Freedom is not something you win once and have forever.

As those who fought in Vietnam continue their 50th anniversary commemoration on Veterans Day this year, the nation also marks the 100th anniversary of the Nov. 11, 1918, armistice that ended World War I. For Gerald York, both of those commemorations are personal.

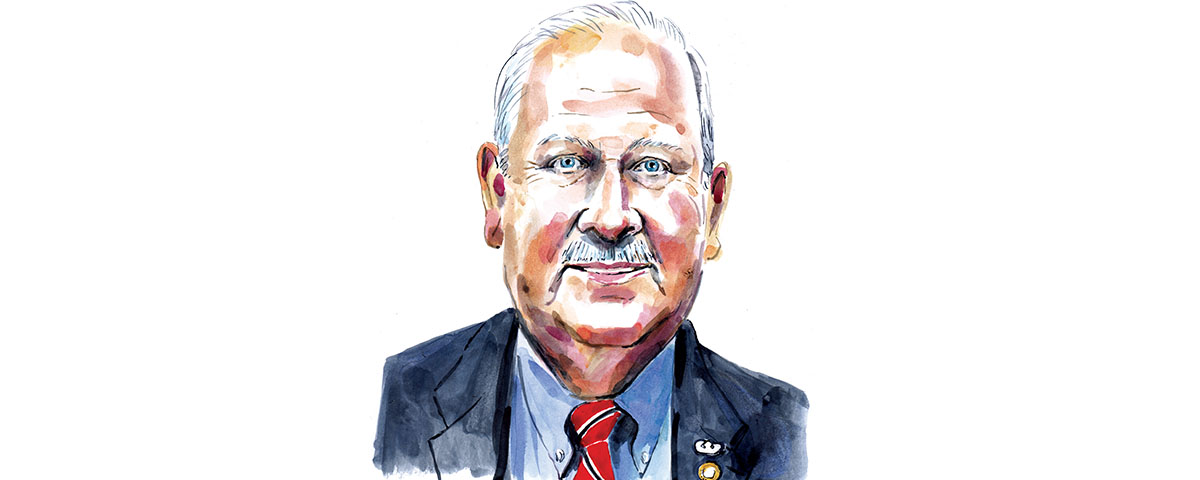

He is a combat veteran of Vietnam and the grandson of Sgt. Alvin C. York, who received the Medal of Honor for sharpshooting that persuaded 132 Germans to surrender to the Tennessean and his seven-man unit on Oct. 8, 1918.

Gerald York, son of George Edward Buxton York, graduated from an ROTC program and volunteered for service in Vietnam, where he was an intelligence officer advising South Vietnamese units in the Phoenix Program, formed to track down and capture or kill top Viet Cong leaders. Later assignments included intelligence officer, 18th Airborne Corps staff, Fort Bragg, North Carolina; base commander for the Defense Intelligence Agency at Fort MacArthur, California, and in Yongsan, South Korea; chief of operations for human intelligence services at DIA offices in Washington.

York retired from the military in 2000 and founded a government services consulting company in Pall Mall, Tennessee. Since 2005 he has been chairman of the Sergeant York Patriotic Foundation, which supports the Alvin C. York State Historic Park and is raising money to establish the Sgt. York Center for Peace and Valor, a multipurpose educational facility.

He shared memories of his grandfather and his own service in an interview with Editor Chuck Springston.

When did you learn that your grandfather was famous? I was in the fifth grade. The teacher called on me one day and said, “I would like for you to come up and get the encyclopedia and look up your grandfather.” I’m thinking, “Why would my grandfather be in the encyclopedia?” I opened the encyclopedia, and she said, “I want you to read what it says.” So I read it to the class and thought, “Wow, my grandfather’s in the encyclopedia.” Even though I’d seen visitors coming in and I knew there was movie [Sergeant York, 1941, starring Gary Cooper] because we had a copy of it, that’s the first time I really realized that he was known outside of our family.

But to me, he was just a grandfather and was always jovial. One time I got in trouble and hid behind him and he wouldn’t let my father spank me. He said, “No, no it’s OK.” He was just a very nice, very good grandfather.

What impact did the knowledge of his fame have on your life? The values he gave me had more of an impact than him being famous. You always told the truth. You always respected others.

Fast-forward to college graduation and service in Vietnam. What was your experience like as an adviser to South Vietnamese troops? I was commissioned on graduation and went into military intelligence. I volunteered to go to Vietnam, but wanted to be with an American unit. When I got there, as a first lieutenant, a major said, “We have a special program in MACV [Military Assistance Command, Vietnam], and we want to make you an adviser.” I said, “Sir, I appreciate it, but I really didn’t volunteer to come over here to observe. I want to be here with an American unit. I don’t want to be an adviser.” He said, “Well, lieutenant, there are sometimes the needs of the Army.” So I went into the Phoenix Program.

They assigned me to Saigon. I was there about four days, and they reassigned me to the Phoenix Program in Loc Ninh district, Binh Long province, up on the Cambodian border. We lived on a compound where we worked with our South Vietnamese counterparts in the Phoenix Program. I guess I had been there about 30 days when we got a major attack and had about a five-day battle. I’m like, “Well, welcome to Vietnam.”

Did anyone know you were related to the World War I hero? Maybe two to three weeks after that battle, I got a call that the colonel wanted me in Bien Hoa [near Saigon]. I’m thinking, “Am I being canned?” I report to the colonel, and he said, “Sit down lieutenant. I’m trying to decide what to do with you.” I said, “Sir, I thought I was doing a decent job.”

