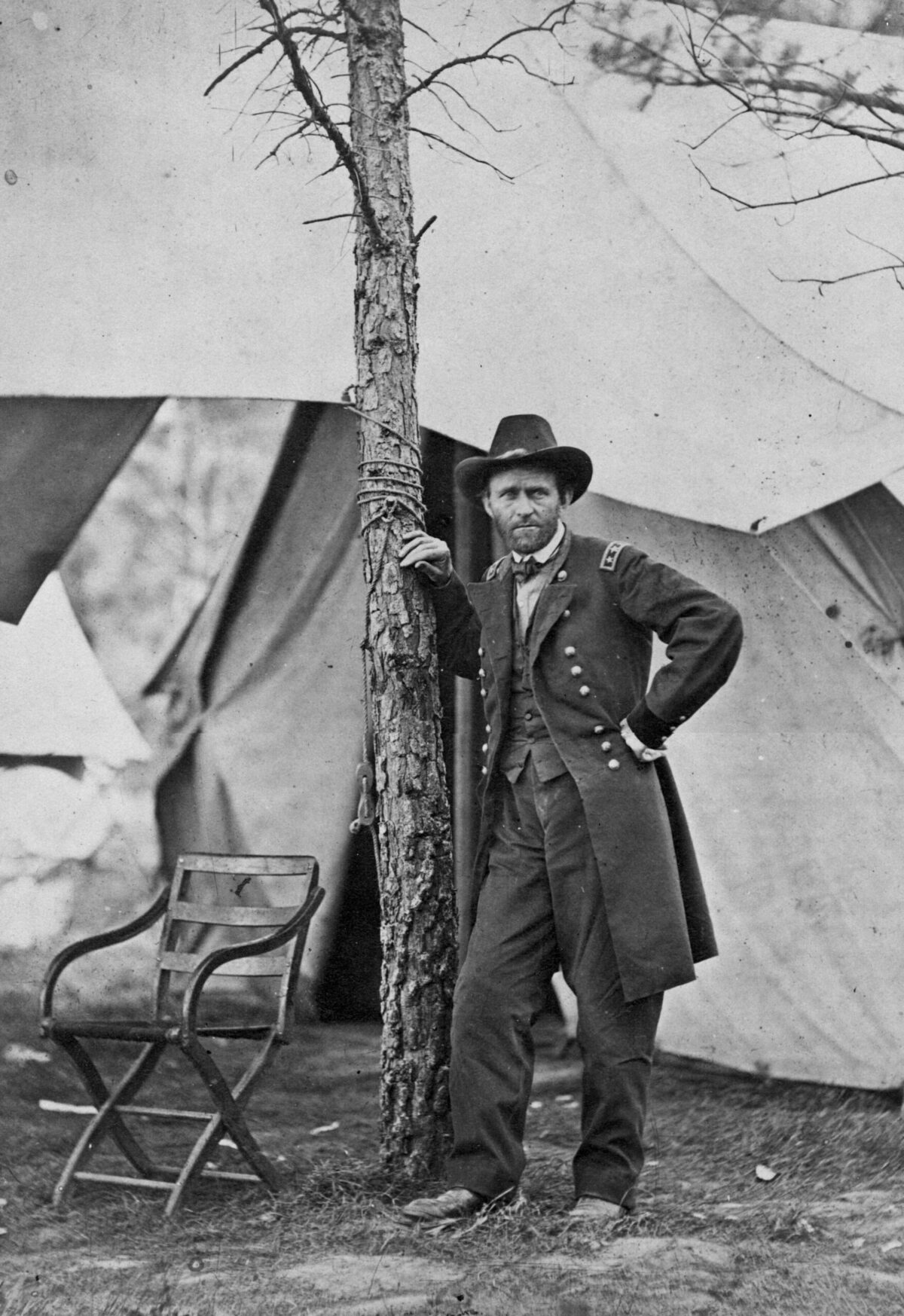

Despite Ulysses Simpson Grant’s stature as one of the leading figures in American history, many mysteries remain about the man. Throughout his lengthy career Grant battled accusations that he was overly fond of the bottle, but did his alleged excessive drinking make him an alcoholic? For that matter, did he really drink that much more that the average man of the nineteenth century?

