Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson are unlikely to surrender their spots in the pantheon of Southern war heroes anytime soon. Under their leadership, Southern armies won victories at places like Chancellorsville, Manassas and the Shenandoah Valley that have long fascinated students of military history. But Lee and Jackson are by no means the only Rebels to achieve lasting fame. Some are infamous for defeats suffered under their direction, including Braxton Bragg, John Bell Hood, John C. Pemberton and Gideon Pillow. Others, like P.G.T. Beauregard, Jubal Early, Nathan Bedford Forrest and J.E.B. Stuart, won kudos for their distinctive personalities and storied exploits, while some like James Longstreet, Patrick Cleburne, George Pickett and A.P. Hill owe their renown to fabled engagements such as First Manassas, Chickamauga and, above all, Gettysburg. Yet for all the ink devoted to the conflict’s history over more than 150 years, there remain Confederate commanders who are underappreciated or underrated. Here are 10 whose contributions to the cause of Southern independence merit a second look.

10. Francis Marion Cockrell

Named for the American Revolution’s legendary “Swamp Fox,” Cockrell left his law practice in western Missouri in 1861 to enlist in the Missouri State Guard. He first saw service in the campaigns of 1861-62 that effectively secured Missouri for the Union, and his performance at places like Carthage, Wilson’s Creek and Pea Ridge was reflected in a rise in rank and responsibility. He and his brigade forged a distinguished record during operations around Iuka and Corinth in the fall of 1862 and then participated in the Vicksburg Campaign, where he was wounded. Cockrell was promoted to brigadier general shortly after Vicksburg and participated in the campaign for Atlanta as part of Leonidas Polk’s and Alexander P. Stewart’s corps, as well as the futile effort to take Allatoona. Cockrell was struck three times during the November 1864 fight at Franklin, where his brigade led the assault by Samuel G. French’s Division against Union defenses near the Carter Cotton Gin. More than half the Missouri Brigade fell in that battle. Cockrell recovered in time to lead a division in the unsuccessful defense of Fort Blakely in Alabama in April 1865, where he was captured for the third time. Following the war, he became one of Missouri’s leading politicians, serving for 30 years in the U.S. Senate and for five years on the Interstate Commerce Commission.

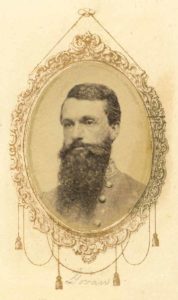

9. John Gregg

Though born in Alabama, Gregg (pictured with a button from his first Rebel unit, the Waco Guards) cast his lot with Texas long before the war, which for him began when the newspaper he was editing championed secession. Elected as a delegate to the Texas secession convention, he became one of the Lone Star State’s representatives to the Provisional Confederate Congress. But he soon resigned his seat and returned home to lead the 7th Texas Infantry. Gregg’s command was among the units forced to surrender at Fort Donelson in February 1862. After being exchanged that August, he became a brigadier general, assigned to the Army of Mississippi. His brigade saw action at Raymond and Jackson during the Vicksburg Campaign, fighting with conspicuous valor at the former, where the general managed to hold up a Union force over three times larger than his own for six hours. Gregg and his command were next assigned to the Army of Tennessee and fought at Chickamauga, where he was severely wounded in the neck during the battle for the Viniard Field on September 19. Returning to the field in time for the start of the 1864 campaign, he next led the Texas Brigade. At the Wilderness, his brigade played a crucial role in turning the tide of the fight along the Orange Plank Road on May 6, though Gregg himself was again wounded. But he remained with his command throughout the Overland Campaign and the opening stages of the Richmond–Petersburg Campaign. On October 7, 1864, Gregg and his brigade were part of the force that Robert E. Lee tasked with driving the Federal cavalry from the Darbytown Road. Gregg’s unit continued pushing south until it ran up against Federals defending the New Market Road—where the general fell mortally wounded in the Army of Northern Virginia’s last offensive north of the James.

a doctor not to amputate his leg. (The Cumberland Press)

