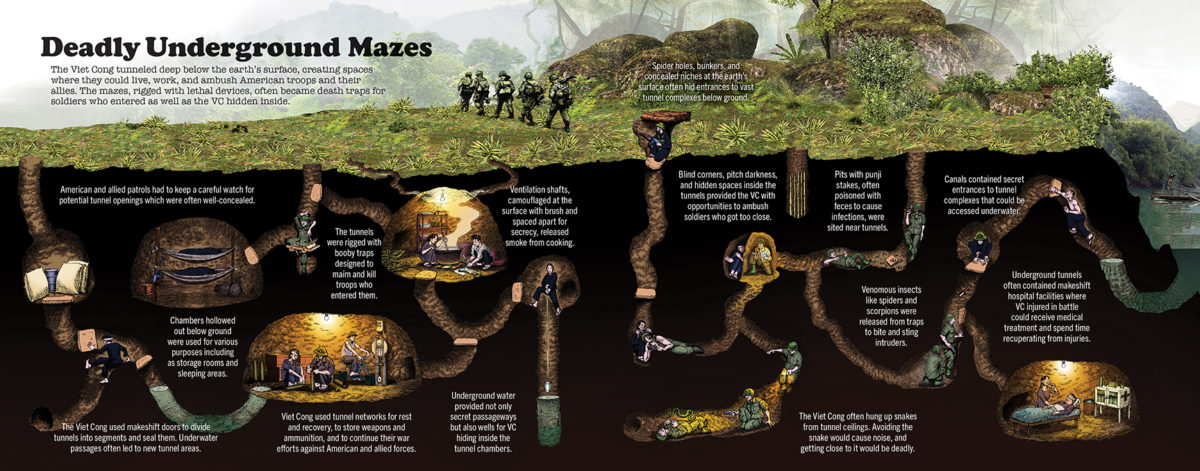

The Viet Cong were well known for their devious jungle ambushes and cruelly ingenious booby traps. But one of the enemy’s deadliest—and stealthiest—techniques was to burrow in underground tunnels deep beneath the earth’s surface and launch attacks from the cover of dark and labyrinthine caverns.

The Americans and their allies who took on the gruesome task of rooting out and defeating these hidden foes earned the humble but proud nickname of “tunnel rats.” Yet, in their first large-scale encounter with underground enemies at Cu Chi, the “tunnel rats” and their fellow soldiers were far from prepared for the horrifying dangers that lurked below them.

Operation Crimp

Operation Crimp, undertaken by U.S. and Australian forces in Binh Duong Province, South Vietnam, from Jan. 8-14, 1966, was the largest search and destroy action during the Vietnam War for its time. Maj. Gen. Jonathan O. Seaman, commander, 1st Infantry Division, was the overall allied leader. Combat units included 8,000 soldiers from the 1st Infantry Division, composed mainly of troops from the 1st Infantry Division’s 173rd Airborne Brigade and the 3rd Brigade. The 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, operating as part of the 173rd, played a significant role in the operation.

The mission, according to the After-Action Report written by Col. William D. Brodbeck, commander of 3rd Brigade, and staff member 2nd Lt. Leo J. Mercier, was to “strike at the very heart of the Viet Cong [VC] machine in Southern RVN [Republic of Vietnam], the notorious ‘Hobo Woods’ Region in Binh Duong Province, just West of the fabled ‘Iron Triangle’ believed to be the…headquarters of the Viet Cong Military Region 4” (within the area U.S. forces designated the III Corps Tactical Zone).

Unsuspecting U.S. and Australian forces would literally step onto a formidable tunnel network, which extended more than 150 miles from the outskirts of Saigon all the way to the Cambodian border. The communists began digging these tunnels under the jungles of South Vietnam in the late 1940s while fighting the French. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, communist rebels used them to hide from the better equipped Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). They hollowed out hundreds of miles of subterranean passages throughout South Vietnam bit by bit and often by hand.

Hidden Tunnel Networks

These tunnels were able to withstand most explosions—the soil contained clay and iron which created a cement-like binding agent. Young “volunteers” dug the tunnels in the monsoon season when the soil was soft. As soil dried, it remained stable without supports.

Communist soldiers used the underground caverns to house troops, store and transport supplies, and initiate surprise attacks. After launching savage attacks against U.S. and allied forces, these fighters would disappear at will into subterranean sanctuaries. Enemy troops spent most of their time underground in areas where heavy artillery shelling occurred.

One U.S. report indicated that enemy tunnel systems contained “living quarters, kitchens, ordnance factories, hospitals, and bomb shelters. Some even had theaters and music halls.” The Cu Chi tunnels could house entire villages.

Operation Crimp’s search and destroy mission was one in a series of operations beginning after the U.S. troop buildup in 1965. At first the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), commanded by Gen. William C. Westmoreland, followed a policy of building defensive positions around Saigon. Eventually the general convinced leaders in Washington to go on the offensive. He hoped search and destroy operations would force the enemy into conventional battles that would drain them of men and materiel.

Enter the Aussies

Australia first sent advisers to Vietnam in 1963. In June 1965, they deployed 1,400 members of the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (1/RAR), commanded by Lt. Col. Ivan “Lou” Brumfield. These forces, as well as New Zealand units, were placed under the operational control of U.S. Brig. Gen. Ellis W. Williamson of the 173rd Airborne Brigade.

