It was a fine spring day on May 5, 1945, as Boatswain’s Mate Joe Burbine scanned the horizon from Coast Guard Station Point Judith in Rhode Island. From this vantage at the entrance to Narragansett Bay the enlisted lookout had a clear view of the comings and goings of ships.

The mood at the station was upbeat. World War II in Europe was essentially over. Adolf Hitler was dead, and the Nazi regime was collapsing under the weight of a relentless Allied assault. Surrender was expected at any moment.

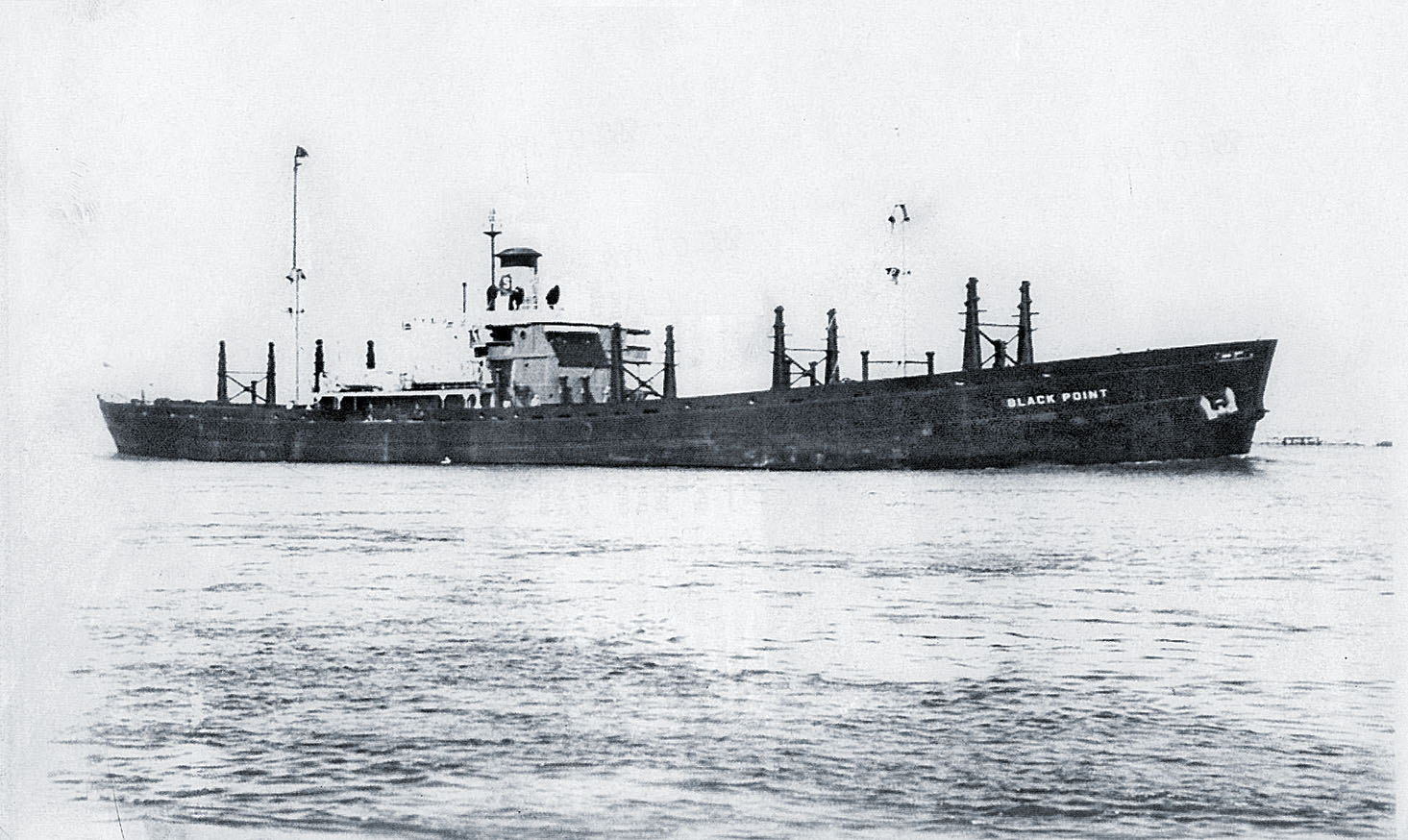

In that relaxed milieu Burbine watched unconcerned as the collier SS Black Point chugged north. Laden with some 7,600 tons of coal and crewed by 46 men, the ship passed about 2 miles off the point, headed to Boston at roughly 8 knots in fair seas.

