Medal of Honor recipient, then prisoner of war.

In spring 1967, Maj. Leo Keith Thorsness was a 35-year-old pilot in a two-seat F-105F Thunderchief fighter-bomber flying over North Vietnam to locate and destroy sites that launched surface-to-air missiles at America’s big B-52 bombers. The 16-year Air Force veteran, an Eagle Scout from Walnut Grove, Minnesota, had racked up an impressive record. On Dec. 2, 1966, he earned the first of six Distinguished Flying Crosses, followed on Jan. 15, 1967, by the first of two Silver Stars.

Thorsness was flying with three other Thunderchiefs southwest of Hanoi on April 19, 1967, when they detected the radar of a SAM site. Thorsness released a guided missile and destroyed the warhead. Turning toward a second SAM site, he dropped a cluster bomb and descended to 3,000 feet to scour the area for other threats. Groundfire erupted around his F-105.

In the distance Thorsness’ wingman, Maj. Tom Madison, was taking hits from anti-aircraft guns and going down. The parachutes of Madison and his electronic warfare officer, Maj. Tom Sterling, opened in the sky. Thorsness saw a MiG-17 bearing down on the parachuting crew and in an instant was on the enemy craft, destroying it and luring other enemy fighters away from his falling comrades.

Low on fuel, Thorsness left to hook up with a tanker for aerial refueling, while rescue helicopters and their fighter escorts raced to Madison’s position. After the refueling, Thorsness turned his jet back toward the rescue effort and encountered a group of MiGs, outnumbering him 4 to 1. Undaunted, Thorsness went on the offensive, damaging one MiG and drawing the others away from the rescue site.

His ammunition depleted and needing more fuel for the long flight to his home base, Thorsness again headed toward a tanker, but another aircraft was so critically low on fuel that its crewmen would have to bail out unless they got immediate refueling. Thorsness gave them the tanker and set his plane on course to the nearest airfield. He glided in on vapors and prayers.

Sadly, the rescue attempt for Madison and Sterling was unsuccessful. The two American aviators were captured and interned as prisoners of war.

Eleven days later, on his 93rd mission, Thorsness was shot down by a MiG-21. He and his electronic warfare officer, Capt. Harold E. Johnson, parachuted onto enemy soil and were captured. The major’s resistance to his captors during six years as a POW earned him a year in solitary confinement, and severe torture left him with serious, permanent spine damage.

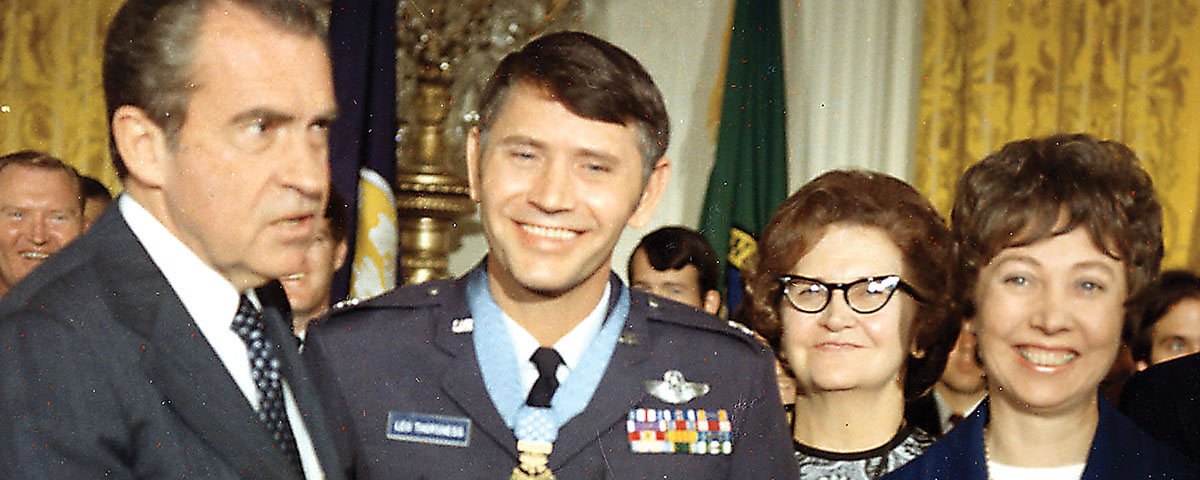

Thorsness learned privately from another prisoner that he was to be awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions on the day Madison and Sterling were downed. The award, however, was not announced for fear that his captors would use it as an excuse for even more brutal treatment. Thorsness was released on March 4, 1973, during Operation Homecoming. Seven months later, President Richard Nixon draped the medal around the Air Force hero’s neck.

In 1974 Thorsness ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Senate in his wife’s home state of South Dakota, and four years later the Republican lost a bid to represent the state’s 1st Congressional District. After moving to Washington state in 1988, Thorsness won an election for state senator. In 1992 he lost in the primary contest for one of the state’s U.S. Senate seats.

Thorsness served as president of the Congressional Medal of Honor Society in 2010-11, representing all living recipients of the medal with quiet dignity. The only American to be held as a POW after earning the Medal of Honor died on May 2, 2017, in Jacksonville, Florida, after retiring in St. Augustine.

Doug Sterner, an Army veteran who served two tours in Vietnam, is curator of the Military Times Hall of Valor, the largest database of U.S. military valor awards.

First published in Vietnam magazine’s February 2018 issue.