![In 1952 Clyde Forsythe painted "Gunfight at O.K. Corral, based in part on stories from eyewitnesses—including his own father. [Image: © Lee A. Silva Collection]](https://www.historynet.com/wp-content/uploads/image/2013/WW/OCT/Forsythe%20final%20painting.jpg)

Forsythe’s depiction of the Gunfight at O.K. Corral may just be the closest thing we have to an actual photograph of the event.

The list of luminaries associated with artist Victor Clyde Forsythe is as long as it is unlikely, ranging from Theodore Roosevelt and Bat Masterson to William Randolph Hearst, Norman Rockwell, Walt Disney, and Babe Ruth.

The “First Generation” desert painter and cowboy artist holds a few other surprises on his resume, including the fact that in the early 1940s he contributed to the U.S. war effort by developing a device used to assess a rare mineral used in gun sites.

Most relevant to fans of the Wild West, however, is his depiction of the Gunfight at O.K. Corral—a painting that may just be the closest thing we have to an actual photograph of the event.

It was in mid 2010 when historian and antique dealer Lee Silva “stumbled upon” and purchased a collection of paintings, drawings, letters, and personal belongings of many of the early cowboy desert painters including Victor Clyde Forsythe, John Hilton, Bill Bender, James Swinnerton, Ettore “Ted” DeGrazia, Will James (see Silva photo, Wild West, October 2012; page 16), Ed Borein, and Olaf Wieghorst. Lee had been called out to a diminutive isolated desert community in Southern California to appraise a cache of old Western photos that had turned up in the estate of Western painter Clyde Forsythe. The hundreds of unlabeled photos of “cowboys” at an Old West jackpot rodeo in the 1930s did not seem to have any particular significance. Silva noticed, along with several paintings and letters that were also with the photos, an original, signed pen-and-ink schematic of the well-known 1952, 43-inch by 60-inch oil painting by artist Victor Clyde Forsythe of the Gunfight at O.K. Corral. This unique, one-of-a-kind diagram may be the only one in existence; more than likely Forsythe’s own personal draft of the final painting.

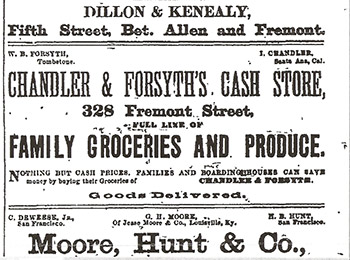

A student of the Old West for more than 40 years, and author of several books and articles, Silva is ![In mid-2010, author Lee A. Silva found an original, signed pen-and-ink schematic of the "Gunfight at O.K. Corral," which identifies each of the men portrayed. [Image: © Lee A. Silva Collection]](https://www.historynet.com/wp-content/uploads/image/2013/WW/OCT/schematic.jpg) considered an authority on the gunfight, has written two books on Wyatt Earp, and is currently putting the finishing touches on a third. This was an extraordinarily significant find, as Forsythe’s father, William Bowen “W.B.” Forsyth (he spelled the name without the “e”) and uncle, Ira Chandler, claimed to have actually been present in Tombstone on that fateful day (October 26, 1881) to witness the gunfight. Their store, Chandler & Forsyth C.O.D., was located at 328 Fremont Street (after having moved from its original location on Allen Street), only a few doors east of the street fight that occurred just west of the back entrance to the O.K. Corral. This store was directly across the street from the Tombstone Epitaph office and next to the post office on Fremont. Forsythe had heard stories throughout his life, from his parents and uncle, about what they (and their Tombstone friends) had allegedly observed October 26, 1881. His father and uncle were said to have kept a diary and recorded what they had witnessed. Clyde studied this journal and visited Tombstone in preparation for his painting and included his uncle, father’s, and other eyewitness accounts. It has been called the closest thing we will ever have to a photograph of the clash; “a frozen moment of history.”

considered an authority on the gunfight, has written two books on Wyatt Earp, and is currently putting the finishing touches on a third. This was an extraordinarily significant find, as Forsythe’s father, William Bowen “W.B.” Forsyth (he spelled the name without the “e”) and uncle, Ira Chandler, claimed to have actually been present in Tombstone on that fateful day (October 26, 1881) to witness the gunfight. Their store, Chandler & Forsyth C.O.D., was located at 328 Fremont Street (after having moved from its original location on Allen Street), only a few doors east of the street fight that occurred just west of the back entrance to the O.K. Corral. This store was directly across the street from the Tombstone Epitaph office and next to the post office on Fremont. Forsythe had heard stories throughout his life, from his parents and uncle, about what they (and their Tombstone friends) had allegedly observed October 26, 1881. His father and uncle were said to have kept a diary and recorded what they had witnessed. Clyde studied this journal and visited Tombstone in preparation for his painting and included his uncle, father’s, and other eyewitness accounts. It has been called the closest thing we will ever have to a photograph of the clash; “a frozen moment of history.”

In April of 2012, Lee Silva and I paid a research visit to the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana, California to view ![]() and compare a preliminary version of Forsythe’s gunfight oil painting (see Wild West, October 2012, Page 34, and October 2013, Page 1) to Lee’s schematic and the final painting. This one, much more basic and sparse in design, includes a statement on the back by Forsythe’s widow, Cotta, that the painting is authentic and was done “after many years of research along with two pencil drawings in preparation for the final and larger work” of the gunfight and two-story Chandler and Forsyth(e) Merchandise.

and compare a preliminary version of Forsythe’s gunfight oil painting (see Wild West, October 2012, Page 34, and October 2013, Page 1) to Lee’s schematic and the final painting. This one, much more basic and sparse in design, includes a statement on the back by Forsythe’s widow, Cotta, that the painting is authentic and was done “after many years of research along with two pencil drawings in preparation for the final and larger work” of the gunfight and two-story Chandler and Forsyth(e) Merchandise.

