Centuries before the great sea battles of Trafalgar, Jutland, Midway and Leyte Gulf a momentous naval engagement temporarily united Christendom and ended Muslim domination of the Mediterranean Sea. A turning point in naval history, the 1571 Battle of Lepanto was waged across a 5-mile front in the Gulf of Patras, west of the Ottoman-held Greek port of Lepanto (present-day Nafpaktos). The furious and sanguineous encounter pitted the fleet of Pope Pius V’s Holy League against a superior Turkish armada under Ottoman Grand Admiral Ali Pasha. As decisive as it proved on a strategic level, Lepanto marked the swan song of the war galley, as the sailing vessels that fought alongside their oar-powered sisters were the wave of the future.

Late 16th century Europe was rent by political and religious divisions. With the dissolution of the Roman empire and the coming of the Reformation, Christendom—once centered on the Roman Catholic Church—had fractured into conflicting states and denominations. By contrast, the Islamic world was under the dominion of the Ottoman empire, then at the peak of its strength.

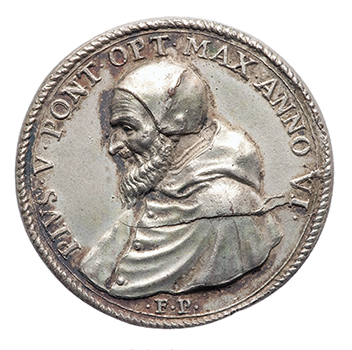

Early that century the Turks probed Europe’s eastern frontiers. After ransacking much of the Balkans, the Muslims threatened Vienna and seized then separate Buda and Pest. Ottoman galleys raided the coasts of Italy, Syria, Egypt and Tunisia, captured Rhodes, besieged Malta and invaded Cyprus. Finally, after an appeal by the Venetian Senate, Pius V started organizing resistance to the Muslim empire. On March 7, 1571, the pontiff sponsored creation of the Holy League, comprising the papal states, Spain, Venice, Genoa, Tuscany, Savoy, Urbino, Parma and the Knights of Malta. Though its formation came too late to forestall the Ottoman capture of Cyprus, that spring Pius ordered its combined fleet to sail for Greece and seek out the Turkish armada, reportedly holed up at Lepanto.

Following up on Ottoman gains in the Mediterranean, Sultan Selim II was assembling the men, ships and materiel necessary to sack Rome. The Urbs Aeterna (“Eternal City”) was viewed as ripe for plunder. The pope feared that if Rome fell, the rest of Europe would surely follow. Regardless, Portugal and the Holy Roman empire (Germany, Italy, Burgundy and Bohemia) shunned the pontiff’s alliance, while distant England and France showed no interest in opposing the Turks. Though chronically at odds, Venice and Spain were the two leading Christian naval powers in the Mediterranean.

Answering the papal summons, the member states of the Holy League dispatched fleets, which assembled in the harbor at Messina, Sicily. The commander of the armada was 24-year-old John of Austria, the illegitimate son of Spanish king and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and German singer Barbara Blomberg. At the time of the invasion John’s half brother ruled Spain as Philip II. The pope had picked the blue-eyed, fair-haired “crownless prince” to lead the often fractious league because he sensed John was, as historian Jack Beeching put it, “someone who in council would rise above pettiness and envy, who in battle would lead without flinching.” A gallant campaigner on both land and sea, John had put down a bloody 1568–70 uprising by Christianized Moors in the Spanish Albujerras. That said, he now faced a far more formidable opponent.

“Charles V gave you life,” Pius told John upon the latter’s commissioning. “I will give you honor and greatness.”

All that summer of 1571 the Christian fleet made its preparations at Messina. It mustered 206 galleys—long, flat-bottomed craft each mounting a projecting bow spur designed to ride over and break an enemy vessel’s oars. The larger galleys carried cannons in their bows. Venice furnished 109 galleys, Spain 49, Genoa 27, the papal states seven, Tuscany five, and Savoy and the Knights of Malta three each. Privately owned ships in the Spanish service rounded out the galleys. The Venetians also provided six sluggish floating fortresses known as galleasses. Steep-sided, 160 feet long and powered by 50 oars, each carried a contingent of musketeers and/or bowmen and upward of 30 cannons. Venetian, Spanish, Genoese, Portuguese and papal crews manned 76 smaller vessels.

