WHEN I WENT TO GERMANY in the early 1970s, the roads swarmed with Volkswagen Beetles—squat, misshapen little beasts bustling about city streets or rattling along the autobahns with their noisy, air-cooled engines, curved roofs tapering to a point at the back, and, in older models, oval back windows so tiny I wondered how a driver could see anything in his rearview mirror. Their exterior ugliness, however, was nothing in comparison to the horror of riding inside one: sitting in the back seat, as I often had to when being driven around, I was oppressed by the claustrophobia imposed by the low roof, while the loud rattling and whirring of the engine behind me quickly gave me a headache, made worse in winter by the heating system’s repulsive smell. Turning corners at speed—such speed as the vehicle could muster—was a nightmare, as the car rocked and rolled and churned my stomach.

Yet the Beetle was the most successful car of its time. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, when one car in three on West German roads was a Beetle, sales exceeded one million each year. In 1972, total sales of the Beetle—a truly global vehicle—passed those of the century’s most popular passenger car, Henry Ford’s Model T. It was an amazing accomplishment for a vehicle whose origins were hardly auspicious.

Though after World War II most people chose to ignore the fact, the Beetle began life in the 1930s as a pet project of Adolf Hitler. Once in power, Hitler was determined to bring Germany up to what he thought of as the modernity common in the United States and other advanced economies. Few people in Germany owned radios, so Hitler’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, introduced the Volksempfänger (People’s Receiver), a cheap and cheerful little wireless—short-wave so listeners couldn’t tune into foreign broadcasts. Fridges were even rarer, so the Nazi government introduced the Volkskühlschrank (People’s Refrigerator). Soon many other products had similar names and similar intentions. (See “Products for the People,” May/June 2015.)

THE PEOPLE’S CAR—the Volkswagen—belonged to this milieu. Although it was widely referred to by that name, its official title was the “Strength through Joy Car” (the Kraft durch Freude-Wagen, or KdF-Wagen), signifying its association with the German Labor Front leisure program that went by the same name and whose purpose was to reward German workers with affordable diversions.

From the outset, Hitler was determined to modernize Germany’s roads. In the early 1930s, Germany was one of Western Europe’s least motorized societies. Even the British had six times more cars relative to population. This was partly because German public transport was second to none—smoothly efficient, quick, omnipresent, all-encompassing. Germans mostly felt no need for cars. And had they wanted cars, they couldn’t have afforded them. The economic disasters of the Weimar Republic had depressed demand. So empty were German roads that Berlin, a lively metropolis, did not find it necessary to install traffic lights until 1925.

Three-quarters of German workers were laborers, artisans, farmers, and peasants, unable to purchase expensive products by Daimler-Benz or the country’s 27 other car makers, whose inefficient production methods and small outputs led to models that only members of the country’s intermittently affluent bourgeoisie could buy.

To reach American levels of car ownership, Hitler told the automobile show in Berlin in 1934, Germany had to increase the number of cars on its roads from half a million to 12 million. To the further dismay of German nationalists, the two most successful mass vehicle manufacturers in the country were based in the United States: Ford, which opened a factory in Cologne in 1931, and General Motors, which operated the Opel car factory at Rüsselsheim. By the early 1930s, Opel cars were dominating the passenger vehicle market in Germany, with 40 percent of annual sales

Hitler pursued motorization on several levels. Building the famous Autobahnen was one. Another was the promotion of motor racing. Hefty government subsidies brought German speedsters by Daimler-Benz and Auto Union victory in 19 of 23 Grand Prix races held from 1934 to 1937.

Ideology played an important role. In the interests of national unity, the government replaced local regulations with a Reich-wide Highway Code. Far from straitjacketing drivers, the 1934 Code placed its trust in the Aryan’s consciously willed subordination to the racial community’s interests. On the road, owners of expensive cars had to put “discipline” and “chivalry” first and set aside outmoded class antagonisms. Jews, of course, couldn’t be trusted to do this, so from 1938 on they were banned from owning or driving cars.

The automobile, Hitler declared, responded to the individual will, unlike the railway, which had brought “individual liberty in transport to an end.” So the Highway Code abolished speed limits—with catastrophic results. In the first six years of the Third Reich, accident rates on German roads climbed to become Europe’s highest. By May 1939 the regime had to admit defeat and set speed limits on all roads except the autobahns, still Europe’s most terrifying roads.