Of further significance is the fact that the original work of art itself had disappeared after it was first sold at the Biltmore Art Gallery (“salon”) of Los Angeles (co-founded by Forsythe and Frank Tenney Johnson) in the mid 1950s, until it turned up in a private collection in 1966. Therefore most historians never had access to this significant depiction of the street fight prior to this time. In a February 1966 newspaper article appearing in The Register (Orange County) relating how the gunfight masterpiece was recovered, it was claimed, “Clyde Forsythe returned [to Tombstone] years later [after the gunfight], studied the structure of every building, inside and out, interviewed people who witnessed the blazing gun battle and completed many preliminary sketches before he arrived with the final draft.” In the same article, an art authority who knew Forsythe called the depiction a “huge art masterpiece” and when interviewed declared, “I would certainly rank it with the other great works of the American West like Custer’s Last Stand and the Pony Express—indelible imprints of our heritage.”

A limited edition (390 copies) reproduction of the final painting was printed in May 1988 and sold to the general public making it more readily available after this date. Although the oil painting has now been back in the public eye for many years, the participants were not labeled (they were listed in a 1952 edition of Tucson Magazine, just after the painting was completed) and it was left to the observer to decide who was who. In the cartoon-like original schematic Silva discovered (a contemporary and much more basic line drawing was fashioned to be sold along with the 1988 reproduction), all combatants and observers in the drawing are actually numbered and labeled and eyewitness R.F. (Ruben Franklin) Coleman is included (see Silva article, April 2012 Wild West, P. 10).

In the details

It was Coleman who, prior to the gunfight, warned Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan and subsequently deputy U.S. (and town) Marshal Virgil Earp that the Cowboys were in town, up to no good and needed to be contained. For many years, however, historians have debated his presence at the fight and his inconsistent recollections of it. Neither side of the warring parties called Coleman to testify in Judge Wells Spicer’s preliminary hearing. Although Coleman was deemed a “Cowboy supporter,” his initial, and likely most honest, statements in the October 27 issue of the Tombstone Epitaph were damaging to their case: Tom McLaury had fired a gun; Billy Clanton and one of the McLaurys fired first as Virgil ordered them to raise their hands. Just a day later (after the rustler contingent had had a chance to speak with him), during the coroner’s inquest (recorded in the “tainted” Hayhurst transcription), Coleman recalled new details potentially damaging to the Earps: Tom McLaury may not have had a gun, and the witness was now “confused.” It is worth noting that Forsythe does portray Tom McLaury holding, and firing, a gun while shielded by Billy Clanton’s horse, just as the Earps stated and contrary to what the Cowboy faction and Earp detractors have argued over the years. Moreover, Billy Claiborne (“Arizona’s Billy the Kid”) is depicted as a fifth member of the Cowboy contingent. Although Forsythe shows him fleeing, as has previously been well documented, Claiborne is assisted to safety (to Camillus Sidney “C.S.” Fly’s photo studio, a position from which he could back-shoot at the Earp party, as Wyatt later claimed) by none other than Behan, a bitter Earp/Holliday enemy. Whether or not this is actually what Forsythe’s father, uncle, Tombstone friends and the other eyewitnesses he interviewed truly observed and documented, or was added for dramatic and artistic effect, will probably never be known, unless W.B. Forsyth’s/Ira Chandler’s purported diary turns up.

Other pertinent, but subtle findings which can be intuited from Forsythe’s work are Billy Clanton wielding a gun with his left hand, having been wounded in the right wrist; Frank McLaury holding his abdominal wound (one he most likely received from Wyatt or Doc at the very onset of the encounter) as he stumbles north across Fremont Street and takes aim at Doc Holliday; both Doc (with a rifle/shotgun) and Morgan Earp aiming at Frank, Morgan on the ground and aiming at Frank’s head; Ike Clanton making a run for it and obstructing Wyatt in the meantime. Not too bad, given that this painting was completed in 1952 (with the preliminary drawings and research involved many years before that) and the fact that we know so much more today than Forsythe could have possibly had access to then had he not received “inside information”— information that modern day historians may now need to scrutinize more seriously.

Although this painting was completed before the popular Wyatt Earp television show The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp (which ran from 1955 through 1961) first aired, it was painted after Walter Noble Burns (Tombstone— An Iliad of the Southwest) and Stuart Lake’s (Wyatt Earp Frontier Marshal) landmark books, and one could argue that Forsythe’s presentation of the battle may have been tainted by these publications. Stuart Lake was given a “personal tour” of the original painting by Clyde Forsythe himself in May of 1954, but it is known that they had never met until 1953; well after the painting was completed and therefore one cannot claim that Lake, at least in person, fed Forsythe the facts on which he based his painting. Although we will probably never know with complete certainty, Forsythe’s meticulous approach to his paintings, his personal character, and the fact that he prided himself on precision to his subjects, suggest it is unlikely he would use second- and third-hand accounts found in books, movies and television shows as the basis for his rendering. His travels to Tombstone to interview other old-timers who had witnessed the event, and to study every inch of the gunfight site itself, as well as the stories of his father, uncle and their Tombstone acquaintances, bear witness to his thorough approach. An article that appeared in the March 23, 1955 issue of the Los Angeles Times newspaper, written about Forsythe’s Gunfight at O.K. Corral painting, mentions the “painstaking research” that went into his portrayal.

