Alabama cavalrymen spearheaded General Sherman’s March to the Sea.

When Major General William Tecumseh Sherman prepared to set out from Atlanta in the fall of 1864, he tapped the 1st Alabama Cavalry—a regiment of White volunteers recruited from within the heart of the Confederacy—for a key role in the campaign to come. From the commencement of hostilities, United States military and political leadership had sought loyal white Southerners willing to carry the torch of Union to the seat of secession. Now, the 1st Alabama would help to do so. Who were these men? How did they come to reject the Confederacy and embrace the Union in the most uncompromising terms? And how does their turn at the head of Sherman’s army, helping Uncle Billy bring his brand of hard war to the Deep South, add to our understanding of one of the war’s most infamous chapters?

In deploying the 1st Alabama, Sherman made it clear that he did not make war on the South; he made war on disloyalty and treason. Many of the White Southerners who joined the 1st Alabama exhibited a marked hostility toward the secessionist planter class that had arrogated to themselves the lion’s share of political and economic power in the region and brought on the crisis. A number had already suffered serious depredations at the hands of Confederate partisans before the appearance of Union forces in 1862 and sought revenge whenever they had the opportunity. Sherman determined to give them one when he unleashed them in Georgia.

The core of the 1st Alabama Cavalry hailed from the northern section of the state for which it was named. Unlike the black belt of Alabama, which contained the majority of its slaveowners and enslaved people, the upcountry counties at the foot of the Appalachian Mountains displayed a marked ambivalence—if not pronounced opposition—to secession in the winter of 1860-61. Upcountry residents, explains historian Margaret Storey, were often only marginally part of “Alabama’s staple crop and slave economy,” and had far less frequent contact with African Americans or people who were not smallholding farmers like themselves.

Many hill country neighborhoods remained quite insular. As a result, the election of a Republican president and the prospect of the abolition of slavery—as utterly unpalatable as the concept undoubtedly seemed to them—did not amount to a justification for the dissolution of the Union as it did in other parts of the Deep South. Northern Alabama’s geographic isolation and unusual economic and social circumstances fostered a hidden wellspring of Unionism in the heart of the Confederacy. After the ordinance of secession passed, many White Alabamians continued to resist the imposition of Confederate authority—even in the state where the country officially came into existence—and welcomed the Union Army as liberators when elements first began to arrive in 1862.

In February of that year, after an early foray up the Tennessee River, Admiral Andrew H. Foote reported to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that “Union sentiment in…North Alabama [is] very strong,” and added that he would call for an infantry regiment to accompany the next gunboat up the river, “which will aid the loyal people…to raise Union forces within their borders. J.R. Phillips, a 26-year-old farmer from Fayette County, was one of those holding out for such an opportunity. He had suffered terrific abuse from Confederate neighbors over the course of 1861, but wrote that he “cherished the hope that Uncle Sam would surely put them all to death at an early day, and I stood it the best I could.” He explained that, “it was firmly fixed in my mind that I would never go back on ‘Old Glory.’ I had heard too much from my old grandparents and Aunt Jennie about the sufferings and privations they had to endure during the Revolutionary War to ever engage against the ‘Stars and Stripes.’”

By the summer of 1862, following a series of hard-fought victories, the Union Army had established a foothold deep within the Confederacy and could boast more than 100,000 soldiers in Mississippi alone. This allowed beleaguered Unionists to begin to come out of the woodwork. Like Foote, Colonel Abel D. Streight was moved to comment on the dogged Unionist sentiment he encountered. “[I]f there could be a sufficient force in that portion of the country to protect these people,” he said, “there could be at least two full regiments raised of as good and true men as ever defended the American flag….They have been shut out from all communication with any thing but their enemies for a year and a half, and yet they stand firm and true.”