John had about 80,000 men under his command, including nearly 50,000 seamen and oarsmen and 30,000 troops, two-thirds of whom were in Spanish service. The soldiers wore light armor and carried swords. Each was armed with a bow, a harquebus or the latter’s heavier variant, the musket. Manning the oars were mercenaries, Muslim captives and convicts promised release on victory.

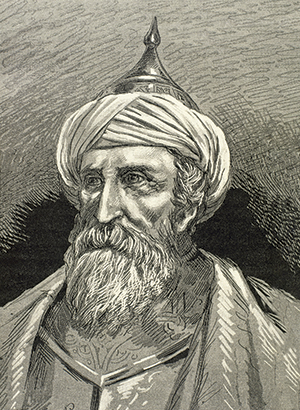

Ali Pasha’s larger Ottoman fleet comprised 222 galleys, more than 50 swift galliots (small oared vessels) and a number of smaller vessels. Aboard were some 50,000 seamen and oarsmen and more than 34,000 soldiers. Some 15,000 of the oarsmen were Christians captured at sea or during shore raids. They, too, had a chance at freedom—were John’s fleet victorious. Among the Turkish troops were elite contingents of plumed, booted slaves known as Janissaries. Selected in childhood from among Christian prisoners, these Islamic converts were armed with bows, short sabers and harquebuses. Established in the 14th century, the Janissary corps represented modern Europe’s first standing infantry.

By mid-September the Holy League fleet was ready to sail from Messina. Pius V sent John a papal legate to bless the fleet and a standard to fly from the masthead of the admiral’s flagship, Real. Sporting a blue background, the woven ensign depicted the crucified Jesus Christ supported by the coats of arms of the Holy League members. The Spanish ships bore the coats of arms of Aragon and Castile, while the Venetian craft each displayed the winged Lion of St. Mark, symbolizing the patron saint of Venice.

Assigned to the papal galleys were 30 cross-bearing Capuchin friars. The perceptive pontiff believed his seamen and soldiers would fight bravely if chaplains went into battle beside them. Leading the friars was Father Anselm of Pietramolara, a venturesome former cavalryman. Other fleet padres included a half dozen Jesuits aboard the Spanish vessels and a scattering of Dominicans and Theatines.

The Turkish sailors and soldiers sought to intimidate their foe with defiant yells, shots and clashing gongs. Amid the clamor the Holy League vessels held their fire, and an ominous silence followed as the armadas closed on one another

At dawn on September 16, despite the risk of seasonal storms, the fleet weighed anchor and eased out of Messina harbor, John’s flagship leading the way. Standing on the end of the jetty, surrounded by robed clergy, the papal legate blessed each passing vessel. By midmorning the Strait of Messina was filled with billowing sails and fluttering pennants as the armada set a course to round the Calabrian “toe” of the Italian peninsula and continue on a northeasterly bearing.

Three days later, while the fleet sheltered from a storm at the entrance to the Gulf of Taranto, its commanders received a disquieting report. It seemed the Turkish fleet was dispersing and might never confront them. That night, however, a meteor flashed across the sky, lighting up the surface of the sea before bursting into three fading trails. The Christian admirals took it as a hopeful portent.

On September 24, after clearing the peninsular “heel” of Salento, John’s ships steered eastward across the churning mouth of the Adriatic Sea toward the Greek island of Corfu. New missives brought word the Ottoman fleet had not dispersed, but had raided Corfu and was headed back to port at Lepanto. Regardless, stormy weather forced the Christian fleet to shelter in the lee of the islands off northwestern Greece. When the skies cleared, they sailed into Corfu harbor. Going ashore to forage for food and water, soldiers discovered the Turks had plundered local villages and desecrated their churches. Before leaving harbor, the fleet commanders embarked 4,000 troops from the Corfu garrison and gathered in formal council one last time.

Weighing anchor, the Christian armada sailed southward against strong headwinds toward the Gulf of Patras. At the back of the gulf lay a connecting strait to the Gulf of Lepanto guarded by the namesake fortified harbor of Lepanto. There, while the Turkish fleet rested and reprovisioned, Ali Pasha and his commanders debated the best course of action. Meanwhile, winds and heavy fog again forced John’s fleet to hole up, this time in a protected harbor just outside the Gulf of Patras. On the evening of October 5 a Turkish informant—likely a double agent—reported to Christian commanders that the Ottoman force had been reduced to 100 galleys, its sailors stricken by a plague. In fact, within 24 hours the enemy fleet would venture out from Lepanto in search of battle.

