Air Force Maj. Fred V. Cherry, the pilot of an F-105D Thunderchief shot down by anti-aircraft fire on Oct. 22, 1965, was sitting in a dark 10-by-12-foot cell in North Vietnam. His left foot was wrapped in a cast and his left arm in a sling. Suddenly the cell door opened, and a guard ushered in another prisoner of war, Navy Lt. Porter Alexander Halyburton, a radar intercept officer on a two-seater F-4B Phantom II hit by anti-aircraft fire on Oct. 17, 1965. Cherry was the first African American service member captured in North Vietnam, while Halyburton came from a middle-class Southern family that employed Black servants.

A prison guard ordered Halyburton: “You must take care of Cherry.”

Neither man knew what to make of the other. Cherry, 37, explained that he was an Air Force major who flew an F-105. Halyburton, 24, found that hard to believe as most Blacks he knew worked as laborers. He had never met an African American who outranked him. Cherry didn’t believe his new cellmate was American. He presumed that Halyburton was a Frenchman left over from France’s colonial rule, which ended in 1954, and most likely worked for the North Vietnamese as a spy.

The North Vietnamese Attempt to “Divide and Conquer”

During their first night together at Cu Loc Prison, Halyburton tried to make conversation by asking Cherry questions about his background, flight origin and the date he was shot down, which seemed to confirm Cherry’s suspicions that his cellmate was a spy.

Yet it didn’t take long for Cherry to recognize the North Vietnamese strategy in putting them in the same cell.

The guards knew both men were from the South, he recalled in an oral history collection of Black Vietnam War veterans, edited by Wallace Terry and published in 1984. “They figured under those pressures, we couldn’t possibly get along—a white man and a Black man from the American South.”

Prison authorities believed that if they couldn’t get Cherry and Halyburton to cooperate through torture, harassment or isolation, they would play upon the turbulent race relations in America by using Cherry as a propaganda tool to exploit racial tensions in the U.S.

He was repeatedly told by his interrogators that whites were racists and colonizers and that he had more in common with Asians. The guards evoked the words of Malcolm X, who openly criticized American involvement in Vietnam.

Despite their captors’ effort to exploit the racial divide, the two Americans gradually established trust in one another and developed a close bond as they shared stories about their home, families and the military service that had brought them to this point.

Cherry’s Journey to Vietnam

Cherry, the youngest of eight children, was born in Suffolk, Virginia, on March 24, 1928, of African American and Native American heritage. He grew up in a poor farming family that lived in a swampy area during the Great Depression, a time when racial segregation and discrimination were strictly enforced by state Jim Crow laws.

Although poor Blacks and whites lived side by side in Cherry’s farming community, Blacks weren’t regarded as equals. “You go over to the white farmhouse to get some homemade butter, and you had to ‘Miss’ and ‘Mister’ them,” Cherry said in his oral history interview. “Whites always called Blacks by their first name. It was sort of understood you had your place.”

In Cherry’s racially segregated public schools, white children rode half-full buses, while he and his siblings walked three miles to their school. In the impoverished agrarian South, where survival often trumped protest and confrontation, Cherry was taught that progress was possible through hard work and tenacity—if you were willing to endure the personal affronts.

As a young man, Cherry became fascinated with U.S. Navy aircraft practicing carrier landings at a nearby base and later found inspiration in the stories of the Tuskegee Airmen, Black fighter pilots in World War II. Cherry went to Virginia Union University, a historically Black college in Richmond. Before graduating he took qualifying examinations for flight school at Langley Air Force Base in nearby Hampton. He was the only African American among the 20 applicants and achieved the highest score.