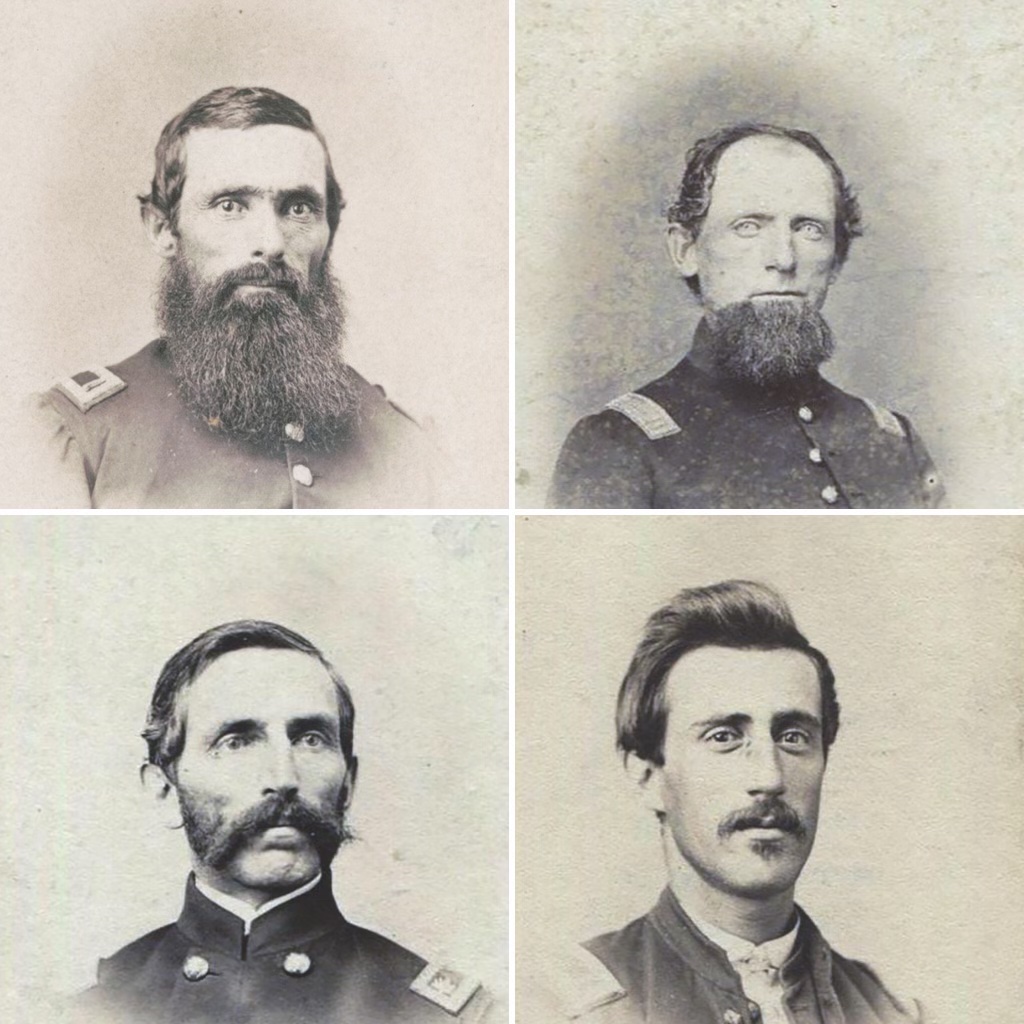

As soon as Federal troops had firmly established themselves at Corinth, Miss., White and Black refugee supporters of the Union started to filter into the lines, often taking great risks to do so. By the fall, there were enough to incorporate a regiment of volunteers. Part of a larger reorganization resulting in the creation of the 16th Corps, the 1st Alabama Cavalry was officially organized in October and mustered into service on December 18. Ever-resourceful Brig. Gen. Grenville M. Dodge spearheaded the effort, and would eventually assign one of his understudies, George E. Spencer, to the regiment’s command. J.R. Phillips, one of those who made it through the lines, enlisted in Company L. “Once in uniform, mounted, well armed and equipped with everything we needed,” he remembered, “one cannot imagine how happy and brave we all felt…we felt like we could whip the whole Rebel Army.”

Initially, the 1st Alabama Cavalry engaged in typical mounted assignments such as reconnaissance and short-range raids. In April 1863, several companies of the 1st participated in Streight’s Raid, an ill-fated cavalry operation aimed at destroying portions of the Western & Atlantic Railroad running between Atlanta and Chattanooga. Poorly planned and executed (the men rode mules), it ended in embarrassment. Four regiments of Confederate cavalry led by Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest quickly caught up with Streight and pursued him and his men across Alabama. Through a clever piece of deception typical of Forrest, the Confederates tricked Streight into thinking he was outnumbered and induced him to surrender his command near the Georgia border.