There was some precedent for alcohol abuse in Grant’s family. Noah Grant, Ulysses’ paternal grandfather, who came from a prominent New England family and had served in the Continental Army throughout the Revolutionary War, turned to alcohol after the death of his first wife. His alcohol consumption became so uncontrollable that it led to his financial ruin and premature death. Noah Grant’s addiction became so bad that after the death of his second wife he abandoned his son, Jesse.

Because of Noah’s failure, Jesse Grant was forced at a very young age to make his way in the world alone, toiling as a laborer on local farms until he eventually found work at the home of Ohio Supreme Court Justice George Tod. His exposure to Tod’s lifestyle and his memories of his father’s destructive alcoholism bred in Jesse a fierce determination to succeed in life. At age sixteen, Jesse apprenticed himself to a tanner to learn a trade and soon began a business of his own. Eventually, through hard work and good business sense, Jesse became successful, and married Hannah Simpson in 1821. On April 27, 1822, not long after the couple settled in Ohio, their first son, Ulysses, was born. Even with continued business success and the birth of four more children, Jesse and Hannah Grant remained dedicated to the ideal of earnest labor and education. Both were stern and intolerant of those who were not willing to work hard and stay sober.

Driven by his belief in hard work and desire to see his son succeed–and no doubt impressed with the austerity of a military education–Jesse Grant procured an appointment to the United States Military Academy for Ulysses. At West Point, Grant received passing grades but did not revel in the Spartan military lifestyle. Like many other young cadets, Grant became exposed to alcohol, but there is no evidence that he overindulged during his time there.

In early nineteenth-century America alcohol consumption was an accepted facet of everyday life. Many Americans consumed liquor because they believed it was nutritious, stimulated digestion, and relaxed the nerves. Liquor was also consumed to help wash down food that was often poorly cooked, greasy, salty, and sometimes even rancid. By 1830, the annual per capita consumption of alcohol by Americans had climbed to more than five gallons. The small, professional army that Grant joined as a second lieutenant after his graduation in 1843 mirrored this widespread societal use of alcohol.

After graduation Grant was assigned to the Fourth Infantry Regiment at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, outside St. Louis. While there, he had an opportunity to become familiar with the family of his West Point roommate, Frederick Dent. During one of his visits to the Dents, Grant met Frederick’s sister Julia. A relationship soon developed between Ulysses and Julia, with Grant spending as much time as possible with the young lady. These visits frequently caused Grant to be late for dinner at the post’s officers’ mess. Interestingly, the fine for being late to dinner was one bottle of wine.

The presiding officer for the mess was Captain Robert Buchanan, a rigid disciplinarian who enforced the rules with a stiff impartiality. The fourth time Grant was late returning to the post, Buchanan informed him that he would again be fined the requisite bottle of wine. Grant, who had already purchased three bottles of wine for the mess, had some words with Buchanan concerning the fine and refused to pay. This trivial confrontation was the beginning of a long-running feud between the two.

Grant received a reprieve from his unpaid mess bills when rising tensions with Mexico caused his regiment to be transferred to Texas. The Fourth Infantry became involved in military operations against Mexico in 1846 and became one of the most heavily engaged regiments of the war. Even so, the regiment also experienced all of the boredom, inactivity, and drinking that was a feature of any army on campaign. It was during such lulls that Grant was known to drink with his peers. However, these episodes were confined to moments of boredom and monotony and were common among many of his fellow officers. Grant emerged from the Mexican War with two brevet promotions, a solid reputation, and a bright future.

Following the war and a brief period of occupation duty in Mexico, Grant returned to St. Louis and married Julia on August 22, 1848. After his honeymoon, Grant began his Regular Army duties. His first posting was to the isolated garrison at Sackets Harbor, New York, where Grant learned garrison duty was a far cry from his adventures in Mexico. While at Sackets Harbor, he was one of many officers who coped with the inactivity of peacetime by cycles of frequent drinking. Worried about his increasingly heavy drinking, Grant joined the Sons of Temperance in the winter of 1851 and became an active participant in the temperance movement. During the remainder of his stay at Sackets Harbor, his involvement with the Sons of Temperance seemed to alleviate the urge to drink.

