The Japanese cracked every American combat code until an elite team of Marines joined the fight. One veteran tells the story of creating the Navajo code and proving its worth on Guadalcanal.

JULY–SEPTEMBER 1942

It was our second day at Camp Elliott, near San Diego, our home for the next 13 weeks. The 29 of us followed a Marine officer with a no-nonsense gait into a classroom building. He opened the locked door and marched to the front of the room, standing tall, his uniform spotless, his expression unsmiling, as we piled in behind him.

Two months ago, we had been among 200 young Navajo men recruited by the Marines to apply for a top-secret project. We were the ones who had been selected, and over the last seven weeks we completed basic training. But the nature of our mission remained a mystery. Several men guessed we’d be assigned desk work. After all, the selection process had involved our language skills with English and Navajo. Some thought we’d join the actual fight overseas, a chance to prove our courage.

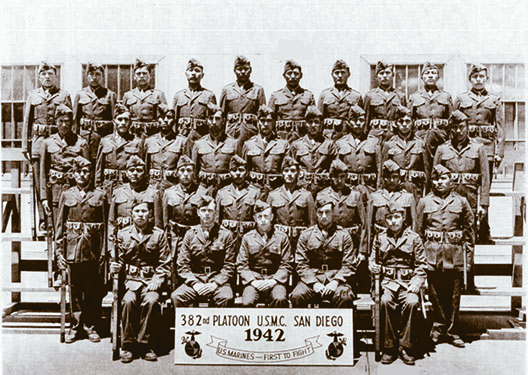

The officer wasted no time. He looked around the room at each of us, the carefully selected Marine recruits of Platoon 382, and told us we were to use our native language to devise an unbreakable code. I read expressions of shock on every face. A code based on the Navajo language? After we’d been so severely punished as children for speaking it at boarding school?

“For starters, you’ll need a word for each letter of the alphabet,” the officer told us. He locked the door as he left, telling us we’d be released at the end of the day to get dinner.

Hearing that door lock click closed, I again felt my stomach tense. The windows of our classroom were protected by security bars. Now what?

After some discussion, we began to see the wisdom in our assignment. Navajo is a very complex language. And since it was not written, the Japanese could learn it only from a Navajo or from one of the rare non-Navajos who had lived on the reservation and learned to speak the language. To be honest, I don’t think they could have learned the language even then. It was just too complicated.

Navajo bears little resemblance to English. When a Navajo asks whether you speak his language, he uses these words: “Do you hear Navajo?” Words must be heard before they can be spoken. Many of the sounds in Navajo are impossible for the unpracticed ear to distinguish. The words for “medicine” and “mouth” are pronounced in the same way, but they are differentiated by tone. There are also fine shades of meaning. If one dumps coal from a bucket, for instance, the verb is different from the verb used to describe dumping water from a pail. And the verb again differs when one dumps something from a sack. Pronunciation, too, is complex. English can be spoken sloppily and still be understood. Not so with the Navajo language. So even though our task made us nervous, we realized that we brought the right skills to the job.

Still, how could we develop a code robust enough to be used in battle? A code responsible for sending life-or-death messages? Where to begin?

We stared at the locked door of the room in which we sat. One of our men, Gene Crawford, had been in the reserves and had worked with codes before. There were certain things that were important. The code words must be clear when spoken on the radio. Each word must be distinct from the other words in order to avoid confusion. The officer who’d locked the room was correct: a good way to begin was to select a word to represent each letter of the alphabet.

On that first day, we decided to use an English word to represent each letter of the English alphabet. Those words would then be translated into Navajo, and the Navajo word would represent the English letter, creating a double encryption. “A” became “red ant”—not the English word for ant, but the Navajo word, pronounced wol-la-chee. “B” became “bear,” pronounced shush in Navajo. “C” was “cat,” or moasi.

There was no dissension among us in that locked room. We focused. We worked as one. This was a talent long employed in Navajo culture—many working together to herd the sheep, plant the corn, bring in the harvest. Day one ended, and the fledgling code had already begun to take shape. We 29 Marines had come up with a workable structure. We slapped each other on the back, and joked to let off steam, feeling good about our work. The impossible-seeming task suddenly looked possible. We would not let our country or our fellow Marines down.

It was Saturday, 3:30 in the afternoon, after a long week of code work. It had taken us about five days for us to devise Navajo word equivalents for the full alphabet. The most difficult letters were J and Z. We finally settled on “jackass,” code word tkele-cho-gi, and “zinc,” code word besh-do-tliz.