The Confederate press, made aware that among those captured were White Alabamians fighting for the Union, excoriated them as rank traitors and Tories. “No punishment is too great for such wretches,” declared the incredulous Montgomery Daily Advertiser, “and if justice has her own they will speedily grace the gallows.” Despicable as they undoubtedly were, the editorial argued, Northerners “are angels of light as compared with the craven scoundrels who have turned against their own mother, and engaged in the work of robbery and outrage on their neighbors.”

Confederates expressed bewilderment and rage at the existence of these internal enemies. On a different occasion, after clashing with the 1st Alabama near the Mississippi border in October 1863, Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Ferguson wondered at the fact that, “in the very center of the Confederacy,” he had found “men wearing the enemy’s uniform, killed—as some were—within [a] half mile of their own houses.” Ferguson hopefully but wrongly reported to his superior Maj. Gen. Stephen D. Lee that he had “succeeded in effectually destroying the First Alabama Tory Regiment.” He would encounter them again, when he offered ineffectual resistance to Sherman’s march through Georgia.

The 1st Alabama increasingly engaged in hard war tactics as the war dragged on. At one point, Colonel Spencer informed a “rough” pro-Confederate Alabama woman that his regiment, “were the children of Israel bringing the plague on them.” In 1864, the regiment was placed under the command of General Sherman, and continued to hone their notorious reputation during the campaign against Atlanta. They saw action at Resaca, Dallas, Kennesaw Mountain, and Jonesboro, establishing their pedigree as a reliable and effective cavalry unit. When Sherman called upon the 1st Alabama to play a prominent role in his March to the Sea, and selected a portion of Company I as his personal escort, he had both symbolic and pragmatic reasons for the choice.

