The Treasury was on the verge of collapse. Within days, the gold would be gone. The government would be bankrupt.

President Grover Cleveland was getting desperate. The economy had been hemorrhaging jobs since the Panic of 1893; 18 months later, millions of Americans pounded the streets looking for work, huddled around fires in hobo camps against the winter cold, and wondered where they would find food for their crying children. Across the street from the White House, the United States Treasury was on the verge of collapse. Worries among investors that paper dollars would soon be worthless had triggered a run on the Treasury’s gold reserves. Within days, the gold would be gone. The government would be bankrupt. And Cleveland would be blamed.

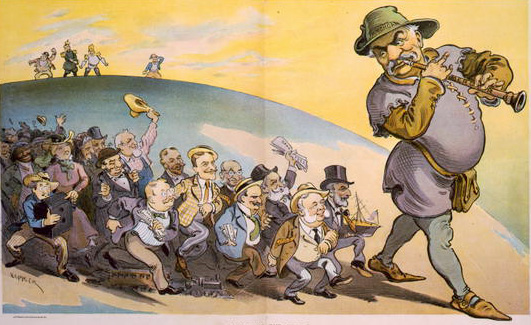

One man could save the day, but Cleveland shuddered at the thought of accepting his help. John Pierpont Morgan was not only the most powerful banker in the country, but also the most despised. His visage alone made babies wail and adults recoil: Chronic rosacea inflamed and deformed his nose, till persons who met him could neither look nor look away. Morgan’s mastery of Wall Street was even more frightening. His command of capital put whole industries in thrall to his whims; ordinary citizens had difficulty believing that anyone so wealthy and powerful could be other than malign. Nonetheless, Morgan’s Midas touch drew Cleveland irresistibly toward him. With the condition of the Treasury growing more dire each day, the president didn’t see how he could avoid making a deal with the financial Gorgon who was the embodiment of the oppressive power of Wall Street.

In the absence of a central banking authority, Morgan was the country’s lender of last resort. Cleveland’s decision to kowtow to him saved the dollar and averted the demise of federal credit. It also provoked an uproar that led to a takeover of Cleveland’s Democrats by the populist wing of the party. Anger toward Morgan was rekindled when he again operated as America’s de facto central banker in the financial panic of 1907, prompting the progressive heirs of the populists to train the withering light of public scrutiny on his practices. Neither Morgan nor his practices survived.

More than a century later, when the subprime mortgage mess plunged America into a deep recession, Washington politicians again felt that they had no choice but to make a deal with the bankers on Wall Street. Only this time, the circumstances were flipped. In Morgan’s day, he put up tens of millions of dollars to save the government and economy. In our day, Washington poured billions into propping up the banks and financial institutions that had brought the economy to its knees. But one thing didn’t change. As the financial panic began to lift, the resentment and hatred of Wall Street was palpable.

“The banker’s calling is hereditary,” Walter Bagehot, the founding editor of London’s Economist weekly, asserted after examining the banking dynasties of Britain. “The credit of the bank descends from father to son; this inherited wealth brings inherited refinement.” J.P. Morgan inherited the banker’s calling from his father and grandfather, who had constructed a financial fiefdom that spanned the Atlantic, with principal offices in New York and London. Morgan apprenticed with a firm associated with his father’s; in the wake of the Panic of 1857 he displayed a boldness that shocked his seniors but earned Morgan a fortune and convinced him he had a gift for the money trade. During the Civil War he speculated in commodities and gold, proceeding from coup to coup until his income reached $50,000 a year, at a time when a skilled laborer might earn $500.

After the war Morgan entered the burgeoning railroad business, underwriting stock issues for the new roads crisscrossing the country. He took a commission on the transactions but also something more: In partial payment he insisted on seats on the boards of directors of the roads. At a time when corporate information was considered proprietary and was commonly withheld even from shareholders, Morgan’s inside position gave him a vantage available to few others. He quickly became the country’s expert on railroads.