My buddy Roy Begay sat on his bunk in the barracks, his blanket pulled tight like a drum, military style. He grinned at me as I sprawled on the adjacent bunk.

“Spell ‘beer,’” Roy said.

I chuckled, and replied “Shush dzeh dzeh gah.”

“Good,” Roy said. A smile lit up his face.“Let’s find the other guys and get some shush dzeh dzeh gah. Now.”

We often wound up at a favorite watering hole, a sort of enlisted men’s club on base we called The Slop Chute. There they served food in addition to alcohol, so we could have a meal and a drink or two without getting sloppy.

When we left base and ventured into San Diego, we arrived at bars wearing our Marine uniforms and were served with no questions asked. Out of uniform, Indians would not be served alcohol. The popular idea was that a drunk Indian was a bad Indian. That was just the way it was.

On weekends, my group had to be back at barracks by around 7:30. We took our new job seriously and always returned on time, and we never got so drunk that we had to be brought to the base by other Marines. Every night we quizzed each other on the code, spelling messages until we knew the Navajo code words for the English alphabet without a flaw. We knew that the strength of the group made us all sharp. And in combat, the code would only be as strong as the teams using it to send and receive.

Fortunately, memorization was second nature for us. Despite the efforts of boarding schools to repress it, Navajo oral tradition remained strong. Stories were still told around the campfires at home, memorized, and told again and again. From the time of their birth, Navajo children were exposed to the exacting and complex thought processes required by the Navajo language. It certainly contributed to the abilities required to be a code talker: learning quickly, memorizing, and working under extreme pressure. In the heat of battle, not one of us could afford to be rattled. We studied till we were exhausted, then studied some more.

After finishing the alphabet code we devised nearly 220 terms for various concepts and diverse types of military equipment. We men, barely off the reservation, were not familiar with military terms. We asked for three Navajo-speaking military men to help us. Felix Yazzie, Ross Haskie, and Wilson Price were pulled from their Marine duties and assigned to help us with the code. After we developed the code together, they went into battle with us. I don’t know why historians insist on separating them from the original 29. For me, it was the original 32.

In Navajo, no equivalent for words like “fighter plane” existed. So we talked about how animals lived and hunted, and did our best to link them up logically with a piece of military equipment. “Fighter plane” was represented by the quick and maneuverable hummingbird, da-he-tih-hi. The huge transport planes were represented as an eagle who carried prey, atsah. Sometimes we used non-animal items to represent certain things. A hand grenade was a potato, or nimasi. Bombs were eggs, a-ye-shi. Japan was “slant-eye,” beh-na-ali-tsosie. The code name chosen to represent the United States of America: Ne-he-mah, “our mother.”

By the end of the development phase, we felt sure we had a code that even a native Navajo speaker would not be able to crack. Our classroom was unlocked, and we code talkers went out on maneuvers to test the code and to practice, practice, practice. When we saw the letter C we had to think moasi. In battle, there would be no time to think: “C, cat. That’s moasi.” It had to be automatic, without a conscious thought process. We became living code machines.

Finally, after 13 weeks of developing our code and demonstrating its speed and accuracy to various high-ranking officers, the Marine brass threw their considerable weight behind us. We had earned staunch allies. The Japanese, we were informed, had a well-earned confidence that they could decipher any code devised by the United States. But they were unaware that a new era of wartime communications had begun.

NOVEMBER 1942

Roy Begay and I, now a radio team, had made it to the Guadalcanal beach alive, wading to shore among floating bodies. We’d dug our first combat foxhole and now sat in it, soggy and scared. If the enemy attacked that night, Roy and I had our equipment ready. Each of us had been issued three hand grenades, a small packet of bullets, dextrose and salt tablets, sulfa (the precursor of penicillin) in case we got shot, a field dressing, and K rations. Ironically enough, one of our staples was a bar of Fels-Naptha, the same brown laundry soap we’d had our teeth brushed with as punishment for speaking Navajo in boarding school.

Some communications officers on Guadalcanal greeted us Navajos with skepticism. Yes, they’d been given notice about the arriving code talkers. And yes, the old Shackle coding system was slow. It used a machine to encode a written message. The encoded message was then sent via voice. These encoded messages were a jumble of numbers and letters, and unlike the Navajo code, were meaningless to the person transmitting them. At the receiving end, a cipher was used to decode the message. The entire process was cumbersome and prone to error.

