By the latter half of the 19th century international trade had become increasingly important to the power and influence a nation was able to project. Great Britain, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain were among the significant Western rivals, as was a spirited new contender, the United States, which was increasingly flexing its foreign-relations muscles. In the summer of 1871 the hermit kingdom of Korea became an unintentional pawn in the latter’s rise as a global economic and military power.

Notwithstanding the growing import of international trade as a measure of world status, the millennia-old Korean realm stubbornly resisted being swept up into “corrupting” trade agreements with Western countries. As the ruling Joseon dynasty crafted its foreign policy, it drew lessons from China’s humiliating mid–19th century Opium wars with Britain. Its isolation was self-imposed. But could it resist the global tides of change? The rapidly developing industrialization of war in Western nations—especially the development of increasingly lethal battlefield weaponry—proved a wild card in the events that characterized that contentious era.

Such dynamic geopolitical circumstances formed the backdrop for the 1871 U.S. Expedition to Korea, which culminated in the Battle of Ganghwa. Though its operational name might evoke an old-time Boy Scout jamboree, the “expedition” was in fact a U.S. Navy/Marine Corps joint combat operation. The Koreans recalled it as Shinmiyangyo, or “Western Disturbance in the Shinmi Year [1871].”

While largely dismissed by modern historians (a recent U.S. Naval Institute News article referred to Ganghwa as “an obscure 19th century military action”), the 1871 battle foreshadowed current concepts of global force projection, particularly by means of amphibious warfare. It also was an inexact, if thought-provoking, precursor of both the Korean War of 1950–53 and the lingering diplomatic tensions between a still-enigmatic North Korea and a globally oriented United States.

The catalyst of the 1871 expedition was an attack on the side-wheel steamer General Sherman, an armed, American-flagged merchant ship of dubious reputation. In July 1866 the trading vessel entered Korean waters uninvited and fell afoul of local officials. In the violent exchange that followed, Korean soldiers besieged the steamer in a channel opposite Pyongyang, ultimately destroying it with a fireship and killing every member of its crew. Inquiries from U.S. diplomats concerning the fate of General Sherman and its mostly American crew went unanswered for five years.

Finally, in 1871 Washington decided to bolster its inquiries with action, sending to Korea the newly formed U.S. Navy Asiatic Squadron, led by Rear Adm. John Rodgers. As a young officer in the mid-1850s Rodgers had earned modest diplomatic credentials with his participation in the opening of U.S.–Japanese trade relations, spearheaded by Commodore Matthew Perry, who had served under Rodgers’ namesake father during the War of 1812. Embarking with the squadron was U.S. Ambassador to China Frederick Low, with a twofold mission: to investigate the circumstances of General Sherman’s destruction and to secure a trade agreement with Korea.

While Low’s secondary objective was inarguably more far-reaching, a contemporary account in The New York Times played on the more jingoistic aspects of the Asiatic Squadron’s mission, exclaiming the undertaking would produce a “Detailed Account of the Treacherous Attack of the Coreans [sic]” with “Speedy and Effective Punishment of the Barbarians.”

The weight accorded Low’s mission could be measured by the Asiatic Squadron’s conspicuous firepower. Its vessels included the flagship screw frigate USS Colorado (with two 150-pounder rifled guns, one 11-inch gun, forty-two 9-inch guns, two 20-pounder howitzers and six 12-pounder howitzers), the screw sloops-of-war USS Alaska and USS Benicia (each with one 60-pounder howitzer, one 11-inch gun and two 20-pounder rifled guns, Benicia with an additional ten 9-inch guns), the side-wheel gunboat USS Monocacy (with two 60-pounder howitzers and four 8-inch guns) and the gunboat USS Palos (with four 24-pounder howitzers and two 24-pounder rifled howitzers). Also aboard the ships were 542 armed sailors and a detachment of 109 Marines commanded by Capt. McLane Tilton, fleet Marine officer of the Asiatic Squadron from 1870 to 1873.

