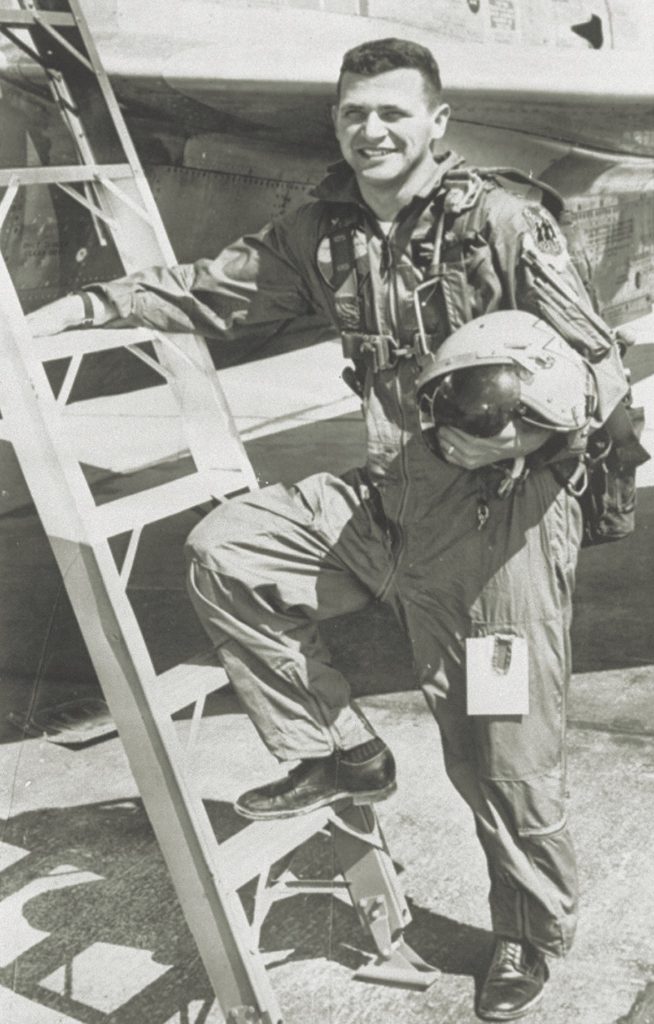

Thirteen miles above the Ural Mountains, an orange flash lit the sky one spring morning in 1960. A Soviet anti-aircraft missile had found its target, an aircraft that began tumbling wildly. Both wings blew off. The pilot, Francis Gary Powers, managed to eject and open his parachute. Powers was on one of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency’s most secret missions. He was flying the U-2, a plane that almost no one knew existed. Floating down, he later wrote, he imagined the “tortures and unknown horrors” that might await him in captivity. Fortunately, Powers had a way out. Around his neck, like a good luck charm, hung a silver dollar he had been given. Hidden inside was a pin coated with poison. The coin was a gift from Sidney Gottlieb and friends.