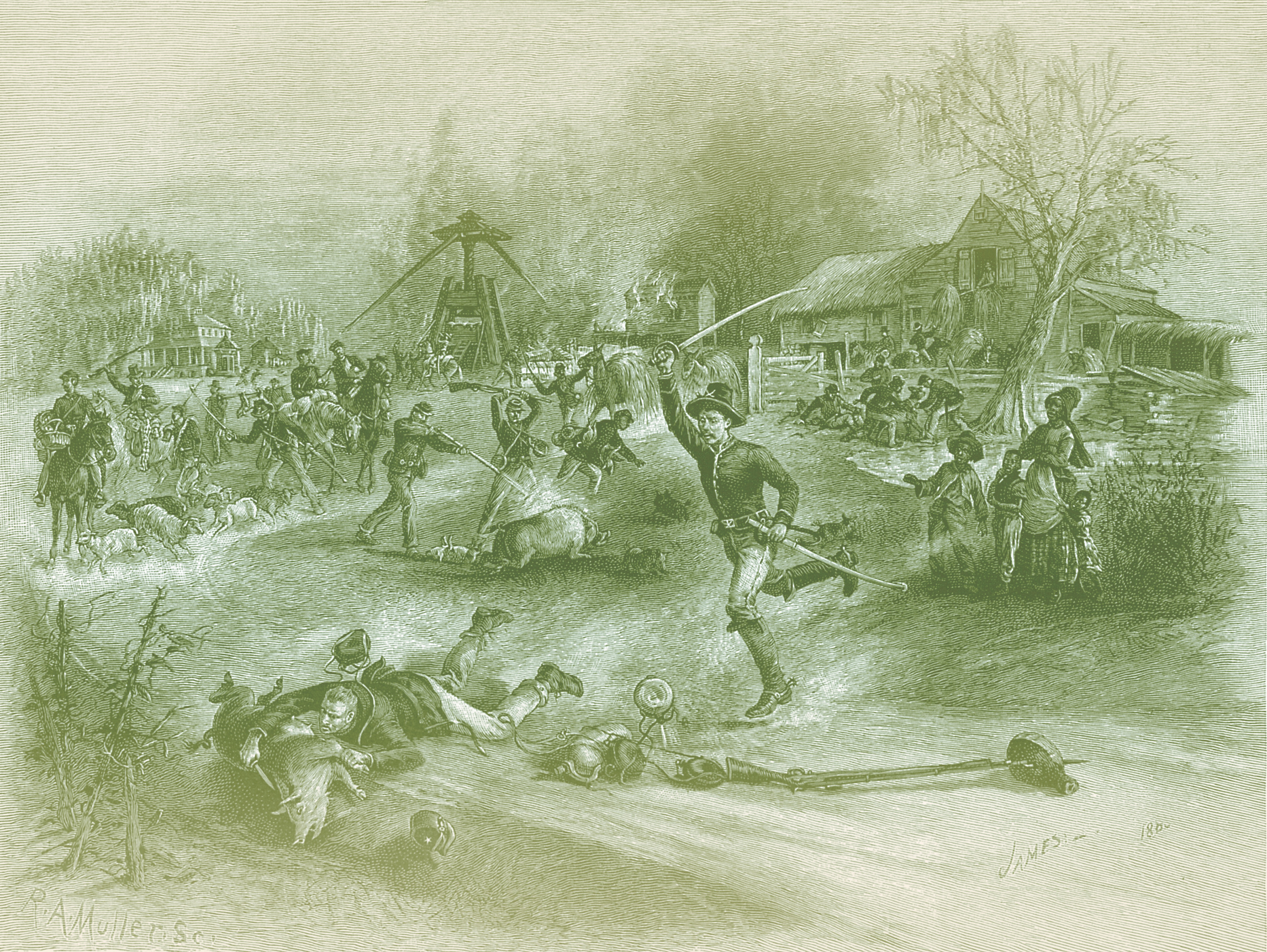

The 1st Alabama often spearheaded Maj. Gen. Francis P. Blair Jr.’s column of the march. A common refrain of Blair’s orders placed “the First Alabama Cavalry…moving in advance,” and the regiment consistently led the 17th Corps en route to Savannah. Making up the vanguard, the 1st most often received orders to secure towns, ferries, bridges, and railroads in advance of the main host. The men often seemed to take special glee in the destruction and seizure of Confederate property. Given license to vent their frustration toward their late countrymen, they sometimes overindulged their desire for retribution.

The conduct of Spencer’s men even earned the colonel an official sanction. “The major-General commanding directs me to say to you,” read the reprimand, “that the outrages committed by your command during the march are becoming so common, and are of such an aggravated nature, that they call for some severe and instant mode of correction. Unless the pillaging of houses and wanton destruction of property by your regiment ceases at once, he will place every officer in it under arrest, and recommend them to the department commander for dishonorable dismissal from the service.” The 1st became notorious on the March to the Sea, writes historian Joseph T. Glatthaar, because they “felt they had a right to retaliate for the way pro-Confederate southerners had pillaged their family homes, imprisoned family members, and drove them from their communities.”

For Lieutenant David R. Snelling, commander of Company I, the campaign represented something of a homecoming. Employed as a colporteur in central Georgia before the war, Snelling “knew every stream and cross-roads, and kept by the side of ‘Uncle Billy’ all the way, to post the old man.” In his youth, Snelling’s uncle had forced him to work in the fields side-by-side with his slaves, engendering a deep hatred for both planters and slavery in the young man that resulted in a dedicated Unionism. Faced with conscription in 1862, Snelling, like a number of his comrades, had initially entered the Confederate Army before deserting and joining Union forces that summer. Enlisting as a private, he rose to the rank of lieutenant.

On the March to the Sea, in Baldwin County near Milledgeville, he took his opportunity for revenge, and went out of his way to lead a raid against his uncle’s plantation. Sherman later recalled the episode in his memoirs:

Lieutenant Snelling, who commanded my escort, was a Georgian, and recognized [an] old negro, a favorite slave of his uncle, who resided about six miles off; but the old slave did not at first recognize his young master in our uniform…his attention was then drawn to Snelling’s face, when he fell on his knees and thanked God that he had found his young master alive and along with the Yankees. Snelling inquired all about his uncle and the family, [and] asked my permission to go and pay his uncle a visit, which I granted, of course.

Leading a detail to the site of his prewar suffering, Snelling had his men make off with as many provisions as they could carry and pointedly destroyed the cotton gin. “The uncle,” wrote Sherman, “was not cordial, by any means, to find his nephew in the ranks of the host that was desolating the land.”

In the end, Sherman did not punish the 1st for its seemingly vindictive destruction. In general, it fit his policy. “The fact is,” writes historian Terry L. Seip, “Spencer and his men were pretty much doing what Sherman wanted done, he knew Spencer and the Alabamians were capable of doing it, and the regiment remained in the vanguard.”