The squadron’s uncounted but tactically important small launches, cutters and whaleboats would ferry men and materiel between the ships and shore. Such craft were the improvised precursors of the specialized, bow-ramped “Higgins boat” landing craft many historians largely credit for the Allied victory in World War II.

On May 24 the fleet reached Asan Bay, dominated by Ganghwa Island, at the mouth of a river network leading to the capital city of Hanyang (present-day Seoul, South Korea). Guarding the approach were three forts, beyond which rose a citadel, strategically sited at a narrows farther upriver. The terrain was irregular, with numerous ravines and rough ground. In a letter to his wife Tilton wrote of the countryside’s “beautiful hills and inundated rice fields.”

On June 1, with the fleet at anchor and negotiations under way at Inchon, Palos and Monocacy set out to survey the bay and shoreline; Korean shore batteries promptly fired on them. After shelling the forts into silence, the gunboats returned to the fleet. There were no U.S. casualties, but Adm. Rodgers filed a protest with the Joseon government, demanding a formal apology within 10 days, or he would pursue retaliatory action.

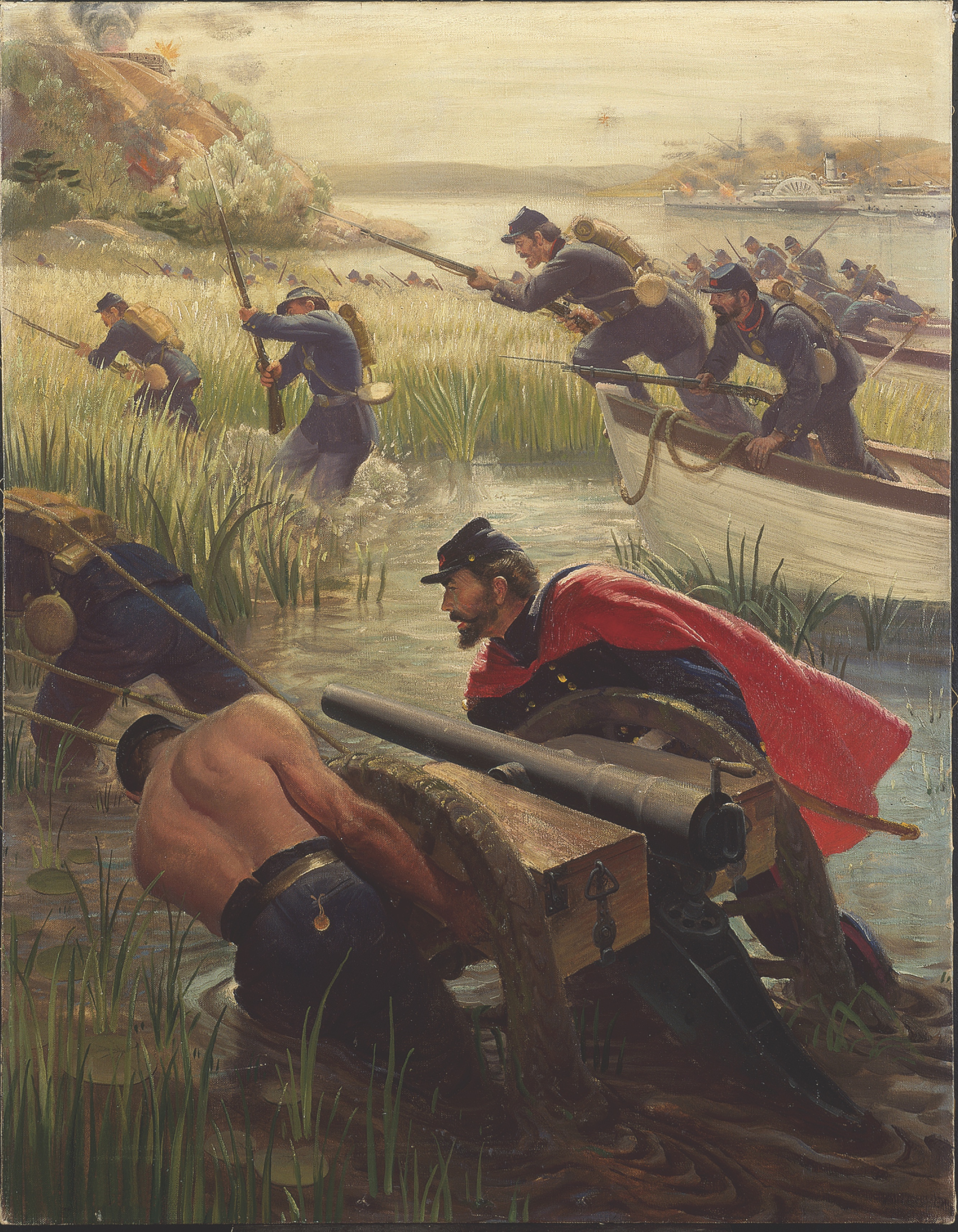

On June 10, with no Korean response, Rodgers—albeit a day prematurely—launched a full-blown amphibious assault, deploying the Marine detachment and armed sailors. In his after-action report the admiral described the initial landing:

The point chosen for the disembarkation, while seemingly as good as any in other respects, was for military reasons deemed the best, since it flanked the enemy’s works and left nothing to be feared in our rear.

The character of the shore was unknown, and it proved to be most unfavorable for our purpose. Between the water and the firm land a broad belt of soft mud, traversed by deep gullies, had to be passed. The men, stepping from the boats, sank to the knees, and so tenacious was the clay that in many cases they lost gaiters and shoes and even trowsers’ [sic] legs.…

