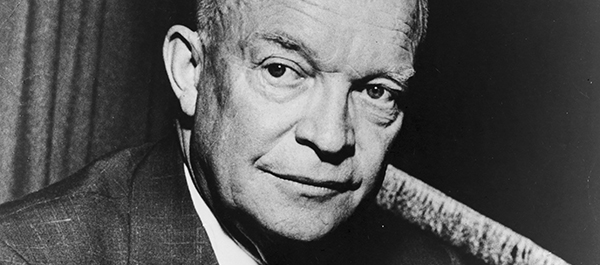

Eisenhower scholars have spent much time correcting the record of his presidency, most of it distorted by biased historians and antagonistic pundits. Ike’s legacy in civil rights is still the issue that spurs the most debate. Here are some irrefutable facts about what he did.

Recommended for you

First, Eisenhower desegregated the District of Columbia. When he took office in 1953, an African-American visitor to downtown Washington could not rent a hotel room, buy a meal, attend a movie or easily find a drink of water or a restroom outside the city’s black neighborhoods. On the president’s orders, the Justice Department successfully argued the desegregation of D.C. restaurants before the Supreme Court; one African-American newspaper exuberantly declared, “Eat anywhere!” Eisenhower enlisted Hollywood moguls to pressure movie theaters to desegregate, and he and the first lady refused to attend segregated activities in the city. By the end of his first year, segregation of public facilities had virtually ended.

Harry Truman’s 1948 executive order to desegregate the armed forces had been only feebly enforced, but Eisenhower fully implemented it. By October 30, 1954, not a single segregated combat unit remained. After two years in the Oval Office, Ike had desegregated the Veterans Administration and military bases in the South, including federally controlled schools for military dependents—prior to the Supreme Court’s landmark May 1954 Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision.

In 1955, Eisenhower named E. Frederic Morrow as the first African-American executive assistant in the White House. No previous president had ever made such an appointment. He made other strong pro-desegregation appointments, including Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr., a key civil rights adviser who was instrumental in desegregating the nation’s capital.

Eisenhower established a presidential committee to negotiate nondiscrimination agreements with government contractors and appointed a second committee to end discrimination in government departments and agencies. While these committees had no statutory authority, Eisenhower invested them with more executive authority than the committees instituted by any previous president; for example, he tapped Vice President Richard Nixon to chair the contracts committee.

Eisenhower proposed, fought for and signed the Civil Rights Act of 1957—the first civil rights legislation in 82 years. The president presented the comprehensive bill in his 1957 State of the Union address. Contrary to the popular myth that Senate majority leader Lyndon B. Johnson’s backroom dealing saved the Civil Rights Act from defeat, the bill was not Johnson’s triumph; it was Eisenhower’s. Johnson led Southern senators in a fight against a provision that empowered the attorney general to sue in federal court to protect a broad range of civil rights, including school desegregation.

He forced Eisenhower to capitulate or face the prospect of passing no bill at all. Johnson and the Southerners also added an amendment guaranteeing jury trials for civil rights violators, a requirement that, given all-white juries in the South, made conviction unlikely. Ike pushed back and won a compromise that softened the amendment. Thanks to Eisenhower’s leadership, 37 Senate Republicans supported the final version of the 1957 bill, but the “Master of the Senate,” Johnson, could muster only 27 Democratic votes.

The legislation established the Civil Rights Commission and the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, which have publicized and prosecuted civil rights violations ever since. Eisenhower had broken the Southern stranglehold on civil rights legislation and, with passage of a voting rights act in 1960, set the stage for the groundbreaking legislation of 1964-65.

Eisenhower’s judicial appointments constituted his greatest contribution to African-American civil rights. On September 30, 1953, Eisenhower selected California Governor Earl Warren—a man he knew was liberal on race—to replace Fred Vinson, who had died unexpectedly, as chief justice of the United States.

With Congress in adjournment until January, the president made a recess appointment, freeing Warren to work immediately on the Brown school desegregation case, which the Supreme Court would hear in its December 1953 session. On May 17, 1954, Warren announced the court’s unanimous decision, striking down its 1896 separate-but-equal ruling, Plessy v. Ferguson. A year later, in Brown II, the Eisenhower administration’s Justice Department—in a brief Ike personally edited—proposed that school districts be required to submit desegregation plans within 90 days. But the Supreme Court chose to mandate desegregation “with all deliberate speed”—a phrase NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall declared meant “S-L-O-W.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

When the first Brown ruling was announced, Eisenhower immediately ordered the District of Columbia commissioners to develop a desegregation plan for the city’s schools; that was accomplished within a week. In a press conference, Eisenhower made a soldierly pledge to enforce the decision without commenting on the merits of the case—a move that many have misinterpreted as disagreement with the ruling. But in addition to Earl Warren, Ike appointed to the Supreme Court four stalwart supporters of desegregation: John Marshall Harlan II, William Brennan, Charles Evans Whittaker and Potter Stewart.

Eisenhower also refused to appoint known segregationists to the lower federal courts. In an attempt to depoliticize the appointment process, the president and Attorney General Brownell moved it from the White House to the Justice Department and instituted American Bar Association assessment of potential nominees. When Brownell left office in 1957, Eisenhower continued to appoint pro-desegregation judges in the South. President John F. Kennedy, in contrast, returned to appointing segregationists. As a result, the civil rights movement migrated from the courts to the streets.

On September 24, 1957, Eisenhower sent the 101st Airborne Division into Little Rock, Arkansas, to enforce a federal court order by one of his own appointees to desegregate Central High School. Governor Orval Faubus had deployed the Arkansas National Guard to bar nine black students from attending the school. After meeting with the president and agreeing to change the orders of the Guard to protect the black students, Faubus instead withdrew the troops, leaving the students at the mercy of the mob. That is when Eisenhower acted. In a televised address to the nation on the night of the 24th, Eisenhower vowed, “The president and the executive branch of government will support and ensure the carrying out of the decisions of the federal courts, even, when necessary, with all the means at the president’s command.”

For decades, historians have assumed, thanks to the important legislation passed in 1964–65, that John F. Kennedy and Lyndon V Johnson were the era’s great civil rights leaders and that Eisenhower failed to “speak out” on the issue. But Ike’s record speaks for itself. JFK and LBJ did not commit to the cause until 1963, when horrific violence in the South compelled them to. It is time, finally, to bury the myth that Ike did nothing on civil rights. In the 1950s, Dwight Eisenhower was more progressive in advancing African-American civil rights than Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy or Lyndon Johnson.

David A. Nichols is the author of A Matter of Justice: Eisenhower and the Beginning of the Civil Rights Revolution and Ike and McCarthy: Dwight Eisenhower’s Secret Campaign Against Joseph McCarthy.