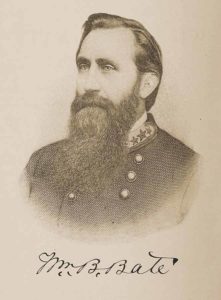

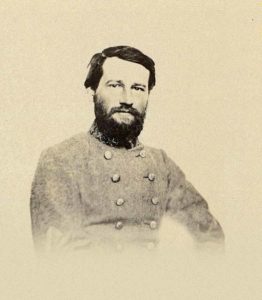

8. William B. Bate

At Shiloh, where William Bate commanded the 2nd Tennessee, he witnessed his brother’s death and also suffered a severe leg wound. Brandishing a pistol, Bate managed to convince a surgeon that amputation was unnecessary—though he would never regain full use of his leg. Despite that, he went on to forge an enviable record, although his strait-laced manner earned him a reputation as a martinet. By the end of 1862, the Mexican War veteran, former newspaper editor and former member of the Tennessee legislature had secured command of a brigade. During the Tullahoma Campaign, his brigade put up a tough fight at Hoover’s Gap but was compelled to fall back with the rest of the Army of Tennessee. At Chickamauga his brigade was in the thick of the fighting, suffering over 50 percent casualties, and at one point on September 19 threatened to break the Union center before coming to grief in Poe Field. Bate was soon elevated to division command. But he complied with misconceived directions about where his force was to be posted, which enabled the Federals to successfully assault his position at Chattanooga. In February 1864, having rejected efforts to convince him to run for governor of Tennessee, Bate was promoted to major general. During the Atlanta Campaign, he saw action at Resaca, New Hope Church, Kennesaw Mountain, Peach Tree Creek, Atlanta and Utoy Creek. He recovered from a leg wound in early August, then resumed command of his division in time to play a prominent role in Hood’s Tennessee Campaign. After participating in the futile assaults at Franklin, Bate and his command found themselves defending Shy’s Hill at Nashville. Though Bate’s performance in that struggle was later criticized, he probably performed about as well as could be expected given the circumstances in which Hood had placed his entire command. Bate made his way to the Carolinas along with other remnants of Hood’s army and, after directing a corps at Bentonville, surrendered with the rest of Joseph Johnston’s command in April 1865. Elected Tennessee’s governor in 1882, he moved over to the U.S. Senate four years later.

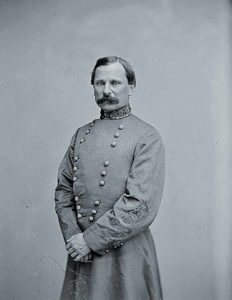

(National Archives)

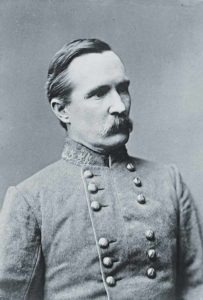

7. Cadmus Wilcox

North Carolina-born, Tennessee-raised Cadmus Wilcox began his service at the head of an Alabama regiment and quickly rose to brigadier general. He led his command with distinction at Williamsburg, Seven Pines, the Seven Days and Second Manassas. Yet despite his impressive record, not to mention the reputation he had established in the antebellum Army as an authority on tactics, when the Chancellorsville Campaign began he was still only a brigade commander—undoubtedly due in part to illness that forced him to miss the Maryland Campaign. Wilcox’s skill as a tactician was on display on May 3, 1863, west of Fredericksburg, when he slowed the advance of a Union force far superior in numbers to his own. The brigadier general’s performance at Chancellorsville was critical to Lee’s ability not only to avoid disaster but also to claim victory. But Wilcox remained a brigade commander when the Army of Northern Virginia marched into Pennsylvania, while officers with less impressive resumés, like George Pickett, commanded divisions. At Gettysburg, Wilcox’s Brigade came close to cracking the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge on July 2, compelling the Union to sacrifice nearly an entire Minnesota regiment to save it. Wilcox subsequently received promotion to major general and command of a division in the Third Corps. Under his leadership, Wilcox’s division remained among the true stalwarts in the Army of Northern Virginia during the brutal campaigns of 1864-65. The fierce defense his men put up of Forts Gregg and Whitworth on April 2 proved critical to the Confederates’ ability to evacuate Petersburg. Wilcox was liked and respected on both sides of the conflict. Both Union and Confederate general officers served as pallbearers at his funeral in 1890.

