The heroism of a small band of British soldiers in northern France is remembered worldwide more than 80 years after they were murdered by Waffen SS troops in what is known as the Wormhoudt Massacre. On May 28, 1940, about 100 soldiers from the 2nd Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment, the Cheshire Regiment and the Royal Artillery were locked in a small barn and killed after managing to defend the area around the town of Wormhoudt for no less than five hours.

The men made a courageous last stand. Not unlike the legendary 300 Spartans at Thermopylae, the small group successfully beat back an onslaught of German troops to allow British forces to escape from Dunkirk.

“It wasn’t so much a meeting engagement as it was a planned defensive position by the British to hold that route point for as long as possible,” Lt. Col. Keith Kiddie (Ret.) of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers told Military History in an interview. “People always know about the retreat to Dunkirk and the fighting on the beachhead, and how they got the Army off the beaches—everybody knows that story,” he said. “But nobody knows the bits of that story that came together to make it happen.”

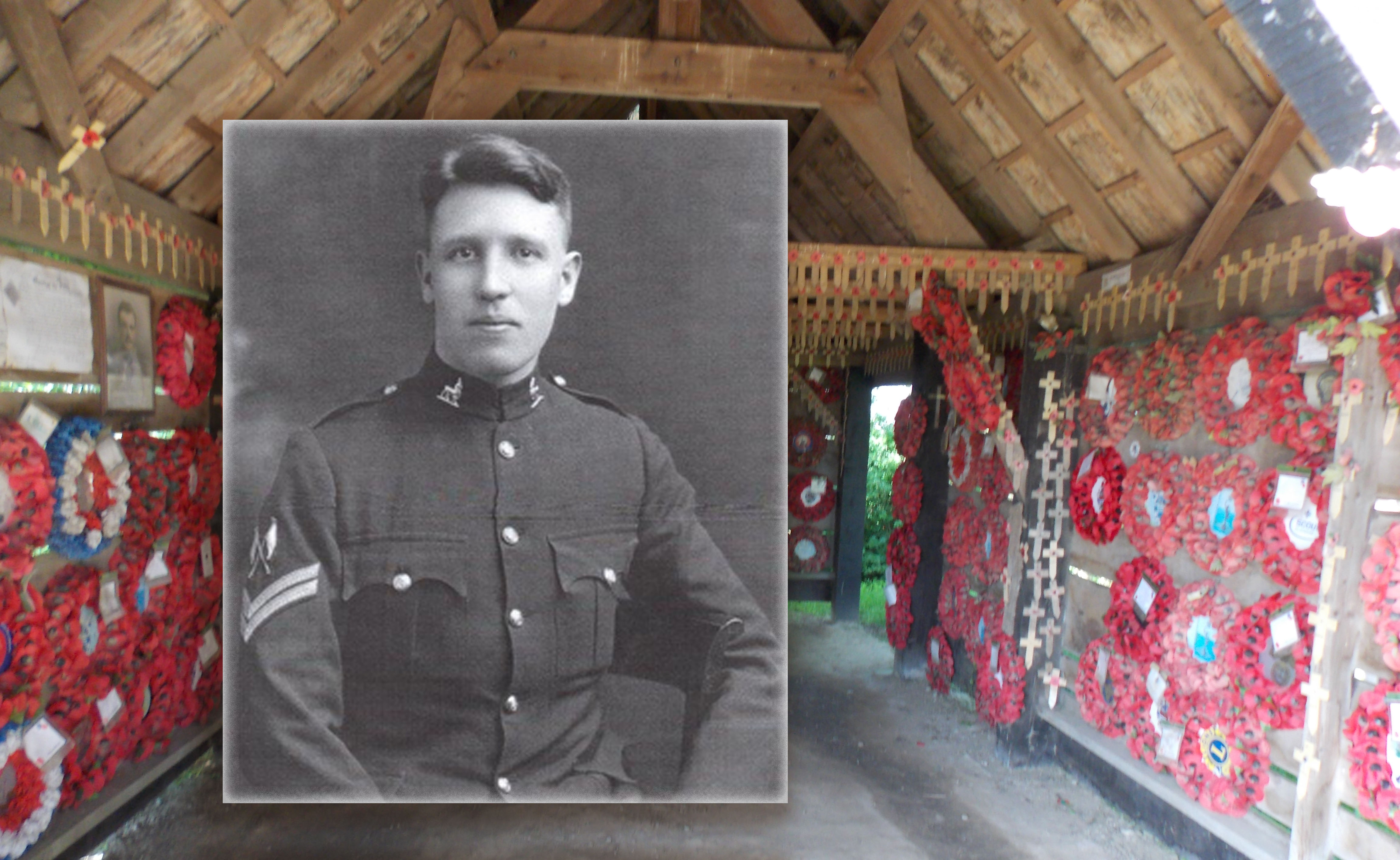

Kiddie helps organize visits on behalf of the Fusiliers Association to the former massacre site, which today holds a shrine and memorial with trees planted in memory of the fallen. The shrine stands on the site of the barn where the British soldiers were killed by the Waffen SS. The walls inside are covered with poppy wreaths and tributes to the deceased.