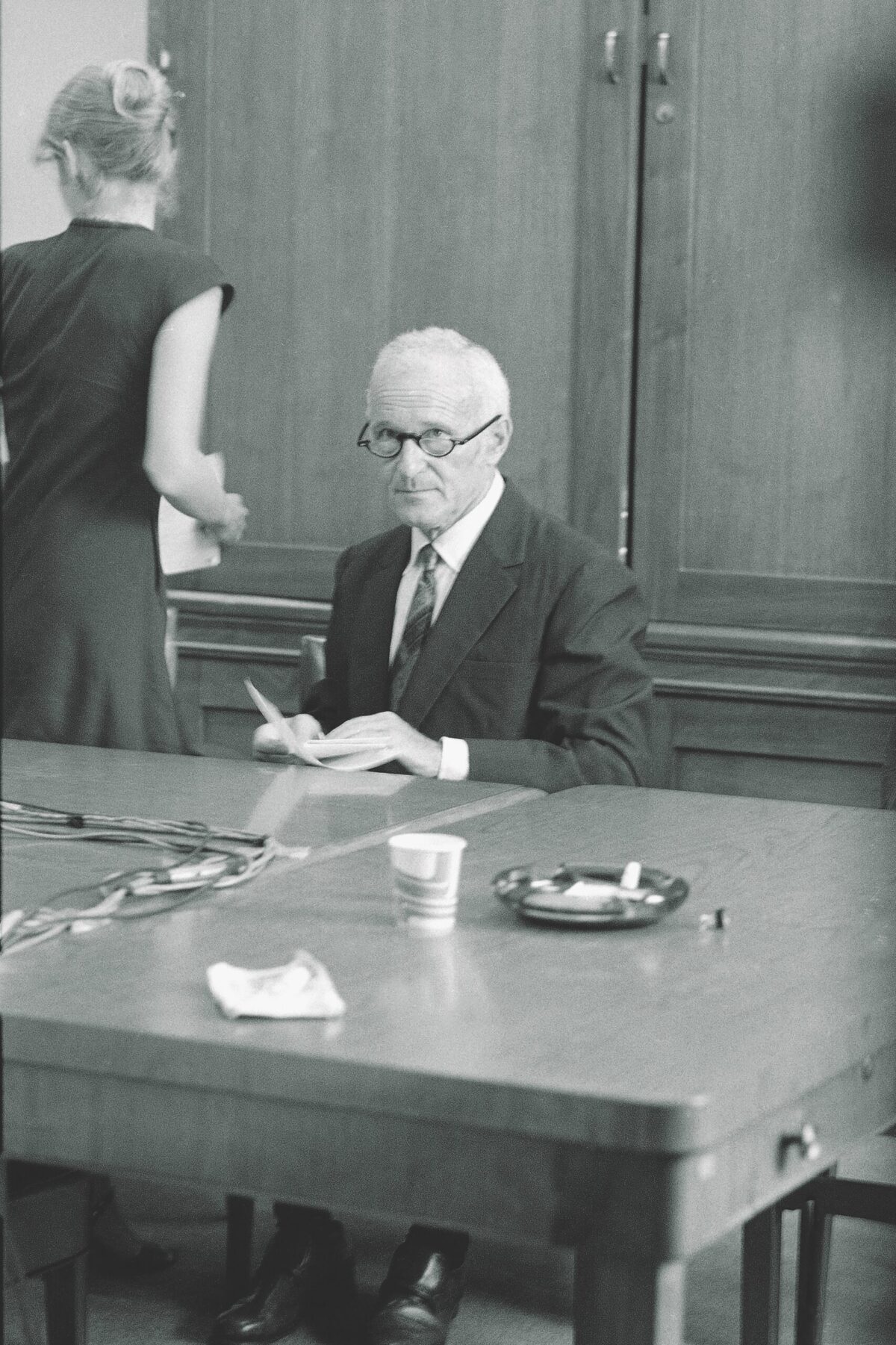

Gottlieb, 43, was a biochemist. A son of immigrant Jews, he had been born with club feet. He spent his childhood in the Bronx wearing leg braces. He stuttered. But he was smart and ambitious, with a gift for science. He obtained a Ph.D. at California Institute of Technology in 1943. The Selective Service ranked him 4F, but he found work doing research at federal agencies and universities in the Washington, DC, area. He lived in a log cabin with his wife and their four children on 15 wooded acres near Vienna, Virginia. Hired by the CIA in 1951, Gottlieb had worked on Special Operations Division projects at Camp Detrick, near Frederick, Maryland. This evolved into MK-ULTRA, a program Gottlieb headed starting in 1953. His shop’s main mission was developing mind control tools—one study focused on adapting the hallucinogen lysergic acid diethylamide-25—LSD—for that use. MK-ULTRA also served other CIA needs, such as making assassination weapons.

In the 1950s, as part of MK-ULTRA, Gottlieb had had agents search the world for natural poisons. Enthralled by new chemicals, he sent promising samples to what had been upgraded to Fort Detrick. Several proved to be deadly.

Gottlieb, now chief of research and development for the Technical Services Staff, had an unmatched knowledge of poisons, which made him the ideal candidate for a delicate assignment. CIA deputy director for plans Richard Bissell, who ran the U-2 project, believed that since his planes would fly at improbably high altitudes, Soviet air defense systems would not be able to shoot them down or even track them by radar. Nonetheless Bissell planned for the worst. The U-2 squadron and its mission—to photograph Soviet military installations—were among America’s most classified secrets. If a plane was lost and its pilot, in Agency jargon a “driver,” fell into enemy hands, much trouble would follow. Bissell asked the Technical Services Staff to provide his pilots with a way to commit suicide if captured.

The chemists reminded Bissell how Nazi war criminal Hermann Goering had slipped a glass ampule filled with liquid potassium cyanide into his mouth, bit down on it, and died within 15 seconds, cheating the hangman at Nuremberg. Bissell ordered six such ampules. Making them was no great challenge. Gottlieb chose a poison, and a Special Operations Division officer at Fort Detrick made the ampules. One was handed to the pilot of the first U-2 mission as he prepared to take off from an American base at Wiesbaden, Germany, on June 20, 1956. President Dwight Eisenhower authorized several more flights in the weeks that followed. Each pilot carried one of Gottlieb’s ampules.

On July 5, U-2 “driver” Carmine Vito took off at dawn from Wiesbaden. Vito’s taste for lemon lozenges had led other drivers to call him the Lemon Drop Kid. Aloft, he reached for a lozenge that felt unusually smooth in his mouth and had no taste. Spitting it out, Vito realized he had grabbed his cyanide-filled ampule. He survived only because he had not bitten it. Upon returning, he reported his brush with death. The squadron commander ordered the ampules packed inside small boxes. For four years, U-2 drivers tucked those boxes into their flight suits. There were no more near misses.

Owing to the sensitivity of U-2 flights over the USSR, President Eisenhower insisted on approving each one. Bissell and his boss, CIA director Allen Dulles, assured the president that the planes were practically invulnerable. Even so Eisenhower hesitated to approve a flight scheduled for May 1, 1960. He was to meet Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev at a much-awaited summit in Berlin in two weeks and did not want to risk disrupting it. Finally he gave his approval.

