George Washington received word of the disaster one evening in early November 1791 while entertaining guests at the Executive Mansion on Market Street in Philadelphia. His secretary, Tobias Lear, discreetly whispered in the president’s ear as he sat at the head of the dinner table. Although accustomed to receiving bad news during his long and tumultuous career, Washington was stunned by what he heard. The U.S. Army, under the command of Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair, had been annihilated by a confederation of Indian tribes along the Wabash River in the Northwest Territory.

Among the president’s many attributes was tremendous self-control.

Returning to dinner that evening, he apologized for his absence and resumed his role as gracious host. Only after his guests had departed did Washington’s rage surface. “It’s all over!” he cried out to his startled secretary.

“St. Clair is defeated—routed!” Pacing the room in agitation, he again exploded. “Here on this very spot I took leave of him. ‘You have your instructions,’ I said, ‘from the secretary of war. I had a strict eye to [the Indians] and will add but one word—beware of a surprise. I repeat it, beware of a surprise—you know how Indians fight us.’ He went off with that as my last solemn warning thrown into his ears.”

The warning had gone unheeded and the Army had been destroyed. “Oh, God! Oh, God!” exclaimed

Washington in despair and anger at St. Clair’s folly. “He’s worse than a murderer!”

Britain ceded the Northwest Territory to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris at the close of the American Revolution. Engulfed in a global war with France, eager to end the drawn-out and costly conflict with its rebellious colonies, and cognizant of the near impossibility of defending the territory from French, Spanish, and American encroachment, Britain granted the new nation a quarter-million square miles of wilderness.

The British treaty negotiators were hazy regarding the size of the vast territory in question—it would eventually be carved into the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin. Nor were the negotiators concerned that the trackless territory was inhabited. Tribal nations that had supported the British during the war—and had counted on British support to formalize their ownership of the land—were left in the lurch.

The Confederation Congress (the federal government was still stumbling along under the Articles of Confederation, ratified in 1781) saw in the vast lands an opportunity to pay off the nation’s enormous war debt, as it lacked the authority to levy taxes. Encouraged by self-interested land speculators, in 1787 Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, intended to drive expansion into the new territory through public land sales.

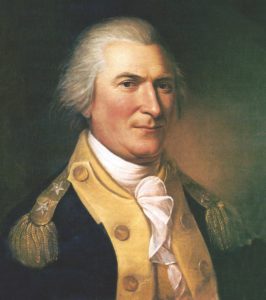

St. Clair / Alamy

There was an attempt to acknowledge the rights of the region’s Indians through treaty negotiations. But there were two major problems with this approach. One, the settlers flowing west neither knew nor cared about treaty-driven boundaries and squatted on the land they found most promising. And two, the Indians lacked deeds or property covenants, thus the question of land ownership was often in flux. Various tribal leaders happily sold land they didn’t actually occupy, and harried U.S. negotiators would make treaties with a dozen tribal chiefs, only to discover there were a dozen others who refused to recognize the agreement. As one Shawnee chief succinctly stated the issue, “God gave us this country—we do not understand measuring out the land; it is all ours.”

Given the state of affairs, it is not surprising that Indians and settlers across the Northwest Territory were embroiled in a bloody but undeclared war, leading one early settler and land speculator to plaintively ask, “Of what value are lands without inhabitants, and who will wish to inhabit a country where no reasonable protection is afforded?”

Frustrated by the failure to negotiate a peaceful takeover of the Northwest Territory, and subject to the increasingly desperate pleas of settlers in the contested lands, the Washington administration determined to settle the question through the application of military force.