At about midnight on May 26 the brave group of soldiers received their orders to defend the Wormhoudt area, according to the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers Museum in Warwickshire, England. The troops had only about one hour of sleep, yet fought magnificently.

“They were hopelessly underequipped. They were virtually out of ammunition before they even started—and yet they managed to hold off the SS for a considerable time,” said Graham Minshull, a former sapper in the Royal Engineers. “They managed to get a lot more people away from the beaches than they would have done if Wormhoudt had fallen.”

The men literally held off the enemy until they spent their last bullets. Winston Churchill’s famous phrase, “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few,” can also be applied to the British rearguard at Wormhoudt, whose actions enabled an estimated 360,000 British and Allied troops to evacuate from Dunkirk.

“It shows the tenacity which the British soldier is renowned for,” said Kiddie. “British soldiers fighting in defensive positions are well known for being very tough to shift.”

Afterwards the men were taken prisoner by the notorious 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler. The Nazi regime favored the Waffen SS for their bestial extremism and propagandized them as “Hitler’s finest troops.”

“First they took all our personal effects—my letter, my photographs of my mum and dad and my two sisters, even the photograph of Elizabeth, my wife,” recalled survivor Albert “Bert” Evans, then 19 years old and a private in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. “The [items] were torn up and burned. They didn’t want any of us identified.”

Plotting murder, the SS troopers marched the group of about 100 men into an isolated area and crowded them into a small cowshed. After ensuring the soldiers were incapable of defending themselves, the Germans threw two grenades into the barn, then opened fire with machine guns. They then shot wounded survivors in the back of the head.

For all their cruelty, the Nazis failed to break the spirit of the British soldiers, who banded together to save their comrades in their final moments.

Company Sergeant Major Augustus Jennings and Sergeant Stanley Moore threw themselves on grenades to protect their brothers-in-arms. Their heroism suppressed the impact of the blasts and contributed to the survival of a handful of men in the barn, including Evans.

In the wake of the explosion, Captain James Lynn-Allen, the most senior officer in the group, saw an opportunity to escape. Instead of fleeing alone, Lynn-Allen valiantly rescued one of his men—Evans, badly stunned and with a mangled arm.

“He could have got away. But he didn’t leave me,” Evans recalled 70 years later.

Lynn-Allen dragged Evans away from the barn in a 200-yard dash to safety. They were cornered by a Waffen SS officer in a pond. The German shot them both at pointblank range.

“And that’s how he died. That’s how my captain died. Saving my life,” Evans remembered. “He was a fine man and a fine soldier.”

Although Lynn-Allen lost his life, he was victorious in his last mission—against all odds, he did succeed in saving Evans. Evans managed to crawl away from the massacre site and was picked up by a German ambulance unit. He survived the war as a POW and passed away in 2013 at age 92.

The heroism of the British against the SS was equaled by a nearby French soldier, Private Robert Vanpee, a local depot guard. Vanpee surrendered to the Germans to save the lives of a French family at a nearby farmhouse who were being threatened at gunpoint. Vanpee was shot and buried in a mass grave with the British soldiers near the barn. The bodies were later recovered and are buried at Esquelbecq Military Cemetery. The inscription on Vanpee’s gravestone reads: “Mort pour la France (He died for France).”

Like most criminals, the Waffen SS troops who perpetrated the murders in and around Wormhoudt refused to admit responsibility for their actions. Survivors and witnesses testified that officer Wilhelm Mohnke was involved in ordering the massacre. Mohnke, who died in 2001, spent his life shirking blame for what happened.

“They always maintained that there was never an order to execute POWs. They always maintained that basically, it never happened,” said Minshull.

The SS hoped to erase these brave men from memory by stripping them of identification and burying them in a concealed spot.

However, the opposite has occurred. The soldiers who defended Wormhoudt live on in the hearts and minds of the many people who remember them today. Local French authorities estimate that thousands of veterans from various countries have visited the shrine at Wormhoudt to honor the courage of the men who gave their lives for others. Additionally, local French residents hold annual remembrance services for the fallen heroes. MH