Yet the notion of changing to something new during the heat of conflict filled battle-weary minds with doubt. My group of code talkers was assigned to just such a doubter in the 1st Marine Division: Lieutenant Sanford B. Hunt, signal officer under General Alexander Vandergrift. When we Navajos assigned to him had arrived, Hunt just shook his head. He knew of our mission, but he had never worked with a group of Indians, and he had faith in the old code.

He had decided to test the new code immediately, and gave us a message to send out on our first night. But directly after the transmission began, panicked calls came in. Hunt’s other radio operators jammed our message, thinking the Japanese had broken into their frequency. By then it was dark, and Hunt postponed the test.

That next morning Hunt continued with the trial, ordering his radiomen not to jam the transmissions. Both the code talkers and the standard communications men were given the same message, one Hunt estimated would take four hours to transmit and receive using the old Shackle protocol.

While the men utilizing the Shackle code waited for the encoding machine to accomplish its work, one of our men transmitted the message to another code talker—in two and a half minutes. And the message was transmitted accurately, word for word. Lieutenant Hunt was impressed. But we Navajo code talkers already knew our code was good. With a code that could keep military plans and movements secret, our country would outmaneuver the Japanese. We were sure of it.

Even after Hunt’s test, American fighting men who overheard the Navajo messages continued to be alarmed. To identify ourselves as U.S. troops, and to keep our transmissions from being jammed, we initiated our messages with the words “New Mexico” or “Arizona,” followed by the date and time in Navajo. We finished off with the time and date again, then with either “gah, ne-ahs-jah,” the letters R and O, standing for “roger and out” or simply “ne-ahs-jah.”

None of us liked to think about it, but we had also planned a strategy in case we got captured. If the Japanese ever forced a code talker to send a message, he would alert the person on the receiving end by embedding in the message the Navajo words for “do or die.”

That first full day on Guadalcanal, after we passed Lieutenant Hunt’s test, runners began arriving with messages involving combat details to be sent to communications personnel, to the front lines, and to the rear echelon. Roy and I grabbed the radio, the size of a 30-pound shoebox. It stored up electricity generated with a turn-crank. Both of us wore headphones so we could hear each other. Thin red and yellow cords attached the microphone and headsets to the radio. There was a button for transmitting and one for receiving. We moved to a position close to a Japanese nest of 80mm machine guns. A continuous barrage of shells from those Japanese guns wrought heavy damage on our men.

A runner approached, handing me a message written in English. It was my first battlefield transmission in Navajo code. I’ll never forget it. Roy pressed the transmit button on the radio, and I positioned my microphone to repeat the information in our code. I talked while Roy cranked. Later, we would change positions.

“Beh-na-ali-tsosie a-knah-as-donih ah-toh nish-na-jih-goh dah-di-kad ah-deel-tahi.” Enemy machine-gun nest on your right flank. Destroy. Suddenly, just after my message was received, the Japanese guns exploded, destroyed by American artillery. I shouted, “You see that?”

“Sure did,” Roy grinned, but didn’t stop cranking the radio.

“U.S. artillery nailed them,” I said. As I viewed this small victory—a direct result of my transmission—the wet, the fear, the danger, all receded for a few seconds.

Roy and I ran and crawled to a new position, knowing the Japanese were experts at targeting the locations from which messages had been sent. The enemy picked up U.S. radio signals and delivered mortar shells to those locations. We never stayed on the radio a second longer than we had to. And the frequencies we used changed every day.

Immediately we focused on sending the next message, moving, then sending the next. Bullets zipping around us kept the level of noise high but that didn’t keep us from hearing incoming messages. Luckily both the headsets and our ears were good, and we heard the Navajo words in spite of the war exploding around us.

Occasionally, I looked over at Roy, who tirelessly carried and cranked the radio. He nodded, still cranking. After a couple of hours, we switched positions. I cranked and Roy spoke. My head reeled with Navajo and English words, with coordinates, with messages sent. It was good just to crank for a while, good not to worry about slipping, making a mistake that could cost lives.

Artillery shells whistled past us. I dived, the radio under me. Roy lay flat out on the ground. We never stopped transmitting.

More than 24 hours passed before we were able to grab a few hours of sleep. We woke, still exhausted, in the hole we’d dug two days before. Snaking our way to the mess tent on all fours, we ducked bullets and artillery shells. At the mess we grabbed some cold food and ate ravenously.

“Not like the hot food in boot camp,” I said.

“Heck, no. That food was good,” Roy said around a mouthful of cold Spam. I shoveled a forkful of cold eggs into my mouth and swallowed. “Not too bad.”