As soon as firm ground was attained, the infantry battalion was formed, and the Marines deployed as skirmishers. The advance at once began, and the first fort [Ch’o ji jin, renamed the Marine Redoubt] was quietly occupied.

After destroying its walls and stores and either spiking or casting its guns into the estuary, the attackers encamped outside the ruined fort—becoming the first Western troops to camp on Korean soil. The next morning the Americans methodically attacked, overran and razed the remaining forts. About 300 defenders remained holed up in the heavily defended, horseshoe-shaped citadel—the Koreans’ last bastion. Massing behind a hill within 150 yards of its walls, the Americans readied their assault.

The attack order came around noon. Leading the charge was young Navy Lt. Hugh McKee, one of Rodgers’ flagship officers, who was killed as he bounded over the parapet. The fight, though it lasted less than a half-hour, was especially bitter. Rodgers recalled the opening action:

When all was ready, the order to charge was given by Lt. Cmdr. [Silas] Casey, and our men rushed forward down the slope and up the opposite hill. The enemy maintained their fire with the utmost rapidity until our men got quite up the hill, then, having no time to load, [the Koreans] mounted the parapet and cast stones upon our men below, fighting with the greatest fury.

The Koreans’ desperate use of stones as weapons underscores the disparity in arms between the American attackers and Korean defenders. The latter also employed antiquated cannons—some lashed to logs—as well as spears, swords and tripod-mounted matchlock muskets dating from the 15th century.

In contrast, the sailors in the shore party were armed with modern, rapid-firing .50-caliber Remington rolling-block carbines. The Marines’ Springfield muskets, while older than their Navy comrades’ firearms, were still far superior to Korean weaponry. In support of the assaulting troops the five U.S. warships rained devastating gunfire on the citadel’s defenders. The results were unsurprising—three Americans were killed to 243 Koreans. As the garrison fell, the fighting abruptly ceased.