He turned the information to good use. Morgan, like many other successful men, perceived a consonance between his personal interests and those of the larger community. Morgan believed he could make money reorganizing the nation’s railroads, but he believed as well that the nation would benefit. Duplication entailed enormous waste as rail companies built lines almost side-by-side and waged rate wars that destabilized the industry and disrupted transportation. Morgan hosted periodic rail summits at his New York mansion. Amid the smoke of cigars and the acrimony of executives with lesser clout, Morgan would orchestrate truces in current wars and extract promises not to aggress in the future. Financial reporters staked out Morgan’s home; they listened at windows and bribed servants to obtain details from the inner sanctum. They rarely succeeded, but the gist was clear enough, and it inspired a typical headline after one summit: “Railroad Kings Form a Gigantic Trust.”

Morgan detested the publicity. He resented the reporters’ inquisitiveness, and he loathed their cameras, which cast his ugly nose before the smirking gaze of the world. When he could, he insisted that photographers reconstruct his nose with their airbrushes; when he couldn’t, he paid to destroy the negatives. He believed, moreover, that his business was his business, however much it might suit the public interest. Let others do with their money what they chose, and leave him to do with his what he chose.

The distinction between the private and the public became harder to defend after the Panic of 1893 triggered the worst depression in American history to that date. “Men died like flies under the strain,” Henry Adams, a great-grandson of John Adams, wrote of the period. “Boston grew suddenly old, haggard, and thin.” Wage cuts triggered strikes at Homestead, Pa., where steelworkers battled Pinkerton detectives for control of the Carnegie Steel works, and Pullman, Ill., where workers initiated a labor action that paralyzed the country’s rail system. Jacob Coxey led an army of the unemployed in a march to Washington. Graybeards recalled the dark period before the Civil War and wondered if America could hold together. “In no civilized country in this century, not actually in the throes of war or open insurrection, has society been so disorganized as it was in the United States during the first half of 1894,” an editor asserted a short while later. “Never was human life held so cheap. Never did the constituted authorities appear so incompetent to enforce respect for law.”

No one could say just what had precipitated the panic or was causing the depression to persist. But all explanations noted the declining price level the country had experienced since the 1870s. Falling prices pinched farmers and other debtors, since the relative value of the dollars they owed their creditors increased with each passing year, and hence required greater effort to earn. Farmers’ organizations demanded that the government re-level the playing field by expanding the money supply. The Treasury, after a war-induced fling with unsecured paper dollars, clung to the gold standard, promising to redeem the American currency with the yellow metal upon the bearer’s demand. But the farmers’ advocates pointed out that the American economy had grown much faster than the supply of gold. With so many goods vying for so little gold, prices were bound to keep falling. The proposed solution: Supplement gold with silver. The slogans of the silverites were “free silver” and “16 to 1,” by which they meant the free coinage of silver at a ratio of 16 ounces of silver to 1 ounce of gold. If effected, this would have dramatically expanded the American money supply, and reversed the falling prices.

But the mere thought of such inflation terrified creditors, who benefited from the falling prices—which was to say, the strengthening dollar—to the same degree the debtors suffered. Many were tempted to trade their dollars for gold ahead of the feared devaluation; more than a few succumbed to the temptation. As they did so the Treasury’s gold reserve declined. By law and custom the Treasury was expected to maintain $100 million in gold, usually a sufficient cushion against the quotidian buffets of supply and demand. But the extraordinary circumstances after the 1893 panic suggested this wasn’t enough. During 1894 the Treasury’s reserve flirted with the $100 million floor; by year’s end the hoard was barely above the mark. The new year briefly slowed the drain, but at mid-month the pressure on the Treasury resumed. On January 24, 1895, the gold reserve fell to $68 million; one week later it was $45 million.

As large dollar-holders converged on the Treasury and scrambled to convert their paper to gold, the panic resembled runs that had brought down thousands of commercial banks since the depression began. But now the imperiled institution was the federal government. The solvency of the republic was at risk.

The danger to the dollar overwhelmed Morgan’s reluctance to show himself in public. He left the comfort and security of New York, where he was respected, if not exactly loved, and headed for Washington, where his enemies clustered. He traveled by private railcar, to avoid the hostile glares as long as possible.

