As Robert “Bobby” Phillips and his friends played together after school in Quincy, Massachusetts, nobody in their close-knit hometown could have imagined that one day he would disappear without a trace in Vietnam after being ambushed by the enemy.

Yet 52 years after Phillips’ disappearance, his friends and community still remember him fondly. Their affection for Bobby culminated in efforts to have his name inscribed on the city’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial Clock Tower, despite legal hurdles and the elapse of decades. Their mission was finally realized on June 28, 2022, when the city held a memorial service at the clock tower with Bobby’s name freshly inscribed on it.

A Much-Needed Photo

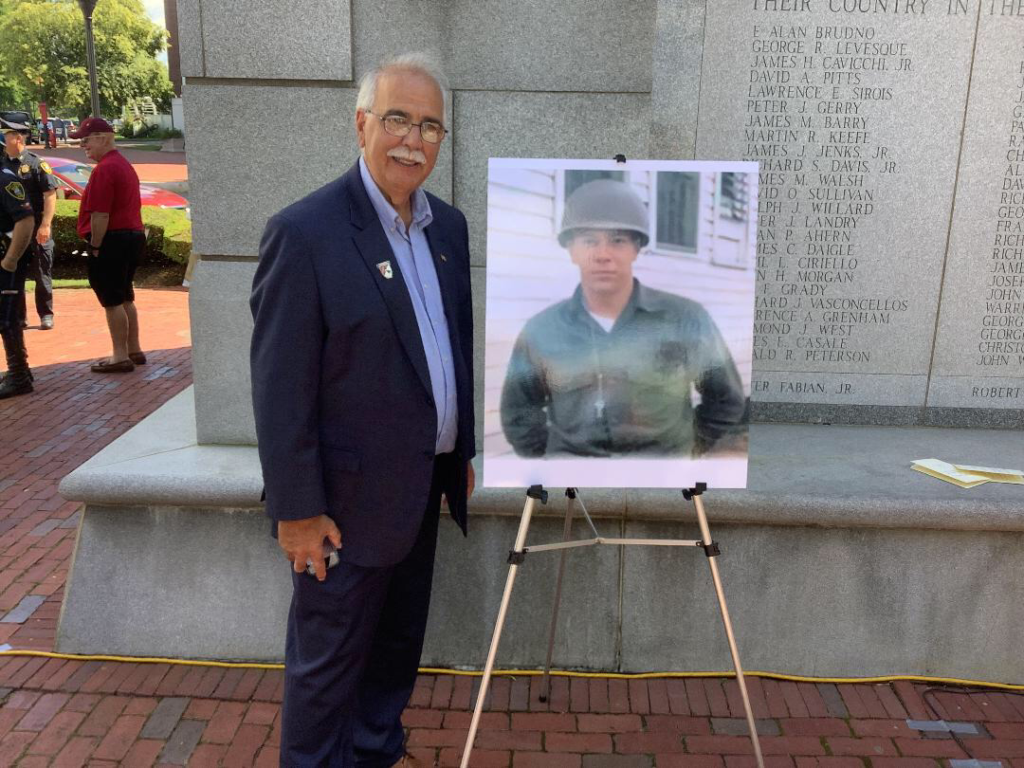

The memorial service was the result of a long journey in which Vietnam magazine played a role. A Vietnam magazine interview with researcher Janna Hoehn enabled Bobby’s friends to obtain a poster-sized photo of him to display at the service.

“I was trying to get a picture of Bobby Phillips for the ceremony we were going to have, so I sent her [Hoehn] an email …. She was really very helpful,” said James Vaughn, one of Bobby’s classmates who also served in Vietnam. “I would never have known about her efforts to get a picture for everybody.”

“People were going up after the ceremony taking their pictures with Bob [next to the poster],” said Vaughn. “That made me feel good — that he was so well-remembered in town.”

Phillips’ name is now publicly inscribed in the heart of Quincy because his friends did not give up on him.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Last Reunion in Vietnam

Founded in 1792, Quincy is known as the birthplace of American patriots John Hancock, John Adams and John Quincy Adams. Vaughn describes it as a place where “everybody knows each other, and everybody’s got a silly nickname.”

Phillips, born in Quincy on July 31, 1949, was known as “Flipper” for his cheerful and boisterous personality.

“He was a bubbly kid. He was always talking in class,” Vaughn said.