At 2 a.m. on Sunday morning October 7, the Holy League fleet weighed anchor once more and threaded its way south between the islets and shoals of western Greece. The sea was choppy, and a southwesterly wind blew in the faces of John’s seamen.

As dawn broke and the Christian vanguard rounded the mouth of the Gulf of Patras, John asked that Mass be celebrated throughout the fleet. Before the priests had finished granting the sailors and soldiers absolution, watchmen in Real’s maintop sighted two distant sails, soon four, then eight. Within minutes the entire Turkish armada—hurried westward by a favorable wind—was visible on the horizon, bearing down on the Christian fleet.

Clambering over the side of his flagship into a light galley, John sailed across the line of 64 ships in his center squadron to encourage his seamen and soldiers. “My children, you have come to fight the battle of the cross—to conquer or to die!” he cried out while holding aloft a crucifix. “But whether you are to die or conquer, do your duty this day, and you will secure a glorious immortality!” He then returned to Real. Powered by 70 oars and manned by 400 oarsmen and an equal number of troops, his flagship was at the heart of the Christian battle line. Kneeling at its bow, the commander prayed for victory, while officers and men across the fleet did the same. Aboard the dozen papal galleys Capuchin friars moved among the tense oarsmen and soldiers, promising each man a plenary indulgence from the pope in exchange for fighting for the faith. Each Christian had been handed a rosary before leaving Messina.

The Turkish battle line was 3,000 feet longer than that of the Christians and spanned the entrance to the gulf. John’s force faced a further disadvantage as it struggled through mist and stiff headwinds. The Turkish sailors and soldiers sought to intimidate their foe with defiant yells, shots and clashing gongs. Amid the clamor the Holy League vessels held their fire, and an ominous silence followed as the armadas closed on one another.

Onetime cavalryman Father Anselm grew alarmed, realizing that in terms of strength and numbers he and his fellow Christians faced a real danger of defeat. Clutching his crucifix, he prayed to the Virgin Mary, beseeching her to intercede. According to the chronicler Boverius, the Madonna suddenly appeared in the sky above John’s fleet, gazed down with kindly eyes and blessed it. At that moment the wind shifted in the Christians’ favor.

Both sides relied on the slave labor of galley oarsmen to keep their ships in motion. Chained to benches belowdecks in filthy, close-quarters conditions, they could expect slow death from either disease or beatings but faced immediate death were the galleys to sink. As the Muslim fleet lost momentum on a waning breeze, galley masters whipped their oarsmen into action. Meanwhile, John reportedly ordered galley slaves and convicts throughout the Christian fleet unshackled and issued swords or pikes to use in the anticipated ship-to-ship fighting.

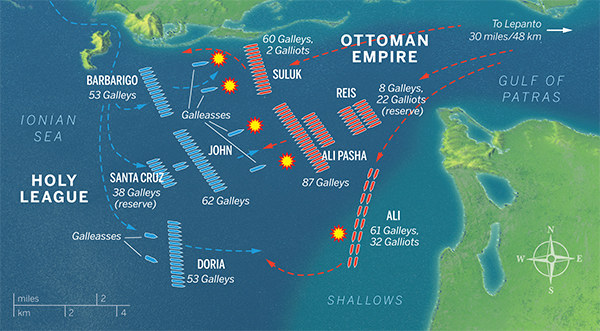

Along John’s battle line crewmen shook out lateen sails that quickly filled. On the Christian left were 53 galleys under Agostino Barbarigo, a soft-spoken and popular Venetian admiral. Leading from the center was John, supported by the able papal commander Marco Antonio Colonna and 75-year-old Venetian admiral Sebastiano Venier, a scarred veteran warrior. Following directly astern were the 38 galleys of the reserve squadron led by Spanish admiral Álvaro de Bazán, the Marquess of Santa Cruz. Commanding 53 galleys on the Christian right was Giovanni Andrea Doria, great-nephew of the legendary Genoese admiral Andrea Doria.

Before them the Muslim fleet stretched from coast to coast, with Ali Pasha’s flagship Sultana front and center, directly opposite John’s Real. Each Ottoman squadron comprised some 60 galleys, while a smaller reserve brought up the rear.

As at the 31 BC Battle of Actium—fought scarcely 50 miles to the north, albeit 16 centuries earlier—the opposing fleets were arrayed three squadrons abreast, the vessels in each group also in line abreast. Thus the armadas drew together.

