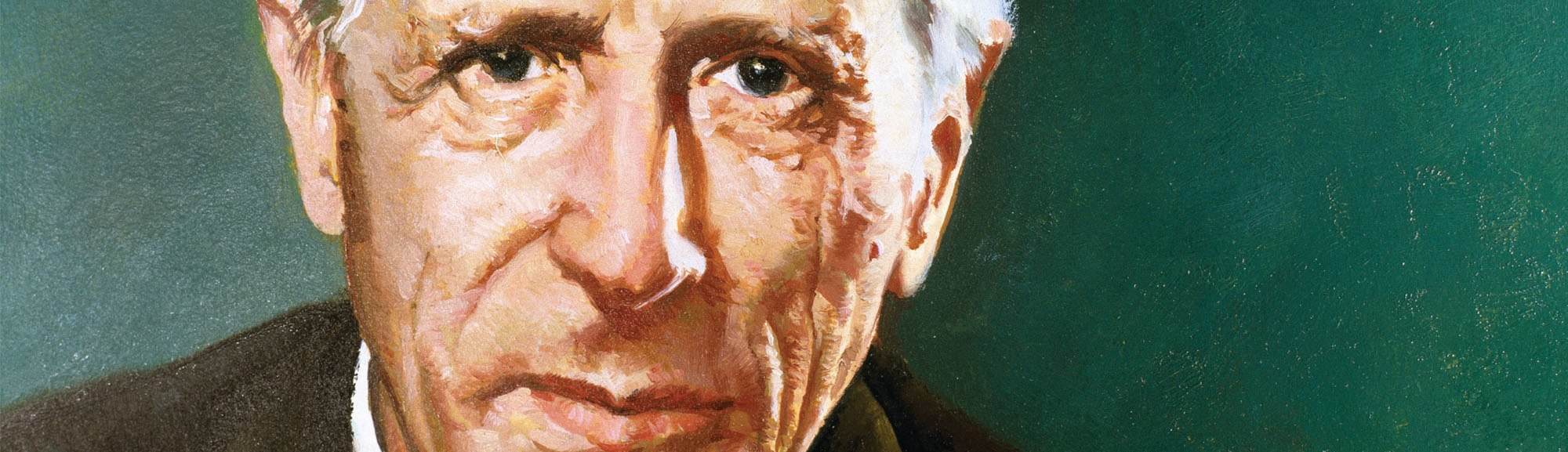

By 1914 Jesuit Father Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was a promising young anthropologist, paleontologist, theologian and philosopher. Yet he served dutifully on the Western Front as a noncombatant French army stretcher-bearer. For his service under fire he received the Légion d’honneur, the Croix de guerre and the Médaille militaire (pictured), his nation’s highest award for combat valor.

By 1914 Jesuit Father Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was a promising young anthropologist, paleontologist, theologian and philosopher. Yet he served dutifully on the Western Front as a noncombatant French army stretcher-bearer. For his service under fire he received the Légion d’honneur, the Croix de guerre and the Médaille militaire (pictured), his nation’s highest award for combat valor.

Born in 1881 at his family estate near Clermont-Ferrand, Teilhard was educated in Jesuit schools in France until 1902, when forced to transfer to England after the French government shut down all parochial schools nationwide. After taking his vows in 1911 in Hastings, he returned to France to pursue a doctorate in geology at the Sorbonne in Paris. But the war interrupted his studies.

Called up in December 1914, Teilhard reached the front in the new year. Serving with the Zouaves for the duration, he witnessed some of the bloodiest battles of the war, at Ypres and Champagne in 1915, Verdun in 1916, along the Aisne in 1917 and on the Marne in 1918.

As happened to many of his fellow soldiers, Teilhard’s frontline service profoundly influenced his worldview, aspects of which clashed with Catholic orthodoxy. “A man who his country has committed to the fire,” he observed mystically in September 1917, “has concrete evidence he no longer lives for himself—that he is freed from himself—that another thing lives in and dominates him.”

Despite his long stint, the highest rank Teilhard achieved was corporal. He turned down assignment as divisional chaplain with the rank of captain, saying simply, “Leave me among the men.” While officially a medic, he remained a priest and continued to perform his religious duties. One officer who served with Teilhard recalled one occasion at the front near Nieuport when Teilhard celebrated an entire Mass hunkered on his knees in a shallow trench.

Many of his fellow Zouaves were Muslim. To establish rapport with them, he abandoned his blue French service uniform and kepi in favor of the khaki uniform and red fez of the African colonial troops. The Muslim soldiers called him le sidi marabout—roughly translated as “the honorable holy man.”

On Jan. 30, 1919, Teilhard crossed the Rhine into Germany with his regiment, and his unit was demobilized that March. He’d lost two brothers to combat.

Following the war, Teilhard achieved renown as an anthropologist and paleontologist, even while stoking controversy with his contrary views on evolution and original sin. In 1925 his own Jesuit order ordered him to repudiate his theories and give up teaching, though he remained a lifelong member of the order. As late as 1962, seven years after his death in New York City, the Vatican cautioned against teaching Teilhard’s published works.

But the disgraced Jesuit and former combat medic has since become something of an intellectual cult figure, and several recent popes, including Benedict XVI—history’s first Jesuit pope—have referenced his works. It was Teilhard’s personal experiences in the blood and mud of the Western Front that proved a decisive influence on his still debated philosophy and beliefs.