By now, Gottlieb and his partners at Fort Detrick had a suicide tool hidden inside a hollowed silver dollar. Only one was made, since all agreed that if a driver used it, disaster would have struck, and the U-2 program would be history.

That spring, U-2 flights were taking off from a secret CIA airfield near Peshawar, Pakistan. Each driver in turn was given the silver dollar before taking off.

“Inside the dollar was what appeared to be an ordinary straight pin,” Francis Gary Powers later wrote. “But this too wasn’t what it seemed. Looking at it more closely, we could see the body of the pin to be a sheath not fitting quite tightly against the head. Pulling this off, it became a thin needle, only again not an ordinary needle. Toward the end there were grooves. Inside the grooves was a sticky brown substance.”

That substance was a paralytic poison, saxitoxin, extracted from infected shellfish. In a highly concentrated dose, like the one compounded at Fort Detrick, saxitoxin can kill within seconds.

Powers was flying over what is now the Russian city of Yekaterinburg when the exploding missile rocked his plane. Soviet military commanders, frustrated by their inability to stop U-2 overflights, had been steadily improving their air defenses in ways the CIA had not detected. The attack that blew Powers out of the air came so suddenly that he did not have time to hit the button that would destroy the plane’s fuselage. As he fell, his thoughts turned to the suicide pin he was carrying. Drivers were given no clear instructions on how to react if shot down. Powers later testified that the choice of whether to use the suicide pin was left “more or less up to me.” He decided not to.

When CIA air controllers lost contact with Powers’s plane, they presumed he was dead and that his plane had been vaporized. Hurriedly they concocted a cover story: a research plane studying high-altitude weather patterns over Turkey had run into trouble, the pilot had lost consciousness due to lack of oxygen, and the plane had continued on autopilot, lamentably straying deep into Soviet airspace.

“There was absolutely no—N-O, no—deliberate attempt to violate Soviet airspace, and there never has been,” a State Department spokesman told reporters.

he CIA and President Eisenhower presumed the episode would end there. Khrushchev, however, had the last word. In a dramatic speech to the Supreme Soviet a week after the shoot-down, he revealed that large sections of the U-2 had been recovered and that Powers was alive and in custody. Then he held up an enlarged photo of the poison needle.

“To cover up the tracks of the crime, the pilot was told that he must not be taken alive by Soviet authorities,” Khrushchev told his comrades. “For this reason he was supplied with a special needle. He was to have pricked himself with the poisoned needle, with a result of instantaneous death. What barbarism!”

In the most humiliating moment of his presidency, Eisenhower was forced to admit that he had authorized his spokesmen to lie about the U-2. His planned summit with Khrushchev collapsed. Powers was put on trial in Moscow. “If the assignments received by Powers had not been of a criminal nature, his masters would not have supplied him with a lethal pin,” the prosecutor said in his opening statement.

Among the witnesses to appear at the trial was a professor of forensic medicine who had been assigned to evaluate the deadly pin. That testimony constitutes the most detailed analysis of one of Gottlieb’s tools ever made public.

The following was established during the investigation of the pin. It is a straight ordinary-looking pin made of white metal with a head and a sharpened point. It is 27 mm long and 1 mm in diameter. The pin is of an intricate structure: there is a bore inside it extending its entire length except for the sharpened point. A needle is inserted in the bore. The needle is extracted when tightly pulling the pin head. On the sharpened point of the needle are deep oblique furrows completely covered with a layer of thick, sticky, brownish mass.

An experimental dog was given a hypodermic prick with the needle extracted from the pin, in the upper third part of the left hind leg. Within one minute after the prick the dog fell on his side, and a sharp slackening of the respiratory movements of the chest was observed, a cyanosis of the tongue and visible mucous membranes was noted. Within 90 seconds after the prick, breathing ceased entirely. Three minutes after the prick, the heart stopped functioning and death set in. The same needle was inserted under the skin of a white mouse. Within 20 seconds after the prick, death set in from respiratory paralysis . . .

Thus, as a result of the investigation it was established that the substance contained on the needle inside the pin, judging from the nature of its effect on animals, could, according to its toxic doses and physical properties, be included in the curare group, the most powerful and quickest-acting of all known poisons.

In fact, CIA chemist Sidney Gottlieb had gone well beyond curare, a toxin that is found in tropical plants. Saxitoxin, the substance on the poisoned pin, belongs to a class of naturally occurring aquatic poisons that, according to one study, “surpass by many times such known substances as strychnine, curare, a range of fungi toxins, and potassium cyanide.” The lethality of Gottlieb’s suicide pin and the inability of a leading Russian toxicologist to identify the substance with which Gottlieb had tainted it were testimony to the American scientist’s talent.

Powers was exchanged for a Russian spy in 1962. The airman faced a burst of criticism for failing to make use of his suicide pin, but after emotions had cooled Powers was praised for his service. The CIA awarded him a medal. Allen Dulles said the star-crossed pilot had “performed his duty in a very dangerous mission and he performed it well.”