That having been said, Forsythe did admit to taking a couple “liberties with the facts,” mainly moving his family’s store a few doors to the west so he could place it next to Fly’s studio and thereby include his father and uncle in his depiction. Lake would write in 1953 that “Clyde had to telescope and shift some to get the characters on canvas…” As the actual location of the gun battle was still under debate at the time of Forsythe’s late-1940s research for the painting (the city would officially mark the spot as the Fremont entrance to the O.K. Corral until the early 1960s), and as Forsythe’s father and uncle were no longer living to assist him, there are also a few very minor site/landscape errors, but otherwise this rendering is deemed to be consistent with the facts as they are currently known (Lee Silva article; Wild West, April 2012, P. 10).

Recent research into the W.B Forsyth and Ira Chandler (Clyde’s maternal uncle) families make it difficult to believe that their C.O.D. store in Tombstone, where customers could receive a 10 percent  discount for

discount for ![]() paying all cash, was actually located at the 328 Fremont Street location at the time of the gunfight. The store was first located at 404 Allen Street (on the south side, across the street from the Bilickes’ famed Cosmopolitan Hotel, between Fourth and Fifth streets and just a block west of the site from which Virgil Earp would be ambushed on December 28, 1881) before having moved to the Fremont Street location around March 1, 1882, well after the gunfight, but before Morgan Earp was murdered by ambush on March 18, 1882. There is no question they were in town while the Cowboys and Earp’s were still living there.

paying all cash, was actually located at the 328 Fremont Street location at the time of the gunfight. The store was first located at 404 Allen Street (on the south side, across the street from the Bilickes’ famed Cosmopolitan Hotel, between Fourth and Fifth streets and just a block west of the site from which Virgil Earp would be ambushed on December 28, 1881) before having moved to the Fremont Street location around March 1, 1882, well after the gunfight, but before Morgan Earp was murdered by ambush on March 18, 1882. There is no question they were in town while the Cowboys and Earp’s were still living there.

Newspaper reports confirm that the store had opened by February 6, 1882 and that a sister branch was operated in Santa Ana, California by Ira. He ordered the fresh fruit and vegetables and had them shipped daily to W.B. in Tombstone. Forsythe himself never actually claimed that his family’s store was located at the Fremont Street location at the time of the gunfight, only that they witnessed it. In a letter that Earp biographer Stuart Lake (who in the early 1900s was working in New York at the Bennett Herald while Forsythe was there working at the New York World) wrote to historian Robert N. Mullin soon after meeting Clyde for the first time in 1953, he stated that he did not feel Forsythe’s father and uncle actually observed the gunfight themselves, using as his reasoning the fact that they were not called to testify in the Spicer hearing as they most certainly would have had they been eyewitnesses. This logic is not sound, as it is well known that many individuals who witnessed the gunfight were not called to testify, including R.F. Coleman. Lake did claim they saw “goings and comings” relating to the encounter and that they “did testify before the grand jury” which convened in December 1881 after Judge Spicer’s’ decision, and also refused to indict the Earps and Doc Holliday. In 1916 Mullin had sketched a map of Tombstone (based partially on statements of “pioneer Tombstone citizens” as the “deed records,” “fire insurance maps,” and “Nugget and Epitaph” ads he reviewed “were not accurate sources”), at about the time of the gunfight (“circa 1881-‘82”), which was subsequently formalized by Earp historian and collector extraordinaire John D. Gilchriese and published in 1971. It included the Chandler and Forsyth C.O.D. store (“1881”) on Fremont Street.

Further research reveals that Clyde’s parents arrived in San Diego, California on a trip from the east about November 1, 1881; this would place them in the Tucson/Tombstone area about the time of the gunfight. They were traveling to his other maternal uncle Burdette’s home in Los Angeles, California where it is documented they arrived before November 4, 1881. Although it is cutting it somewhat close, it is certainly possible that they witnessed the gunfight as claimed, as they were definitely in the vicinity. Forsythe’s Uncle Ira’s location at the time of the gunfight has not been firmly established, although there is a fair possibility that he was in town exploring sites for their store and home and witnessed the gunfight as stated. Either way, it is more than likely that Clyde’s parents, W.B. and Alice Forsyth, and uncle Ira Chandler, were in Tombstone by very late 1881 or early 1882 as they would almost certainly have scouted out the town well before they actually opened their store there.

An artist’s landscape

The talk of the town at that time most certainly had to have been the ongoing troubles between the Earp/Holliday and rustler factions, and one would expect that they were privy to inside information from those townsfolk they knew and befriended and who had witnessed the confrontation, and even the surviving participants of the battle. In later years, W.B. Forsythe and Ira Chandler lived and worked in the Los Angeles area and had access to the “Tombstone hub” of ex-residents who had relocated there, including the Earp brother’s themselves, John Clum, George Parsons, Carl and Albert Clay “A.C.” Bilicke, Doc Goodfellow, Richard Gird, the Schieffelin, Hooker, and Blinn families, and others. W.B. and Ira knew all the locals and were well immersed in their saga, just as the young Clyde would later become; more than likely often sitting around with his parents and their acquaintances and listening to their stories (probably over-and-over) of their glory days in Tombstone. In his celebrated book, The Cowboy in Art, author and close Forsythe friend Ed Ainsworth would write “The talk about Tombstone and other centers of the cowboy-gunman era sank into Clyde’s consciousness from the moment he was old enough to listen.”