Cars, Hitler proclaimed, had to lose their “class-based, and, as a sad consequence, class-dividing character.” They had to be available to everyone. What was needed was a home-built vehicle that bridged the social divide. Hitler commissioned Austrian engineer Ferdinand Porsche to design an affordable car for ordinary people. (In a typically Nazi addendum, officials stipulated that the hood be stout enough to accommodate a machine gun if necessary.)

Ambitious and politically skilled, Porsche secured Hitler’s backing for a huge factory that emphasized streamlined production techniques. The Labor Front put its vast financial reserves at Porsche’s disposal and sent the designer on a tour of automotive factories in the United States, where he hired engineers of German extraction to take back with him to work on the new car. Hitler opened the Volkswagen factory near the village of Fallersleben, in what is now Lower Saxony, in 1938. In time an entire new town, Strength through Joy City, was to be built to house and serve auto workers.

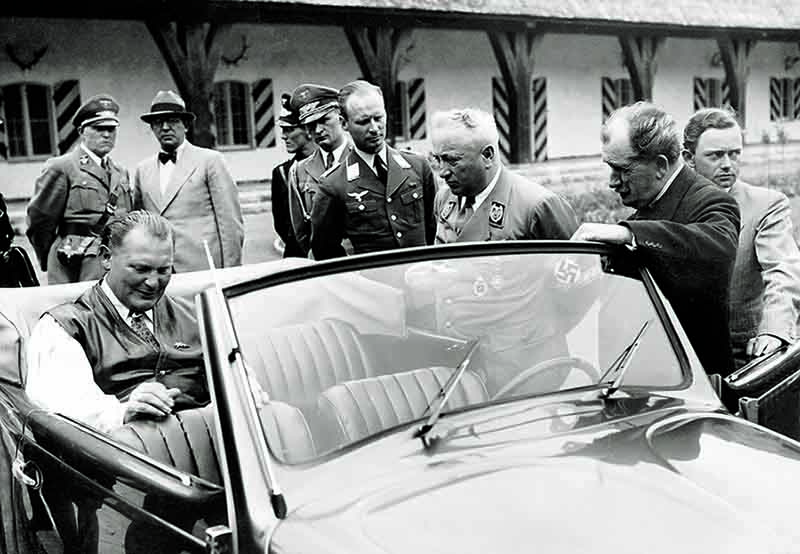

In his comprehensive history of the Beetle, The People’s Car, Bernhard Rieger describes the elaborate groundbreaking ceremony held at the site. “Fifty thousand spectators, most of whom had been transported to the deep countryside by special trains, set the stage for the hour-long ceremony broadcast live on national radio,” Rieger writes. “In the cordoned-off area reserved for Hitler and his entourage, three models of the ‘people’s car’—a standard limousine, a limousine with a retractable canvas roof, and a convertible—gleamed in the sunshine, strategically arranged in front of a wooden grandstand that was draped with fresh forest greens from which the party grandees delivered their speeches.”

The Labor Front campaigned to get Germans to join a Volkswagen savings scheme. People stuck red stamps worth five Reichsmarks each in official savings books until they reached the 990 Reichsmarks required to buy a Beetle. Over a quarter of a million people enrolled in less than 18 months.

Impressive though this total seemed, it fell far short of what the regime envisioned. With this level of enrollment, the scheme would never even remotely have covered the costs of production. Most of the savers were middle-class, and a third had a car already; the masses simply couldn’t afford the level of savings required. Moreover, as Rieger points out, the mass reluctance to part with savings reflected anxiety about the Nazis’ increasingly bellicose foreign policy.

ORDINARY GERMANS WERE RIGHT to be skeptical about the savings scheme. No individual who signed up ever got a Volkswagen—at least not from funds invested during the Nazi era. The money went into arms production. So, too, did the factory. Only 630 Beetles were made before the war, most snapped up by regime officials.

In 1939, as the Reich was whisking Volkswagen workers off to labor on Germany’s western fortifications, the Nazis were able to keep production going only by obtaining 6,000 laborers from Italy. They lived in wooden barracks; by September 1939 only 10 percent of the planned accommodations in Strength through Joy City had been completed. The Italians worked to build a military version of the Beetle. The jeep-like Kübelwagen, or “bucket wagon,” saw service wherever German forces operated. The Schwimmwagen was an amphibious variant.