Gottlieb could not be publicly linked to the Powers episode, but it burnished his reputation within the CIA. He was already the CIA’s master chemist. He had, according to one of his colleagues, prepared poison that a compromised CIA officer, James Kronthal, used to commit suicide in 1953. Two years later Gottlieb compounded a dose intended to kill Prime Minister Zhou Enlai of China but not used. By crafting the lethal pin that was given to U-2 drivers, he solidified his position as poisoner in chief.

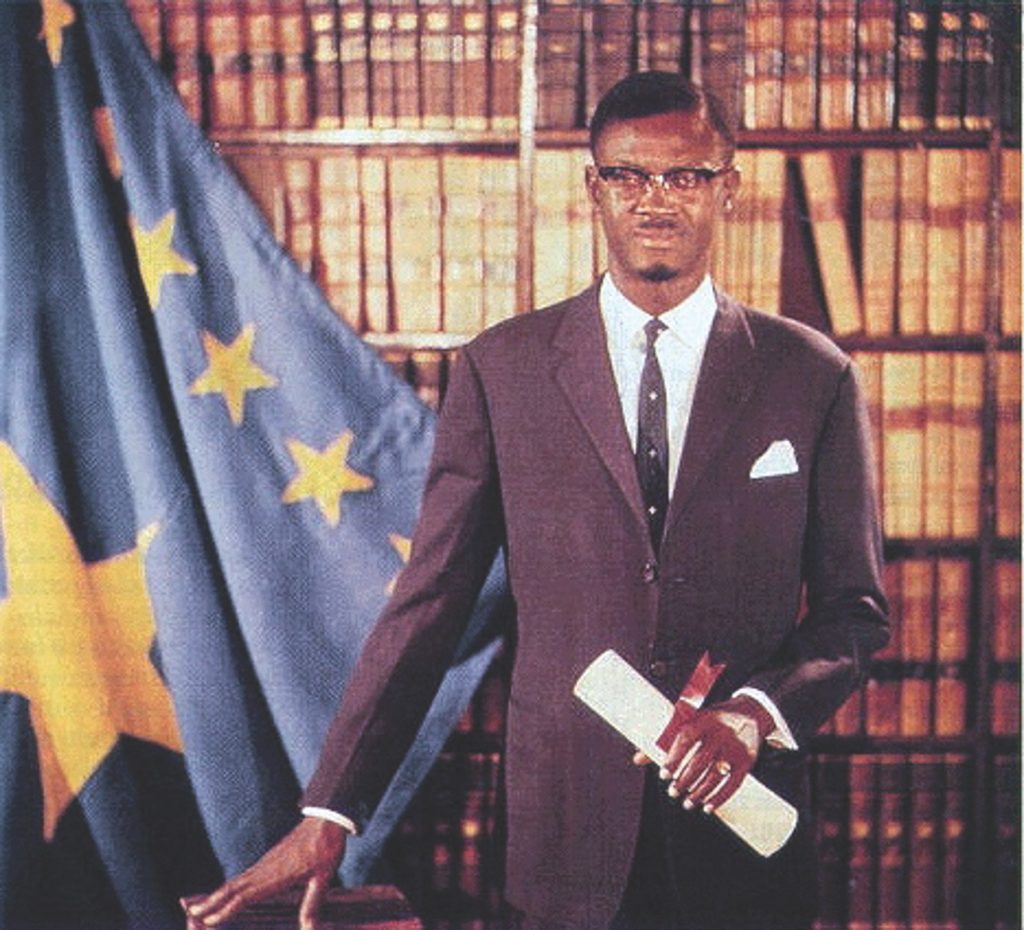

As he walked through the African heat and stepped into an airport taxi, “Joe from Paris” could not avoid reflecting on the war into which he was plunging. The Republic of the Congo, where he had just landed, had won independence from Belgium three months before. The new nation immediately fell into violent chaos. An army mutiny set off riots, secession, and government collapse. The United States and the Soviet Union watched with active interest. A Cold War showdown loomed. Joe from Paris arrived carrying America’s secret weapon.

Larry Devlin, the CIA station chief in Leopoldville, the Congolese capital, was expecting him. A couple of days earlier Devlin had received a cable from Washington telling him that a visitor would soon appear. “Will announce himself as Joe from Paris,” the cable said. “It is urgent you should see [him] soonest possible after he phones you. He will fully identify himself and explain his assignment to you.”

Late on the afternoon of September 26, 1960, Devlin, who had a cover job as a consular officer at the American embassy, left work and headed toward his car. A man rose from his chair at a café across the street. “He was a senior officer, a highly respected chemist, whom I had known for some time,” Devlin wrote later. Joe from Paris was Sidney Gottlieb. Less than five months after the downing of Powers’s U-2, Gottlieb had flown to the Congo on one of the 20th century’s most extraordinary courier missions. With him he carried a one-of-a-kind kit that he himself had designed. It was poison to kill Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba.