Forsythe and Chandler also most certainly spent time at Carl (mining partner of Wyatt Earp in Tombstone) and A.C. Bilickes’ downtown Los Angeles Hollenbeck hotel and later A.C.’s Alexandria just a few blocks away; known gathering places of the Tombstone crowd in the late 1800s and early 1900s. A.C. even advertised the fact (in Tucson and Tombstone newspapers of the time) that the Alexandria was “the stopping place for Arizonians” when in Los Angeles. The Alexandria Hotel was famous for the fireproof technology employed in its construction; something A.C. was obviously keenly concerned about after his father’s renowned Cosmopolitan Hotel (“the finest building in Tombstone,” according to some observers) at 409 Allen Street burned to the ground in the devastating May 1882 Tombstone fire, which also destroyed the Chandler and Forsyth store. After the O.K. Corral gunfight in 1881, the Earp families would make the Cosmopolitan their home and the wounded Virgil Earp would testify in Judge Wells Spicer’s hearing from his room there. Famed gunfighter Buckskin Frank Leslie lived in the Cosmopolitan and it was there (on the balcony) that he was involved in the shooting (and killing) of Mike Kileen in 1880. A.C. was in the hotel at the time and was called to testify in the ensuing trials. In November 1881 he would once again be called to testify in the proceedings of another historic event, this time in the Clanton/McClaury murder hearing. He subsequently became one of the first casualties of World War I when he died on the Lusitania after it was hit by a German torpedo and sank on May 7, 1915. With the constant exposure to the abundant Tombstone pioneers that his parents associated with, Clyde would become an authority on the Tombstone gunfight to the degree that Earp biographer Stuart Lake himself sought him out in 1954 to view his painting and in Lake’s own words jointly “come up with the low down on the battle” for the Los Angeles Times newspaper.

Evolution of a desert artist

Victor Clyde Forsythe was born August 24, 1885 in the city of Orange in Orange County, California, just south of Los Angeles County, on the site where the Orange City Hall now stands. His father W.B. (and mother Alice Chandler-Forsyth) loved the desert and in 1885 took a series of photos in Agua Caliente, an Indian area about 100 miles east of L.A. and now known as Palm Springs, to show his friends what an “oasis” in a desolate area looked like. The photos survived and in later years were exhibited in a museum where they were used to preserve history and to teach children in the mid 1900s about a beautiful open locale now long gone after modern day civilization had encroached upon it. The family subsequently moved to Figueroa and 8th Street, in what is ![Ed Ainsworth took this photograph of Clyde Forsythe in front of one of his desert paintings. [© David D. de Haas, M.D. collection]](https://www.historynet.com/wp-content/uploads/image/2013/WW/OCT/Forsythe%20artist.jpg) now downtown Los Angeles, in the 1890’s. As a young child in the late 1800s, Clyde, as he was called by friends and family, would vacation with his parents in the California deserts where he, like his father, would learn to appreciate the serenity and beauty of an area many others hated and feared. One particular 1899 camping trip with the entire family made by covered wagon from Orange, California to his uncle’s homestead in Elizabeth Lake, located on the San Andreas Fault northwest of Los Angeles (taking 4 days each way), made an everlasting impression on the then 14-year-old Forsythe. On the trip he was assigned the chore of hunting to provide the daily meals for this large party, which mainly consisted of young children. In later years he would claim “That trip was what got me into the desert and the desert into me.” His other maternal uncle, Burdette Chandler, became an influential man in Southern California and was known as the “Father of oil in California” after having been the first man to dig an oil well in Los Angeles. He subsequently lost most of his holdings to Standard Oil Co. during a late-1800s depression.

now downtown Los Angeles, in the 1890’s. As a young child in the late 1800s, Clyde, as he was called by friends and family, would vacation with his parents in the California deserts where he, like his father, would learn to appreciate the serenity and beauty of an area many others hated and feared. One particular 1899 camping trip with the entire family made by covered wagon from Orange, California to his uncle’s homestead in Elizabeth Lake, located on the San Andreas Fault northwest of Los Angeles (taking 4 days each way), made an everlasting impression on the then 14-year-old Forsythe. On the trip he was assigned the chore of hunting to provide the daily meals for this large party, which mainly consisted of young children. In later years he would claim “That trip was what got me into the desert and the desert into me.” His other maternal uncle, Burdette Chandler, became an influential man in Southern California and was known as the “Father of oil in California” after having been the first man to dig an oil well in Los Angeles. He subsequently lost most of his holdings to Standard Oil Co. during a late-1800s depression.

Clyde’s illustrations in his high school (Harvard Military School of Los Angeles) magazine landed him a job at the Los Angeles Examiner in 1903 and in that same year he began studies at the Los Angeles School of Art and Design where he trained under cofounder Louise Garden MacLeod, who herself had trained in Paris under James Abbott MacNeill Whistler (of “Whistler’s Mother” fame). It may have been in his blood, as the 1860 United States Federal Census lists his paternal grandfather as a (house) “Painter” born in New York. In addition to his grandfather, his great grandfather (George), and even father W.B. were house painters at various times in their careers. In October 1904, at the age of 19, encouraged by his art instructors as well as his parents who saw his potential, he left by train for New York to pursue his studies further at the esteemed Art Students League. He helped pay for his art school expenses ($6 a week tuition) by posing as an art model and then began working for Joseph Pulitzer at the New York World newspaper as an illustrator and cartoonist. Shortly thereafter, at age 20 on June 12, 1906, he married Cotta Owen of Los Angeles (by way of Denver, Colorado). Her father was interested in mining and exploration and was at one time president of the Jerome Copper Mining Company of Arizona. He was a practicing attorney and judge in Denver, Colorado before their move to Los Angeles where he subsequently practiced law for decades.

For the next five years Clyde illustrated fights and other sporting and newsworthy events. In those days newspaper photos were not yet practical or commonly used, although famed newspaper publisher and creator of the world’s largest newspaper chain, William Randolph Hearst, had in essence pioneered the idea in the 1890s. He also began what would turn out to be a 33-year comic strip career and even had bit parts in several early silent movies, at one point even portraying a cartoonist. A 1937 newspaper article stated that “Vic took the hint, stopped impersonating a cartoonist, (and) became one.” Early strips included The Great White Dope and Tenderfoot Tim. In later years he would create what would become his best known and signature strip Joe’s Car (in 1911) and this evolved to Joe Jinks in 1928. Others would include Dynamite Dunn, The Little Woman, and, in 1933, Way Out West.