After Germany’s defeat, the factory and company town fell within the British Zone of Occupation. Ivan Hirst, a major in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers Corps, arrived to inspect the plant. He found that 70 percent of its buildings and 90 percent of its machinery were intact. The British Zone had 22 million inhabitants owning a mere 61,000 motorcars, nearly two-thirds of them described as “worn out.” Railway track and rolling stock were in ruins. Needing rapid improvements in transport, the British military government ordered Hirst to restart Beetle production.

Applying ideas and methods derived from British colonial experience in Africa, Hirst set to work, using existing factory staff. When denazification booted more than 200 senior managers and technical experts, Hirst found substitutes or had verdicts overturned, in a triumph of necessity over legality and morality typical of occupied Germany in the late 1940s. He also managed to recruit 6,000 workers by the end of 1946.

But the resurrection had been too hasty. Mechanical and other problems dogged the cars. British auto engineers said the noisy, smelly, underpowered Beetle had no commercial potential. No one wanted to relocate the factory to Britain. So the Germans got the Volkswagen back.

HEINRICH NORDHOFF, A GERMAN engineer for Opel who enjoyed close contacts with that company’s owners in America, General Motors, turned things around. Although not a Nazi, Nordhoff had contributed to the war economy by running the Opel truck factory, Europe’s largest. His extensive use of forced labor denied him employment in the American sector, but the British did not mind. Nordhoff threw himself into the job with manic intensity, working 17 hours a day to streamline production, eliminate technical deficiencies, recruit dealers, and establish effective management. The car came in bright colors, or, as Nordhoff put it, a “paint job absolutely characteristic of peacetime.” Production figures began to climb, and sales started to improve.

But it was not so easy to shake off the automobile’s Nazi past. Strength through Joy City was renamed Wolfsburg, after a nearby castle—though some may have recalled that “Wolf” was Hitler’s nickname among cronies, so the name could be read as “Hitler’s Fortress.”

Wolfsburg was crowded with refugees and expellees from the east—some of the 11 million ethnic Germans ejected from Poland, Czechoslovakia, and other Eastern European countries at the war’s end. Burning with resentment, they proved easy marks for ultra-nationalist agitators. By 1948, the neo-Nazi German Justice Party was garnering nearly two-thirds of the local vote, while vandals repeatedly daubed factory walls with swastikas and many ballot papers were marked with the words “We want Adolf Hitler.” As a new town, Wolfsburg lacked experienced politicians to counter extremist nostalgia. Only gradually were mainstream parties able to push the neo-Nazis back into the shadows.

Heinrich Nordhoff aided in this, insisting that Germans’ travails in the late 1940s were the result of “a war that we started and that we lost.” His frankness had limits: he did not mention the mass murder of Jews or other Nazi crimes. He even echoed Nazi language in urging workers to focus on “achievement”—Leistung—just as Hitler in 1942 had urged “a battle of achievement for German enterprises” in war production.

Whatever the rhetoric, the workers certainly did “achieve.” While the badly damaged Opel and Ford factories were struggling to get production under way, the Volkswagen plant was already turning out Beetles in large numbers. Efficiency rose steadily during the 1950s as Nordhoff introduced full automation on lines pioneered in Detroit.

In August 1955 the millionth Beetle rolled off the line, painted gold, bumper encrusted with rhinestones, before 100,000 onlookers. Twelve marching bands played Strauss tunes, belles from the Moulin Rouge danced the cancan, a black South African choir sang spirituals, and 32 female Scottish dancers performed the Highland Fling to the sound of pipers. Reporters enjoyed lavish entertainment, while the event, and the accomplishments of the Volkswagen factory, were brought to the public in a 75-minute movie.