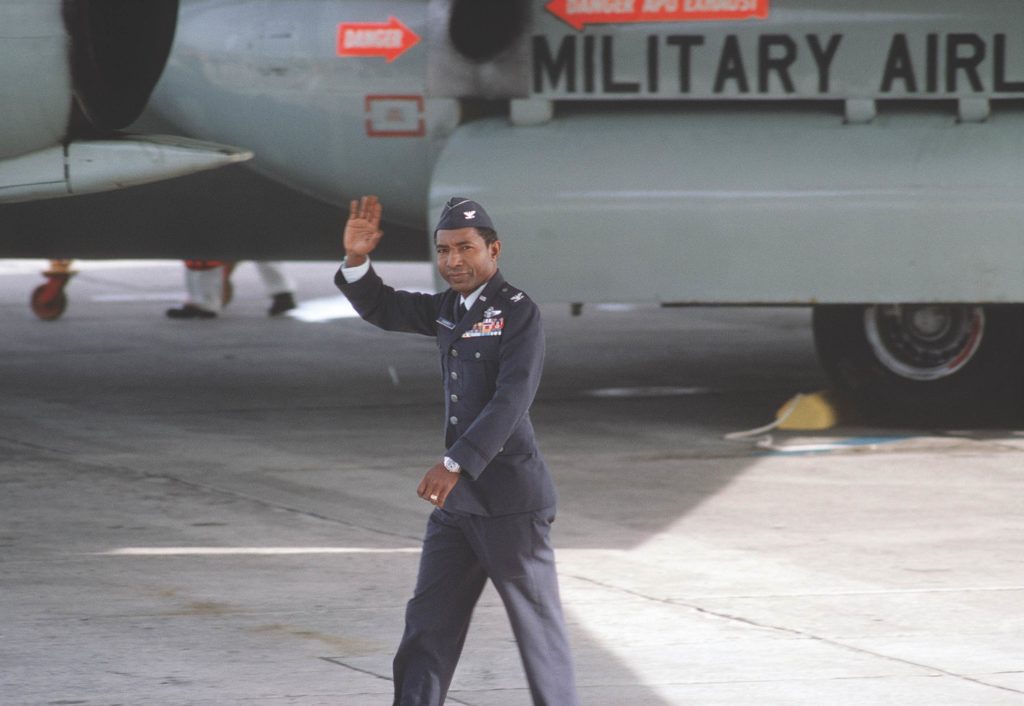

Cherry flew more than 50 combat missions during the Korean War and rose to the rank of major after serving in various posts at home and abroad. He was deployed to Southeast Asia in the early days of the Vietnam War.

On his 52nd combat sortie over North Vietnam, Cherry led a flight of four F-105D Thunderchief fighter-bombers of the 35th Tactical Fighter Squadron that took off from Takhli Royal Thai Air Force Base on a mission to destroy a surface-to-air missile installation 15 miles northeast of Hanoi. After crossing the Laotian-Vietnamese border, Cherry descended to treetop level, flying low to avoid radar detection. Just three minutes from his target, he saw muzzle flashes from the rifles of enemy ground troops. Cherry then heard a loud thump. His aircraft shook and swerved. Locking the control stick between his legs, the pilot used both hands to try to steady his Thunderchief as the plane jerked.

Cherry saw the SAM installation ahead with several missile-launching batteries in a circular formation. Undeterred, he pressed the attack, releasing his payload of cluster bombs on the target and setting off series of explosions. In his rearview mirror, Cherry saw the SAM site being consumed by massive fireballs.

Straining to gain altitude in his damaged F-105, he immediately headed for the Gulf of Tonkin 40 miles east, where he intended to bail out and be picked up by the Navy. Suddenly, smoke began pouring out of the instrument panel. Multiple warning lights flashed. Any hope of reaching the sea was gone. The aircraft exploded and flew out of control.

Cherry ejected from his crippled Thunderchief at 400 feet and 600 mph. The violent expulsion from the high-speed aircraft left him with a broken left wrist, a broken left ankle and a shattered left shoulder. He parachuted onto a small grassy hill just two minutes from the coast. Almost immediately, the injured American pilot found himself surrounded by a dozen armed Vietnamese militiamen and civilians.