As implied above, in the early 1900s Forsythe began to achieve great success and was recruited by publisher William Randolph Hearst (who early on had also employed writers Mark Twain, Jack London, and Ambrose Bierce, as well as George Herriman (Krazy Kat) as an illustrator and cartoonist) to work as a cartoonist for the New York Journal and a host of other Hearst syndicated papers. He illustrated articles for Arthur Brisbane, editor of the New York Journal, whom Hearst had also recruited. (After Brisbane’s death Hearst called him “…the greatest journalist of his day” and writer Damon Runyon called journalism’s “all-time Number 1 genius.”) It was at this time Forsythe met and became close (and lifelong) friends with another of Hearst’s cartoonists, Jimmy Swinnerton, known as “America’s Foremost Cartoonist,” the “Granddaddy of the Cartoonists,” the “Dean of the Hearst Cartoonists,” and the father of the modern day comic strip after sketching the first known continuing newspaper comic for Hearst at the young age of 17, beginning in 1892. Swinnerton attended and covered the Fitzsimmons-Sharkey fight in San Francisco in 1896 for Hearst’s Examiner. This well-known clash was refereed by Wyatt Earp and ended in controversy when Earp awarded the fight to Sharkey on a technicality. Swinnerton was friends with Sharkey and apparently knew Earp, too, through the circle of friends and fighting crowd they both associated with. William Randolph Hearst himself was known as a trendsetter on so many fronts, three of which were assisting Swinnerton fashion the first newspaper comic strip and subsequently the first (now commonplace) Sunday morning newspaper cartoon supplement, and also pioneering the use of newspaper photography (in lieu of illustrations) to enhance his stories.

Throughout World War I Forsythe expressed his patriotism by crafting many wartime posters, the most famous of which (“And They Thought We Couldn’t Fight”) pictures a fatigued but victorious American Doughboy collecting German souvenirs after battle. This depiction, said to be a favorite of General John Joseph “Black Jack” Pershing himself, was displayed on billboards throughout the country and subsequently throughout occupied Germany.

While living and working in New York, Clyde achieved significant wealth and distinction. It was during these years that he befriended some of the most famous and influential men of that era, including Wyatt Earp’s Dodge City friend and confidant Bat Masterson (who in his later years was a sportswriter in New York), Charles Dana Gibson, Grantland Rice, Leo Carrillo (the Cisco Kid’s sidekick Pancho), Irvin S. Cobb, and soon-to-be golf partners, author Alfred Damon Runyon (Guys and Dolls) and baseball legend Babe Ruth. In 1916 he introduced his young unknown partner and protégé Norman Rockwell—with whom he shared a studio in New Rochelle, New York that once had been owned by famous western artist Frederick Remington—to the Saturday Evening Post, thus initiating a relationship that lasted more than 50 years. In May 1916, at the insistence of Forsythe, Rockwell published his first Saturday Evening Post cover illustration, of children. Rockwell would later paint a portrait of Forsythe and brand him one of the finest illustrative painters in the United States.

In 1920, homesick, “fed up with the snow and ice” and wishing to concentrate on his Western and desert paintings (“…to be a real painter of the desert” and not just an “illustrator”), he and his wife ![Forsythe's Alhambra studio became a focal point for artists like Nicolai Fechin (pictured) and Tex Wheeler. In the image, Forsythe stands behind Fechin holding a camera. [© Lee A. Silva collection.]](https://www.historynet.com/wp-content/uploads/image/2013/WW/OCT/fechinstudio.jpg) Cotta left their flourishing New York life and returned to California to start anew, following his good friends James Swinnerton (who had moved West in 1906 with the assistance of Hearst for health reasons) and Maynard Dixon (who left in 1912 for reasons of overwork, stress, artistic license, and sanity). They purchased a home in Alhambra and a cabin in the hilltop town of Fawnskin in San Bernardino County and opened studios in both locations. He would spend his summers in the Fawnskin studio above Big Bear Lake; an area that contrasted sharply with the desert scenes he so loved to paint. Renowned western painter and illustrator Frank Tenney Johnson, whose work appeared in Zane Grey novels, Harpers Monthly, and Field and Stream, soon followed Forsythe’s lead and moved to California where they shared the studio in Alhambra. In 1928 they founded the Biltmore Art Gallery/”Salon” which took up the entire mezzanine floor in the new (1923) Biltmore Hotel on Pershing Square in downtown Los Angeles. It became a hangout and meeting place and they were often joined there by Maynard Dixon, Jimmy Swinnerton, actor and California native Leo Carrillo, and many other celebrities and up-and-coming artists of their day including Nicolai Fechin, Gary Cooper, Norman Rockwell, Ed Borein, and Dean Cornwell (the “Dean of Illustrators”).

Cotta left their flourishing New York life and returned to California to start anew, following his good friends James Swinnerton (who had moved West in 1906 with the assistance of Hearst for health reasons) and Maynard Dixon (who left in 1912 for reasons of overwork, stress, artistic license, and sanity). They purchased a home in Alhambra and a cabin in the hilltop town of Fawnskin in San Bernardino County and opened studios in both locations. He would spend his summers in the Fawnskin studio above Big Bear Lake; an area that contrasted sharply with the desert scenes he so loved to paint. Renowned western painter and illustrator Frank Tenney Johnson, whose work appeared in Zane Grey novels, Harpers Monthly, and Field and Stream, soon followed Forsythe’s lead and moved to California where they shared the studio in Alhambra. In 1928 they founded the Biltmore Art Gallery/”Salon” which took up the entire mezzanine floor in the new (1923) Biltmore Hotel on Pershing Square in downtown Los Angeles. It became a hangout and meeting place and they were often joined there by Maynard Dixon, Jimmy Swinnerton, actor and California native Leo Carrillo, and many other celebrities and up-and-coming artists of their day including Nicolai Fechin, Gary Cooper, Norman Rockwell, Ed Borein, and Dean Cornwell (the “Dean of Illustrators”).