“You’re doing an excellent job,” he said. “That’s not my issue. Was your grandfather a medal of honor winner?” I said, “Yes, sir.” He said, “What was his name?” I said, “Alvin York.” He said, “Sgt. Alvin C. York?” I said, “Yes sir.” He said: “That’s what somebody told me. I had a guy in my command whose father won a Silver Star in World War II. He was determined to get a Silver Star. And he did—posthumously. So I need to know, what’s your objective here? You volunteered to come. Why are you here?”

I said, “Sir, I volunteered to come with an American unit because I figured I was going to go to Vietnam sometime. I’m here to serve my country.” He said, “You’re not trying to outdo your grandfather?” I said, “Sir, what my grandfather did, he didn’t set out to do. It was something he did to save lives, not to take lives. It was just the time and the place, and he had the skill sets to accomplish what he did. I could never equal my grandfather. My objective in Vietnam is to do the best job I can do, keep my people safe and go home safe.”

He said, “OK, as long as that’s your objective, you can go back to Loc Ninh. Otherwise, I’m going to keep you in Saigon. You won’t see any action.” And I said, “Well sir, I’m not planning on doing anything crazy.” He said, “OK,” and sent me back to Loc Ninh.

Do you see similarities between World War I and the Vietnam War? In Vietnam and World War I the U.S. was really not prepared. World War I was the first time the U.S. had really gone on the world stage as a power. And in Vietnam we had never fought a war like that. Vietnam was a guerrilla war. We had fought conventional wars. In World War I, Gen. [John] Pershing had to develop tactics [different from those used previously]. In Vietnam, Gen. [William]Westmoreland had to say, we can’t fight this like we fought World War II or Korea; we have to learn to fight differently. Similar to World War I, we had to fight a war like we had never fought before.

We were used to static lines, large numbers of troops attacking an enemy that was dug in and was clear. In Vietnam you could be fighting here, and the enemy could be behind you. The enemy could be the barber that comes in and cuts your hair on Friday and comes back as a sapper [commando] on Saturday night. In World War I you worried about [poison] gas. You worried about artillery. In Vietnam you worried about roadside bombs and ground-up glass that was put in drinks and given to the soldiers. They’d go by your jeep and drop a grenade in the gas tank. There are no similarities in how the two wars were fought but similarities in that they were both an introduction to a different type of warfare.

Apart from the nature of the enemy, are there any other major differences with past wars? When I came back, they told us don’t go outside the airport in your uniform. Don’t let anybody know you’re coming back from Vietnam—because of the protesters. In World War I and World War II people were welcomed back as troops who had defended freedom. In Vietnam, they were seen as baby killers or whatever. I don’t think the country really appreciated Vietnam until recently. It was different for Desert Storm [1991 Gulf War]. And now with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, people are more supportive of the military. During Vietnam, the military was seen as something that was almost evil; today it is seen completely different.

Could anything have been done in Vietnam to make that war turn out differently? I think it could have been different. Every time we started making major gains and the Viet Cong or NVA [North Vietnamese Army] really got hurt, they would ask for a cease-fire and say let’s talk. I was there for a couple of cease-fires. They lasted a couple of weeks, and we would see increased activity, major movements. You couldn’t do anything about it because you’re in a cease-fire. But they used cease-fires to replenish, refresh, resupply, and then once they got built up, they’d attack again.

The military if left to its own procedures could probably have done better, but we were fighting an unwinnable war because it was so political. The time I was there we couldn’t go into Cambodia. We had NVA mass on the Cambodian border. They could come across the border, hit us and go back across the border. You couldn’t follow them.

Should we have taken the constraints off the military and invaded North Vietnam? I think the North Vietnamese were close to a breaking point, and that’s the reason they said [in fall 1972], “Let’s do a peace treaty.” If it looked like we had broken them and were getting ready to invade North Vietnam, I think at that point China would have probably put pressure on North Vietnam to stop and keep a border, like in Korea. It could have remained South Vietnam, North Vietnam.

Is there any military leader that you particularly admire? There are a couple. Gen. Pershing was the right man for the right time. He did an excellent job. Gen. [George] Patton in World War II—he was a little gruff, but as a tactician and as a warfighter was very good. Eisenhower is more of a political general. Patton was more of a soldier’s general. He was one who would go in and win.

The Vietnam era was also noted for its pop culture. Is there any particular music or group that you were interested in? My favorite song when we were in Vietnam was “I’m Leaving on a Jet Plane” [sung by Peter, Paul and Mary]. I hear it today played some, and it brings a lot of memories. Of course, I liked the Beatles back then. Elvis Presley was from Tennessee.

As the World War I commemoration comes to an end, how do you think your grandfather would look back on his war? His thinking was we had gone and won peace [in World War I], won freedom forever. Later in life, as World War II was coming, his thinking changed. We learned that freedom is not something that you win once and have forever. You only get a lease on freedom. We made a payment on it in World War I. Now that the world’s involved again in conflict, it’s time for us to make another payment. Freedom is not something you are guaranteed. Freedom is something that you have to constantly defend.

For more information on the Sgt. York Center for Peace and Valor and its programs for veterans and others, go to www.sgtyork.org.

Residence: Pall Mall

Education: Trevecca College, Nashville, Tennessee, bachelor’s in history, 1969

Military service: U.S. Army, November 1969-December 2000; highest rank: colonel

In Vietnam: November 1970-October 1971; military intelligence officer, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam Advisory Team 47

Today: President, York Consulting Inc., Pall Mall, founded in 2000, provides training and support services to the federal government,10 employees; chairman, Sergeant York Patriotic Foundation