Around 5:40 p.m., as evening approached, Burbine bent down to record the sighting in the station logbook. Startled by a muffled explosion, he raised his binoculars and looked to sea, watching in horror as a plume of water shot skyward alongside Black Point. A torpedo had struck the collier, blowing off its stern.

Seventy-six years ago the prospect of an end to the long war was shattered within sight of the American coast. A German U-boat had slipped into the shallow waters off New England and launched an attack that sent a chill of fear through American sailors and merchant mariners. The German submarine captain, either ignorant of a stand-down order from his superiors or ignoring the command, remained on the hunt for prey.

World War II was not yet over. The Battle of Point Judith—the final naval engagement in the Atlantic campaign—had only just begun.

From the outbreak of war in 1939 through early 1943 Germany held the upper hand in the wide-ranging Battle of the Atlantic. Its submarines sank cargo vessels, troop transports, oilers and warships at an alarming rate. U-boats decimated Allied shipping along the East Coast during Unternehmen Paukenschlag (Operation Drumbeat), which began in January 1942, within weeks of the U.S. entry into the war. German submariners dubbed it the “Second Happy Time” (the “First Happy Time” having come in 1940–41 in the North Atlantic and North Sea). In the first eight months of 1942 the U-boats sank more than 600 ships totaling 3.1 million tons.

Then the tide turned. Improved anti-submarine tactics, new weapons and technologically advanced underwater detection systems gave the U.S. Navy the advantage. Soon the hunters became the hunted. Allied shipping losses fell dramatically, while U-boat sinkings climbed month by month. By war’s end Germany would lose 783 subs and some 30,000 men in the Atlantic. Suffering 75 percent losses, the Kriegsmarine U-boat service had a higher death rate than any branch in the armed forces of all of the conflict’s combatant nations.

The captain of U-853 was certainly aware of the state of affairs when he took to sea on Feb. 23, 1945, for his last patrol. Though just 24, Oberleutnant zur See Helmut Frömsdorf was already a veteran of submarine warfare. He had served on U-853 since its first combat patrol in 1944, quickly learning of the inherent dangers from his first commander, Kapitänleutnant Helmut Sommer.

U-853, a Type IXC/40 long-range submarine carrying 22 torpedoes, had been tasked with collecting weather data, which German intelligence believed would help predict the timing of the anticipated Allied invasion of Europe. On May 25, 1944, Sommer spotted one of the greatest potential prizes of all—RMS Queen Mary. Pressed into service as a troopship, the elegant British ocean liner was carrying U.S. troops and supplies to Britain in the run-up to D-Day. Sommer submerged his U-boat and went in pursuit but was unable to catch the much faster ship.

During that same patrol U-853 earned its nickname, Seiltänzer (“tightrope walker”), after narrowly evading an American anti-submarine hunter-killer group. For three weeks Sommer and crew played a deadly game of cat-and-mouse with the escort carrier USS Croatan and a half dozen destroyers, which had intercepted the U-boat’s weather transmissions.

On June 17 Croatan launched a pair of Eastern Aircraft FM-1 Wildcat fighters, which caught U-853 on the surface and strafed it, killing two German sailors and wounding a dozen. Sommer himself sustained 28 wounds from shrapnel and bullets, yet survived. The captain refused to leave the conning tower until the injured were moved below-decks. Taking the helm, Frömsdorf managed to elude the hunter-killer group. After returning to France for repairs, U-853 logged a second patrol off Britain with another captain. After that unsuccessful mission Frömsdorf was given command.

U-853’s new skipper was an atypical U-boat captain. Standing 6 feet 10 inches, Frömsdorf was likely the tallest man in the German submarine service. We can only guess at how many times he banged his head or stooped beneath a bulkhead in the cramped confines of U-853.