Leading the line could carry risks, however. On December 8, as the regiment approached Savannah, a “torpedo”—or mine—exploded in its path, leaving Lieutenant Francis W. Tupper’s horse dead and his leg “blown to pieces.” Tupper survived the wound, but lost his leg. Sherman arrived on the scene quickly, where he ascertained that “a torpedo trodden on by [Tupper’s] horse had exploded, killing the horse and literally blowing off all the flesh from one of his legs.” Still troubled by the incident when he wrote his memoirs, Sherman declared: “[T]his was not war, but murder, and it made me very angry.” Sherman then ordered forward a group of Confederate prisoners whom he forced to act as minesweepers, “so as to explode their own torpedoes, or to discover and dig them up. They begged hard, but I reiterated the order, and could hardly help laughing at their stepping so gingerly along the road.”

This one incident notwithstanding, the 1st Alabama faced only sporadic opposition and relatively little danger on the March to the Sea. Confederate Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Ferguson, who believed he had destroyed the “Tory regiment” in October 1863, led some of the cavalrymen who feebly harassed the Union forces, but by the winter of 1864 the tables had turned. Confederate resistance proved ineffectual and made little dent in the men’s morale. After securing the surrender of Savannah around Christmastime, Colonel Spencer wrote to General Dodge, now commanding the Department of Missouri in St. Louis, informing him that, “we have had a delightful trip & all enjoyed it.” Without a hint of modesty, he added that he had “done all the fighting that was done by our Column (the 17th Corps) & have made a reputation for both myself & Regiment.” On December 27, when Sherman formally reviewed the troops, Blair placed the 1st Alabama Cavalry at the head of the line—in a hard-earned place of distinction and source of pride for the loyal men of the Deep South.

At the end of the year, a short profile of the regiment circulated in the national press. “Let me say a few words in behalf of the gallant First Alabama,” began a correspondent of the New York Daily Herald, “for it has seldom, if ever, received credit for its valuable services.” The article recounted the unusual regiment’s contributions in the Atlanta Campaign and the March to the Sea when it had “rendered signal service” and praised Colonel Spencer as a “distinguished [and] efficient” commander. “In the ranks of this regiment are to be found some of the original true blue Southern Unionists,” the piece concluded, and “it is needless for me to speak of the intelligence and patriotism of this patriotic body of Alabamians, for their severe denunciation of the rebellion and McClellanism is the best proof of that, but their stainless military record I deemed worthy of more than passing notice. All honor to the 1st Alabama Cavalry, and may their lives be spared to reap the rich reward of their unadulterated loyalty.”

Ultimately, however, the postwar period was fraught with almost as much difficulty for these Yellowhammer State Unionists as their beginning had been. Though they enjoyed a brief ascendancy during the Radical phase of Reconstruction, during which time Colonel (now General) Spencer became Alabama’s first Republican Senator, by the middle of the 1870s Democrats had regained control of state politics and former Unionists once again found themselves relegated to the margins of society. Their failure to form a lasting social and political alliance with African Americans helped pave the way for the “redemption” of the former Confederacy and left them once again on the outside looking in, feeling as though, and treated as though, they had fought on the losing side of the war.

In the latter stages of the 19th century, White Alabama Unionists organized posts of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.), but their adherence to strict segregationist policies increasingly isolated them from the national community of Union veterans. In 1891, the senior vice-commander of Alabama argued that, “such close comradeship as our order inspires, will not permit of the introduction of this element into our ranks…at least here in the South where the question of race enters so largely into the subjects affecting man’s happiness and success.” White Union veterans in the Deep South showed themselves willing to wear the same uniform in war but not in peace. As they organized to commemorate their service, Alabama’s Union veterans felt no obligation to defend the civil rights of their African-American former comrades against their mutual former foe. This did not sit well with many G.A.R. members outside the former Confederacy, who insisted that (at least de jure) equal legal status before the law had constituted one of the principles enshrined by Union victory.

Unwilling to embrace their black fellow-Union veterans, shunned by both their unrepentant and rehabilitated former Confederate neighbors, White Unionists throughout the Deep South began to fade out of Civil War memory. Today, little visible evidence remains of the obstinate White Unionism that existed in the heart of the Confederacy, and they are little remembered. Yet White Southerners also had a part to play. Some even marched with Sherman through Georgia, and they ought not to be forgotten.

Clayton J. Butler is a postdoctoral scholar at the Nau Center for Civil War History and earned his Ph.D. from the University of Virginia in 2020. He is currently at work on his first book, which is under contract with Louisiana State University Press.