Air Force AC-47 gunships, called “Spooky” and “Puff the Magic Dragon,” prowled the skies over South Vietnam during the dangerous hours of darkness when grunts on the ground would come under attack. Their miniguns could rain one 7.62 mm round every square foot at 6,000 rounds per minute on an encroaching enemy. In seconds, Spooky could also chase away the darkness with the intense light from magnesium flares dropped by parachutes.

On the night of Feb. 24, 1969, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army threatened American positions near Saigon in the Long Binh area. Several outposts came under mortar and rocket attack, and enemy soldiers began to probe the tenuous American positions. Throughout the night, the 3rd Special Operations Squadron’s Spooky 71, piloted by Maj. Kenneth Carpenter, was on the scene. Three men fired Spooky’s miniguns, and Airman 1st Class John Lee Levitow dropped flares.

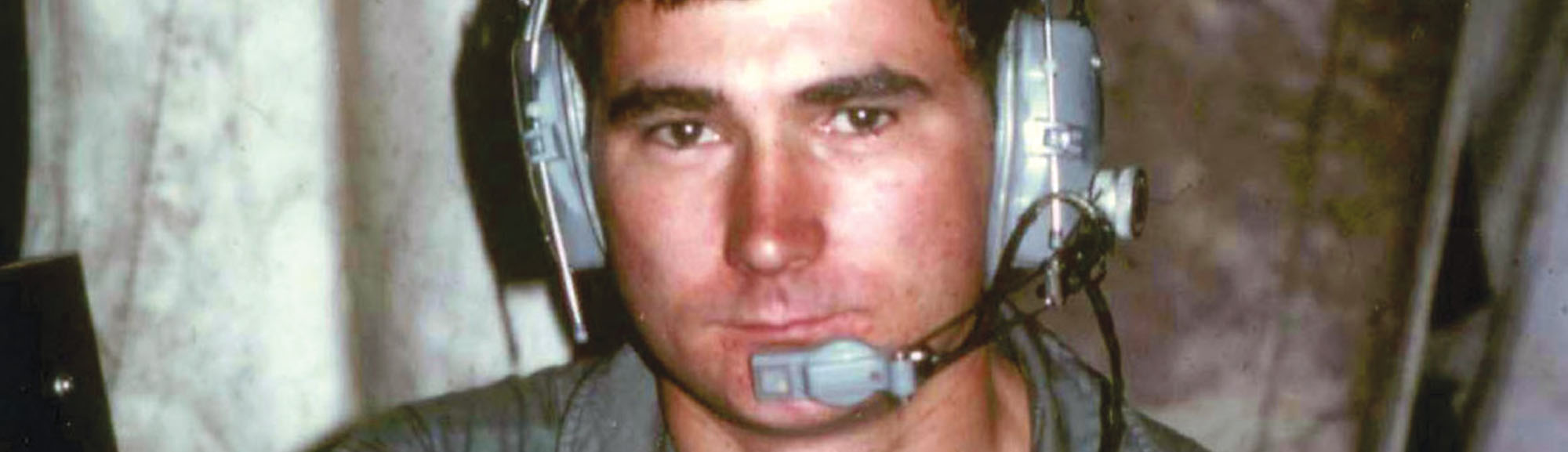

Levitow, who oversaw the plane’s cargo-loading operations, had flown 180 Spooky missions. That night he was replacing Carpenter’s regular loadmaster, who had sat in for Levitow when the 23-year-old from Glastonbury, Connecticut, was ill.

Close to 11 p.m. Carpenter received a call to help Americans being shelled by mortars south of Long Binh. He quickly navigated to their position. In the cargo hold Levitow took a 27-pound flare canister from the rack, set the timers and gave it to Airman 1st Class Ellis Owen, who was about to toss it out the side cargo door when an explosion from an 82 mm mortar round tore a 2-foot hole in the right wing. More than 3,500 pieces of shrapnel pierced the thin skin of the cargo hold, wounding all four men.

Despite the pain of more than 40 wounds and the wild gyrations of the aircraft, Levitow staggered toward the open door where a wounded comrade lay dangerously close to being thrown out of the plane. While dragging the man to safety, he saw smoke from a flare—the one with the timer he had set just seconds earlier. It had been yanked from Owen’s hands by the explosion.

Ignoring his pain, Levitow followed the elusive canister, reaching for it as time after time it rolled beyond his grasp. With only a few seconds left before the flare exploded, he threw himself on the still-smoking, 2-foot long canister and, holding it close to his body, crawled to the door. Bleeding badly, his strength fading, Levitow finally reached the opening and pitched the flare into the sky. Just after the flare left the plane, it exploded.

Despite the heavy damage to Spooky 71, pilot Carpenter was able to make an emergency landing. After a slow recovery, Levitow returned to duty, flying 20 more missions before he returned home and was discharged in the spring of 1970. President Richard Nixon recognized Levitow’s heroism with the Medal of Honor on May 14, 1970.

The Air Force Medal of Honor, created in 1947, has been awarded to 18 men—four in the Korean War and 16 in Vietnam. Levitow was the only enlisted airman to personally receive the award. (Two enlisted airmen from Vietnam who were posthumously awarded the Air Force Cross had their awards upgraded to the Medal of Honor in 2000 and 2010.)

Levitow never saw his unique distinction as a special honor, but rather as an obligation to serve fellow veterans, enlisted airmen in particular. “Because of this,” he told me, pointing to the medal around his neck at a Medal of Honor convention in 1997, “I can never retire.”

He did not, serving in Connecticut’s veterans agency and speaking at Air Force events until his death from cancer in 2000. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

Doug Sterner, an Army veteran who served two tours in Vietnam, is curator of the world’s largest database of U.S. military valor awards.

Published in the October 2017 issue of Vietnam magazine.