In 1793, after a frustrating decade as a beached peacetime officer, Royal Navy Captain James Saumarez found victory—and lasting fame—in battle off Cherbourg.

By the closing decade of the 18th century the dividends of relative peace Great Britain had enjoyed since the end of the American Revolution were bankrupting many of King George III’s senior naval officers. Though the men technically remained in the Royal Navy, they received reduced pay unless on active service afloat.

Among those facing increasingly dire financial straits was Captain James Saumarez. He had seen action on the North American station, off Dogger Bank in the North Sea and in the West Indies, the latter as captain of the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Russell. But after paying off the ship’s crew in September 1782, the newly promoted post captain had found himself without a billet and returned to his native Guernsey, where he had spent much of the next decade ashore. Twice during that period he had been called to active service, and twice sent home before he could get to sea. By late 1792 Saumarez longed for a seagoing commission.

Among those facing increasingly dire financial straits was Captain James Saumarez. He had seen action on the North American station, off Dogger Bank in the North Sea and in the West Indies, the latter as captain of the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Russell. But after paying off the ship’s crew in September 1782, the newly promoted post captain had found himself without a billet and returned to his native Guernsey, where he had spent much of the next decade ashore. Twice during that period he had been called to active service, and twice sent home before he could get to sea. By late 1792 Saumarez longed for a seagoing commission.

Though the beached naval officer didn’t yet realize it, he was about to get the command he wanted and so desperately needed.

That James spent his time ashore on Guernsey was only natural, given that his family roots on the island in the English Channel stretched back nearly 600 years. The Scandinavian clan had arrived on Guernsey via France in the early 13th century. Their surname (pronounced Sommerez) was originally de Sausmarez, but James and his brothers had dropped the French “de” and the second “S.” Once prominent, the family had seen a downturn in its fortunes over the centuries until forced to sell the hereditary manor. It was another long-standing tie—to the Royal Navy—that had provided a means of restoring both the family name and fortune.

Saumarez’s paternal grandfather had been a privateer, but two of his uncles had joined the Royal Navy, beginning the family association with Britain’s “Senior Service.” Philip de Sausmarez had circumnavigated the globe as part of Commodore George Anson’s famed 1740–44 expedition. His share of prize money—notably from the Spanish treasure galleon Nuestra Señora de Covadonga, captured in 1743—had enabled him to repurchase the family home and make strides toward restoring the family fortune before dying in battle against a French fleet in 1747 during the War of the Austrian Succession. Another uncle, Thomas de Sausmarez, as captain of HMS Antelope, had captured the French vessel Belliqueux in the Bristol Channel in 1758 and later commanded it in the West Indies. But James Saumarez’s prospects of matching his uncles’ feats dimmed the longer he idled ashore.

In 1787, with hostilities against France in the offing, the Admiralty had appointed Saumarez commanding officer of the frigate Ambuscade, but scarcely had he completed fitting out the ship when ordered to stand down and pay it off. Beached once again, Saumarez had married Martha Le Marchant in October 1788, and the couple later moved from Guernsey to Exeter in southwest England. In 1790, with the threat of war with Spain looming on the horizon, Saumarez had received orders to command HMS Raisonable. Just as before, however, he had yet to put to sea before ordered to stand down and pay off its crew.

Saumarez’s thoughts likely drifted back to those abortive “commands” when in December 1792 the Admiralty appointed him to command HMS Crescent. Launched in 1784, the fifth-rate frigate was 137 feet long and carried just 36 guns. It was no Raisonable and certainly no Russell. But Saumarez was approaching his 36th birthday and had a young family to support, so he was in no position to hold out for a ship of the line. Besides, command of a frigate often meant independent action and the prize money that potentially went with it. Saumarez readily accepted the billet, hoping this time actually to get under way.

He’d get his wish.

In the city of Bath, west of London, an officer sat contemplating a letter from the Admiralty, dated Jan. 14, 1793, urging him to accept Captain Saumarez’s offer to serve on Crescent as third lieutenant. Unlike Saumarez, Lieutenant Peter Rye had enjoyed steady employment in His Majesty’s navy. In March 1791 he had been appointed first lieutenant of the 64-gun ship of the line HMS Diadem. More recently Rye had sailed under Captain John Parker in the fifth-rate HMS Gorgon to New South Wales, where the ship had disembarked Royal Marines and some 31 convicts. On its return voyage Gorgon had taken on the last of the marines assigned to the penal colony. At the Cape of Good Hope the ship had picked up a group of escaped convicts and 10 of the mutineers from HMS Bounty, returning them to England to stand trial. From the time the ship arrived in Portsmouth in June 1792, Rye had been seeking to return to New South Wales.

