Volunteers struggle to identify occupants of anonymous graves at Fredericksburg

THE OFFICER STOOD OVER the freshly exhumed grave with a pencil and ledger in his hands. He told others to search the remains as he struggled to decipher the crude etching on a weathered piece of wood. The faded and worn lettering seemed to read “W.A.W.” A worker called the officer’s attention to a hat badge indicating the deceased was from New Hampshire, but no additional identifiable information was found, prompting the officer to record in the ledger book, “Grave #1221, W.A.W., NH, removed from O’Bannon’s Farm.” A pile of bones and decayed clothing was then placed into a rough wooden coffin for transport to the newly established Fredericksburg National Cemetery.

The aforementioned scene was repeated more than 15,000 times in Fredericksburg, Stafford, and Spotsylvania counties from 1866 to 1868. During this period, U.S. Army reburial details scoured the region cataloging and reinterring the remains of Union soldiers. Sadly, more than 12,000 of the graves were simply marked “Unknown”—the result of no standard issue identification for the soldiers, no protocol for properly identifying or marking graves, and the sheer magnitude of casualties incurred on a landscape that witnessed four of the war’s costliest battles.

Upon the war’s culmination, the federal government established national cemeteries throughout the South, to better administer and honor the multitude of Union dead there. Army officers were assigned to supervise parties of contracted workers, some former slaves, to reinter the remains of Union soldiers in these cemeteries. Despite the inherent difficulties, they were to establish identification to the best of their ability, and it appears they took this responsibility quite seriously.

Unfortunately, many found it nearly impossible to discern any semblance of identity from decomposing corpses that had been buried haphazardly several years prior. But there were exceptions. Some rudimentary grave markers actually survived relatively unscathed, making the ID process fairly straightforward. There were many graves with only a partially discernible marker; a soldier with his last name or initials stenciled on their equipment or uniform; an officer whose rank and unit could be determined from his insignia. Instead of simply denoting these partially identified men as “unknown,” the officers supervising the reburial details made a point to record any tidbits of information. As a result, the Fredericksburg National Cemetery has gravestones engraved with only initials or a first or last name. The rank or state may also be noted, and the original site of the grave documented.

Fast forward 152 years later, as Steve Morin, a volunteer at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park, pores through the yellowed pages of an antique book, cross-referencing it with his iPad. A retired FBI research specialist and student of the Civil War, Morin is attempting to determine the identity of an unknown soldier. He is not using DNA to perform this task, but rather a combination of rosters, books, and online resources.

Morin scrutinizes enlistment and payroll records, unit rosters, pension applications, and a multitude of other sources. He must also take into account misspellings or misinterpretations of writing from more than 150 years ago. When a solid deduction is made based on all available evidence, the outcome is denoted in the Fredericksburg National Cemetery records.

Another researcher assisting with the project is Michael Taylor, a midshipman at the U.S. Naval Academy. Taylor was inspired to take this on after visiting the Fredericksburg battlefield with his fellow midshipmen in 2018. Taylor was struck by the extent of unknown graves in the national cemetery—more than 12,000—and asked park staff if there was any way to identify these soldiers. When informed of the arduous and complicated process involved, Taylor was not deterred. Within a week, he had delved into digital resources provided by the National Park Service and came up with promising leads. A year later, his work has resulted in nearly 100 corrections and probable identifications for these previously unknown Civil War soldiers.

It is remarkable to consider that when the Army reburial parties went about their grim task more than 150 years ago, every possible effort was made to identify the fallen. Even if it entailed only part of a name or a state of origin, expectations were that the task would be completed some day. Otherwise, why bother inscribing “W.A.W.” on a gravestone? Now, with vast archives and multitudes of records available at a few keystrokes, the seemingly impossible is viable. Persistent research allows us the opportunity to fulfill the aspirations of our forebears by finally identifying these Civil War dead.

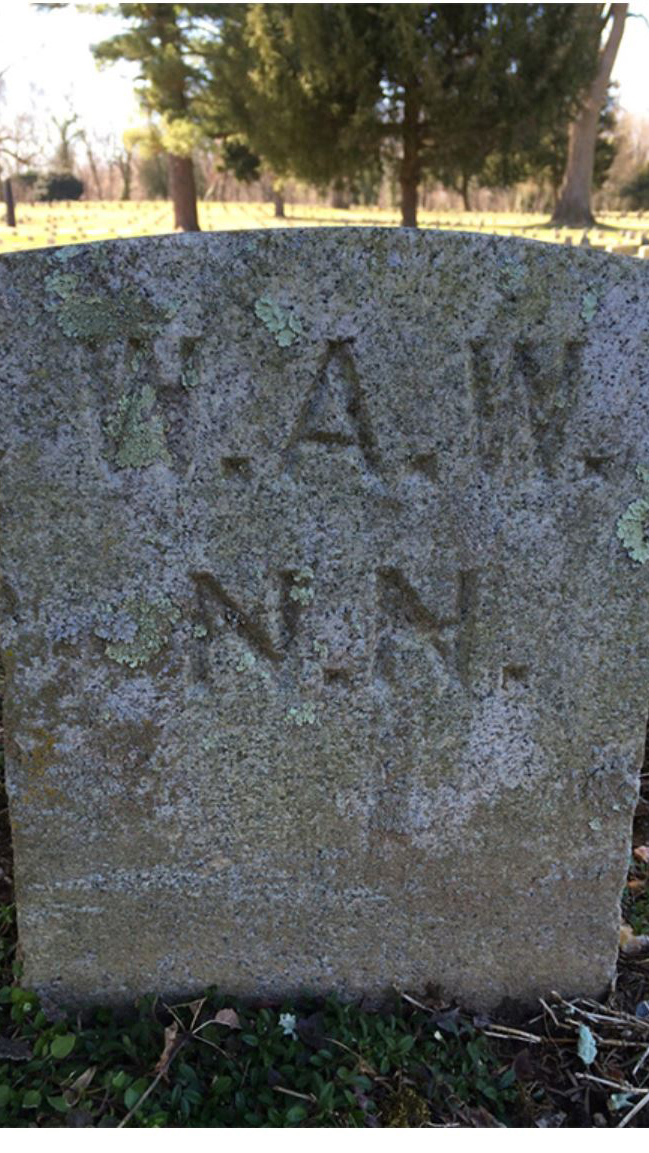

Today, one gravestone in the Fredericksburg National Cemetery is still inscribed with the same ambiguous lettering, “W.A.W.” National Park Service policy prohibits correcting gravestones for “errors of fact”; however, after extensive research by Morin, the cemetery roster—maintained by the National Park Service and available to the public—indicates this grave likely belongs to Private George A. Wheeler of the 5th New Hampshire Infantry. Documentation indicates a soldier from New Hampshire named Wheeler was wounded at Fredericksburg, removed to a field hospital, and died a few days later. Perhaps his comrades crafted the rudimentary marker that a reburial detail found four years later. Their efforts, while diminished by the elements, later provided at least some vague information associated with these remains, eventually enabling an amateur historian to piece together the story of an otherwise unidentifiable casualty of our nation’s costliest conflict.

The important work done by Morin, Taylor, and others was highlighted at the Fredericksburg National Cemetery’s Luminaria on May 25, 2019. For the past 23 years, local scouts have lit more than 15,000 candles on Memorial Day weekend, one for every soldier interred at the cemetery. The 2019 program was uniquely different, however, as attendees were encouraged to visit the graves of several previously unknown soldiers and learn about the remarkable process it took to have their stories finally told.

Peter Maugle is a Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park historian. This post first appeared on the park’s “Mysteries & Conundrums” blog in May 2019 and was published in the January 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.