Gottlieb approached Devlin and extended his hand. “I’m Joe from Paris,” he said. Devlin invited the visitor into his car. After they had gotten under way, Gottlieb told Devlin, “I’ve come to give you instructions about a highly sensitive operation.”

By the time Gottlieb landed in the Congo, he could look back on almost a full decade at the CIA. He had built MK-ULTRA into the most intense and structured mind control research program in history. Two years in Germany, where he had conducted extreme experiments on subjects considered “expendables,” had strengthened his credentials. The research and development job he was given after his return from Europe made him one of the chief imaginers, builders, and testers of devices used by American intelligence officers. Gottlieb still was running MK-ULTRA. He was also part of an informal group of CIA chemists that became known as the “health alteration committee.” They had come together early in 1960 as a response to President Eisenhower’s renewed conviction that the best way to deal with some unfriendly foreign leaders was to kill them.

At mid-morning on August 18, 1960, CIA director Allen Dulles and deputy director for plans Richard Bissell made an unscheduled visit to the White House. They had just received an urgent cable from Larry Devlin in the Congo. “Embassy and station believe Congo experiencing classic Communist effort takeover government,” Devlin wrote. “Anti-West forces rapidly increasing power Congo and therefore may be little time left.” This cable seemed to confirm deep fears that Prime Minister Lumumba was about to deliver his spectacularly resource-rich country to the Soviets. After reading it, according to the official note taker, Eisenhower turned to Dulles and said “something to the effect that Lumumba should be eliminated.”

“There was stunned silence for about 15 seconds,” the note taker wrote, “and the meeting continued.”

Bissell returned to his office, where he immediately cabled the Leopoldville station asking officers there to propose ways to carry out Eisenhower’s assassination order. They considered using a sniper—“hunting good here when light is right,” one officer wrote—but ruled out that option because Lumumba was living in seclusion and no reliable sniper was available. Poison was the logical alternative.

Gottlieb’s entire career had prepared him for this assignment. He had founded the CIA’s Chemical Division and become the Agency’s pre-eminent expert on toxins and ways of delivering them. As director of MK-ULTRA, he had tested drugs on prisoners, drug addicts, hospital patients, suspected spies, ordinary citizens, and even his own colleagues. He had already compounded lethal poisons. For this uniquely qualified chemist, preparing a dose for Lumumba would be simple.

Bissell told Gottlieb that, pursuant to an order from “the highest authority,” he was to prepare an incapacitating or fatal potion that could be fed to an African leader. He did not name Lumumba. Given that summer’s news, though, Gottlieb could hardly have doubted who the intended target was.

“Gottlieb suggested that biological agents were perfect for the task,” science historian Ed Regis wrote. “They were invisible, untraceable and, if intelligently selected and delivered, not even liable to create a suspicion of foul play. The target would get sick and die exactly as if he’d been attacked by a natural outbreak of an endemic disease. Plenty of lethal or incapacitating germs were out there and available, Gottlieb told Bissell, and they were easily accessible to the CIA. This was entirely acceptable to Bissell.”

Gottlieb began considering which “lethal or incapacitating germs” he would use. His first step was to determine which diseases most commonly caused unexpected death in the Congo: anthrax, smallpox, tuberculosis, and three animal-borne plagues. Gottlieb began looking for a match: Which poison would produce a death most like the one those diseases cause? He settled on botulinum, sometimes found in improperly canned food. Botulinum takes several hours to work but is so potent that a concentrated dose of just two billionths of a gram can kill.

Working with partners at Fort Detrick, where he stored his toxins, Gottlieb began assembling his assassination kit. It contained a vial of liquid botulinum; a hypodermic syringe with an ultra-thin needle; a small jar of chlorine that could be mixed with the botulinum to render it ineffective in an emergency; and “accessory materials,” including protective gloves and a face mask. In mid-September Gottlieb told Bissell that the kit was ready. They agreed that Gottlieb himself should bring it to Leopoldville. He became the only CIA officer known to have carried poison to a foreign country in order to kill that country’s leader.

Less than an hour after Gottlieb and Devlin met in front of the American embassy in Leopoldville, the men were sitting in Devlin’s living room. Gottlieb announced that he was carrying tools intended for the assassination of Prime Minister Lumumba.

“Jesus H. Christ!” Devlin exclaimed. “Who authorized this operation?”

“President Eisenhower,” Gottlieb replied. “I wasn’t there when he approved it, but Dick Bissell said that Eisenhower wanted Lumumba removed.”

The men paused, absorbing the weight of the moment. Devlin later recalled lighting a cigarette and staring at his shoes. After a while Gottlieb broke the silence.

“It’s your responsibility to carry out the operation, yours alone,” he told Devlin. “The details are up to you, but it’s got to be clean—nothing that can be traced back to the U.S. government.” He handed Devlin the poison kit.

“Take this,” Gottlieb said. “With the stuff that’s in there, no one will ever be able to know that Lumumba was assassinated.”