Grant’s next post, Detroit, Michigan, took him away from the moral support of the Sons of Temperance and reintroduced him to the heavy drinking that was a feature of army life. Grant soon began to confront accusations that he drank too heavily. One of these accusations arose when he brought charges against Zachariah Chandler, a local storekeeper. Like most merchants, Chandler was often too busy minding his store to take the time to clear the ice from the sidewalk. One night, while passing in front of Chandler’s home, Grant slipped and fell on the ice and injured his leg. He angrily filed a civil complaint against the storekeeper. During the subsequent court case, Chandler said in reference to Grant, ‘If you soldiers would keep sober, perhaps you would not fall on people’s pavement and hurt your legs.’ Grant won his complaint, but the case grabbed the attention of the military community in St. Louis and only fed rumors among the officers that Ulysses S. Grant was overly fond of the bottle.

In the spring of 1852 Grant’s regiment was ordered to Fort Vancouver, Oregon. After leaving Julia and his children with his in-laws in Missouri, Grant traveled to New York City for transport to Panama via the steamship Ohio.

Grant, then serving as the Fourth’s quartermaster and responsible for many of the logistic matters that were involved in transporting an infantry regiment, shared quarters with J. Finley Schenck, the captain of Ohio. Schenck later said that Grant was a diligent worker and would continue to conduct his duties after Schenck had gone to bed. The captain remembered that Grant would come in and out of the cabin throughout the evening to drink from whiskey bottles kept in the liquor cabinet. This pattern continued until Ohio arrived in Panama. However, from the time of his coming ashore in Panama to his arrival at Fort Vancouver, Grant was kept so busy with his military responsibilities that he had no time to be idle, and there were no further problems with drinking reported.

Not long after arriving at Fort Vancouver, however, Grant began to battle the boredom and loneliness that came with prolonged separation from his family. Like other officers at the post, Grant turned to the bottle to help pass the time, and many men stationed at the fort later recalled seeing him drink.

Unfortunately for Grant, his small stature and frame ensured that he would start to show the ill effects of alcohol after only a few drinks. Grant’s reputation was further tarnished because he had a tendency to be intoxicated in front of the wrong people. One of those who witnessed his drinking while at Fort Vancouver was future general George B. McClellan. Becoming intoxicated in the presence of officers like McClellan, considered to be among the Army’s best and brightest, spread the question of Grant’s drinking habits to increasingly important people within the Army.

In September 1853 Grant was transferred to Fort Humboldt, California, to fill the captaincy of the Fourth Infantry’s Company F. He was to find the fort more foreboding than any other post he was assigned to during his pre-Civil War career. Since the fort was located in an isolated area of northern California, Grant’s military life became slow, tedious, and monotonous. He watched his subordinates do most of the routine work and the Indians in the area remained peaceful. Things were so boring that Grant spent much of his time at Ryan’s Store, a local trading post that served liquor.

The time that Grant passed at Ryan’s did not go unnoticed by Fort Humboldt’s commander, Lt. Col. Robert Buchanan. This was the same Robert Buchanan with whom Grant had argued at Jefferson Barracks many years previously. Buchanan still harbored a strong dislike for Grant. He used his position as the post commander to make life unbearable for the captain and helped spread rumors that Grant was intemperate.

Made miserable by Buchanan and missing his family, Grant began to consider resigning his commission. One night he imbibed more than usual, and when he reported for duty the next day, he appeared to still be intoxicated. Buchanan became furious and put Grant on report for drunkenness while on duty, instructing him to draft a letter of resignation and to keep it in a safe place. After a similar instance of late-night drinking a short time later, Buchanan requested that Grant sign the letter of resignation he had drafted earlier or he would be charged with drunkenness while on duty.