Grover Cleveland learned he was coming. The president hadn’t invited the banker; even as the country approached the brink, Cleveland hoped something would occur to spare him the ignominy of turning to Morgan. And when Morgan reached the capital, Cleveland tried to keep him at a distance. He sent his secretary of war and closest confidant, Daniel Lamont, to intercept Morgan at Union Station. Lamont said the president would not meet with Morgan; he would find another solution to the problem.

Morgan refused to be put off. There was no other solution, he said. And having ventured this far into enemy territory, he wasn’t going to retreat without accomplishing his mission. “I have come down to see the president,” he told Lamont. “And I am going to stay here until I see him.” He climbed into a cab and drove to a hotel near the White House.

All that evening Cleveland agonized. Morgan’s journey to Washington had been reported in the papers; his presumed intervention heartened investors and diminished the pressure on the Treasury. The president wondered if he could somehow capture the financial benefits of Morgan’s proximity without paying the political costs. Lamont brought word of Morgan’s determination to remain in Washington; Cleveland considered riding out the siege.

Morgan affected nonchalance. Reporters circled his hotel, swarming the entryways and infiltrating the lobby. He remained inside, silent and unseen. His few friends in the capital dropped by to visit; he greeted them one by one. After the last visitor left, he stayed up playing solitaire. Hotel workers later told reporters that the light in his room didn’t go out till after 4 a.m.

But the next morning by 9:00, he was shaved and ready for breakfast. He received with his juice the first reports of the opening of business in New York, and learned that the run on the Treasury had resumed. He hadn’t even lit his post-breakfast cigar when a messenger arrived from the White House. The president would see him.

Dark clouds threatened snow as Morgan hurried across Lafayette Square, shielding his face from the wind—and from reporters—with the upturned collar of his coat. He was shown to Cleveland’s office.

The president’s discomfort was obvious. He spoke of the crisis in terms suggesting he still hoped to avoid a Morgan rescue. Morgan listened briefly, then brought the matter to a head. His sources had told him that the Treasury’s reserve was around $9 million. Other sources revealed that a single investor held a draft of $10 million against the Treasury’s gold. “If that $10 million draft is presented, you can’t meet it,” Morgan declared. “It will be all over before three o’clock.”

Cleveland realized he had no choice. “What suggestion have you to make, Mr. Morgan?”

Officials at the Treasury had been considering a public bond offering; Morgan declared this method too slow. A private sale was necessary, he said. He would gather a syndicate that would take the government bonds and give the Treasury the gold it needed to stay afloat.

Cleveland questioned whether this was legal. Morgan asserted that it was, citing a Civil War statute—number “four thousand and something,” he said—that had authorized President Lincoln to sell bonds privately in emergencies. The law had never been repealed.

Cleveland looked at his attorney general, Richard Olney, and asked if this was so. Olney said he would have to check. He disappeared and then returned, bearing a volume of the Revised Statutes. He handed the book to Treasury Secretary John Carlisle, who read to the group: “The Secretary of the Treasury may purchase coin with any of the bonds or notes of the United States…upon such terms as he may deem most advantageous to the public interest.” Carlisle turned to Cleveland. “Mr. President,” he said, “that seems to fit the situation exactly.”

Cleveland asked Morgan how large a transaction he had in mind. One hundred million, Morgan replied. Cleveland groaned. To the public it would appear that Morgan wasn’t simply rescuing the Treasury but taking over the place. The president said $60 million would have to do.

He then asked the critical question. “Mr. Morgan, what guarantee have we that if we adopt this plan, gold will not continue to be shipped abroad, and while we are getting it in, it will go out, and we will not reach our goal? Will you guarantee that this will not happen?”

Morgan didn’t hesitate. “Yes, sir,” he said. “I will guarantee it during the life of the syndicate, and that means until the contract has been concluded and the goal has been reached.”

Morgan was as good as his word, and his word was as good as gold—quite literally. As soon as news of the rescue flashed along the telegraph lines to New York and London, the gold that the Morgan syndicate pledged to deliver was almost superfluous. The fact that Morgan had become a cosigner on the federal debt was what impressed the markets. Within days the Treasury’s condition stabilized; within weeks the dollar’s danger had passed.

