When Raeburn Van Buren was a struggling magazine illustrator hoping to break into the big time, he grudgingly enlisted in the Seventh New York National Guard Regiment in 1917. Although he preferred the bohemian life of a New York City artist to the unsure future of a doughboy, it was the right thing to do with the United States at war with Germany. And as it later turned out, it was also a good career move.

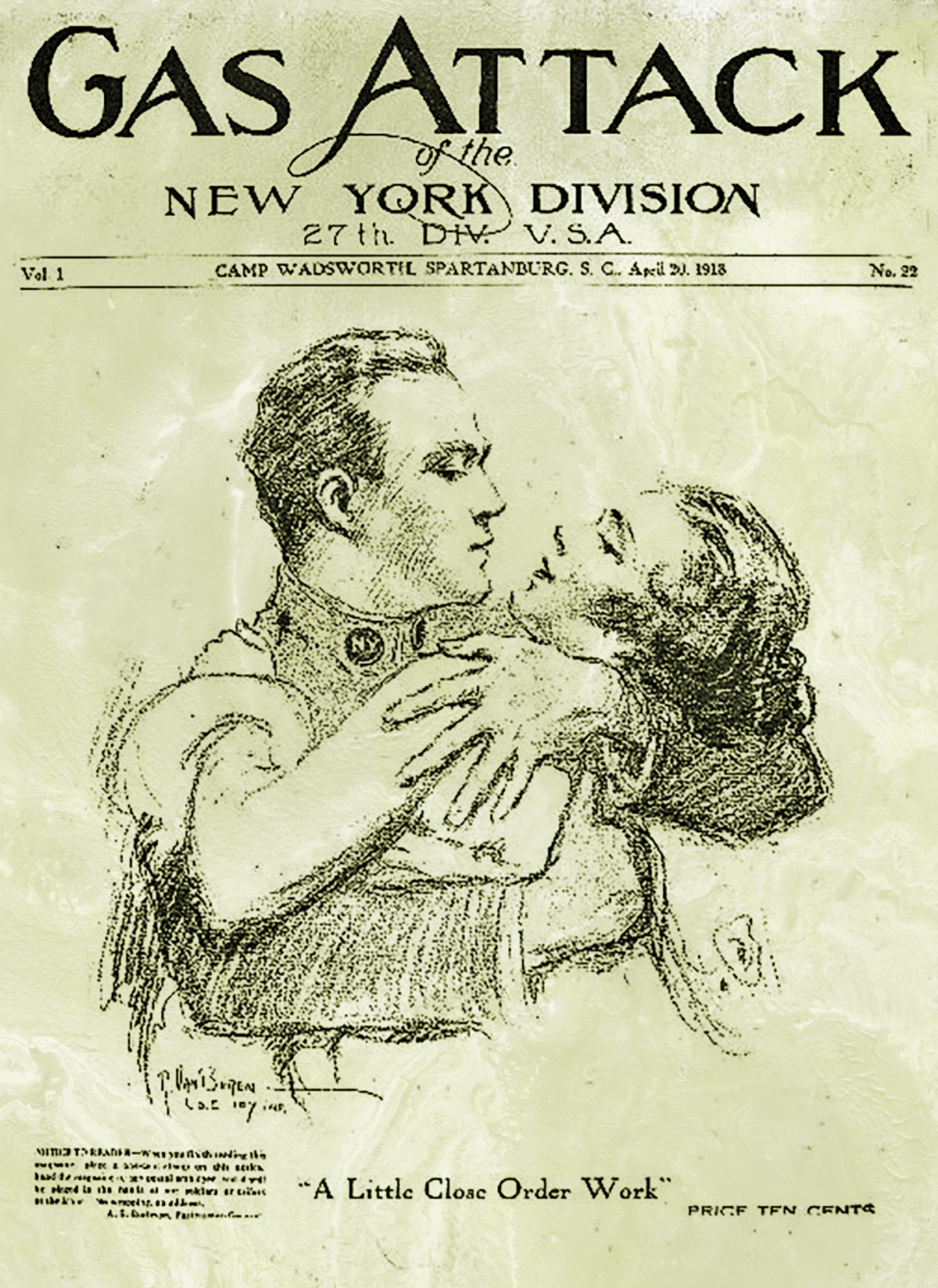

Soon after the Seventh merged with the First Regiment from upstate New York to become the 107th Infantry Regiment, Van Buren, then 25 years old, found himself art editor of The Gas Attack, the spirited and well-read magazine of the Twenty-seventh Division. It was a dream assignment for the young illustrator. It allowed him to show off his talent and humor to nearly 30,000 men, to keep their spirits up, and to gain more recognition back in Manhattan, where most of the country’s major news papers and magazines were headquartered and where copies of each issue of The Gas Attack were sent.

