The United States Colored Troops present at Appomattox in April 1865 made history on a number of levels. Not only were they part of the black and white forces—a “regular checker-board” in the eyes of one Union staff officer—that brought Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to bay, but they were also a living, breathing example of the social restructuring that the conflict had brought about.

For many years historians estimated there were 2,000 USCTs present at Lee’s surrender, but modern studies have proved that estimate was far too low. In 2013–2014 the Appomattox 1865 Foundation, the friends group for Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, obtained a grant so a researcher could look through the Compiled Military Service Record of each soldier in the nine USCT regiments that participated in the Appomattox Campaign and account for each soldier present in April 1865. The count resulting from that research found that the six USCT regiments on the battlefield the morning of April 9, 1865, numbered between 4,000 and 5,000 men. The regiments were large by 1864 standards. Though they had seen some action, their attrition rate was still low: Each regiment present numbered from 661 to 901 men.

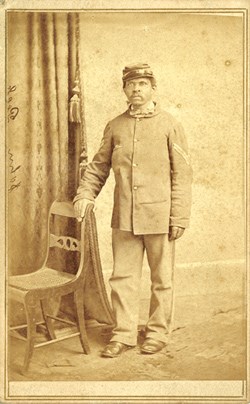

Despite those numbers, no identified wartime photo of a USCT enlisted man who had been present at Appomattox was known of until this last summer, when John Peck’s image appeared in the special issue produced by Civil War Times, 1864: A Year of Relentless War. A quick check of the new list confirmed that Peck had indeed been present at the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, and that at last an image of an Appomattox USCT had surfaced.

The journey that led Peck to be slogging along in the mud toward Appomattox Court House in April 1865 with Company E of the 8th United States Colored Troops began in 1863, when he traded his barber chair for a soldier’s uniform. The native of Meadville, Pa., was 22 years old when he crossed the state to muster in at Camp William Penn in Philadelphia on October 17. His regiment sailed for Hilton Head, S.C., in mid-January 1864 and soon became part of an expedition to Jacksonville, Fla. On February 20, the 8th suffered heavily at the Battle of Olustee, and sustained more than 300 casualties, including 87 killed or mortally wounded. A Rebel trooper struck Peck on the head with a saber late in that engagement, resulting in a 1½-inch scar over his right eye.

The 8th traveled to Virginia in August to become part of the Army of the James, which was soon engaged in action with Confederate forces between Richmond and Petersburg, near Deep Bottom. At the Battle of Fort Harrison on September 29, a bullet struck Peck a glancing blow 5 inches from his eye, leaving a slight depression on the left side of his head. The wound was apparently not severe, however, and Peck received a promotion to sergeant on October 10—despite the fact that he was illiterate.

In January and February 1865, Peck returned home on furlough. When he rejoined his unit, he found there was an entire corps, the XXV, made up of USCTs commanded by Maj. Gen. Godfrey Weitzel.

On April 2, 1865, most of General Weitzel’s men were knocking at Richmond’s gates as Brig. Gen. William Birney’s 2nd Division moved south and west of Petersburg with two divisions of the XXIV Corps under Maj. Gen. John Gibbon and Army of the James commander Maj. Gen. Edward Ord. The 8th was in Colonel Ulysses Doubleday’s 2nd Brigade with the 41st, 45th and 127th USCTs. The 3rd Brigade, under Colonel William W. Woodward, included the 29th and 31st USCTs, and the 1st Brigade’s 7th, 109th and 116th USCTs took orders from Colonel James Shaw Jr.

Those units entered Petersburg at 6 a.m. on April 3. As General Ulysses S. Grant’s troops headed after the Army of Northern Virginia, the Army of the James, including the USCTs, marched to the south of Lee’s army. When the division reached Farmville on April 7, Birney was relieved and assigned to take charge of the Division of Fort Powhatan, City Point and Wilson’s Wharf, and his two regiments were assigned to other divisions in the XXIV Corps.

Army of the James soldiers remained south of Farmville on April 7, blocking Lee from turning south and forcing him to move to the north side of the Appomattox River and head toward Appomattox Station in hopes of securing supplies scheduled to arrive via train from Lynchburg. But the next day about 4 p.m., Union cavalry captured the Confederate supply trains Lee was expecting, along with 25 cannons, and secured a lodgment on the Richmond–Lynchburg Stage Road to block Lee’s line of retreat.