Gottlieb coolly explained to Devlin what was in the poison kit and how to use it. One of Devlin’s agents, he said, should use the hypodermic needle to inject botulinum into something Lumumba would ingest—as Gottlieb later put it, “anything he could get to his mouth, whether it was food or a toothbrush.” Devlin later wrote that the kit also included a pre-poisoned tube of toothpaste. The toxins were designed to kill not immediately, but after a few hours. An autopsy, Gottlieb assured Devlin, would show “normal traces found in people who die of certain diseases.”

Gottlieb remained in Leopoldville. While the chemist waited, Devlin found an agent thought to have access to Lumumba and able, as the station chief wrote in a cable to Washington, to “act as inside man.” Ten days after arriving, Gottlieb felt confident enough to fly home. He left behind, according to a cable from Devlin, “certain items of continuing usefulness.”

The agent Devlin hired proved unable to penetrate the rings of security protecting Lumumba. Devlin knew that the Belgian security service was as determined as the CIA to eliminate the prime minister. Its officers worked closely with the Union Minière du Haut-Katanga, the mining conglomerate that was a cornerstone of Belgian political and economic power. Lumumba fled Leopoldville. On November 29, his enemies captured him. On January 17, 1961, a squad of six Congolese and two Belgian officers took Lumumba out of confinement, brought him to a jungle clearing, shot him, and dissolved his remains in acid.

Of the CIA poison kit, Devlin later wrote that after Gottlieb handed it to him, “my mind was racing. I realized that I could never assassinate Lumumba. It would have been murder . . . My plan was to stall, to delay as long as possible in the hope that Lumumba would either fade away politically as a potential danger or that the Congolese would succeed in taking him prisoner.” Devlin locked the kit in his office safe, where it would lose potency. Gottlieb, however, later testified that he had disposed of the poison before leaving Leopoldville, destroying its “viability,” then dumping it into the Congo River.

The CIA achieved its objective in the Congo unexpectedly and elegantly. Eisenhower had ordered the Agency to kill Lumumba, and he had been killed. Although CIA officers worked closely with the Congolese and Belgians who did the deed, they did not participate in or witness the execution. Nonetheless Gottlieb returned to Washington with a new credential. He had not poisoned the leader of a foreign government, but he had shown once again that he knew how.

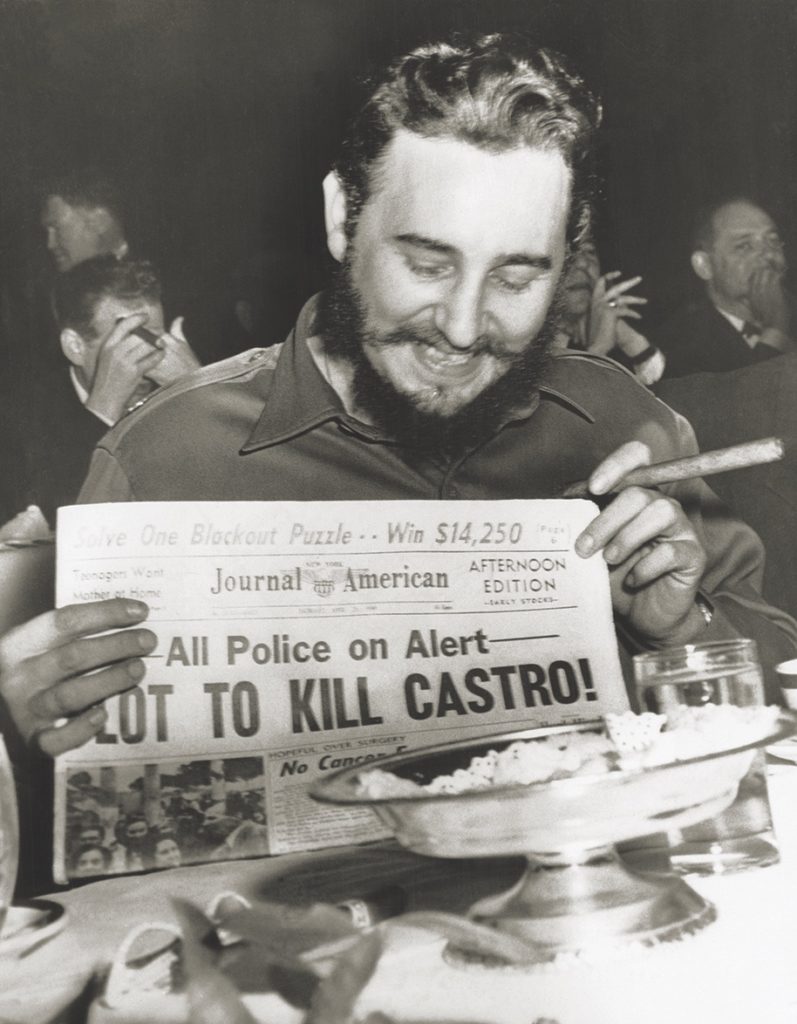

Yes, gangster John “Handsome Johnny” Roselli told an inquiring CIA man, he had associates in Cuba who could kill Fidel Castro. No, Roselli didn’t like the idea of trying to gun Castro down gangland-style or using a sniper. The shooter would almost certainly be killed or captured. Roselli said he would prefer something “nice and clean, without getting into any kind of out-and-out ambushing.” He and his Mafia partner Sam Giancana offered the CIA a counterproposal: give us poison that takes time to kill, so our assassin can escape. Senior officers at the CIA liked the idea. Sidney Gottlieb had a new assignment.