Cherry was disarmed, stripped of his gear and marched off with his elbows tied behind his back. The constraint caused excruciating pain to his broken shoulder. The captive was driven to what appeared to be a school and interrogated under torture for hours. Throughout his grueling captivity, Cherry firmly adhered to the U.S. Military Code of Conduct, giving only his name, rank, serial number and date of birth.

That night, he was taken to Hoa Lo Prison, whose Vietnamese name translates roughly to “fiery furnace” and was infamously known to POWs as the Hanoi Hilton, a caustic reference to the torture that took place there. The more Cherry refused to cooperate, the more abusive his interrogators became. His arms were twisted behind his back and forced upward, pulling his already shattered left shoulder from its socket. Cherry endured daily interrogations and torture over the next few days. His left ankle became badly swollen and his shoulder contorted, but he was denied medical care as punishment for his refusal to cooperate.

One month after his capture, Cherry was transferred to Cu Loc Prison, sardonically dubbed by the POWs as “the Zoo,” where he would soon meet Halyburton.

Halyburton’s Journey to Vietnam

Halyburton, born Jan. 16, 1941, grew up in the small college town of Davidson, North Carolina, then an intellectual suburbanite’s enclave steeped in patriotism, Southern charm and insidious racism.

He was raised by his mother and grandparents in a town that largely opposed desegregation. His community and, by extension, his family believed that Blacks were intellectually inferior and could only do manual labor.

Halyburton’s grandfather, although regarded as being charitable and respectful toward his Black housekeeper and her family, did not treat them as equals. They were welcome to enter the home through the front door but were not allowed to share the family’s bathrooms.

Halyburton attended the Sewanee Military Academy in Tennessee and Davidson College. There he was inculcated with an appreciation for discipline and structure. Yet his interests also included literature, poetry and the power of prayer.

He considered going into journalism, but with the escalating Cold War and the possibility of being drafted, Halyburton decided to volunteer. Inspired by a fraternity brother’s experiences as a naval aviator flying the F-4 Phantom II, he enlisted in the Navy after graduating in 1963.

“Haly,” as his buddies called him, completed the preflight program on Oct. 10, 1963, and was later assigned to fighter squadron VF-84 aboard the carrier USS Independence. There he trained as a radar intercept officer, which made him responsible for navigation and identifying targets while riding in the backseat of a Phantom.

On Halyburton’s 75th mission of the war, aircraft from the Independence took part in a large airstrike to destroy a rail bridge at Thai Nguyen, 75 miles north of Hanoi, the farthest north Halyburton had ever flown. Anti-aircraft fire hit his F-4. Halyburton ejected before the plane crashed, but his pilot, Lt. Cmdr. Stanley Olmsted, was killed.

As his parachute drifted down, Halyburton could hear groundfire directed at him from a nearby village. After landing, he attempted to make his way up the nearest hill, hoping to be rescued by Navy helicopters, but he was soon captured by North Vietnamese militia and sent to the Hanoi Hilton.

Halyburton endured days of interrogations that lasted for hours at a time. Then he was given a choice: Cooperate and receive better treatment or refuse and be taken to a place where conditions were worse. Thinking there couldn’t possibly be anywhere worse than the Hanoi Hilton, he chose the latter. Halyburton was transferred to Cu Loc Prison, “the Zoo,” on Nov. 27, 1965.

Shared Sufferings

On Dec. 24, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson paused the bombing campaign and sent a 14-point peace plan to North Vietnam’s President Ho Chi Minh. In the event that peace was declared, the North Vietnamese were to provide injured American POWs with medical care.

Cherry finally had surgery on his shoulder and was placed in a torso cast. Yet without the benefit of antibiotics, the incisions became infected. On Jan. 31, 1966, negotiations on the 14-point peace plan broke down and the fighting resumed. Afterward, Cherry was left to rot in his cell with no medication or treatment.