Facing a court-martial, Grant decided that it was time to resign. On April 11, 1854, he sent his signed letter of resignation to the secretary of war. Grant had served in the Army for fifteen years, performed well, and gained valuable experience. During those fifteen years, he had occasionally indulged in periods of drinking, but these generally had been confined to social occasions or when he had little to occupy his time and was separated from his family. There is no indication that prior to his resignation Grant drank more than was typical for a man of the time. Unfortunately, Grant incautiously allowed others to see him when inebriated, and he left the Army with a reputation as a heavy drinker.

With Colonel Buchanan, Fort Humboldt, and his army career now behind him, Grant turned his attention to farming. For three years he tried to make a living from the land before giving up in 1858. After the failure of the farm, he unsuccessfully attempted a number of jobs, and was eventually forced to return to his father’s home and work in the family tanning shop in Galena, Illinois.

Despite such disappointments, Grant was content. Reunited with Julia and busy with the demands of supporting his family, he had neither the time nor the inclination to drink and was able to lead a sober life.

After the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the former army officer proffered his services to the recently appointed commander of Ohio’s militia, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. When he did not get a response from McClellan, who no doubt remembered Grant from Fort Vancouver, Grant offered his services to Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon in St. Louis. Again, he received no response. Evidently, Grant was haunted by his reputation as a drunk.

Frustrated, Grant returned to Galena to help process paperwork and muster local volunteers into service. Although he had hoped for a regimental command, this time spent mustering in raw recruits was important–it brought him to the attention of Congressman Elihu B. Washburne. Realizing his capability as a soldier and organizer, Washburne persuaded Illinois Governor Richard Yates to appoint Grant colonel of the Twenty-first Illinois Infantry Regiment. The Twenty-first had been a problem regiment, but Grant quickly brought discipline to the unit and turned it into an effective fighting force. Having proven his ability as a colonel, Grant was promoted to brigadier general in July 1861.

Grant then went to see Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont, commander of the Army’s Western Department, hoping to obtain a command in Missouri. Most members of Fremont’s staff wanted him to ignore Grant, but Major Justice McKinsty, Fremont’s aide, argued on Grant’s behalf. Grant got the position, and it proved to be the break he needed. He rapidly moved through a series of departmental commands, and in early 1862 led the Tennessee expedition that forced the capitulation of Forts Henry and Donelson, vital Southern strongholds on the Tennessee River.

While his victories at Henry and Donelson earned Grant higher command, they also carried the accusations of his drinking to a wider audience. Reporters and officers jealous of Grant’s fast rise, as well as disillusioned civilians, used the perception of Grant as a drunkard in an attempt to explain the horrific losses suffered at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862.

Shocked by the casualties of what up to that point was the war’s bloodiest battle, many newspaper reporters wrote articles critical of Grant’s command. These criticisms fed the rumors that Grant, who many believed had been forced from the Army because of his love of the bottle, had been caught drunk and off guard by Confederate General Albert Sydney Johnston’s surprise attack.

The losses suffered by both sides at Shiloh had more to do with the nature of nineteenth-century warfare than the nature of Grant’s relationship with liquor, but rumors of his affection for spirits now became generally accepted. Those who were jealous of Grant’s success helped spread the rumors. While it was true that Grant had begun to drink again after avoiding alcohol in the years before the start of the war, there are no reported incidents of him drinking excessively prior to the start of the Vicksburg campaign in late 1862. Major John Rawlins, a close member of Grant’s personal staff who took it upon himself to keep Grant temperate, went to great lengths to defend Grant against accusations that he had been drinking during the battle.

Despite the persistent rumors of his Shiloh drunkeness, Grant pressed on. In November 1862 he began his campaign to capture the Mississippi River port of Vicksburg, the key to Southern control of the river. Unable to quickly defeat the Confederate forces, by May 1863 Grant had been forced to begin a protracted siege of the city. It was during this lengthy siege, and while he was again separated from his family for a prolonged period of time, that the most well-documented instances of Grant’s drinking took place.