Although naval convention precluded flagships from engaging an enemy, Real and Sultana unflinchingly led from the center. While still several miles distant, the Turkish flagship fired a gun in salute, breaking the silence. A gun aboard Real answered. A second Turkish shot echoed, and another Christian cannon replied. The battle lines slowly rowed together until about 500 yards apart and then burst forward to engage.

At that very hour, period chroniclers write, Pius V was conferring with financial advisers at the Vatican when suddenly the pontiff stopped, opened a window and stared at the sky. “This is no time for business,” he told his treasurer. “Go and give thanks to God, for our fleet is about to meet the Turks, and God will give us the victory.” Pius then knelt in prayer.

More than 500 miles to the southeast in the Gulf of Patras the Christians hoped to shatter the Ottoman line with their big galleasses, while the Turks, fearing their light galleys would be mauled in a head-on confrontation, planned to outflank the Christian right and left, then fall on John’s fleet from the rear.

Bristling with guns but too heavy to maneuver swiftly, four of the six Venetian galleasses had been towed by galleys to fixed positions 1,000 yards forward of the Christian right and center. The two on the right could not be deployed in time for the opening cannonades, which resounded across the gulf around noon. Wherever the advancing Turks were forced to maneuver around the galleasses, they took severe losses from the big ships’ broadsides. The floating bastions did break the enemy lines, but not decisively. Thirty minutes later ship-to-ship skirmishes erupted as the opposing fleets, each stretched out some 5 miles, swung together.

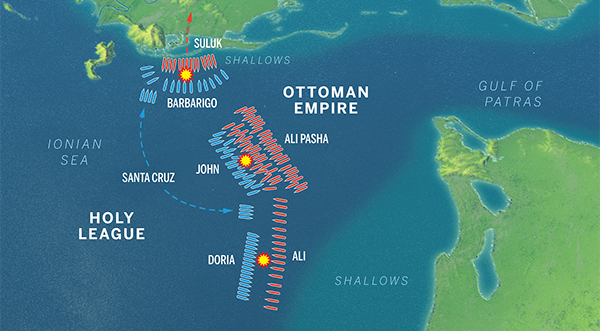

On the right of the Christian line the overcautious Doria was nearly outflanked in the gap that had opened between his squadron and the center. But his galleys and those of the reserve combined to deliver devastating fire at the waterline of enemy vessels, sinking some with a single volley. Meanwhile, on the left Barbarigo’s galleys took the fight into the very shallows to thwart Turkish attempts to outflank them. On lifting his visor to be better heard, the Venetian commander was mortally wounded by an arrow to the left eye. By 1 p.m. the main bodies of the opposing armadas were fully engaged. Galley bow guns boomed, and the air filled with smoke, flame and the shouts and screams of fighting and dying men.

The battle became a general melee as galleys rammed one another and boarding parties struggled with opposing crews on slippery, bloody decks. The confused action raged for hours. The Holy League ships poured cannon fire into the Turkish galleys at point-blank range. The accompanying volleys of the harquebusiers and musketeers were particularly devastating, clearing the fighting decks of many an Ottoman vessel before they could be boarded.

The hottest fighting raged between the opposing flagships as Sultana, carrying 300 Janissary harquebusiers and 100 archers, bore down on Real. Ottoman gunners shredded the Christian flagship’s rigging, and Turkish soldiers twice sought to board Real. The tide finally shifted when Colonna’s galley, Capitana, rammed Sultana, his harquebusiers raking the enemy flagship’s deck with murderous fire. Struck in the forehead by a round, Ali Pasha dropped where he stood. Moments later men from both Real and Capitana swarmed aboard the Turkish flagship and captured it, replacing the Muslim standard with the banner of Christ. The boarders soon subdued the rest of Sultana’s crew. One of John’s saltier sailors severed Ali Pasha’s head, jumped overboard and swam over to Real to present it to the admiral. The grisly trophy briefly sat atop a pike at the Christian flagship’s stern before some merciful soul tossed it into the sea.

The Holy League chaplains were in the thick of the fighting—holding crucifixes high in encouragement, comforting the wounded and praying for the dying. One Italian friar clung to the pinnacle of a topmast jubilantly shouting, “Vittoria, Vittoria!” When a group of Turks boarded Father Anselm’s galley, the former cavalryman grabbed a sword from a fallen Muslim and started swinging. Before he realized what he was doing, seven enemy soldiers lay dead at his feet. Inspired at the sight, Anselm’s fellow Christians drove the rest of the Turks from the galley.