Before leaving Germany, Frömsdorf visited his former captain in the hospital. Sommer cautioned the junior officer about the mission and told him the war was at an end. “Do not be frivolous with the crew,” the wounded commander urged. “They are all good boys. Make sure you bring them home.”

Sommer’s plea apparently fell on deaf ears. Though not a Nazi Party member, Frömsdorf was an idealogue. He firmly believed Nazi propaganda and strove to serve the Fatherland, no matter how the war was going. He may also have been a Halsschmerzen (“sore throat”)—a term the German military used to describe a glory-seeking commander who would risk his men in his obsession to earn a Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross—Nazi Germany’s highest award. The Kriegsmarine referred to such reckless U-boat commanders as Draufgängeren (“daredevils”).

Capt. Bill Palmer, author of The Last Battle of the Atlantic: The Sinking of the U-853, is convinced that was the case with Frömsdorf. An avid scuba diver and owner of a charter boat operation out of Mystic, Conn., Palmer has dived on the wreck many times.

“I spoke to a number of U-boat officers and sailors and was told Frömsdorf had a ‘sore throat,’” Palmer said. “He was looking to distinguish himself before the war ended. But you don’t do that when 50 men are depending on you for survival.”

On Feb. 23, 1945, U-853 slipped into the Atlantic, bound for the East Coast. The vessel made slow progress, as it traveled underwater most of the way to avoid detection by Allied aircraft. Before sailing, the submarine had been outfitted with a newly refined snorkel, a telescoping air-intake apparatus that enabled a submerged U-boat to use its diesel engines.

Once underway Frömsdorf received orders to proceed to the Gulf of Maine. On the afternoon of April 23, as U-853 patrolled Casco Bay, off Portland, its sonar operators detected the engine noise of a nearby ship, USS Eagle 56. Assigned to Naval Air Station Brunswick, the World War I–era patrol boat was towing a target so U.S. aircraft could practice dropping bombs on seaborne objects.

At 12:14 p.m. Frömsdorf launched a single G7e torpedo toward the unsuspecting vessel. The weapon’s 660-pound warhead exploded amidships, breaking Eagle 56 in two. The 200-foot patrol boat sank in minutes, taking 49 men with it to the bottom of Casco Bay. A half hour later a destroyer arrived to pluck 13 survivors from the cold sea.

Within weeks a U.S. Navy board of inquiry determined Eagle 56 had succumbed to a boiler explosion, despite the fact survivors reported having seen a U-boat conning tower with distinctive red-and-yellow markings. (Painted by its crew, U-853’s emblem was a red horse on a yellow shield.) The board’s finding stood until 2001, when naval historian Paul Lawton presented conclusive evidence a torpedo had sunk the ship. The Navy subsequently issued Purple Hearts to the survivors and next of kin of those killed.

Ironically, Eagle 56—the last American warship sunk in the Atlantic—had on Feb. 28, 1942, rescued survivors of the torpedoed destroyer USS Jacob Jones—the first American warship sunk in the Atlantic after Germany declared war on the United States.

Following the Casco Bay attack, U-853 took evasive action and escaped detection by U.S. sub hunters. Frömsdorf then headed the U-boat south in search of other targets.

By May 5 U-853 had moved into position off Point Judith. That same day Grossadmiral Karl Dönitz—who in the wake of Hitler’s April 30 suicide had succeeded the Führer as Reichspräsident—had a radio message beamed to all U-boat captains, ordering them to cease offensive operations and return to base.

Did U-853 receive the message? It’s possible the U-boat was submerged without its antennae deployed and never heard the transmission. Of course, it’s also possible Frömsdorf received message and simply ignored it so he could sink more enemy shipping. What exactly transpired that day will never be known, as the logbook was not recovered.

“Did he get the message and ignore it?” posited Robert Cembrola, director of the Naval War College Museum in Newport, R.I., which showcases a range of U-853 artifacts. “Did he see that big freighter going by and say, ‘I’m going to get one more kill before I head back to Germany’? That’s a big question.”