Like Saumarez, Rye came from a prominent family. His great-grandfather had served the royal court as a gentleman of the Privy chamber. His grandfather had been both archdeacon and regius professor of divinity at Oxford, and his late father had been a respected physician. Unlike his three Oxford-educated older brothers, however, Peter had chosen to go to sea at age 13, and by the time he received the letter from the Admiralty, he had been a “marine animal” for nearly 15 years. While the expected channel duty may not have been as enticing as a voyage to the South Seas, it was a paying commission, and Rye wrote to accept the offer. As third lieutenant Rye would be responsible for the condition of the ship’s firearms and for instructing crewmen in the use of small arms. During battle he would command those armed with pistols and muskets.

Saumarez requested George Parker to serve as Crescent’s first lieutenant. Descended from a former archbishop of Canterbury, Parker was also a nephew of Admiral Sir Peter Parker, who had been Saumarez’s commanding officer on the North American station. The younger Parker had seen a good bit of action during his time at sea, most recently serving aboard HMS Phoenix on a voyage to the East Indies, returning home in October 1792 with dispatches from Commodore William Cornwallis, brother of General Charles Cornwallis. Saumarez rounded out his wardroom with Charles Otter as second lieutenant. The commissions of all four officers were signed and dated Jan. 24, 1793.

The commander and crew quickly turned to fitting out Crescent for sea, and there wasn’t a moment to spare. France declared war on Britain on February 1, and official word reached Saumarez nine days later in a letter Rear Adm. Sir Hyde Parker sent to the fleet, directing his officers “to seize or destroy all ships and vessels belonging to France that you may happen to fall in with.”

It was exactly the sort of order Saumarez had hoped for.

Crescent was ready for sea by March 1, and Saumarez was ordered to sail for Guernsey in convoy with the armed brig Liberty and three transports to reinforce the Channel Island garrisons. On arrival Saumarez received intelligence of a French brig standing for the Casquets, a group of rocks west of the northernmost island of Alderney. He set a course to intercept the vessel. The following morning off Cherbourg Crescent fell in with the 100-ton French ship, which was heavily laden with salt and bound for Le Havre. Saumarez snapped it up without incident, his first taste of success in his new command.

In late May Crescent sailed in company with the frigate Hind, their orders to cruise the channel “for the protection of the trade.” About a month later Saumarez was rewarded with his second prize, the 10-gun cutter Le Club de Cherbourg, which he captured off the coast of Ireland, again without incident.

Meanwhile, Captain Edward Pellew, commanding the 36-gun frigate Nymphe, succeeded in taking the 36-gun French frigate Cléopâtre in the channel. After a sharp, short action between the two ships on the morning of June 18, Nymphe’s crew boarded and seized the French vessel, the first enemy frigate captured during the war. The action was much celebrated, and Pellew was promoted and knighted as a result. Saumarez wrote to younger brother Richard, confessing his anxious desire to achieve similar glory.

In subsequent weeks Crescent carried out such routine duties as escorting convoys while patrolling for enemy vessels. On July 18 Saumarez was given command of a squadron of frigates and was sailing in company with Concorde and Thames when caught in a storm on August 17. Concorde soon became separated from the others, while Thames lost its bowsprit and sailed for home. Crescent fared no better—the gale sprung its main yard and carried away its main topmast. Saumarez limped back to Portsmouth late and empty-handed. Worse yet, Crescent would be laid up in dock under repair for six weeks. Saumarez made the most of his downtime by sending for his family.

Crescent was again fit for sea on October 10. Despite being 13 men short of a full complement, Saumarez reported the frigate ready for duty. Admiral Parker, by then commander in chief of Portsmouth, directed the eager officer to be “in constant readiness to put to sea at a moment’s warning.” That warning came eight days later in orders from the Admiralty directing Saumarez to immediately proceed to Guernsey and Jersey to deliver certain packets and then cruise off Saint-Malo to determine the strength of French forces there.

For several days reports had filtered in regarding two Cherbourg-based enemy frigates said to patrol the channel at night for British merchantmen and then return to port at dawn with their prizes. As Crescent got under way on the evening of October 19, Saumarez resolved to end these depredations. By dawn the following morning the British warship had raised the lighthouse off Cape Barfleur.

The wind had blown westerly during the night, but with the rising sun it shifted south, which would hamper a French ship’s return to Cherbourg. Shortly after dawn a lookout aboard Crescent sighted two sails to leeward. Saumarez, who was sailing on a port tack with the wind offshore, kept to his course to avoid spooking his prey. The French ships approached within 2 miles of Crescent before realizing it was a British frigate. The larger of the enemy vessels, also a frigate, tacked and crowded on sail in a desperate effort to elude its pursuer. Its consort, a cutter, made sail to windward in flight toward Cherbourg.