In September 1790 Washington and Secretary of War Henry Knox ordered Brevet Brig. Gen. Josiah Harmar, the commander of U.S. forces along the Ohio River, to march north from Fort Washington (present-day Cincinnati) and destroy the villages of particularly recalcitrant tribes at the head of the Maumee River (near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana). Instructed to eliminate any hostile forces along the way, he was to settle the land ownership question once and for all. The Indians knew he was coming. In a monthlong campaign Harmar and his army of 1,133 untrained militiamen and 320 Regulars of the 1st American Regiment (the bulk of the U.S. Army at the time) burned a few deserted villages, destroyed crops and were then trounced in a series of engagements by the aforementioned recalcitrant hostiles. Declaring victory and leaving the field, Harmar abandoned dozens of casualties and piles of equipment during his rapid return to Fort Washington.

Knox summarized the failed punitive expedition in a letter to the chastised Harmar, telling him his efforts would “not induce the Indians to peace, but on the contrary encourage them to a continuance of hostilities.” A subsequent court-martial, at the general’s request, cleared Harmar of wrongdoing, but Knox’s blunt assessment was all too accurate—the bungled campaign only furthered the need for a decisive military incursion into the Northwest Territory tribal stronghold.

The federal government acted quickly to address deteriorating conditions along the Ohio. In March 1791 Congress authorized the establishment of a second infantry regiment (doubling the size of the standing Army) and initiated the recruitment of levies (men conscripted into federal service) for six months of service in the Northwest Territory. Neither Regulars nor militia, the levies exhibited the weaknesses of both. Though led by Regular Army officers, they were poorly trained, poorly paid and poorly motivated. Working on the premise that quantity was cheaper than quality, the government believed that marching enough short-term enlistees into the forest would somehow prompt the submission of the warring tribes.

To lead this military hodgepodge, Washington (usually a good judge of military leadership) selected Arthur St. Clair, then governor of the Northwest Territory. A British officer during the French and Indian War, St. Clair had served with the Continental Army throughout the Revolutionary War, rising to the rank of major general. Known primarily for having abandoned the key American fortress of Fort Ticonderoga in upper New York without a fight in 1777, the general did have some knowledge of the territory in which he was about to lead an army. Unfortunately, he had little knowledge of (or regard for) the foe he was about to face. He was also 54 years old, overweight and suffered severely from gout.

The War Department provided criminally poor support to St. Clair in the lead-up to the campaign. Knox appointed two cronies (one corrupt, the other incompetent) to serve as chief contractor and quartermaster. The expedition was delayed for months due to a breakdown in the supply chain and an inability to expeditiously recruit troops and transport them to the assembly point at Fort Washington.

Per Washington’s instructions, St. Clair appointed Maj. Gen. Richard Butler as his second-in-command, in charge of the levies. Also a veteran of the Revolutionary War, Butler had experience both fighting and negotiating with the tribes as an Indian commissioner in the territory. He quickly developed a contentious relationship with his new commander—which would play a major role in the impending tragedy.

The leadership and logistics problems paled to insignificance when compared to the warfighting doctrinal problem—the Army was not trained to fight in the wilderness against Indians. Though the minutemen of Lexington and Concord fame fought effectively from cover behind trees and walls, most engagements fought by the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War followed the European model—ranks of infantrymen closing on one another in the open and firing on command. The latter was the warfighting method with which St. Clair was familiar. And though there were scores of frontiersmen in Ohio country who could hold their own in any wilderness battle, such individuals were not part of the Army being recruited—one not being trained to fight an elusive foe in the deep forest.

As St. Clair struggled to address the supply and manpower issues, legislators in Philadelphia (then seat of the federal government) brought increasing pressure to initiate the campaign. His orders were to build a military road between the Ohio and Wabash, establish garrisons along the route, erect a permanent post at the site of Harmar’s defeat and eliminate any tribal warriors who attempted to stop him. The ever-helpful Knox let St. Clair know the president wanted the operation started immediately and lamented the continuing delays.

Finally succumbing to the pressure, St. Clair and his 2,300-strong band of Regulars and levies set out from Ohio country in early October, determined before winter to march some 170 miles through the trackless forest to the Maumee, building the road while advancing.