If Frömsdorf did disregard Dönitz’s order to cease hostilities, it wouldn’t be the only time. While hunting for additional targets, he violated another of the admiral’s directives: U-boats were required to be in at least 200 feet of water when attacking, so they could submerge deep enough afterward to avoid detection by the enemy. Frömsdorf would have known from his charts that the bottom where he lay in wait off Point Judith was only 100 feet, thus leaving no place to run and hide if and when sub hunters came looking for him.

Three days before U-853 arrived off Point Judith the heavily loaded collier SS Black Point had steamed out of Newport News, Va., bound north for Boston. Capt. Charles E. Prior wasn’t too concerned about enemy action. The war in Europe was nearly over, and the chances of an attack seemed remote. Twenty minutes till 6 on the evening of May 5, as the collier approached Point Judith Light, Prior stepped from the wheelhouse to smoke a cigarette. Suddenly, the whole ship rocked violently.

“That’s when it hit the fan,” Prior told author Palmer when interviewed for The Last Battle of the Atlantic. “The clock was blown off the wall, and the barometer off the bulkhead. The wheelhouse door was blown open, and I don’t remember if I lit the cigarette or swallowed it. I could smell gunpowder in the air, and the stern of my ship was completely blown off.”

Black Point had been struck by one or more G7e torpedoes fired by U-853. The collier shook with the brutal force of the blast. The severed stern sank within minutes, taking all but one of the men in that section of the ship to the bottom. The only survivor from the fantail was Stephen Svetz, a member of the civilian vessel’s U.S. Navy Armed Guard gun crew. Thrown into the air by the explosion, he landed on the forward section of the ship.

What was left of Black Point drifted for a quarter mile or so before finally coming to a stop and sinking. As he moved through the wreckage looking for injured men, Prior gave the order to abandon ship. Thirty-four survivors made it to the life rafts and were rescued by nearby vessels or crash boats from shore. Twelve crew members either died in the blast or drowned when the collier sank. Black Point was the last vessel sunk in U.S. waters by a German U-boat.

From his post at the Coast Guard station Boatswain’s Mate Burbine notified superiors, who contacted the First Naval District headquarters in Boston, which relayed the message to the Navy’s Eastern Sea Frontier command in New York City. Its radio operators in turn put out a call to Task Group 60.7, then returning to the Massachusetts port from escort duty for repairs and resupply. Three of its four ships—the destroyer escorts USS Amick and Atherton and frigate USS Moberly—were less than 30 miles from the scene of the attack.

The trio of warships arrived around 7:30 p.m. and began a sonar sweep. Within the hour they detected an object on the seafloor at a depth of 108 feet. Atherton immediately dropped magnetic depth charges, one of which exploded, indicating it had struck metal. The crew then fired two rounds of hedgehogs, a mortar-like, forward-throwing anti-submarine weapon whose warheads also only detonated on contact.

Soon joining the hunt was the destroyer USS Ericsson, the fourth member of TG 60.7. The American warships initiated another sonar sweep but were unable to pinpoint the U-boat. Uncertain whether the initial target had been an existing shipwreck or the enemy sub, the Navy commanders widened their search grid.

Around 11:20 p.m. Atherton and Moberly, working together, detected what they believed was the U-boat, in 100 feet of water some 4,000 yards east of the original attack zone. Closing in, the American warships fired several rounds of hedgehogs. When crew members brought searchlights to bear 30 minutes after midnight on May 6, their beams picked up bubbles, oil and debris on the surface.

Atherton circled the area for some 20 minutes, maintaining sonar contact with the target on the seafloor. No movement or sounds were detected. Just in case, the ship dropped two more series of depth charges on shallow settings. One exploded too soon and damaged Atherton’s own sonar gear, so Moberly moved in to attack. Incredibly, sonar showed U-853 was still “alive” and creeping along the bottom at about 5 knots.

During its depth-charge run Moberly experienced the same problems as Atherton had, the resulting shallow explosions also damaging its sonar. The crew made repairs. But the U-boat managed to slip away after being detected moving at 2 to 3 knots in 75 feet of water.