Saumarez ordered his men to prepare for action. The ship’s gunners ran out their 18-pounders and stripped to the waist as Royal Marine sharpshooters climbed into the mast’s crosstrees. Sand was sprinkled on the deck to absorb the anticipated bloodshed and to give the barefoot crewmen a better grip on the deck. All aboard Crescent realized they were chasing a frigate, not some poorly armed brig or cutter. The French warship wouldn’t just heave to and wait to be captured like Crescent’s earlier prizes; the coming battle would be an even fight between two similarly sized, armed and manned frigates.

Fresh from its refit and sporting a clean bottom, Crescent was fast, and with the wind in its favor, it was only a matter of time before it caught its prey. The British frigate edged down on the fleeing Frenchman, seawater frothing along its sides, wind singing in the rigging, its men exchanging raptorial grins.

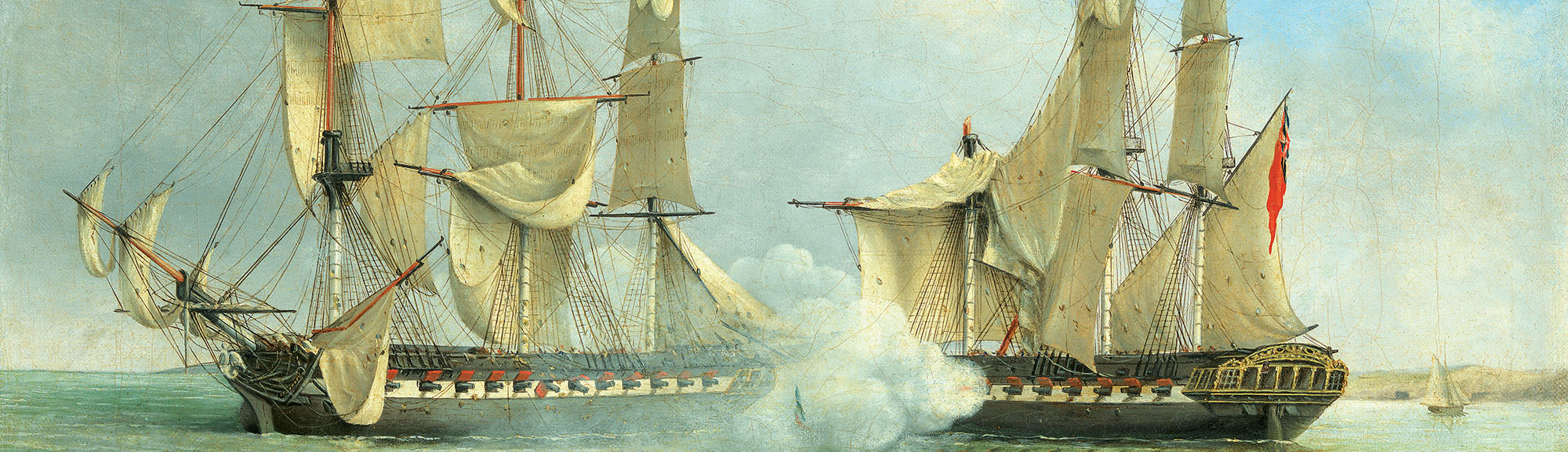

By half past 10 Crescent had closed on the enemy, which proved to be the 36-gun Réunion. From his position off the target’s port quarter, Saumarez had his gunners fire an opening broadside into his quarry. The boom of its guns resounded along the French coast some 5 miles distant, where spectators had gathered to watch the duel.

Midshipman John Tancock later recalled the men had orders to fire at Réunion’s rudder, while the French gunners were aiming high in an effort to dismast Crescent. Their respective fire took effect, soon cutting up the rigging and sails of both vessels. Despite losing his ship’s fore-topsail yard and fore-topmast, Saumarez was able to maneuver Crescent under Réunion’s stern on the starboard quarter, allowing the British gunners to rake the enemy vessel fore and aft with murderous effect. Seeing no colors flying on Réunion, Saumarez ordered his men to cease fire. But the colors had been shot away, not struck, and the French gunners soon opened a ragged broadside. Crescent’s gunners responded and “kept up so good a fire,” Saumarez later wrote, “that in a short time [the French] waved their colors and made signs from the gunwale with their hats that they had struck.”

The action—a decisive victory for both Crescent and the Royal Navy—had lasted two hours and 10 minutes.

As soon as Réunion surrendered, Saumarez sent Parker and a prize crew to take possession of the badly battered French vessel. Though Crescent had sustained damage to its rigging, the crew had suffered no direct combat casualties—Rye took a grazing wound to the head, the recoil of a gun had broken another sailor’s leg, and two others reported minor injuries. The butcher’s bill was considerably higher aboard Réunion, which reported 33 men killed and 48 wounded, though Crescent’s officers estimated as many as 120 casualties. Saumarez took the French vessel’s captain and first officer captive.