In the wake of the battle U.S. officers recommended Medals of Honor for nine sailors (Ordinary Seaman John Andrews, Quartermaster Frederick Franklin, Chief Quartermaster Patrick Grace, Carpenter Cyrus Hayden, Landsman William Lukes, Boatswain’s Mate Alexander McKenzie, Landsman James Merton, Quartermaster Samuel Rogers and Ordinary Seaman William Troy) and six Marines (Cpl. Charles Brown and Pvts. John Coleman, James Dougherty, Michael McNamara, Michael Owens and Hugh Purvis). Excerpts from their award citations reflect the ferocity of the battle:

Fighting courageously in hand-to-hand combat, Owens was badly wounded by the enemy during this action.

Fighting courageously at the side of Lt. McKee during this action, Rogers was wounded by the enemy.

Advancing to the parapet, McNamara [wrenched] the matchlock from the hands of an enemy and [killed] him.

Braving the enemy fire, Purvis was the first to scale the walls of the fort and capture the flag of the Korean forces.

Serving as color bearer of the battalion, Hayden planted his flag on the ramparts of the citadel and protected it under a heavy fire from the enemy.

The citations speak to a valor beyond raw courage under fire. Marine Pvt. Coleman’s citation praises him for saving the life of fellow medal recipient Boatswain’s Mate McKenzie, highlighting the selfless camaraderie that bonded the Marines and sailors. Marine Cpl. Brown is commended for his efforts in “capturing the Korean standard in the center of the citadel of the Korean fort,” a symbolic achievement more commonly associated with earlier battles and times. (The roughly 15-square-foot Sujagi battle standard was later sent to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md., adhering to an 1849 order by President James Polk that any such flags, standards or colors captured by the Navy be housed there.) Still other citations detail the truly savage nature of hand-to-hand fighting at the height of the siege. All underscore the truism that while higher-ups may do the grand strategizing, it is the nameless, often thankless warrior who “makes it so.”