Among the many Christian heroes at Lepanto was a 24-year-old Spanish common soldier who would gain fame as an author. Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra served on the Christian right aboard Doria’s Marchesa, which saw much action. Although feverish with malaria, Cervantes wielded a sword and was among the first of his squadron to board one of the Turkish galleys. He suffered three gunshot wounds, one of which maimed his left hand—“for the glory of the right,” quipped the future Don Quixote novelist.

After running out of cannon balls, shot and arrows, the exhausted Muslim crews pelted the Christians with oranges and lemons. John’s men tossed them back with laughter

Another Spanish hero of the battle was a harquebusier aboard the flagship Real who turned out to be a young woman in disguise. María la Bailadora (“The Dancer”) had joined the expedition so as not to be parted from her officer lover. As grappling irons held Real and Sultana fast, and a boarding party scrambled aboard the latter, María reportedly leaped nimbly to the deck of the enemy ship and killed a Turk with a single sword thrust. She was rewarded by being allowed to remain in the pay of her regiment.

Standing by Real’s mainmast beneath the Holy League banner, John made a conspicuous target. Though aides begged him to go belowdecks, he refused. Also fighting from the front was Venier, whose Capitana was also locked in combat with Sultana. As orders were pointless in the noise and confusion, Venier simply stood at his prow and fired into the enemy ranks with a blunderbuss while a servant reloaded his weapon. The venerable admiral “performed the feats of arms of a young man,” reported a contemporary chronicler.

By 2 p.m., with Ali Pasha dead and his flagship gutted, the Ottoman fleet was reeling. Adding insult to injury, Christian boarders deep in Sultana’s hold discovered and confiscated the Turkish commander’s personal fortune of 150,000 Venetian gold sequins, which he’d unwisely chosen not to leave in Constantinople.

The skill of John’s seamen and superior firepower of his soldiers put the Turks to flight, those trapped against the shore by ships on the Christian left being put to death by the thousands. The few Ottoman galleys still putting up a fight in the center were destroyed. After running out of cannon balls, shot and arrows, their exhausted crews pelted the Christians with oranges and lemons. John’s men tossed them back with laughter.

When the battle ended at 4 p.m., the Gulf of Patras was red with blood and strewn with broken ships, bodies and debris. That night the Holy League fleet retired to an anchorage just outside the gulf, while a few burning hulks flared on the darkened sea.

Losses on either side were terrible. Sixty Ottoman galleys went aground, 53 were sunk or destroyed, and 117 galleys and 20 galliots were captured. Some 30,000 Turks either drowned or were killed in battle. The Holy League fleet lost 13 galleys, 7,600 men killed and almost 8,000 wounded. Freed in the wake of the victory, however, were most of the 15,000 Christian slaves who had manned the oars of the enemy galleys.

When news of the victory reached Rome, it was attributed to the intercession of the Virgin Mary, and Pius V burst into tears of joy. Though his prestige soared, the pope gave all credit to his adept admiral. “There was a man sent from God whose name was John,” he said, echoing the scriptural reference to John the Baptist.

For the first time in memory the Turks had been beaten decisively, and a wave of relief and renewed confidence surged across Christian Europe. Church bells pealed, bonfires blazed in Venice, Christian poets churned out verses and mints struck commemorative coins.

Lepanto, the last great battle of the last crusade, was both decisive and indecisive. The Christians ended Turkish domination of the Mediterranean, but Pius V died the following spring, and his Holy League soon disintegrated, failing to follow its naval triumph with a coordinated resistance on land. The Turks held on to Cyprus, Muslim warships continued their depredations, and the Barbary pirates of North Africa continued to prey on Western shipping for centuries.

Lepanto marked the last major instance of naval warfare as an extension of ground warfare, with soldiers fighting on the high seas. It also brought the Age of Sail to fruition. The sailing vessels deployed in battle off Lepanto were speedier than the galleys, boasted more offensive capacity and were more seaworthy. Combat at sea would never be the same. Cannons and sails steadily replaced swords and oars, and a mere 17 years later Queen Elizabeth’s Royal Navy defeated brother-in-law Philip II’s Spanish Armada. MH

The late newspaperman and author Michael D. Hull was a longtime and frequent contributor to Historynet magazines. For further reading the editors recommend The Venetians, by Colin Thubron; Lepanto, 1571, by Angus Konstam; 100 Decisive Battles, by Paul K. Davis; and Sea Power, edited by E.B. Potter.

This article appeared in the November 2021 issue of Military History. For more stories, subscribe and visit us on Facebook.