In a letter from France he proclaimed to his mother: “I want to do all I can to keep these fellows over here cheerful.” Van Buren succeeded. By war’s end the New York Times compared his sketches of the war with those of the famous British war cartoonist Bruce Bairnsfather and dubbed him “an American Bairnsfather.” His work in The Gas Attack brought him the fame he sought, and he had hardly shed his lice infested uniform when, in the spring of 1919, he hit the big time–selling sketches to Collier’s and McCall’s and then The Saturday Evening Post, and later to an upstart publication called The New Yorker. His success in magazine illustration then led to his collaboration with cartoonist Al Capp of ” Lil’ Abner” fame to create the comic strip “Abbie an’ Slats.”

A slight redhead with a face filled with freckles, Van Buren was a born comic who loved one-line gags. He sprinkled his conversation with those quick jokes and used one quip after another to make his letters from France hilarious accounts of the day to-day hardships of soldiering. In one letter to his mother, for example, he com plained about the mud and how long he had been wearing his uniform: “We only take them off when we have a bath and baths are as hard to find around here as hair pins and lace.” He was at his best when he illustrated those one-liners with drawings that were a cross between realism and what cartoonists describe as the “big-foot” style (the emphasis on exaggeration), or “ink and paint twisting,” as Van Buren once defined it. Yet, there was one other talent that put him a notch above many of the illustrators of the day: his exceptional ability to draw beautiful women.

Van, as he was called by his friends, had lived in New York City for only four years when the United States declared war on Germany. He arrived from Kansas City after a stint as a sketch artist on that city’s great newspaper, the Star. In those days, the Star was a wonderful training ground for writers and illustrators. Among its alumni were Ernest Hemingway, Russel Crouse, and Eugene Pulliam, the grand father of former Vice President Dan Quayle. Van Buren covered murders, robberies, and petty crime, much like the way a photographer does today, only instead of a camera he used a sketchpad and pencil. After selling a few gag drawings to the humor magazines Judge and Puck, he headed off to New York, a time-honored journey almost as old as Gotham it self-young artist, big dreams, big city.

Van Buren did not come alone. With him were three other young Missourians with the same big dreams: artist Thomas Hart Benton, caricaturist Ralph Barton, and actor William Powell. They shared a studio apartment in the Lincoln Arcade near the site of today’s Lincoln Center the “new Bohemia,” the Times called the neighborhood. At night, rats rattled around in the ceiling.

The other tenants were, according to Van Buren, “old ladies and their pet parrots,” except on the floor above them, where another struggling artist lived. She was illustrator Neysa McMein, a “tall, lithe beauty,” penned her biographer, with a “softness in her manner and calmness in her person which many men found very reassuring.” Van was smitten by her. Whenver McMein wanted him to visit she stamped her foot on the floor, and he eagerly sneaked up the fire escape. She loved to play poker with the boys, and in her apartment Van met the leading wits of New York: Franklin Pierce Adams, Heywood Broun, Alexander Woollcott, and others. It was no wonder that in the summer of 1917 he only grudgingly gave up this exciting bohemian lifestyle for that of a soldier.

The Seventh was one of the oldest National Guard units in the United States, with a history dating back to 1806. Its armory still stands on Park Avenue in Manhattan’s posh Upper East Side, an area known as the Silk Stocking District. The officers and men of the Seventh were for the most part sons of New York society. Their names were a who’s who of the rich and famous–Belmont, Harriman, Rhinelander, Roosevelt, Vanderbilt, Van Rensselaer, and, with the youngster from Kansas City joining up in 1917. In fact, he traced his lineage back to President Martin Van Buren. In the 1870s, the Seventh had privately raised money from these same families to design and build its mammoth armory. The land it was built on was donated by the city.