On May 13, 1960, just days after the U-2 fiasco, President Eisenhower ordered Castro “sawed off.” He did not use what CIA security director Sheffield Edwards later called “bad words,” but everyone present understood this as a presidential directive to remove Castro from power by any means including assassination. That gave Richard Bissell and his covert action directorate another murder to plan. Since it would entail making poison and devices by which that poison could be delivered, Bissell turned to what had been the Technical Services Staff, now renamed the Technical Services Division. Sidney Gottlieb was the man for the job.

At first Gottlieb and his chemists concentrated on ways to cause Castro’s downfall by non-lethal means. The first of two options grew out of Gottlieb’s fascination with LSD. As part of his work with the hallucinogen, he had planned an experiment, ultimately canceled because of weather conditions, in which an LSD-laced aerosol would be sprayed into a room of unsuspecting partygoers. He had tested such an aerosol. It might now be sprayed in the radio studio from which Castro made live broadcasts that reached millions of Cubans. If Castro became disoriented and incoherent during one of those speeches, he would presumably lose popular support. This idea was discarded as impractical.

The second option was even stranger. Gottlieb and his team persuaded themselves that part of Castro’s appeal, like the strength of Samson, came from his hair—specifically, his beard. If the beard fell away, they thought, so might Castro’s power. Finding a chemical that would make a beard fall out was just the kind of challenge Gottlieb enjoyed. He chose a compound based on thallium salts. Brainstorming produced the outlines of a plot. The next time Castro traveled outside Cuba, thallium would be sprinkled into the boots he left outside his hotel room to be shined; his beard would fall out, leaving him open to ridicule and overthrow. Gottlieb’s scientists procured thallium and began testing it on animals. Before they could go further, though, this idea’s obvious weaknesses became clear. No one knew when Castro would travel, and even if he stayed at a hotel the CIA could penetrate, his security detail would probably not allow his boots to be handled by strangers. Besides, the idea that Castro’s charisma would disappear with his beard struck some officers as far-fetched. This plot was also aborted.

Gottlieb and his scientists turned their thoughts to assassination. Their first idea was to taint cigars that operations officers would deliver to Castro. The CIA inspector general who later investigated this plot reported that an Agency officer “did contaminate a full box of fifty cigars with botulinum toxin, a virulent poison that produces a fatal illness some hours after it is ingested. [Redacted] distinctly remembers the flaps-and-seals job he had to do on the box and on each of the cigars, both to get at the cigars and to erase evidence of tampering . . . The cigars were so heavily contaminated that merely putting one in the mouth would do the job; the intended victim would not have to smoke it.” The report names Gottlieb as a co-conspirator, although without specifying his role.

“Sidney Gottlieb of TSD claims to remember distinctly a plot involving cigars,” the report says. “To emphasize the clarity of his memory, he named the officer, then assigned to [the Western Hemisphere Division], who approached him with the scheme. Although there may well have been such a plot, the officer Gottlieb named was then assigned in India and has never worked in WH Division nor had anything to do with Cuba operations. Gottlieb remembers the scheme as being one that was talked about frequently but not widely, and as being concerned with killing, not merely influencing behavior.”

The poisoned cigars—Cohibas, Castro’s preferred brand—were passed to a CIA officer. No way was found to use them. After seven years in a CIA safe, one was removed for testing. It had retained 94 percent of its toxicity.

These bumbling attempts hardly satisfied Bissell. He decided to consult professionals. That led him to Roselli, who along with other powerful gangsters had become rich through gambling, prostitution, and drug dealing in Cuba. They meant to destroy Castro before he could carry out his promise to rid the country of crime and vice. Roselli’s contacts in the Havana underworld made him an ideal partner for the CIA.

The gangster’s idea for assassination by poison was timely. The mobster had never heard of Gottlieb—no one had—but he correctly presumed that the CIA must have someone on its payroll who made poison. Stars were aligning. The CIA had made contact with gangsters who wanted Castro dead. The gangsters wanted poison. Gottlieb could provide it.

Finding ways to kill Castro without using firearms—and, at points in the plotting, also to kill his brother Raúl and guerrilla hero Ernesto “Che” Guevara—became one of Gottlieb’s main preoccupations after his return from the Congo. The challenge tested his peculiarly creative imagination. The Castro plot rose to the top of his priority list for the same reason it rose to the top for Bissell and CIA director Dulles. This assassination had been ordered by the president of the United States.

From Eisenhower, the chain of command was short and direct. The president gave his order to Dulles and Bissell. Bissell turned to the redoubtable Sheffield Edwards, who as head of the Office of Security kept the CIA’s deepest secrets. Edwards chose a go-between able to approach Mafia figures without there being clear CIA ties: Former FBI agent Robert Maheu, now a private detective, worked for reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes. Maheu became the conduit through which the CIA passed instructions and devices to gangsters who were to assassinate Castro.

