it himself. He also penned two more anonymous reviews. They, too, were raves. In the Brooklyn Daily Times, Whitman touted Whitman as America’s bold new voice.

“A rude child of the people!” he crowed from the shadows. “No imitation—No foreigner—but a growth and idiom of America.” In the American Phrenological Journal, Whitman touted Leaves as “the most glorious of triumphs in the known history of literature.”

Whitman was indeed a great poet, among history’s most beloved and influential. A kindly man, he spent hundreds of hours visiting wounded soldiers recuperating in Washington, D.C., hospitals during the Civil War, bringing them candy and tobacco and writing letters for them.

Great poet and great soul, Whitman also possessed a less virtuous talent: He was a genius of hype, a master at public relations, and a peer of P.T. Barnum in advancing that great American art form—shameless self-promotion.

A hundred years before Muhammad Ali hollered “I am the greatest!” and 150 before Donald Trump declared, “I alone can fix it,” Walt Whitman was proclaiming, “I celebrate myself and sing myself.” His braggadocio wasn’t mere narcissism. He believed he was America’s poetic voice, so he schemed and scammed to make that voice heard. “Whitman was beyond scruples,” wrote biographer David S. Reynolds. “He felt his cause was worthy, and he would do anything in his limited power to push it.”

Born in 1819 on Long Island, Whitman left school at 11 to work as an office boy, printer, carpenter, and schoolteacher before becoming a writer for New York newspapers and editor of the Brooklyn Eagle. In 1842, he attended a lecture by America’s most respected author, Ralph Waldo Emerson, who challenged America to produce a poet worthy of its mountains, forests and factories. Whitman decided to become that poet.

Thirteen years later, he produced Leaves of Grass and immediately mailed Emerson a copy. Emerson responded by letter, calling the book “the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed,” and adding, “I greet you at the beginning of a great career.”

Ecstatic, Whitman showed Emerson’s letter to his newspaper pals. One, Charles Dana, ran the letter in the New York Tribune. Emerson was irate—it was a private missive, not meant for publication—and he felt exploited. But Emerson’s anger did not deter Whitman from reprinting the letter in a second edition of Leaves of Grass a year later, along with the cover blurb “I greet you at the beginning of a great career—R.W. Emerson.”

Ever ambitious, Whitman tried another trick. In the book, he quoted reviews, some laudatory—including those he wrote himself—and some scathing, including a Boston Intelligencer assessment mocking his work as “bombast, egotism, vulgarity and nonsense.”

“Whitman was testing out an advertising idea then quite new: controversy sells,” Reynolds wrote. A century later, Norman Mailer reprised Whitman’s tactic, buying a full-page ad for his novel The Deer Park, quoting the nastiest lines from the most scathing reviews.

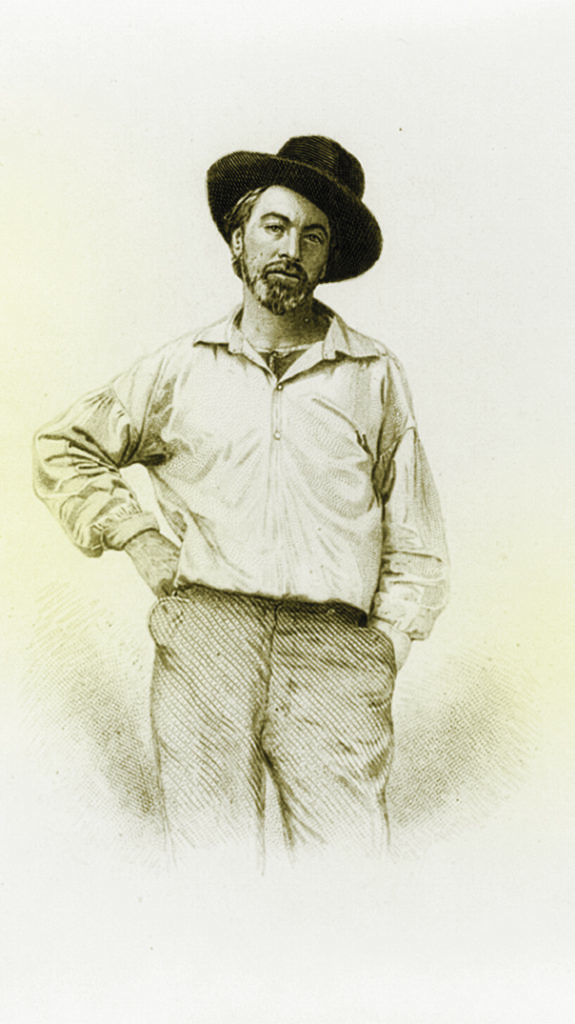

Whitman also pioneered the use of the new medium of photography to shape his public image. In the first edition of Leaves, a photo shows him in workman’s clothes, hat tilted jauntily. He has one hand in a pocket and the other cocked defiantly on his hip. In an era when authors were invariably portrayed seated in libraries wearing their best suits, Whitman’s picture was shocking. But it worked. Reviewers noted that the poet looked like a “loafer” with an “air of mild defiance and an expression of pensive insolence.” Which was exactly the image Whitman wanted to convey: He was the poetic voice of the common man.

As he grew older and came to crave respectability, Whitman let his white hair and white beard grow shaggy, a look documented in photos meant to burnish his image as a saintly “good gray poet.”

One photo portrayed him like Saint Francis of Assisi, with a butterfly perched on his fingertip. He swore the insect was real, bragging that he possessed “the knack of attracting birds and butterflies and other wild critters.” But the thing with wings was a cardboard prop—it now resides in the Library of Congress.

Like most self-promoters, Whitman wildly exaggerated his popularity. To hype that second edition of Leaves, he wrote that he’d printed 1,000 copies of the first edition, and “they readily sold.” Then he added this whopper: “…the average annual call for my Poems is ten or twenty thousand.” In truth, as he complained to friends, he doubted “if even ten were sold.” As Whitman famously wrote, “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself. (I am large, I contain multitudes.)”

In time, Whitman shifted from writing anonymous reviews praising his own book to churning out pseudonymous feature articles praising himself. In 1872, he composed “Walt Whitman in Europe,” an essay extolling his alleged popularity on the Continent—“radiating there in all directions in the most amazing manner.” He mailed the manuscript to his friend Richard Hinton, a Kansan, with instructions: “Sign this with your name at the conclusion and send it at once to the Kansas Magazine.” Hinton obeyed. The article ran. Then Whitman convinced two Eastern newspapers to reprint it.

“Walt, some people think you blew your own horn a lot,” his friend Horace Traubel noted while interviewing Whitman.

The poet grumbled, then said, “I have merely looked myself over and repeated candidly what I saw.”—a great line from the font of so many great lines. Later, he defended his shameless self-celebration in a sentence that could serve as a motto for America’s armies of publicists and PR people. “The public is a thick-skinned beast,” Walt Whitman said, “and you have to keep whacking away on its hide to let it know you’re there.”