Poorly provisioned and equipped, the Army crawled north at a snail’s pace of perhaps 4 miles per day. The men lacked sufficient numbers of axes to adeptly blaze a trail, and freezing rain made a mockery of the poor-quality clothing and camp equipment with which the Army had been supplied. The senior commanders also started squabbling among themselves, reaching a breaking point when St. Clair publicly upbraided his deputy, Butler, for having ignored his orders to cut two parallel roads, each 40 feet wide, through the dense forest; in the interest of speed Butler had unilaterally elected to go with one 12-foot trail. Though St. Clair assumed active command, the pace did not increase. Two weeks into the march the general put his men on half rations due to food shortages, and the hungry, freezing, unsheltered levies began to desert in droves. Those who didn’t desert made it clear they intended to bolt the minute their enlistments were up. The Army was melting away.

St. Clair halted the crumbling force in mid-October and set the men to work building a fort. There amid soaking rains the general waited for desperately needed supplies to arrive. On October 23, after having two deserters hanged, he resolved to address the short-term enlistment issue by marching his troops ever deeper into the woodlands, leaving them little recourse but to remain with the Army. The next morning the column resumed the march. Despite these crowd-pleasing measures, morale did not improve. While failing to win friends or influence people among his disgruntled command, St. Clair’s health deteriorated such that he was no longer able to ride a horse. One of his subordinate commanders recalled the sight of the general being carried on a litter “like a corpse between two horses”—hardly a spectacle to inspire confidence.

As the Army slogged forward, Indian scouts sent out by Miami Chief Little Turtle and Shawnee Chief Blue Jacket, at the head of more than 1,000 warriors from several tribes, kept their commanders informed regarding the trials, tribulations and progress of the lumbering column. Among those stalking the soldiers was a young Shawnee warrior named Tecumseh, who would become a famous chief in his own right in coming decades.

The Army had Indian scouts of its own—20 Chickasaw warriors eager to settle ancient scores against the northern tribes. Unfortunately for St. Clair, they proved the least effective scouts ever to slip on a pair of moccasins. Though the Chickasaws rooted out a few enemy scouts, they failed to detect the warrior army skulking in the woods around the American column. Not that St. Clair was overly concerned regarding the dearth of intelligence regarding his foe. While acknowledging that tribal warriors were superb individual fighters, he believed they lacked the discipline and centralized leadership to confront his troops en masse.

Amid crashing thunder on the night of October 30–31 about 60 of the increasingly skittish levies abruptly decided their service was at an end and deserted. While their departure probably increased the combat effectiveness of St. Clair’s force, his reaction to it sealed the fate of the expedition. Concerned the missing levies might plunder the supply trains crawling along behind the column, the general dispatched his only effective force, the Regulars of the 1st U.S. Infantry Regiment, to protect the packhorses and round up the deserters. With his hasty action St. Clair ensured that 300 of his best soldiers would not be available for the forthcoming battle.

On November 3 the Army encamped on open high ground along a shallow tributary of the Wabash within 50 miles of the target villages. St. Clair deployed 1,100 men, the main body of levies and Regulars, in two lines about 70 yards apart, forming a hollow square. Eight artillery pieces the men had dragged through the forest were deployed in two batteries of four guns each—one battery facing east, the other west. The nearly 300 remaining levies were sent across the shallow creek to serve as an advance guard—and to make it more difficult for them to slip away and join their recently absconded compatriots. It was snowing, the men were cold and hungry, and no effort was made to dig in or fortify the positions on the bluff. St. Clair did order all units to send out scouts for security—an order ignored by most of his field commanders.

One subordinate did send out scouts. Butler, the disgruntled second-in-command, dispatched a scouting party under Captain Jacob Slough, who reported the woods were crawling with warriors. Butler dismissed the report, telling Slough the general had treated all his proposals with contempt and would probably not appreciate the latest intelligence. He neither shared the report with St. Clair nor took defensive measures.