Other artists and celebrities soon followed Forsythe and Johnson to Alhambra and bought homes nearby on Champion Place, forming an artist colony in what has become known as “Artist’s Alley” or “Little Bohemia,” less than 10 miles east of downtown Los Angeles. Horse sculptor Tex Wheeler crafted his renowned life-size Santa Anita Park “Seabiscuit” statue at the Alhambra studio. Rockwell would frequently visit from New York and in later years married Mary Rhodes Barstow, a Stanford University graduate and young neighbor girl to whom Forsythe introduced him. Norman and Mary spent a good part of each year visiting from New York and living with her family in their home at 125 Champion Place; they had married there in the garden on April 17, 1930, and Forsythe was the best man. Rockwell became very active in the community, often using local residents in his paintings, and in fact, one of his most well-known and endearing Saturday Evening Post cover illustrations, the Doctor and the Doll (March 9, 1929), featured Artist’s Alley Champion Place resident and renowned sculptor (and Frank Tenney Johnson’s next door neighbor) Eli Harvey appearing as the doctor and a local neighbor girl as the doll’s “mother.” This painting depicts a child with a somewhat concerned look on her face as she holds her doll up to her physician (Harvey) as he is about to place his stethoscope on the doll’s chest.

Forsythe and Frank Tenney Johnson both joined and became active members of the Rancheros Vistadores (“visiting ranchers”) social club, which was created in no small part by their good friend and fellow artist Ed Borein (friend of Theodore Roosevelt, Jack London, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, Annie Oakley, who was married at El Alisal, the celebrated rock home of Charles Fletcher Lummis, as was Maynard Dixon). They often camped with their close companion and fellow artist, Walt Disney, as well as author and Los Angeles Times columnist, feature writer, and editor Edward Maddin Ainsworth. In later years, Forsythe and his wife Cotta were given a personal tour of Disneyland by Walt before the park was open to the public. Johnson tragically died on New Years Day 1939 (the day after his 42nd wedding anniversary) of meningitis he contracted from a close friend who died from the same a few days earlier.

In 1937, by popular demand, and the fact that he put food on the table, Forsythe revisited Joe Jinks for one more year before quitting his cartoon strips (until 1945’s Greasewood Gus). A national ![]()

![In this rare image, Forsythe (left) and his wife, Cotta, along with good friend Ed Ainsworth (far right), tour Disneyland with Walt Disney prior to its opening in 1955. [David D. de Haas, M.D. collection]](http://www.historynet.com/wp-content/uploads/image/2013/WW/OCT/De%20Hass%20Stitched_002B.jpg) United Feature Syndicate ad campaign promoting the return of Joe Jinks features Forsythe (under the pseudonym “Vic” he used in his cartoon strips) sitting next to his cartoon character Joe in an automobile while driving. Their exchange is typical of Forsythe’s humor and compassion—Vic begins the chat exclaiming “Joe ol’ boy, I want to say you’ve been a mighty good friend to me all these years. You’ve always kept me a leap ahead of the landlord. If it hadn’t been for you I might be swinging a pick and shovel!” Joe replies, “Listen Vic; that’s because you’ve been good to me! You’ve treated me like a human being. You’ve never bounced bricks and rolling pins off my head and I appreciate that. It’s 50-50 ol’ man!!” The ad continues: “Joe and Vic have been separated for awhile, but now they are back together again.… your smiles when you see what Vic makes Joe do from now on are going to be bigger still.”

United Feature Syndicate ad campaign promoting the return of Joe Jinks features Forsythe (under the pseudonym “Vic” he used in his cartoon strips) sitting next to his cartoon character Joe in an automobile while driving. Their exchange is typical of Forsythe’s humor and compassion—Vic begins the chat exclaiming “Joe ol’ boy, I want to say you’ve been a mighty good friend to me all these years. You’ve always kept me a leap ahead of the landlord. If it hadn’t been for you I might be swinging a pick and shovel!” Joe replies, “Listen Vic; that’s because you’ve been good to me! You’ve treated me like a human being. You’ve never bounced bricks and rolling pins off my head and I appreciate that. It’s 50-50 ol’ man!!” The ad continues: “Joe and Vic have been separated for awhile, but now they are back together again.… your smiles when you see what Vic makes Joe do from now on are going to be bigger still.”

In 1949 Ainsworth and Forsythe led famed Texan writer J. Frank Dobie, a friend Ainsworth had met through his membership in the Los Angeles Corral of the Westerners, on an expedition through Southern California from the Huntington Library in San Marino where he was doing research for his book The Mustangs. It seems although Dobie was writing his book on the mustangs, he could not find a “real” one anywhere in Texas. After a meticulous search of the ranches in Southern California, the group finally found what they were looking for on the Rancho Santa Margarita in an area that is now the Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, and Dobie was able to complete and publish his book in 1952.

John W. Hilton (a desert painter in Twentynine Palms, Calif., who was known as “The Man Who Captured Sunshine” and knew such luminaries as Zane Grey, Howard Hughes, “Death Valley” Scotty, James Cagney and President Dwight Eisenhower) had as a child read many of the boy’s magazines illustrated by Forsythe. He grew to admire the artist, little imagining that they would someday meet and Forsythe would become a mentor. Hilton was also a friend of General George S. Patton, whom, in the early 1940s during World War II, he assisted in identifying stateside desert training sites for the North Africa campaign, such as Camp Young (near Mecca and southeast of Indio, Calif.). Patton also had Hilton regularly lecture troops on the hazards of the desert, especially dehydration.