We returned to relaying messages. My throat grew raw with talk. Never before had I spoken so many words without a break. We tried to ignore cramped muscles, gnawing stomachs, and the ordnance exploding around us.

Our messages relayed calls for ammunition, food, and medical equipment back to the supply ships waiting offshore. Messages transmitted the locations of enemy troops to U.S. artillerymen. Messages told of something unexpected that had happened in battle. Messages reported on our own troop movements. Messages forwarded casualty numbers, the Navajo code keeping the Japanese from learning of American losses in each foray. Throughout the days of battle to come, we sent those numbers back to our commanders on the ships each night.

After being in operation for just 48 hours, our secret language was becoming indispensable.

The hilly terrain on Guadalcanal posed real problems for the men operating mortars and artillery. The men firing all of these weapons dealt with a serious issue. Marksmen had to clear the hills—and the heads of our own troops—while drawing an accurate bead on the enemy. This became especially ticklish when our weapons were shooting behind the enemy and drawing them closer to the American troops at the front line. As they drew closer, we continued to fire behind them, moving both our fire and the Japanese troops closer and closer to our own troops.

There was no room for error in a maneuver like that. Often, in the midst of battle, the Marines transmitted in English instead of using the Shackle code. They knew the transmissions were probably being monitored by the Japanese, so they salted the messages liberally with profanity, hoping to confuse the enemy.

We code talkers changed all that.

Roy and I traveled close to the mortars. Sweat streamed down my back. I transmitted coordinates detailing the locations of Japanese and American troops. I knew men’s lives depended upon the accuracy of each word. I wiped my brow with a sleeve but never stopped talking. Out of the corner of one eye, I saw a flash of fire. Sand and shrapnel kicked up into the heavy gray sky. I kept talking.

Just then a spotter returned from locating a pocket of Japanese soldiers and artillery. Someone handed a slip of paper to me, bearing the exact Japanese location. The same note also reported the location of forward U.S. troops.

I squinted, rubbed my eyes, read the paper again. Any error could cause the death of my fellow fighting men. I’d sent hundreds of messages. Messages swam in my brain, jamming and tumbling over one another. I shook my head to clear it.

I translated the data into Navajo code and spoke into the microphone that fit neatly into my fist like a baseball. I spoke clearly, carefully. I imagined those men planning a trajectory, one that would fire over the heads of the Americans and hit the Japanese. If a soldier was shot right beside us, we had been warned not to stop and help. Our transmissions could not be interrupted.

Another spotter arrived. He ducked down next to me to hand me a message. “Fighter pilots,” he said.

American planes were scheduled to drop bombs ahead of the American line. The message I held gave the coordinates of forward U.S. troop locations on the island. Before we code talkers arrived, some of the pilots had dropped their bombs as soon as they reached the island, hitting U.S. troops with friendly fire, then reversing course and flying back to their carrier. I’d heard how the brass got all over the pilots’ butts when they almost bombed my 1st Marine Division. Now we code talkers were utilized, relaying coordinates that would be forwarded to the pilots, making sure that they knew the locations of their own troops.

The runner took off, crouching low to avoid enemy fire. Exhausted, I took a sip of water from my canteen and translated the information into code. I relayed it to an aircraft carrier sitting offshore. As I finished, another runner arrived with another message to be sent.

DECEMBER 1942

Official word had come. Relief. Major General Alexander Patch was ordered to take command of the Guadalcanal effort.

Roy and I prepared to leave Guadalcanal along with the rest of the 1st Marine Division. But at the last minute, a lieutenant pulled 10 of us code talkers aside, Roy and me among them.

“Men, you’ve done an excellent job.” He stopped, cleared his throat. “I’m afraid we can’t afford to let you go. You are vital to the success of this campaign. The 2nd Marine Division still needs you men here.”

Heavy silence settled over us. I looked across the beach, littered with broken and worn-out equipment of war. I felt just as worn out as those useless vehicles and broken-up gun emplacements. But a used code talker couldn’t be replaced by a new model off the factory floor. And there were too few of us to expect replacements the way other infantrymen could expect them. It was a crushing disappointment not to be leaving with the rest of our division. We’d made good friends on the battlefield, where everyone depends on his buddies.

We got ourselves squared away. We resolved to keep fighting. On December 9, we watched as the other Marines from the 1st Division boarded transports for Australia. We code talkers waved goodbye to our friends—some of whom were best buddies—and tried to prepare ourselves mentally to forge new bonds as the war continued. ✯