Also in the 1870s the Seventh established a remarkable magazine called The Seventh Regiment Gazette. It was the forerunner of the Twenty-seventh Division’s own publication, The Gas Attack. The Gazette was edited by some of the best newspapers and magazine editors in the city who were members of the regiment. Needless to say, it was well written and well illustrated. One of its art editors was Gordon Grant, among America’s best illustrators and whose powerful painting of the frigate Constitution was used by the Navy Department to raise money to save “Old Ironsides.” Today that painting hangs in the White House.

When the editors found out that Van Buren had enlisted in their regiment they pestered him for gag drawings. He responded with a centerfold of a soldier sunk down in a huge, soft bed. Smoke rings curl above his head. A beautiful, dark-haired girl is entering the room with a tray of steaming food. The caption reads: “And then the bugle sounded!”

That sketch and several others grabbed the attention of the staff of The Gas Attack, except then it was titled Wadsworth Gas Attack and the Rio Grande Rattler. At the time, the Twenty-seventh Division was training at Camp Wadsworth in Spartan burg, South Carolina. The origin of its magazine dated back one year to 1916, when the New York National Guard had been called up for duty along the Mexican border to protect Texans while General John Pershing led a punitive expedition across the Rio Grande against the revolutionary warlord Pancho Villa. Major General John F. O’Ryan, division commander, authorized the magazine’s start-up. It was called The Rio Grande Rattler. The first managing editor was Major Franklin W. Ward, who later had command of the 106th Infantry. The assistant editor was Captain Wade Hampton Hayes of the Seventh Regiment, former Sunday editor of the New York Tribune.

Then the division went to South Carolina in the fall of 1917, the magazine’s title was changed to the unwieldy moniker of Wadsworth Gas Attack and the Rio Grande Rattler. Soon after, it became just The Gas Attack. In the early spring of 1918, Van Buren was asked to be its art editor. He in formed his mother that it was a thank-you job. “But it will get me out of drill about two afternoons a week and I will have a nice little office to work in over the Y.M.C .A. building.” He also wrote: “I believe [camp life] is helping my artistic eye. Since I have been here I have made quite a few sketches and they have showed marks of real art. I seem to be able to see better.” While the regiment was at Camp Wadsworth, the War Department merged it with the First Regiment and gave it a new numerical designation, the 107th Infantry. Colonel Willard Fisk, a Seventh veteran of 44 years, was named commander. He assembled all his troops and assured them, “We are still the First and the Seventh, but with Nothing in between!”

The newly named 107th Infantry Regiment, along with most of the Twenty-seventh Division, steamed into Brest, France, at the end of May 1918. The division eventually became part of the American Second Corps. For training purposes it was attached to the British Third Army and then in early July to the British Second Army in Flanders. Here in the shadow of Mont Kemme and along the shores of the fetid Dickebusch Lake in a sector called the East Poperinghe Line, or “East Pop,” the regiment experienced trench warfare for the first time. Each company was taken up to the front lines for a stay of eight days. Van Buren was in E Company, and when the time came for the unit to move up for a turn in the trenches, a dozen or so New Yorkers had already been killed in combat. The company hunkered down near Dickebusch Lake. Van Buren found a dugout home near the lake, shored up by thick timbers. For the next eight days he stayed there. With not much to do except keep his head down, he found a shard of glass and, using it like a pencil, drew, or rather carved out, a drawing of a beautiful woman on one of the timbers. When he had finished, the woman brought cheer to the men of E Company.

In the meantime, O’Ryan had a visitor. The famous portrait painter John Singer Sargent had been commissioned by British Prime Minister Lloyd George to paint English and American troops fighting side-by side. The story of Van Buren’s woman reached O’Ryan’s headquarters while Sargent was busy sketching the general’s portrait. When he heard about it, the famous painter wanted to trek to the front to see this work of soldier art. O’Ryan advised him against it, but Sargent went anyway. He was accompanied by three officers, including an aide to O’Ryan, Captain Tristram Tupper, who later wrote about it for the Times. Sargent’s trip to the trenches took two hours. According to Tupper it was an “evil night to look for a dugout where a young soldier artist by the name of Van Buren had drawn on the wall… a remarkable picture of a woman.” Tupper painted a vivid word picture himself, of “big throated guns” and “their fiery tongues and the whistle of the shells as they spat toward the enemy.” He reported how the ground smelled of toxic gases and that Dickebusch Lake was nothing but a stinking marsh filled with poisonous pools of water. He thought “it ‘s a strange place for a young artist to have dreamed of a woman and stranger still that he should have transcribed his dream from his mind to the rough wall.” Once inside Van Buren’s dugout home, Tupper noticed that the “senses are distinctly affected by three things, first, the decreasing sound of the artillery fire, next, the seeming thickness of the darkness and, finally, the strange odors of the earth.”