6. Henry Heth

After a stint commanding Virginia’s Quartermaster Department early in the war, Henry “Harry” Heth turned in solid performances in western Virginia and the Kentucky Campaign. Returning to Virginia in February 1863, he was assigned to A.P. Hill’s Division in the Army of Northern Virginia, but his brigade endured a difficult debut at Chancellorsville in May. Still, he was elevated to division command after Stonewall Jackson and Hill were wounded. Unfortunately for Heth, he is mainly remembered for his performance at Gettysburg, where he was largely responsible for the Confederate army’s troubles on July 1, despite Robert E. Lee’s desire to avoid a general engagement with the Federals. Heth also suffered the indignity of leading his men while wearing a hat stuffed with papers so it would fit—though that likely saved his life when he was struck in the head by a bullet. His injuries, though, meant he had to watch another man lead his men during Pickett’s Charge on July 3. What merits greater appreciation is that Heth was one of Lee’s stalwart leaders during the campaigns of 1864-65. His performance in the fighting south of Petersburg has rarely received its full due. At Globe Tavern, Reams’ Station, Squirrel Level Road and Hatcher’s Run, attacks led by Heth proved crucial in prolonging the fighting until the spring of 1865. After A.P. Hill was mortally wounded on April 2, Lee gave Heth command of the Third Corps. But Heth became separated from the corps during the Union breakthrough that morning, and his men came under Longstreet’s supervision. (Heth later managed to catch up and surrender with Lee at Appomattox.) Today scholars are indebted to Heth for his contributions to the compilation of the Official Records.

5. Daniel C. Govan

While Patrick Cleburne is remembered as one of the few stars of the Army of Tennessee, the same cannot be said of Daniel C. Govan, who helped raise the 2nd Arkansas Infantry in May 1861. Assuming command of the regiment in January 1862, Govan led it through its first engagement at Shiloh even though he was ill at the time. He performed commendably at Perryville, after which Cleburne, his former neighbor, became his division commander. Colonel Govan and his men saw heavy fighting at Stones River, during which Govan temporarily commanded a brigade. In August 1863, he was formally given brigade command, then turned in a stellar performance at Chickamauga and contributed to Cleburne’s defense of Tunnel Hill on November 25, 1863, and led part of the Confederate rear guard two days later at Ringgold Gap. Govan was promoted to brigadier general in December. The following month he bravely endorsed Cleburne’s controversial proposal to bring slaves into the Confederate Army. He led his command through the Atlanta Campaign, seeing action at Resaca, Pickett’s Mill, Kennesaw Mountain, Atlanta and Jonesboro. During the latter engagement, Govan experienced his first real defeat when his command was overrun. He and several hundred of his men were captured. The general was exchanged in September and returned to his brigade in time to participate in Hood’s ill-fated Tennessee Campaign. Govan’s skepticism regarding what would be a doomed assault at Franklin inspired Cleburne’s famous reply, “Well, Govan, if we are to die, let us die like men.” With his command now reduced to fewer than 600 soldiers, Govan and his men still put up a tough fight at Nashville before the general was wounded in the throat. After a brief convalescence, he took his brigade to North Carolina, where he surrendered with Joe Johnston’s army. One of Cleburne’s staff officers called Govan “one of the best soldiers it was my good fortune to know—a true Christian gentleman, a noble patriot.”