Hilton said of Forsythe’s technique that he had “… a theory he called ‘dynamic symmetry’ ” in which “he would use a series of carefully calculated triangles (and other geometric shapes) drawn in charcoal, and before he started to paint, his canvas would look like a modern impressionistic drawing.” Considered by many an innovative genius, Forsythe also developed an analogy between the tone values in color and the musical scale, “a tone scale used for each of three colors or more used in a painting”—a theme his artist friend Ted DeGrazia would later expand upon in his years of study at the University of Arizona in Tucson. A contemporary critic noted that Forsythe found ways to “organize and simplify all forms and details in his paintings so that the essential message and spirit speak clearly to the beholder.” His color-tones were said to give his paintings “a pure, lyrical singing quality.” He was also hailed for his compassionate approach to Western heritage and his use of humor in many of his canvases. Unlike Forsythe, Hilton (and Swinnerton and Dixon before him) did not like to include people and animals in his desert paintings, as he felt they distracted the audience from the beauty and allure of the scenery, the emptiness and, as one critic termed it, the “loneliness, solitude and quiet peacefulness that goes with it.” Hilton’s premise was he could not improve upon the magnificence nature had already provided.

Forsythe and Hilton were the best of friends and in the early 1940s made a significant contribution to the defeat of the Japanese and Germans and Allied victory in World War II. Hilton, with his expertise in geology and knowledge of the Southern California deserts, was recruited by the United States military for a top secret project involving calcite mines he had discovered below sea level in the Coachella Valley near the Salton Sea, which lies directly on the ominous San Andreas Fault. This area known as the “Borrego Badlands” comprises some of the most rugged terrain in the California desert. When General Patton heard of this development he released Hilton from his duties so he could concentrate fully on this project. The armed forces had developed a use for calcite crystals, a very pure form of calcium carbonate (or limestone), in bomb and anti-aircraft weapon sites, but the mineral, mined under U.S. Marine armed guard, first had to be painstakingly examined for microscopic fractures to find the high-grade specimens required for gunsights. Forsythe assisted Hilton by developing a calcite testing device that greatly expedited the cumbersome process, getting the high-grade optical calcite into the U.S military arsenal much more rapidly and in greater quantity than previously possible. These calcite sights were said to have played a key role in turning the war in the Allies’ favor.

Forsythe, recognized with good friends James Swinnerton and Maynard Dixon as one of the original painters of the desert, once said: “To those who do not know it, the desert may mean a land of drab and barren waste; to those who have walked alone in its silence, it is a land of opal beauty, infinite peace and grandeur and of abundant life…. We were kind of Pioneers, nobody thought the California desert as worth much of anything…they never thought of the desert as a place of beauty.” His paintings did much to change that perception. As one critic put it: “[Forsythe] he manages to infuse that subtle something which speaks life and purposeful activity, warmth, and invitation. The wealth of sunshine and floral beauty is recognized…. Towering mountains…are made to blend with sand dunes.” To thoroughly portray his subject, Forsythe actually lived in the deserts and ghost towns that others feared for the persistent heat, insects, reptiles, lack of water and isolation, and he camped with and interviewed prospectors. He was mesmerized by the desert and by the wildlife and characters that inhabited it. The camping trips Clyde made with his wife, Cotta, not only provided the surroundings for his paintings but also allowed him to gain knowledge of “the lessons the desert has for all who are willing to learn.” He became known for his “Forsythe” prospectors, clouds, burros, and sky. In a somewhat humorous and interesting sidelight, in Forsythe’s own personal copy of the February 1952 issue of Arizona Highways Magazine, now in my private collection, appears an article about his good friend, artist Nicolai Fechin, written by author Frank Waters, who in the future would publish his own book about the Earp brothers and Tombstone. Circled and handwritten in ink in the margin next to a sentence discussing Fechin’s originality in his use of “half-wild burros” in his desert paintings—is the following: [Hey!] “What (a)bout me?” and signed “VCF.”

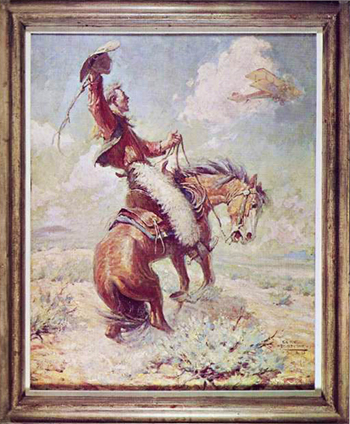

His renowned “Gold Strike” series began as just a single painting born out of a chance meeting with a prospector (“desert rat”) in the deserts of Nevada while on a scouting trip for landscapes to paint  in February of 1926. This series of four paintings was subsequently featured on the cover of Desert Magazine from June through September 1960. John Hilton later said of the series: “These will live in the annals of American art long after the richest gold mines have played out…. [Forsythe’s] paintings of the desert partake alike of the spirit of the Old West and that of modern times.” Nowhere is this better illustrated than in his famous painting, Flying High, where an isolated cowboy riding in a lonely barren desert is seen pulling his horse to a sudden stop and up onto its two hind legs after he looks skyward and unexpectedly spies a biplane flying across their path. He raises his hat high in the air in salute, and yields to the aircraft, knowing he can do nothing to impede progress and the future.

in February of 1926. This series of four paintings was subsequently featured on the cover of Desert Magazine from June through September 1960. John Hilton later said of the series: “These will live in the annals of American art long after the richest gold mines have played out…. [Forsythe’s] paintings of the desert partake alike of the spirit of the Old West and that of modern times.” Nowhere is this better illustrated than in his famous painting, Flying High, where an isolated cowboy riding in a lonely barren desert is seen pulling his horse to a sudden stop and up onto its two hind legs after he looks skyward and unexpectedly spies a biplane flying across their path. He raises his hat high in the air in salute, and yields to the aircraft, knowing he can do nothing to impede progress and the future.