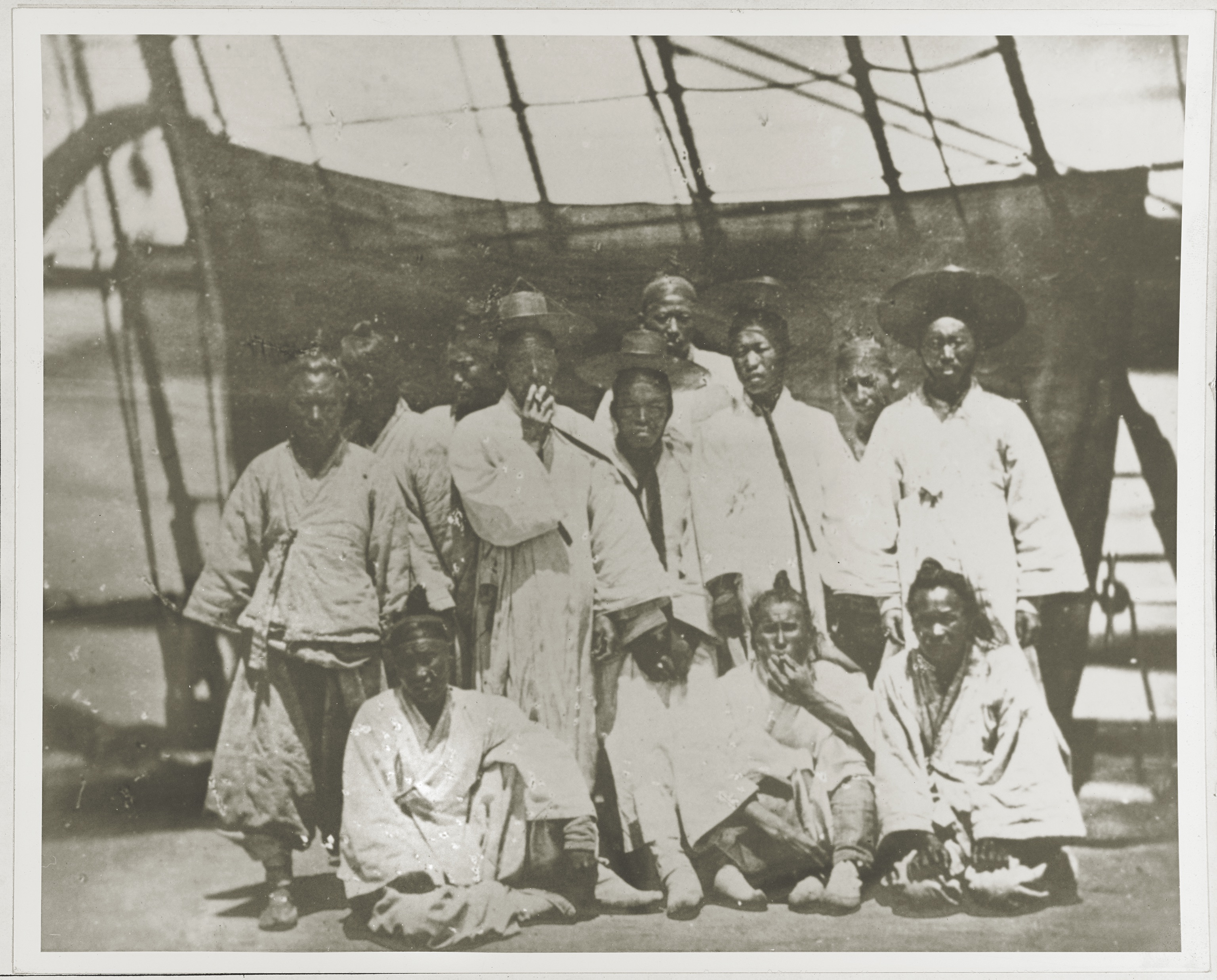

The technologically overmatched defenders had fought hard, most to their deaths, including General Eo Jae-yeon. To the Koreans surrender was unthinkable, and Tilton underscored their total commitment in a letter to his wife. They were fighting not solely for their own survival, he explained, but for the survival of their families and the community at large. “The Corean [sic] soldiers fought like tigers, having been told by the king [Gojong], if they lost the place, the heads of everybody on Kang Hoa [sic] Island, on which the forts stood, should be cut off.”

On July 3 the Asiatic Squadron withdrew and sailed for the consular port at Chefoo, China. If nothing else, the Battle of Ganghwa had demonstrated growing U.S. military confidence and prowess, notably in the discipline of amphibious warfare. The engagement represented a violent collision between centuries-old, inward-focused traditions and the New World of international trade, industrial technology and global power projection. It also sent a forceful message—that depredations against U.S. citizens would henceforth incur severe military consequences. Despite their tactical victory at Ganghwa, however, the Americans were unable to wrest a corresponding trade agreement from the chastened kingdom. In fact, the battle fostered profound resentment among the Koreans, who attached deep emotional significance to the ancient glories of their hermit kingdom.

That said, the threat of American military projection did prove a critical boon for U.S. economic interests in the region and usher in a more stable environment for world trade. In his concise survey The U.S. Navy: A History author Nathan Miller deftly sums up the battle and its long-range implications. “Although Rodgers’ attempt to blow open the door to Korea failed,” he writes, “it did prepare the way for Commodore Robert W. Shufeldt to negotiate a treaty between Korea and the United States in 1881—the first that Korea signed with a Western nation.”

By the turn of the 20th century, no matter how the Koreans felt about modernization at the hands of Western European nations, their country—and indeed the entire region—was on a steady, irrevocable path to change. The question remains whether they can meet future challenges with any measure of the unity they once shared as a kingdom.

Retired U.S. Navy Rear Adm. Joseph F. Callo is a New York–based historian and writer on maritime topics. For further reading he recommends The U.S. Navy: A Concise History, by Nathan Miller, and The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power, by Max Boot.