John Magnarelli, another friend and former schoolmate, described him as “fun to be with, full of mischief and always getting into trouble.” Phillips eventually relocated out of state with his mother, and his classmates lost touch with him. Then, as fate would have it, he experienced an all-too-brief reunion with Magnarelli — in Vietnam.

“Too many of us went to Vietnam,” said Vaughn, adding that 50 men from Quincy lost their lives in Vietnam. “We died at twice the rate of the United States per capita.”

While Vaughn, drafted into the U.S. Army, found himself at a Marine base at Marble Mountain south of Da Nang, Magnarelli crossed paths with their old friend Bobby again. Magnarelli had just finished his tour of duty in April 1970 and was sitting on the tarmac at Bien Hoa Airbase when a familiar stranger walked back into his life.

“I waited patiently to hop on a Freedom Bird for the trip back to the world when all of a sudden I saw this soldier walking past me, and I instantly recognized Bobby Phillips,” he said.

It turned out that Phillips had not forgotten his time in Quincy. Finishing his second tour of duty, he was due to return to the States in August — and in fact told Magnarelli he was planning to move back to his old hometown. Both old friends were happy to see each other, but standing on the air strip at Bien Hoa, they didn’t have as much time to socialize as they would have wanted.

“We caught up as best we could in the short time we had and vowed to reconnect once he returned to Quincy,” Magnarelli said.

It was the last time any of Phillips’ Quincy friends saw him.

More on the Lingering Memories of Vietnam

The Disappearance

On June 23, 1970, Pvt. Phillips, serving as a truck driver, left Dian for Lai Khe on what should have been a routine supply run. Accompanied by supply sergeant Joe Pedersen and armorer James Rozo, Phillips’ mission was to “update clothing records, retrieve excess equipment, adjust hand receipts” and inventory weapons for two subunits of the 595th Signal Company.

Armed with M-16 rifles and one .45 caliber pistol, the three safely arrived in their 2 ½-ton GMC truck at Lai Khe. But the trip was not over — they still needed to make one last stop before returning.

Danger stalked the road to leading to their final stopover at Phuoc Vinh Signal Site. The usual route was closed off. Mines and booby traps had been discovered on the road, and soldiers were informed that unseen enemies could be lying in wait.

No less than three soldiers at Lai Khe warned SFC Pedersen on two separate occasions of the danger on the route and told him the correct detour to take. Despite this advice, SFC Pederson took his party down the old road. None of the men were ever seen alive again.

The truck that Phillips was driving was found empty in a ditch by the roadside with its engine still running. The windshields had been shattered by bullets. One of the front tires was blown out. A search party found the body of a Viet Cong insurgent who had apparently been killed by a shot from Pederson’s pistol. Three M-16 rifles, all jammed, were also discovered in the area.

Unaccounted For

From that point onward, Phillips’ fate remains undetermined. According to a captured Viet Cong named Tranh Van Thanh, who admitted participating in the ambush to U.S. counterintelligence agents in September 1970, Phillips and Rozo were taken away somewhere in the direction of Cambodia. The Viet Cong alleged that Pedersen had died of natural causes after “refusing to eat.” The captured soldier was unable to lead U.S. soldiers to a burial spot, and his claims were contradicted by a list of names released by the Viet Cong in 1973 of U.S. POWs who had died in captivity.

Another Viet Cong operative, taken prisoner in 1971, testified that he had seen two POWs matching the descriptions of Rozo and Phillips en route to Cambodia.

A U.S. intelligence report released to Rozo’s family in 1985 stated that the two men had attempted an escape in 1972 and that Phillips survived in the jungles for a short period before being recaptured and killed by the vengeful Viet Cong.

“I can’t imagine how frightening it was for him, constantly moving, foraging for food, evading his captors, with nothing but the clothes on his back,” Magnarelli said.

However, none of this information has been conclusively proven — and thus all three men are still listed by the U.S. government as “unaccounted for.”

“His [Phillips’] body was never recovered, and to this day there is still no closure for his family and friends,” Magnarelli said.

Phillips’ memory remains alive in the hearts and minds of those who knew him. His name is now displayed prominently on Quincy’s clock tower memorial.

“Well, Bobby, it’s been a long time. Fifty-two years and you’re 10,000 miles from Quincy,” Magnarelli said in an emotional address at the memorial service. “But welcome home, my friend.”

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.