After Lee met with Generals John B. Gordon, James Longstreet and Fitzhugh Lee, he assigned Gordon to break through the Union line. Lee’s nephew, Fitzhugh, commanding the Confederate cavalry, would support Gordon on the right and perform a left wheel to drive off the Federal cavalry, open the road and hold it while the rest of the army availed itself of the opening. But on April 8–9, the hard-marching Army of the James spoiled Lee’s plan.

An exhausted John Peck and the men of the 8th had marched 35 miles in one day, with only three hours’ rest overnight. General Ord rode along the column, telling his men that “legs would win the campaign and end the war”—encouragement that apparently served to buoy their spirits.

About 7:30 a.m. on the 9th, the boom of cannons and crack of rifle fire put an end to a short rest Peck and the others were enjoying. Hard pressed by Confederate infantry and cavalry, the Union cavalry had begun to vacate their defensive position on the ridge just as the Army of the James arrived within supporting distance. Doubleday promptly sent his brigade marching toward the fighting, with Peck and his comrades of the 8th and the 41st forming the first line.

As the retreating Union troopers streamed by to re-form, their commander, Brig. Gen. George Crook, paused to watch the USCTs go into action. He later reported: “We had not proceeded far before we met the…‘Darks’ marching up to the front. I had heard so much pro and con about the fighting qualities of the Negroes that I sent my staff back to reorganize my command while I went along with this corps to see for myself how these people would fight. They were the first I had seen in any numbers….They marched up in splendid order, and although some of them were knocked over, they showed no flinching.”

The USCTs deployed skirmishers and engaged the enemy, with Doubleday’s men repulsing the Confederate advance. To Peck’s right, soldiers in the 41st began falling, including 40-year-old Thomas Crawford, another barber from Meadville, who would lose his right eye after being struck in the head by a bullet. Also wounded that day was 24-year-old Captain John W. Falconer of Company A of the 41st, who crumpled and fell from his horse after a bullet hit him. A Hamilton, Ohio, native who had originally enlisted in the 3rd Ohio Infantry, Falconer died from his wounds two weeks later.

After seeing three regiments of USCTs on the left flank and between two divisions of white troops, a staff officer called out to the retiring cavalry, “Keep up your courage, boys; the infantry is coming right along—in two columns—black and white—side by side….” Woodward’s men advanced at the double quick, with their rifles at “right shoulder shift,” and let the retreating cavalry pass through their ranks.

The troopers were happy to see the USCTs. The 1st Maine Cavalry’s regimental history states, “As the men reached the woods at the edge of the field they met the infantry…black, to be sure, but their uniforms were blue and their hearts loyal, and the men were glad to meet them….” The Maine cavalrymen called out “Bully for you!” as the USCTs advanced.

Woodward’s men paused briefly to drop their knapsacks, then advanced against Gordon’s forces. They had pushed the enemy skirmishers back for nearly a mile when white flags were raised to stop the fighting. Upon the announcement that Lee had formally surrendered, wild celebrations broke out.

Sergeant Major William McCeslin of the 29th USCT wrote: “We, the colored soldiers, have fairly won our rights by loyalty and bravery—shall we obtain them? If they are refused now, we shall demand them.” Thomas Jordan, the 127th’s chaplain, declared, “We are a part of the army to which Gen. Lee, the Generalissimo of the C.S.A., has surrendered and have a share in the glory.”

The XXV Corps returned to Petersburg after leaving Appomattox. In late May its men boarded steamers headed for Texas, to bolster the Federal presence along the Rio Grande as a show of force to the French under Emperor Maximilian in Mexico.

The 8th returned to Philadelphia and mustered out on November 10, 1865. Peck probably returned to Meadville for a time, but he did not remain there, subsequently settling in Paducah, Ky. Despite his injuries and battle scars, he was not considered too disabled to perform manual labor, and his application for a pension was rejected in 1891. The pension review board wrote: “This is a large and powerfully built man—appears to be in perfect health.”

That summary rejection no doubt came as quite a blow late in John Peck’s life. We can only hope the former USCT sergeant derived some satisfaction in knowing that he had helped block Lee’s escape route at Appomattox—and survived to celebrate the South’s surrender. But he could not have known that his trip to a photographer would furnish posterity with the face of one USCT who was there at the end.

Patrick A. Schroeder, historian at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, has written or contributed to more than 20 Civil War books, including Thirty Myths About Lee’s Surrender and More Myths About Lee’s Surrender. This article was originally published in the April 2015 Civil War Times.