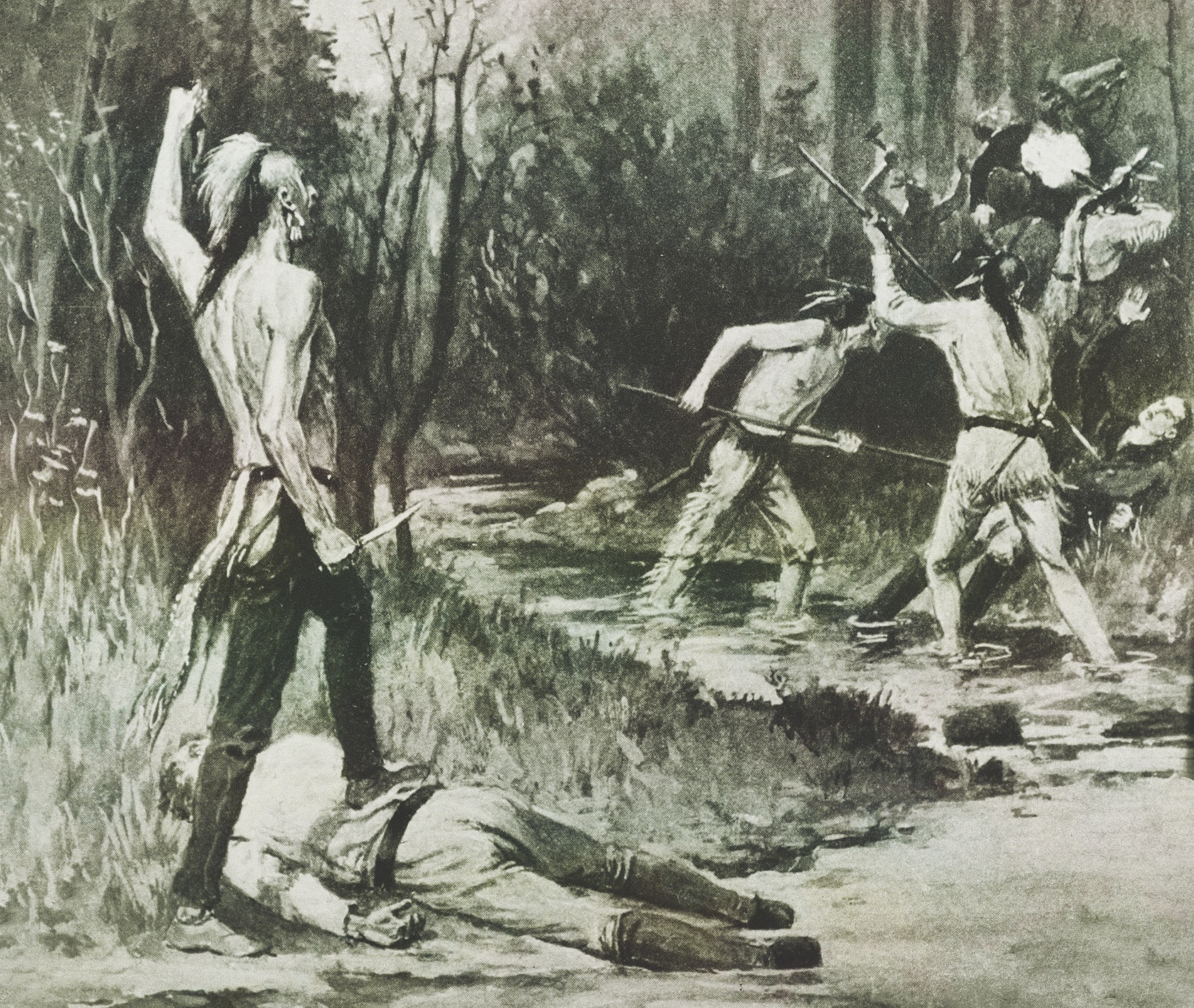

Thirty minutes before sunrise on November 4 the officers took roll call. The camp was awake, though hardly alert, when sporadic firing broke out in the direction of the advance guard across the creek. Confirmation the column was under attack came minutes later as scores of panic-stricken levies came splashing across the creek and crashing through the mass of soldiers assembled on the high ground. Close on their heels were several hundred screaming tribal warriors. Despite the frightful noise and confusion, units on the bluff managed to repel the initial attack with discipline and fixed bayonets. However, in a carefully orchestrated maneuver by Little Turtle and Blue Jacket follow-on waves of warriors surged around both flanks of the American position and soon had the force surrounded.