Although Halyburton was able to shower periodically, Cherry wasn’t allowed to shower for four months due to his condition. Halyburton fed and bathed his cellmate, changed his dressings and cleaned his wounds. One day he noticed that ants had invaded Cherry’s scalp where mounds of gunk had developed. Standing with him in a quarter inch of slime in a makeshift cold-water shower, Halyburton undressed Cherry and soaped and scrubbed his hair again and again until the greasy gobs and dead ants floated in the slime around their feet.

When Cherry developed a fever and began hallucinating, Halyburton begged prison authorities to save Cherry’s life. Not wanting their only Black American POW and valuable propaganda asset to die, the North Vietnamese relented, and Cherry underwent a series of crude surgeries at a hospital to treat his infections.

As the two men struggled to survive, Halyburton realized that he too had benefited from their time together. The Navy lieutenant had neared a dangerous abyss of despair during his torturous days in isolation before meeting Cherry. Thus, while Halyburton had saved Cherry’s life, Cherry had given Halyburton a purpose and the will to persevere.

In an email to journalist James S. Hirsch, author of 2004 book about the two POWs, Halyburton wrote: “Caring for Fred…I realized how trivial [my concerns] were by comparison and how he bore his pain and suffering with such dignity…The task of caring for him gave a definite purpose to my immediate existence…I received much more from him than I was able to give.”

On July 6, 1966, 52 POWs, including Halyburton, were paraded through the streets of Hanoi in a propagandistic attempt to demonstrate the North Vietnamese people’s anger at the U.S. bombing campaign. Thousands of agitated civilians descended upon the American captives and attacked them with bricks, bottles, stones, garbage and fists. Halyburton returned to his cell battered and bruised.

Shortly after Halyburton’s brutal beating, Cherry was brought back from the hospital, where he had undergone a “sadistic” cutting of dead flesh without anesthesia. As his blood dripped all over the floor, Cherry collapsed into the arms of his friend. “Fred,” Halyburton exclaimed, “what in the world did they do to you?” Both men remembered that they shed “a tear or two” that night as they dwelled on their sufferings.

Four days later, on July 11, 1966, Halyburton was transferred to another prison, known as the Briarpatch, 33 miles northwest of Hanoi. “Tears started to roll down my eyes,” Cherry recalled. “We cried. And he was gone…I never hated to lose anybody so much in my entire life. We had become very good friends. He was responsible for my life.”

Discussing his friendship with Halyburton years later in an email to Hirsch, Cherry said: “He was white and he was from the South, but he taught me that you can grow up in that environment and separate the good from the bad and the right from the wrong. He was one who did that.”

After Halyburton’s departure, the North Vietnamese continued to press Cherry to make public statements regarding racial intolerance in the United States, but he refused. Cherry spent 702 days in solitary confinement and was tortured for 93 days in a row.

Lifelong Friendship

On Jan. 27, 1973, the Paris Peace Accords were signed after years of negotiations. As part of the agreement, all American POWs were to be released from captivity. After more than seven years in hell, Cherry and Halyburton were going home.

Cherry attended the National War College in Washington and later worked at the Defense Intelligence Agency. He retired from the Air Force as a colonel in 1981. In July 1987, President Ronald Reagan appointed Cherry to the Korean War Veterans Memorial Advisory Board. He later became CEO of Cherry Engineering and Support Services and director of SilverStar Consulting. In 1999, Cherry was featured in a public television documentary, “Return with Honor,” narrated by Tom Hanks. The film looked at the American POW experience in Vietnam.

Halyburton completed his graduate work in journalism at the University of Georgia and was assigned to work at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. He retired from the Navy in 1984 with the rank of commander. Halyburton stayed at the Naval War College, teaching various subjects including strategy and policy and the Military Code of Conduct.