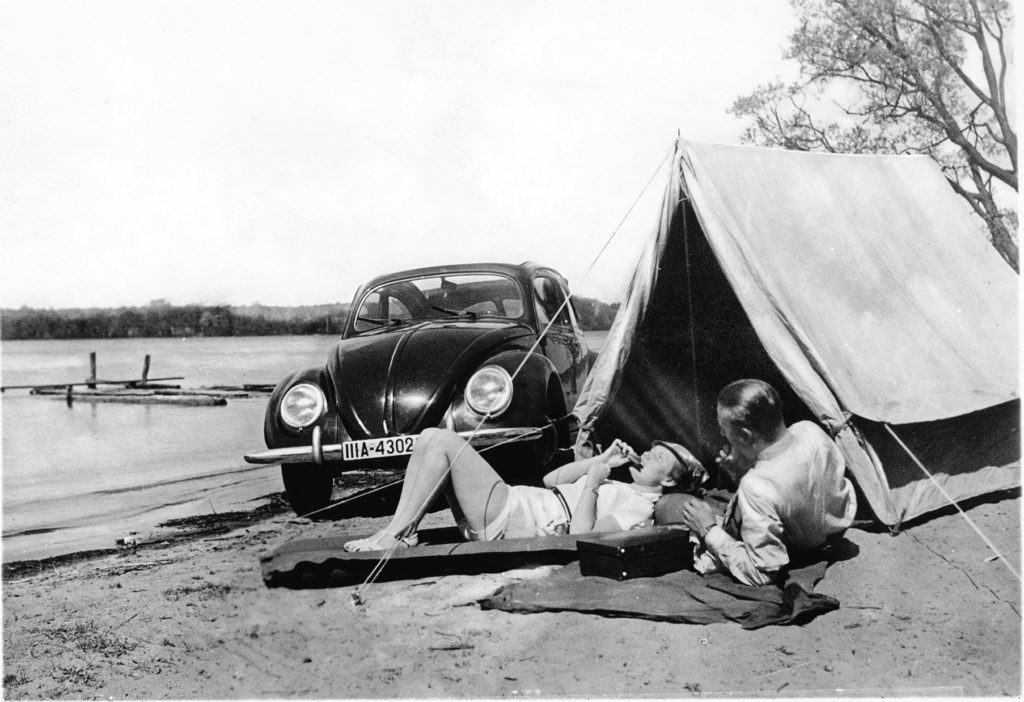

The Beetle achieved iconic status in West Germany as a typical product of the 1950s Wirtschaftswunder, or “economic miracle”—not flashy or glamorous, but solid, functional, dependable, inexpensive to acquire and run, and easy to maintain: everything the Third Reich had not been. As West Germany became a “leveled-out middle-class society,” the Beetle became the leveled-out middle-class car of choice.

Lacking obvious national symbols, Germany west of the fortified border that divided it from the Communist east fixed on the Beetle as an icon. Car ownership suited West German society’s retreat into private and family life in reaction to the Nazi era’s overheated, over-politicized public sphere. The liberty to drive anywhere, whenever you chose, was celebrated as a pillar of Western freedom during the Cold War.

The Beetle’s Nazi associations faded in a historical car wash that ascribed its origins to Ferdinand Porsche’s genius. Veterans fondly remembered driving its cousin, the Kübelwagen. Younger individuals liked the little car’s utilitarian sobriety. The Beetle represented for Germans the “new landscape of desire” of the sober, conservative 1950s.

At the same time, the Beetle was making giant inroads as an export, with an especially fruitful market in the United States. Sales of the Beetle—also called the “Bug”—took off in the U.S. in the mid-1950s. By 1968, Volkswagen was shipping more than half a million Beetles a year across the Atlantic, accounting for 40 percent of production. At least five million Americans bought Beetles. By the 1970s the car had even become a countercultural fixture, with aerospace-engineer-turned-mechanic John Muir’s How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive selling more than two million copies.

Foreign sales sustained the company as Germany’s Beetle era ended. The 1973 to 1974 oil crisis, changing fashions, tough new safety regulations, and failure to maintain the pace of automation caused domestic sales to slump. With the end of the “economic miracle” came the end of the Beetle. West Germans began to demand vehicles that were faster, roomier, more comfortable, more elegant. In 1978 the factory at Wolfsburg stopped manufacturing Beetles.

In 1997, Volkswagen introduced a “New Beetle,” appealing to the American fashion for retro-chic but making clear that this vehicle fully met 21st-century motorists’ demands (“Less Flower. More Power,” one ad put it). Its curving silhouette deliberately invokes the original.

Yet owners of old Beetles know it’s not the same. They rally with their vintage vehicles at locations worldwide to admire antique models and imaginative custom jobs. One meeting has occurred annually since the 1980s in Nuremberg at the scene of the 1930s Nazi Party rallies, in front of the rostrum where Hitler ranted. Nobody seems to notice. The Beetle has long since become globalized, detached for most people from its Nazi origins.

In 1998, New York Times columnist Gerald Posner mentioned to his mother-in-law, whom he described as a “conservative Jew,” that he had bought a New Beetle.

“Congratulations darling,” she replied. “Maybe the war is finally over.”

Adapted from The Third Reich in History and Memory by Richard J. Evans with permission from Oxford University Press, Inc. Copyright © Richard J. Evans 2015. Feature photo: © Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy. Originally published in the May/June 2015 issue of World War II magazine.