4. Stephen D. Lee

Like Heth, Stephen Lee merits a spot on any list of underappreciated Confederates—not least because, like Heth, Lee played a notable role in shaping how the war would be remembered. And few if any of the 17 lieutenant generals in the Confederate Army saw as varied service as Lee, the youngest man to achieve that rank. An 1854 West Point graduate, Lee began the war as a member of P.G.T. Beauregard’s staff at Charleston and participated in negotiations with the Union garrison commander at Fort Sumter preceding the war’s first clash. In 1862 Lee won praise as an artillerist during the Peninsula Campaign and for his service at both Second Manassas and Antietam. Promotion to brigadier general followed shortly after the Maryland Campaign, and by December Lee was commanding an infantry brigade at Vicksburg. At the end of that month, he defeated William T. Sherman’s assaults at Chickasaw Bayou. His conduct in the operations around Vicksburg in following months did little to dim his star, with his performance at Champion Hill (where he was wounded in the shoulder) drawing special notice. After being paroled with the rest of General John Pemberton’s luckless command in July 1863, Lee was rewarded with a much-deserved promotion to major general and appointment to command all the Confederate cavalry forces in Mississippi and Alabama. In May 1864, he was elevated to command of the Department of Mississippi and Alabama and did what he could to manage affairs in that region, turning in a mixed performance. He was promoted to lieutenant general on June 23. In July he received orders to go to Georgia, where he assumed command of a corps in Hood’s army. At Ezra Church and Jonesboro, Lee launched unsuccessful attacks on the Federals. Though his forces suffered casualties that undoubtedly hastened the fall of Atlanta, Lee remained in command throughout the Franklin–Nashville Campaign, during which he was wounded twice. After Johnston’s army surrendered in April 1865, Lee settled in Mississippi. He became a leader in the United Confederate Veterans, also serving as Vicksburg National Military Park’s first superintendent.

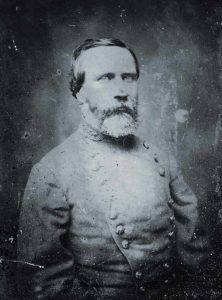

3. Carter Stevenson

Stevenson is one of relatively few Virginians whose legacy is based on fighting mostly outside the Eastern Theater. After serving in the Second and Third Seminole wars and the Mexican War, he was on duty in Utah in 1861 when Virginia seceded, and immediately submitted his resignation from the U.S. Army. Stevenson soon took command of a regiment that saw service in the Shenandoah Valley. In March 1862, he traveled to east Tennessee, where he defended the Cumberland Gap. That September he participated in the campaign in Kentucky that culminated at Perryville, though his command was not part of that battle. A few months later Stevenson was transferred to Vicksburg, where he helped thwart Federal operations in Steele’s Bayou. His command was next tasked with trying to fight off a superior Union force at Champion Hill. The following day he commanded Confederates falling back to Vicksburg after their defeat at the Big Black River. Stevenson surrendered with the rest of Pemberton’s army at Vicksburg. After being paroled, Stevenson returned to the Army of Tennessee and ably commanded a division in the defense of Tunnel Hill at Chattanooga. The Confederate commander’s service during the Atlanta Campaign, especially in the fighting at Resaca, Kennesaw Mountain and Peach Tree Creek, led briefly to his promotion to corps command. At Nashville he once again ascended to corps command and, as at Vicksburg, found himself overseeing a defeated Confederate army’s withdrawal. After leading his division one last time in the Carolinas Campaign, where he saw action at Bentonville, he surrendered with the rest of the Southerners. Stevenson is not remembered for any truly brilliant achievements. But his record as a competent commander in one of the Confederacy’s most important armies merits more appreciation from history.