But Cleveland’s troubles were only beginning. Presidents rarely get credit for disasters averted, which the skeptical and partisan can argue would never have happened anyway. The left wing of Cleveland’s party excoriated him for handing control of public finances to a private syndicate headed by the very symbol of capitalist power. Morgan didn’t help Cleveland’s case by stonewalling efforts to make him reveal the profit he had made on the rescue. “That I decline to answer,” Morgan told congressional investigators. “I am perfectly ready to state to the committee every detail of the negotiation up to the time that the bonds became my property and were paid for. What I did with my own property subsequent to that purchase I decline to state.”

Democratic populists didn’t have the votes to compel Morgan, and so turned their wrath against Cleveland. At the Democratic convention the following year they rallied to William Jennings Bryan, who lumped Cleveland with Morgan in the camp of those crucifying mankind on a “cross of gold.” Cleveland, who had led the party out of its post–Civil War wilderness, could only watch in dismay as Bryan led the party back into the wilderness, losing not once—in 1896—but thrice—in 1900 and 1908, as well.

Morgan’s demise took longer. The Treasury rescue burnished his reputation among capitalists, who in 1901 watched in awe as he fashioned the first billion-dollar corporation in American history, the United States Steel trust. Wall Street marched to Morgan’s orders as he stepped into the breach amid the financial panic of 1907, when the nation’s chronic gold shortage triggered a run on undercapitalized trust banks.

With President Theodore Roosevelt off shooting game in Louisiana for two weeks, Morgan, then 70, operated as a self-appointed financial crisis manager from his Madison Avenue brownstone. He saved the New York Stock Exchange by demanding that New York bankers float it a $24 million loan. He organized another $30 million loan to keep New York City from defaulting on its payroll and debt obligations. As two major trust companies teetered on the brink of failure, Morgan summoned some 50 bank presidents to his library on a Saturday night and closed the door. He didn’t let them out until dawn on Sunday, after stipulating how much each would have to contribute to a $25 million bailout package.

Morgan’s efforts kept the financial system from disintegrating. Nonetheless, his critics maintained their hostile fire. After the progressives—the heirs to the populists—seized control of Congress in the 1910 elections, they launched a probe of what they called the “money trust.” Morgan was summoned to testify, but offered only the vaguest answers to queries as to how he made decisions to provide or withhold credit. He denied that he or anyone else exerted inordinate influence on American finance. He declared that the most important thing in business was not money or property, but character. A man might have all the collateral in the world, but without character he wouldn’t get a loan—at least not from Morgan. “I have known a man to come into my office,” Morgan said, “and I have given him a check for a million dollars when I knew he did not have a cent in the world.”

The committee wasn’t buying, and its resulting report delineated a network of interlocking directorates among the country’s banks, with J.P. Morgan & Co. at the center. The report decried the monopoly power this afforded Morgan and his associates, and warned of future crises worse than those of the recent past, concluding, “The peril is manifest.”

Morgan slipped out of the country amid the furor and steamed to Europe in the spring of 1913 for an annual art-buying holiday. His traveling companions noted that he seemed unusually anxious and depressed. In Italy he contracted a fever that abruptly proved fatal. His physicians expressed puzzlement, but his colleagues blamed the death on the weight of public opprobrium.

Morgan’s death neatly marked the passing of an age in American banking. The exposé of his financial power provided grist for the mills of reform, which in December 1913 produced the Federal Reserve Act, wresting control of banking and the nation’s money supply from the likes of Morgan and delivering it to the new Federal Reserve System.

In the first decade of the 21st century, when panic again seized the financial markets, it was the Fed that rode to the rescue with a massive monetary stimulus. The world had changed since Morgan towered like a colossus over Wall Street. But one thing remained the same. If Morgan had lived to see the political flogging Fed chief Ben Bernanke was forced to endure for his decisive action on behalf of

the bankers, he would have smiled knowingly.

H.W. Brands is the author of The Money Men and the forthcoming American Colossus: The Triumph of Capitalism.