Though best known for his stark desert scenes, Forsythe also painted portraits of many close friends, including Gary Cooper (owned by the Bowers Museum, in Santa Anna, Calif.) and Nicolai Fechin. Forsythe rendered a painting of Will Rogers sitting astride his horse Soapsuds while chatting with cattle king Eddie Vail, as well as another portrait of Rogers, displayed in the 1940 San Francisco Fair and later used to help illustrate wife Betty’s posthumous biography of Will in the Saturday Evening Post. A group photograph adorning the dust jacket of Ed Ainsworth’s outstanding book The Cowboy in Art features Forsythe himself, Norman Rockwell, Roger Jessup, Leo Carrillo and Ed Ainsworth “standing together [in front of Forsythe’s Will Rogers/Eddie Vail painting] at an art show…all members of the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Museum.”

Forsythe was also known to lend a hand and advice to young artists in need, and befriended, among many others, up-and-coming painters Bill Bender (friend of Roy Rogers, Will James, and Cal and Joie Godshall, with whom James lived in his later years), Olaf Wieghorst (friend of Gene Autry, J.P. Morgan, John Wayne, Howard Hawks, and President Eisenhower), Ettore “Ted” DeGrazia (said to be “the world’s most reproduced artist”), and Joe Beeler (founding member of the “Cowboy Artists of America”); four painters who were destined to leave their marks on the world of fine art. Mr. Bender is still alive and active in his mid–90s today. He has lived on the same ranch in a southern California desert community for well over 60 years. Its upkeep takes up most of his day, but he still finds time for his artwork and desert painting. He is a very fine and gracious gentleman and in a recent conversation we had, he still harbored deep and fond memories of “Clyde”/”Vic,” which is how he referred to him at various times in their 20-year friendship. He still has Forsythe’s painting easel, which Vic gave him just before his death. Forsythe also wanted to give his Cadillac and a fine camera to Mr. Bender, but Bill preferred he give these to Cotta Forsythe’s nephew (Thomas Gay of Encino, California) as he was the only living relative they had. In later years, a good friend of the Forsythe’s, Bender, Will James, and many of the early Hollywood crowd and desert artists, the beautiful rodeo stunt rider Jeanne Godshall (daughter of Cal and Joie Godshall) of Victorville, California had a devastating car accident on a freeway off ramp in Studio City, California and Bill and his wife Helen helped to care for her until her premature death.

Victor Clyde Forsythe’s charm and quick sarcastic wit always entertained his friends and family and it was said by those good friends, such as Ed Ainsworth who knew him best, he was “the kindest and most helpful of men” who had “a warm and sympathetic nature” and whose “pervading humor” would “flash forth with devastating suddenness after periods of stoical silence…. Down underneath he is an old softie who will do anything helpful for anybody…. I never knew anyone who quietly helped so many people.” At the San Gabriel Country Club, he was said to be “in constant demand as a golfing partner” as the other members all enjoyed hearing his western anecdotes so much. In a newspaper article celebrating Clyde and Cotta’s 50th wedding anniversary, in the Los Angeles Times on June 13, 1956, the two were touted as a “Golden Rule Couple” and Vic was noted to be the “celebrated cartoonist and western painter whose helping hand for artists, actors, ballplayers, prize fighters, and just plain people has been noted for half a century.” Forsythe refused to take credit for this, but instead chose to thank those who helped him succeed early on in his own career.

In his final years, Forsythe worked out of a studio he maintained above his garage in his home in the small affluent city of San Marino in Los Angeles County, California just north of Alhambra. By the time he died at age 76 at Huntington Memorial Hospital in Pasadena, California on May 24, 1962, “Vic” had traveled the country extensively and had known and befriended the most prominent individuals of his era. He had drawn, painted, and innovated not only with his style and subjects chosen, but also with his method and color tones. He had helped start many a young artist, such as close friend Norman Rockwell, on their path to distinction and fame. He had touched many lives, not the least of which was his beloved Cotta whom he preceded in death by 10 years. His friends and acquaintances had nothing but the highest of praise for not only his talent, but much more importantly his qualities as a human being.

A year after Forsythe’s death the Children’s Hospital of Orange County put on an art show/fund-raiser in his honor, with friend Ed Ainsworth serving as the master of ceremonies. Three of the young artists Forsythe had inspired—Olaf Wieghorst, Bill Bender and John Hilton—made an appearance and displayed their work. Profits from the event went toward construction of the hospital, which thrives to this day. One of only three hospitals that serve children in Southern California’s large and flourishing Orange County, it stands only a few miles from where Forsythe was born 78 years earlier. Although he had his ups and downs, as we all do in life, from the viewpoint of an admirer, his was truly a wonderful life.

Author David D. de Haas, M.D. would like to thank Wyatt Earp biographer and Wild West columnist Lee Silva and author/Curator Emeritus of the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, Don Chaput, for reviewing this article and their suggestions for its improvement, and most importantly for their friendship. He would also like to thank wife Mary for her review and critique of the manuscript and her patience and constant support during his Western field trips and the research, reading and writing process. For further reading de Haas suggests the collected writings of Edward and Katherine Ainsworth, especially The Cowboy in Art (with a foreword by John Wayne). De Haas dedicates this article to author and historian Mark Dworkin, a good friend who died of cancer on August 31, 2012, having just completed his book, American Mythmaker: Walter Noble Burns and the Legends of Billy the Kid, Wyatt Earp and Joaquín Murietta.