2. Richard H. Anderson

When friendly fire knocked James Longstreet out of action on May 6, 1864, it was hard to imagine anyone filling his shoes as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia’s heralded First Corps. That responsibility fell on the shoulders of South Carolinian Richard Anderson—who along with Longstreet and Wade Hampton were the only non-Virginians to exercise corps command for any extended period in Robert E. Lee’s army. An 1842 graduate of West Point, Anderson began the war at Charleston Harbor and was wounded for the first time during an engagement in Florida. He received command of a brigade in Longstreet’s Division in early 1862, establishing a solid combat record at Williamsburg, Seven Pines and the Seven Days. He next ascended to division command, playing conspicuous roles at Second Manassas and in the Maryland Campaign, suffering another wound at Antietam and at Chancellorsville. Anderson and his division were then transferred to A.P. Hill’s Corps, and on July 2 participated in the fighting that nearly broke the Union center at Gettysburg. After Anderson succeeded Longstreet as First Corps commander, he reached Laurel Hill before the Federals, which secured Confederate possession of Spotsylvania Court House. Anderson led the corps for the rest of the Overland Campaign, during which he received temporary promotion to lieutenant general. Then Anderson’s command was responsible for keeping the Federals contained north of the James and at Bermuda Hundred. Elements from his force were also sent to the aid of Jubal Early in the Shenandoah Valley. After Longstreet resumed command of the First Corps in October 1864, Anderson led a newly organized Fourth Corps during the final stages of the Petersburg Campaign. Anderson’s military career came to an end after his command was overwhelmed at Marshall’s Crossroads on April 6, 1865. Few officers played as conspicuous a role in the Army of Northern Virginia’s history as Anderson. But while Longstreet, Hill, Stuart, Hood and others are now household names, Anderson remains relatively unknown and unappreciated.

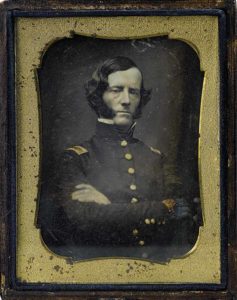

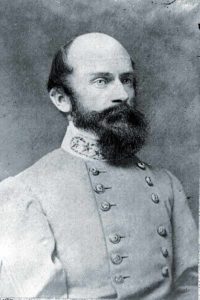

1. Richard S. Ewell

“Old Bald Head’s” appearance on this list might seem unwarranted. Why should a general who figures so prominently in histories of the war in the East and is the subject of an outstanding biography by Donald Pfanz be listed here? In Ewell’s case, it’s because he is underappreciated. Stonewall Jackson would have, of course, cast a huge shadow over whoever succeeded him as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia’s Second Corps. To make matters worse, during Ewell’s convalescence from the gruesome leg wound he suffered at the Brawner Farm in August 1862, he married a cousin whom many found overbearing—inspiring the quip that between Second Manassas and his ascension to corps command, Ewell lost a leg and gained a wife, with both developments being to the detriment of the Confederacy. Add that Lee conspicuously chastised Ewell for losing his temper at Spotsylvania and historian Douglas Southall Freeman titled a chapter on the first day at Gettysburg “Ewell Cannot Reach a Decision,” and you can see why this officer has never received the credit he richly deserves. In 1862 Ewell was crucial to Jackson’s success in the Valley Campaign, playing critical roles at First Winchester and Cross Keys, and fought a textbook delaying action at Kettle Run. Upon promotion to corps command, Ewell demonstrated impressive skill at Second Winchester in June 1863. In 1864 he performed admirably in the Saunders Field fighting at the Wilderness, and at least one modern student insists that Ewell’s success in stopping a Federal offensive that produced Rebel losses at New Market Heights and Fort Harrison made September 30, 1864, the best of Ewell’s many exemplary days of service to the Confederacy. Why has Ewell never been accorded a place in the Confederate pantheon that he deserves? Remember that Lee initially had concerns about Jackson but, once they began working directly together, was able to overlook Stonewall’s eccentricities and appreciate his merits. Ewell never really got that chance. His finest hours came when he was not under Lee’s direct supervision, while Lee was closer at hand for his less-impressive efforts. (That said, were Ewell’s miscues really less forgivable than Jackson’s, for example, at First Kernstown—when he didn’t have the benefit of Ewell’s assistance—or during the Seven Days?) Plus Ewell’s stint as a corps commander came during and after the Gettysburg Campaign, when Confederate fortunes in the East began to decline. Whatever the reason, Ewell was one of the Confederacy’s truly outstanding officers. He deserves far better from history.

Ethan S. Rafuse, who teaches at the U.S. Army Command & General Staff College in Fort Leavenworth, Kan., is the author of Robert E. Lee and the Fall of the Confederacy, 1863–1865.