The gout-ridden but game St. Clair alternately hobbled about or was borne by litter along the firing line, where he sought to bring some order to the chaos. Unfortunately, he had little choice but to fight from the hollow square formed by the encampment. His men made perfect targets, standing in loose formation and fruitlessly attempting to fight an unseen foe who, from cover and concealment, poured fire into the American ranks. Situated too high, the artillery proved of little value, the gunners unable to depress the muzzles of the weapons and therefore only able to fire harmlessly over the heads of the attackers. The barrage generated a lot of smoke, making it that much more difficult for the infantrymen to identify targets. Ninety minutes after the attack began, the artillery fell silent. With the gunners all dead or wounded, survivors had little choice but to spike the cannons.

Unable to effectively fire on the elusive enemy, several units instead charged into the woods with fixed bayonets. The tribal warriors simply withdrew in front of the brave but futile charges, then worked their way around the flanks of the onrushing soldiers to continue the slaughter. In at least two instances they moved into gaps left by the attacking Americans and briefly broke through into the interior of the hollow square.

Instructed by their chiefs to aim for the men wearing the gaudiest uniforms, the warriors followed those instructions to the letter, quickly eliminating many of the field officers. Butler himself was shot from his horse and tomahawked. Able-bodied soldiers dragged the wounded within the hollow square, where they competed for space with noncombatants, including some 400 camp followers, the panicked levies and other shocked, dispirited, leaderless soldiers.

Shortly after 9 a.m., after three hours of bloody, close-quarters combat, St. Clair ordered a retreat. The surviving Regulars punched a hole through the warrior lines with a bayonet attack, and the rout was on. Cannons, camp equipment, small arms, ammunition, the dead, the wounded—all were abandoned as the remnant of the U.S. Army fled down the road they had so recently constructed. The last to leave reportedly propped the badly wounded Butler against a tree, handed him a loaded pistol and left him to his fate (which was not to die comfortably in bed of old age).

Others manhandled St. Clair atop a packhorse and joined the column of refugees streaming down the trail. There was little pursuit by the victors, who were more interested in plundering the camp and massacring the wounded. The bulk of the defeated horde staggered into Fort Washington four days later. Of the 1,400 or so soldiers and 400 camp followers at the Wabash, more than 1,000 had been killed or wounded. There were just 61 tribal casualties.

Washington’s outrage and despair were short-lived, soon supplanted by the determination and resolution that characterized his entire public life. Exploiting the Wabash disaster as an object lesson, he convinced Congress to authorize formation of a larger, better supported Army, and he chose a different sort of commander to lead it—Maj. Gen. “Mad Anthony” Wayne, a Revolutionary War veteran whose fellow soldiers had bestowed on him a nickname reflective of his aggressiveness and tenacity.

Wayne organized the new force, dubbed the Legion of the United States, trained its soldiers in wilderness fighting and on Aug. 20, 1794, routed Blue Jacket’s tribal confederation along the Maumee at the Battle of Fallen Timbers (just southwest of present-day Toledo, Ohio). A year later the defeated tribal chiefs ceded much of the disputed territory to the United States, ending nearly a decade of bitter fighting, shattering their dreams of an independent tribal homeland and opening the gates to a flood of new settlers along the Ohio. MH

James F. Byrne Jr. is a retired U.S. Army officer and frequent contributor to Military History. For further reading he recommends The Victory With No Name, by Colin G. Calloway, and The Life of George Washington, by Washington Irving.

This article appeared in the July 2020 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: