IN JULY 1298, England’s Edward I met an army under the Scottish rebel William Wallace at Falkirk, in the central lowlands of Scotland. Between a small swamp and a forest, amid the mud and the screams, Edward defeated the warrior of Braveheart legend in one of the major battles of the First Scottish War for Independence.

Thanks to Edward’s ingenious tactics, the Scottish spearmen ‘fell like blossoms in an orchard,’ an English chronicler later exulted

It was a clash where the old began to give way to the new. History knows Edward as a great ruler and one of the best field commanders of the medieval world. But he was also a military innovator. Under his heavy hand, the English army was transformed from an ill-disciplined and disorganized lot into an efficient fighting force—a forerunner to the modern army. Paid military regulars, a chain of command, tight discipline, an emphasis on infantry over cavalry—all were on display at Falkirk, and all would grow and help secure English victories in coming centuries.

The battle at Falkirk was a clash that brought to a head more than a decade of turmoil. The Scottish king Alexander III died in 1286 with no clear heir, throwing the country into chaos. Fearing bloodshed, the Scots eventually asked Edward to arbitrate and choose among the claimants to the throne. The king agreed, but only on the condition that Scotland’s new ruler recognize him as feudal overlord. William

Wallace and others opposed these terms, but the rivals to the throne complied (perhaps influenced by a show of English military might).

In 1292, Edward made his choice—John Balliol, a lord of Galloway who had been loyal to Edward’s father, King Henry III. Almost immediately, however, Edward stirred up trouble for the new ruler. He ousted Scottish officials and selected their replacements, meddled in legal affairs, and demanded support for a military campaign he was waging in France. Infuriated, the Scots rebelled in 1296, with Wallace, a knight and prominent landowner, inspiring a surge of nationalistic pride.

Edward, who was campaigning in France, delegated a force to march north and resolve the “Scottish problem.” In September 1297, however, Wallace joined fellow knight Andrew de Moray to attack and soundly defeat a larger English force at Stirling Bridge on the River Forth in Scotland. Though outnumbered, the two outwitted their enemy: After an English vanguard of a couple of thousand men had forded the narrow crossing, the Scots charged, captured the bridge, and encircled them. Unable to send enough reinforcements across the bridge, the English retreated and left their brethren to the mercy of their foe. The battle inspired the Scots and helped make Wallace the de facto ruler of Scotland. (Mel Gibson’s 1995 Braveheart recreated the battle, though the screen version looked nothing like the original.)

With that defeat, Edward hurriedly concluded a truce with the French and returned to England to mount a new invasion against the scrappy rebels. Traditionally knights were recruited through a feudal summons that required 40 days of military service from the king’s vassals. Though Edward would use the summons until the end of his reign in 1307, he chafed at its unpredictability; he never knew how many men would answer his call, and he had no means to ensure their cooperation.

The idea of paying knights and soldiers for their service had been suggested as early as the eighth century. Mercenaries, or “free troops,” as they were often called, had figured in European armies from at least the early 12th century. Edward had tried to field a paid force in 1282 when he snuffed out a Welsh rebellion, but many nobles had balked, fearful that accepting pay subordinated them to the king.

Fifteen years later, as Edward prepared his invasion of Scotland, such resistance had weakened; paying soldiers was becoming a more common practice in Europe as central governments grew in power. Of the 2,200 knights Edward recruited for his army, some 1,200 were paid. Knights in command who were members of the titled aristocracy received four shillings a day; other knights received two shillings.

More than half of the foot soldiers Edward mustered were also taking wages—two pence a day. Previously, medieval infantry had been poorly armed, disorganized, and undisciplined peasants. But when paid they proved more dependable, better disciplined, and less likely to abandon a long campaign. Longbowmen collected the same pay as other infantry, but crossbow archers made four pence a day, the equivalent of what a skilled tradesman earned in civilian life.

IN ALL, the army that marched into Scotland in 1298 totaled about 15,000 men—the largest army in English history to date. It was undoubtedly a grand sight. Contemporary sources describing an English campaign soon after said Edward’s mounted knights were “well armed and mounted on costly great horses….There were many rich trappings of embroidered silks and satins, many fine pennons on lances.”

Early in July, Edward visited the shrine of Yorkshire’s John of Beverly, a saint beloved by the army, and then advanced into Scotland. Wallace’s force retreated north, staying just ahead of Edward and laying waste to the countryside as it moved. Wallace hoped to avoid battle until English supplies and money ran low; when Edward was forced to withdraw to resupply, the Scots would attack.

Edward had just left his camp near Edinburgh and was returning to the city for provisions when he learned that Wallace’s troops had taken up a position at the wood of Callendar, near Falkirk and northwest of Edinburgh.

“I will meet them this day,” he said.

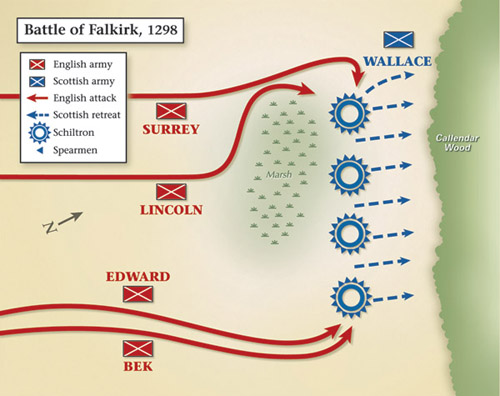

The English army turned toward Falkirk. On July 22, Edward saw the enemy, “many spearmen on the brow of the hill,” as one chronicler wrote. Unlike their earlier battle at Stirling Bridge, the Scots set up a defensive position, creating four great circular formations known as schiltrons, each with about 2,000 spearmen, their 12- and 14-foot wooden pikes with iron tips pointed outward at various heights. One source says rope was strung up on stakes around the schiltrons as a defense and to keep them in place. Some 1,500 longbowmen filled the spaces between the schiltrons. About 500 cavalry were posted in the rear of the formation. In all, the Scottish force may have totaled 9,000 or 10,000 men.

Edward’s cavalry was divided into four battalions. The king commanded the 3rd Battalion in the center and to the rear of the two wings. Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln, led the 1st Battalion; John de Warenne, 7th Earl of Surrey, commanded the 4th. Together they marched on Edward’s left while the 2nd Battalion under Anthony Bek, the bishop of Durham, was on his right. Once they spied the enemy, Lincoln and Surrey attacked but were forced to loop around a small marsh before they could hit Wallace’s right. Seeing this, Bek wanted to hold back to allow the king to get into position. But he was overruled by his knights, who were anxious to join their comrades.

Both wings of the English cavalry closed on the Scots in a disorganized charge. Such attacks were typical of the undisciplined, glory-hungry medieval cavalry in Europe; these men prized courage and determination over discipline and coordination. “When the enemy came into sight,” one historian writes, “nothing could restrain the western knights; the shield was shifted into position, the lance dropped into rest, the spur touched the charger, and the mailclad line thundered on, regardless of what might be before it.”

This initial charge, however ill considered, had the desired effect: The Scottish cavalry fled the field, hardly engaging the enemy. (Some have speculated that agents of Edward had engineered this retreat with well-placed bribes. Others suggest the Scottish aristocrats wanted to sabotage Wallace, as he had not been born to nobility.) The Scottish bowmen, stationed between the schiltrons, stood their ground, though many were quickly cut down by the onrushing knights.

Despite these setbacks, the schiltrons held firm, absorbing the shock of the charge. The English charge began to dissipate. Some knights were trapped under their fallen horses; at least one, a chronicler wrote, charged “hotly and rashly” against the Scottish formations. Chaos ruled amid the cries of pain and the clash of swords. The surviving Scottish archers launched shafts into the melee while English crossbowmen fired bolts into the forest of schiltron spears.

EDWARD ARRIVED at the battle after his wings. With his knights struggling against the long spears, he called back his impetuous heavy cavalry. Restoring discipline and a centralized command, he regained control of the battle.

First, Edward brought in the longbows from his infantry. Aided by crossbowmen and Irish slingers hurling stones, they quickly overcame what was left of the Scottish archers. The longbows and crossbows then turned on the schiltrons, which had been left defenseless by the flight of the Scottish cavalry. The Scottish spearmen “fell like blossoms in an orchard,” an English chronicler later exulted. With the Scottish ranks now thinned dramatically, Edward released his cavalry. The knights who had opened the fight so poorly now finished it off in victory.

Edward suffered about 2,000 casualties among his infantry. A single knight and five of his retainers were killed. Wallace suffered a similar number of casualties. He and others escaped into a nearby forest, but his reputation and influence were destroyed. In 1305, he was captured near Glasgow, handed over to Edward, and executed.

Edward pursued the fleeing Scots until a shortage of supplies forced him to retreat, largely ending the campaign. But his innovations—especially the use of wages—had begun the process of converting the feudal host into the disciplined, professional army that would later prove itself at Agincourt and Crécy and then later at Waterloo, Quebec, and Normandy. It would be nearly 350 years before the English Civil War led to the creation of England’s vaunted New Model Army, but the day of the armored knight “hotly and rashly” charging at the enemy was coming to an end.

Chuck Lyons, a frequent contributor to MHQ, wrote about the dominance of the longbow in the Summer 2010 issue.