Gottlieb was to provide the method. With scientists at Fort Detrick, he conceived of ways to kill Castro. These included, according to a Senate investigation years later, “poison pills, poison pens, deadly bacterial powders, and other devices which strain the imagination.”

Eisenhower left office in January 1961 but anti-Castro plotting went on. John F. Kennedy proved equally bent on “eliminating” Castro. The CIA’s epically inept 1961 invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs intensified Kennedy’s determination. He and Attorney General Robert Kennedy, his brother, insistently demanded the CIA crush Castro. “The Kennedys were on our back constantly,” Samuel Halpern, who served at the top level of the covert action directorate at the time, said, “They were just absolutely obsessed with getting rid of Castro.” CIA official Richard Helms, who later headed the agency from 1966 until 1973, felt the pressure directly.

“There was a flat-out effort ordered by the White House, the President, Bobby Kennedy—who was after all his man, his right-hand man in these matters—to unseat the Castro government, to do everything possible to get rid of it by whatever device could be found,” Helms later testified. “The Bay of Pigs was a part of this effort, and after the Bay of Pigs failed, there was even a greater push to try to get rid of this Communist influence 90 miles from United States shores . . . The principal driving force was the attorney general, Robert Kennedy. There isn’t any question about this.”

For years, White House pressure kept Gottlieb and his bosses focused on killing Castro. The Technical Services Division considered planting a bomb in what would appear to be a rare mollusk where Castro liked to scuba dive. “None of the shells that might conceivably be found in the Caribbean area was both spectacular enough to be sure of attracting attention and large enough to hold the needed amount of explosive,” a CIA report stated. “The midget submarine that would have had to be used in emplacement of the shell has too short an operating range for such an operation.”

That left poison. Gottlieb and colleagues were tasked with making that substance and imagining how it could be delivered. One idea was based, like the bomb plot, on Castro’s love of scuba diving. President Kennedy had assigned lawyer James Donovan—portrayed by Tom Hanks in the 2015 film Bridge of Spies—to negotiate release of POWs from the Bay of Pigs. The CIA proposed to have Donovan give Castro a tainted diving suit—precisely the kind of job for which Technical Services had been created.

“TSD bought a diving suit, dusted it inside with a fungus which would produce Madura foot, a chronic skin disease, and contaminated the breathing apparatus with a tubercle bacillus,” a CIA officer wrote years later. “The plan was abandoned when the lawyer decided to present Castro with a different diving suit.” These failures brought the CIA, Technical Services, and Gottlieb back to Roselli’s original idea: make poison and find a way to feed it to Castro. “Four possible approaches were considered: (1) something highly toxic, such as shellfish poison to be administered with a pin (which Technical Services Division head Cornelius Roosevelt said was what was supplied to Gary Powers); (2) bacterial material in liquid form; (3) bacterial treatment of a cigarette or cigar; and (4) a handkerchief treated with bacteria,” stated the official summary of a later interview with Roosevelt. “The decision, to the best of his recollection, was that bacteria in liquid form was the best means [because] Castro frequently drank tea, coffee, or bouillon, for which liquid poison would be particularly well suited . . . Despite the decision that a poison in liquid form would be most desirable, what was actually prepared and delivered was a solid in the form of small pills about the size of saccharine tablets.”

The CIA never fully abandoned the idea of killing Castro with firearms. Evidence suggests that the agency arranged to smuggle rifles and at least one silencer into Cuba for this purpose. However, poison remained the most appealing option. During 1961 and 1962, intermediaries working for the CIA passed several packets of Gottlieb’s botulinum pills—called “L-pills” because they were lethal—to gangsters for delivery to contacts in Cuba. One batch could not be used because the Cuban official who was to place the pills in Castro’s food was transferred out of proximity to the Cuban leader. Pills from another batch were to have been slipped into Castro’s food or drink at a restaurant he frequented, but he stopped eating there.

Choosing a poison was not Gottlieb’s only contribution to the Castro assassination project. He and his staff also produced two devices for delivering it. A CIA report describes the first as “a pencil designed as a concealment device for delivering the pills.” More elaborate was what the report calls “a ballpoint pen which had a hypodermic needle inside, that when you pushed the lever, the needle came out and poison could be injected into someone.” According to another description, the needle was “designed to be so fine that the target (Castro) would not sense its insertion and the agent would have time to escape before the effects were noticed.” A CIA officer in Paris handed this pen to a Cuban CIA “asset” on November 22, 1963, the day Kennedy was assassinated.

Lyndon Johnson kept using political and economic means, including sabotage and other covert work, to undermine Cuba’s government. But he decided “we had been operating a goddamn Murder Inc. in the Caribbean,” and ended assassination plots. A Cuban agent given firearms and explosives by the CIA was in contact with the Agency until 1965, but never carried out an attack. Making poison to kill foreign leaders was no longer Gottlieb’s job.