As dawn broke, it became clear the depth charge and hedgehog barrages had hit the mark. Lookouts spotted three oil slicks about 30 feet apart, along with considerable debris. After re-establishing sonar contact, the warships resumed their attack at 5:30 a.m., making multiple runs with depth charges and hedgehogs. A pair of Navy blimps from Lakehurst, N.J., soon joined in, marking the target and firing rockets at the oil slicks.

In a coup de grâce, Atherton and Moberly made a last run at the U-boat with depth charges. The former went first, followed by the latter. After Moberly passed over the target, an eruption of air and oil broke the surface, followed by all manner of equipment, papers and clothing, including Frömsdorf’s black-peaked cap. The sub hunters broke off their attack at 10:45 a.m.

That same morning the submarine rescue ship USS Penguin departed New London, Conn., bound for the battleground. Most of the vessel’s crew members were bleary-eyed and deeply hungover after a late night of partying. They’d been celebrating what they thought was the end of the war in Europe. On May 7—the day Nazi German emissaries initially surrendered to the Allies—divers from Penguin descended on U-853. Their mission was to identify the sub and rescue survivors. No one believed there would be any.

The divers found what they expected—a severely damaged U-boat and the bodies of 55 officers and men in and around the wreck. Breaching the hull were two holes—one forward of the conning tower, the other near the engine room. The divers tried entering the U-boat through the narrow main hatch but found it blocked by several corpses. They extracted one body and brought it to the surface. It was later identified as that of 22-year-old seaman Herbert Hoffmann, whom a pathologist determined had succumbed to injuries rather than drowning. Hoffmann was later buried at sea with full military honors. In 1960 divers recovered a complete set of bones. The unidentified remains were interred at Island Cemetery Annex in Newport in a ceremony attended by West German and U.S. Navy officials and representatives.

“We have German officers at the Naval War College every year,” museum director Cembrola said. “On the anniversary of the sinking they have a ceremony here at the cemetery to remember the German sailor who was buried there.”

At one point there was talk of raising the wreck of the U-boat and turning it into a tourist attraction. But when officials in both Rhode Island and West Germany raised objections, the plans were dropped.

In 1953 salvors raised U-853’s twin screws, which for years sat neglected in a field near Newport’s Castle Hill Light. Today the preserved propellers are on permanent display at the U.S. Naval War College Museum.

U-853 rests in 130 feet of water some 7 nautical miles east of Block Island. As it holds the remains of 53 sailors, it is considered a war grave under international maritime law. That doesn’t stop recreational divers from visiting the wreck, one of the most popular dive sites in New England, though due to the U-boat’s deteriorating condition, confined spaces and unexploded ordnance, entering can be dangerous. Two divers have died on the wreck.

The Battle of the Atlantic was costly for both sides. American losses alone totaled 1,600 ships carrying some 14 million tons of materiel, with 9,521 merchant mariners lost to U-boat attacks.

While the sinking of U-853 was a relatively minor event in that long battle for control of the ocean separating the Old World from the New, the loss of the sub remains “a tragic story,” Palmer says. “Capt. Sommer told Frömsdorf the war is nearly over. ‘These are all good boys. Make sure you bring them home.’ And there they sit off Block Island, waiting to go home. It was a tragedy that didn’t have to happen.”

Palmer also interviewed former U-boat commander Herbert A. Werner, not long before the latter’s death in 2013. Werner spoke of the many brave men who served in the Unterseeboote and of the pointless final mission of U-853.

“We were not Nazis, as foreigners depict us, although there were a few,” he said. “We were German sailors, and damned good ones. We did our job until the very last day, and for that I am proud.” MH

Massachusetts freelancer Dave Kindy is a frequent contributor to Military History and other Historynet magazines, as well as other outlets. For further reading he recommends The Last Battle of the Atlantic: The Sinking of the U-853, by Capt. Bill Palmer; World War II Rhode Island, by Christian McBurney, Brian L. Wallin, Patrick T. Conley, John W. Kennedy and Maureen A. Taylor; and “Kill and Be Killed? The U-853 Mystery,” by Adam Lynch, in the June 2008 issue of Naval History.