Sargent was appalled. “There ‘s nothing here!” he said. “There’s nothing here! No artist ever worked in a place beneath the ground like this!”

Then they lit a candle, and it’s glimmer of its light Sargent looked at Van Buren’s sensuous work of art. “On the wall,” wrote Tupper, “a woman had been drawn with seeming carelessness–a creation of the war.” It was suggested that they cut out the timber and bring the carving back for safekeeping. “This is the only frame that suits it,” Sargent said. “It should be left here.” And it was, said Tupper, “the woman of the war.”

After E Company’s eight-day stint in the trenches, Van Buren was reassigned to divisional headquarters to help put together a history of the Twenty-seventh in the Great War. His new job kept him out of the attack on the center of the Hindenburg Line that began on September 29. The men of the 107th Infantry led the charge, opening the way for the Australians to leapfrog them and drive the Germans out of their vast stronghold. The New Yorkers lost heavily that day, suffering more than 60 percent casualties. They also earned four Medals of Honor, the most by a regiment for a single day’s action in the war.

There was little respite for the division. In one engagement after another, it drove the Germans back toward the Rhine River. Van Buren reflected in a letter home, “We keep moving East every other day, and the further we go the deeper we get into the darkness of this dream.”

After the Battle of the Selle River, the division was pulled from the line for the last time. It was late October, and the writers and artists began work on the next issue of The Gas Attack. Tupper served as editor; Leslie Rowland of the 107th, a Broadway newsman in his civilian days, was the man aging editor; and Van Buren, of course, continued his role as art editor. If ever the boys needed cheering up, now was the time.

“I am working hard to make my end of it as good as possible,” he boasted to his parents. “I have already turned out four large drawings and the ‘rise’ they got from the few who have seen them encourages me to do more.” He discovered that his work seemingly had matured, and he let his parents know that as well: “I seem to get into every picture I do and it shows up in the finished product.”

The New York press seemed to agree, too. Gotham’s newspapers, from the Times to the Herald to the Sun, commented on the Christmas issue of The Gas Attack when it reached the city in January 1919, two months after the war had ended and two months before the Twenty-seventh Division arrived home. The Times reproduced two cartoons by Van Buren. In an accompanying article, it reported:

One of the discoveries of The Gas Attack in France is an American Bairnsfather in Private Raeburn L. Van Buren. His drawings carry the New York soldiers from their landing in Brest through the months of fighting with the British and Australians to the last days before the armistice, when the soldiers were beginning to think more and more of Christmas and home. Most of them are humorous and laughable; in others there is a touch of sympathy, tenderness and sentiment–common feelings among the American soldiers that have made them the most beloved of comrades for all their allies.

Van Buren suddenly had the recognition he had been seeking before the war. Magazines wanted his work. Soon his pen-and-ink illustrations were showing up all over the country. Not only was he busy with work, but he was back in bohemia. Yet it was not the same. Life now felt empty after what he had seen in the war. He moved out of Manhattan for the sedate suburban life in Great Neck. He bought a house, got married, and for the next 60 years or so spent his days hunched over a drawing board. He eventually illustrated more than a thousand stories for all the major magazines and then at age 50, when most people are looking forward to retirement, embarked on a new career: drawing the popular comic strip “Abbie an’ Slats.” When he died in 1987, Van Buren, the American Bairnsfather, was 96 years old.

STEPHEN L. HARRIS is the author of Duty, Honor, Privilege: New York‘s Silk Stocking Regiment and the Breaking of the Hindenburg Line (Brassey’s, 2001). Raeburn Van Buren was his great uncle.