About four hours after the action HMS Circe arrived on scene. Saumarez sent over 120 French prisoners to that vessel and directed its captain to carry out Crescent’s original orders—to deliver packets to the Channel Islands and look into Saint-Malo. Crescent and Réunion then turned toward Portsmouth—and fame. Light winds and calms hampered the crippled ships’ passage, and not until October 22 did they appear off the Isle of Wight. Word quickly spread of the British victory, and when Crescent and its prize entered Portsmouth Harbor the following day, a throng of military personnel and other well-wishers cheered their arrival.

In its October 25 edition The Times of London reported the shattered condition of Réunion, observing that the French vessel’s sails were “so peppered that they can be converted to nothing but paper; the hull is much damaged; the ceiling of the wardroom, etc., entirely covered with blood, and the whole of the main deck has the appearance of a slaughterhouse shocking to look at.” In his official report, reprinted in The London Gazette on October 26, Saumarez praised his officers and men “for their cool and steady behavior during the action,” singling out “the three lieutenants, Messrs. Parker, Otter and Rye; their conduct has afforded me the utmost satisfaction.” The report confirmed the capture of Réunion “without the loss of a single man.”

Crescent’s victory over Réunion made overnight celebrities of the British frigate’s officers and men. Saumarez had won an engagement surpassing that of Captain Pellew in Nymphe, and he was duly rewarded. On October 30 First Lord of the Admiralty John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, presented the captain to King George III, who created Sir James Saumarez, Knight of the Bath. Crescent’s junior officers shared in the glory—Parker was given command of the armed sloop Albacore on the North Sea station, Otter was promoted to first lieutenant of Crescent, and Rye became second lieutenant.

Saumarez went on to a nearly uninterrupted series of successes. His coolness under fire again made headlines in June 1794 when he outfoxed a superior squadron of French ships by steering Crescent on a diversionary course before darting through a narrow, uncharted channel to safe anchorage off Guernsey, effecting his own escape and that of two other frigates under his command. The Admiralty rewarded Saumarez in 1795 with the command of HMS Orion, a 74-gun ship of the line, with many officers and men from Crescent following him aboard. Saumarez again distinguished himself in action against French and Spanish ships at the 1801 Battle of Algeciras and later served as commander in chief of Britain’s Baltic Fleet. He ultimately rose to the rank of admiral and in 1831 was elevated to the peerage as Baron de Saumarez.

Charles Otter did not enjoy the luck of his former commander. Although he attained post rank, he had the misfortune of losing his ship, the 32-gun frigate Proserpine, in an engagement with the French frigates Pénélope and Pauline off Toulon on Feb. 27, 1809. Otter was captured and imprisoned until the end of the war. An 1814 court-martial acquitted him for the loss of his ship, noting he had defended it “in the most gallant and determined manner…until resistance was of no avail.” Regardless, Otter thereafter dropped from the naval record.

Peter Rye fared considerably better. After following Saumarez to Orion and serving valiantly at the June 23, 1795, Battle of Groix off Brittany, he was appointed to command the armed cutter Earl Spencer. Later, as commander of the hired armed brig Providence, Rye was cited for his April 11, 1805, capture of the Dutch schooner L’Honneur and on another occasion for successfully fighting off five Danish gunboats while becalmed off Jutland. He again served under Saumarez in the Baltic, attained post rank in 1812 and later commanded the ships Ceylon and Porpoise. Rye retired as a rear admiral in 1846.

George Parker also had a highly successful career. While commanding the captured Spanish frigate HMS Santa Margarita, he took a number of prizes off Ireland and in the West Indies. On March 22, 1808, while commanding the 64-gun ship of the line Stately in company with the 64-gun Nassau, Parker forced the surrender of the 74-gun Danish ship of the line Prindts Christian Frederic. He later commanded the 74-gun Aboukir in the North Sea and in the Mediterranean. Parker was made a Knight Commander of the Bath in 1833 and promoted to admiral in 1837.

James Saumarez topped them all. Though beached for nearly a decade, when given the opportunity he proved himself a resourceful and bold frigate captain. He also proved a gifted leader of men, whose guidance and example propelled several of his junior officers to stellar careers of their own. A nation can ask little more of those who willingly go to sea and put themselves in harm’s way for the greater good.

U.S. Navy Reserve Captain Scott Rye is chief of staff for Navy Reserve Public Affairs and the author of Men and Ships of the Civil War and Of Men and Ships: The Best Sea Tales. For further reading he recommends Memoirs and Correspondence of Admiral Lord de Saumarez, by Sir John Ross. Also visit the Sausmarez Manor website [sausmarezmanor.co.uk].

First published in Military History Magazine’s November 2016 issue.