The first occurred on May 12, 1863. Sylvanus Cadwallader, a newspaper reporter who had attached himself to Grant’s staff and was following the progress of the campaign, was sitting in the tent of Colonel William Duff, Grant’s chief of artillery, carrying on a casual conversation. Suddenly, Grant stepped in. Duff pulled out a cup, dipped it into a barrel that he had stored in his tent, and handed the cup to Grant. Grant drank the contents and promptly handed the cup back to Duff. This procedure was repeated two more times, and Grant left the tent. Cadwallader then learned that the barrel contained whiskey. Duff had been ordered by Grant to keep the barrel handy for his exclusive use.

Less than a month later, Cadwallader recounted the most infamous tale of Grant’s drinking during the war. It began on June 3 during an inspection tour to Satartia, Mississippi, on the Yazoo River. The siege was agonizingly slow, and Grant had been separated from Julia since April. To alleviate his boredom, he had decided to travel up the Yazoo. During his trip, Grant encountered the steamboat Diligence carrying Cadwallader downriver from Satartia. Grant decided to board Diligence, and according to Cadwallader: ‘I was not long in perceiving that Grant had been drinking heavily, and that he was still keeping it up. He made several trips to the bar room of the boat in a short time, and became stupid in speech and staggering in gait. This was the first time he had shown symptoms of intoxication in my presence, and I was greatly alarmed by his condition, which was fast becoming worse.’ For the next two days, Cadwallader tried unsuccessfully to stop Grant from drinking and did his best to keep him from trouble. By the time Grant finally arrived back at his headquarters, he had sobered up.

The final incident occurred in July after the surrender of Vicksburg when Grant traveled to New Orleans to discuss operations with Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks. On September 4, Grant, Banks, and their respective staffs rode out to review the troops stationed in New Orleans. Banks had given Grant a large, untamed charger as a gift, and Grant elected to take the horse on the inspection. The animal proved very spirited, and following the inspection Grant had the horse moving at a fast gallop on the return trip into the city when the horse lost its footing and fell, severely injuring the general. Almost from the moment that the unfortunate beast slipped, rumors began circulating that the general had been drunk during the ride. However, there was never any evidence to prove that an intoxicated Grant caused the horse to fall.

From the New Orleans incident until the end of the war in April 1865, there are no stories of Grant’s drinking to excess. Rumors of alcohol abuse continued to hound him, but no evidence suggests that Grant ever repeated his bender of June 1863.

While the severity of Grant’s drinking problem was clearly magnified by rumor, it does seem clear from his drinking that Grant had inherited some of his grandfather’s fondness for the bottle. Yet, unlike his grandfather, Grant was largely able to control his drinking thanks to the help of people close to him and his own willpower and sense of duty.

Grant seemed to experience his greatest temptation to drink during long periods of inactivity or when he was away from his family. When he became commanding general of the Army, he was able to bring Julia and his oldest son to his headquarters. Julia had always been Grant’s strongest supporter in his battle with alcohol, and with her present, Grant stayed sober.

By today’s standards, Grant could be considered an alcoholic, but he was able to control his addiction. As Grant biographer Geoffrey Perret explained: ‘The entire staff, as well as most of Grant’s division and corps commanders, was well aware of his drinking problem. [Brig. Gen. John A.] McClernand tried to make capital out of it and one or two other officers expressed their disgust at Grant’s weakness, but to the rest, it did not matter. A few were alcoholics themselves, but the main reason it was tolerated was that when Grant got drunk, it was invariably during quiet periods. His drinking was not allowed to jeopardize operations. It was a release, but a controlled one, like the ignition of a gas flare above a high-pressure oil well.’

Grant learned how to cope with his addiction to liquor by learning when he could take a drink. Although difficult at times, Grant was able to control his sickness and rely on his ability as a natural leader to achieve victory on the battlefield. As historian James McPherson explained: ‘In the end…his predisposition to alcoholism may have made him a better general. His struggle for self-discipline enabled him to understand and discipline others; the humiliation of prewar failures gave him a quiet humility that was conspicuously absent from so many generals with a reputation to protect; because Grant had nowhere to go but up, he could act with more boldness and decision than commanders who dared not risk failure.’ Consequently, Grant was able to overcome personal failures and adversity and become a well-respected and adored man in later life.