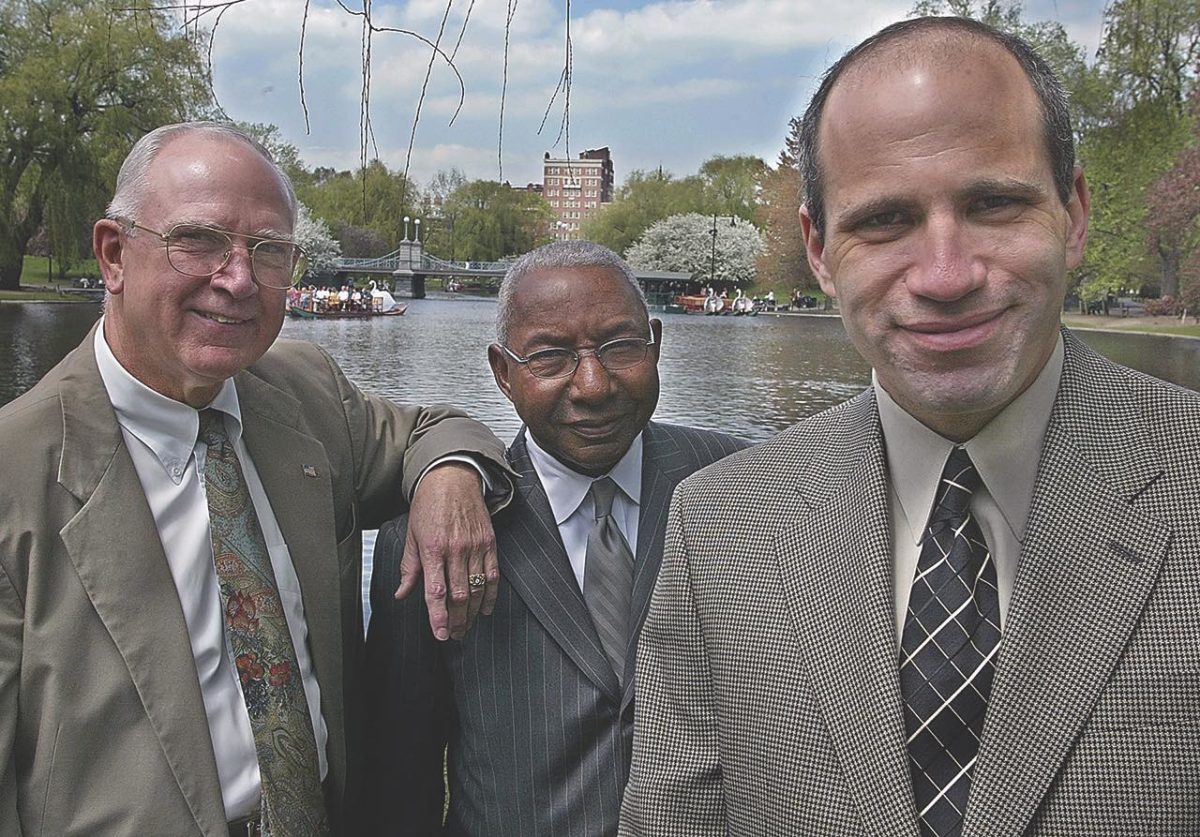

Cherry and Halyburton remained lifelong friends. They often gave talks together on their experiences in Vietnam. Cherry died of cardiac disease on Feb. 16, 2016. Two years later, his hometown honored Cherry by naming a Suffolk middle school after him. Cherry is buried at Arlington National Cemetery, where he was laid to rest with full military honors. Halyburton resides in Greensboro, North Carolina, with his wife, Martha, and their three children.

Daniel Ramos is a freelance writer who focuses on military history topics. He has written Fighting for Honor, about the roles of five ethnic groups in the military, currently being edited for publication. Ramos works at September 11 Museum and Memorial in New York as an interpretive guide/educator.

This article appeared in the June 2022 issue of Vietnam magazine.