The men of 1/RAR participated from the start in airmobile operations with the 173rd Airborne Brigade, using helicopters to ride into battle. They could quickly insert infantry and artillery wherever needed, while helicopters provided fire support, casualty evacuation, and resupply. The 1/RAR played a role in several operations in War Zone D, targeting communist bases in the so-called “Iron Triangle.” By Jan. 1, 1966, the Australians, now led by Lt. Col. Alex Preece, had become a respected part of the 173rd.

If they had decided to go ahead with their original plan, troops would have landed right on top of a hidden enemy position.

Plans called for Operation Crimp to begin on the heels of Operation Marauder with preparatory action to commence late on Jan. 7, 1966. The actual deployment of troops was to begin at 5:30 a.m. the following day. The Number 105 Field Battery, Royal Australian Artillery was to provide artillery support. The engineers from No. 3 Field Troop, Royal Australian Engineers, and the M113 armored personnel carriers from the Prince of Wales’ Light Horse also provided support.

Once artillery shelling and airstrikes ended, the 173rd was supposed to initiate an airmobile attack from both the north and west, while the 3rd Brigade sealed off the area to the south, in preparation for a sweep designed to force enemy combatants to flee east toward the Saigon River where they would be annihilated. The Aussies were to hold the brigade’s northern flank.

Subsequent historical reports stated that Crimp was intended to be “controlled by the 1st Infantry Division, which employed the 3rd Brigade to the south of the 173rd Brigade AO [area of operations]. Actions to be conducted within the 173rd AO were left to the discretion of Brig. Gen. Williamson to best accomplish the mission of driving into the ‘Ho Bo’ Woods region to destroy the headquarters of Military Region Four.”

Only hours before the attack, the 1/RAR’s Operations Officer, Maj. John Essex-Clarke, effected an aerial reconnaissance over their landing area. Observing a lack of ground cover, he speculated there might be an extensive VC defense position nearby. Commanders opted to land at a less exposed location. If they had decided to go ahead with their original plan, the Australian troops would have landed right on top of a hidden enemy position. The commander of the No. 3 Field Troop forces, Capt. (later Col.) Alexander Hugh “Sandy” MacGregor, later declared that the “decision almost certainly saved hundreds of Australian lives.”

Hidden in this dense jungle area of the Ho Bo Woods was the headquarters of the enemy’s Fourth Military Region directing hostile activities in and around Saigon. Throughout the planning stages, intelligence from allied moles, enemy prisoners, and aerial reconnaissance indicated that this vital enemy epicenter was somewhere within a 12-square-mile area of jungle and marshland. The communist base had four entrances, each protected by VC Regional Force troops. Planners believed that two VC Main Force battalions (5,000 men) were also in the region, made up of the C306 Local Force Company, 3rd Quyet Thang Battalion, and 7th Cu Chi Battalion. Yet the planners had no idea what ghastly surprises awaited their troops below ground.

Stumbling Across the Tunnels

Nothing seemed “off” at first as the battle began as intended. Concentrated artillery fire was followed by tactical air assets dropping napalm to defoliate the attack zone. The U.S. Air Force then flew B-52 Arc Light airstrikes which “caused considerable damage” to enemy defenses. Airmobile forces struck around 9:30 a.m. Col. Brodbeck’s 3rd Brigade landed on the northern, western, and southern ends of the battle area. Two more battalions landed southwest. The remainder arrived overland as part of a convoy. Some blocked the south end of the Ho Bo Woods. Others swept the area to their front. Enemy snipers and small units targeted these forces.

Along the northern perimeter, Australian troops disembarked at Landing Zone March about two miles south and west of the American troops. The Aussies fought a path through a grisly maze of bunkers, punji stakes, and booby traps to reach their position.

The VC had seeded the entire area with tripwires attached to artillery shells and grenades rigged in the undergrowth or hanging from tree branches. In addition to these hellish circumstances, the Australians were also misidentified by a U.S. helicopter that fired on them. Fortunately, they contacted the Americans and were able to avert total disaster.

The enemy fired from a nearby tree line as D Company, 1/RAR, commanded by Maj. Ian Fisher, approached the clearing that was originally supposed to have been their landing area. Six men of the 12th Platoon were wounded, including their commander Lt. James Bourke. Two medics attending the wounded were killed. Col. Preece ordered his remaining companies to circle the flanks of D Company to block the enemy and take up their planned position. They were also fired on. The enemy popped up from behind trees, ditches…and what proved to be hidden tunnel entrances.

Preece soon came to a terrifying realization—the Australians had stumbled onto a massive enemy defensive position located primarily underground. Sure enough, Maj. Ian McFarlane’s B Company soon pinpointed an underground enemy hospital. The subterranean nest was complete with medical supplies, rudimentary transfusion equipment, and important military documents. But the Australians had not touched on the true extent of the underground labyrinth yet. Worse was yet to come.

The U.S. 1st Battalion, 503rd Infantry Regiment, of the 173rd Airborne Brigade was inserted at LZ April around noon, while the 2nd Battalion put down at LZ May at 2:30 p.m. With the deployment going as planned, the brigades marched eastward and converged at what operatives believed was the location of the communists’ Military Region Four headquarters. Despite an exhaustive search, they failed to find much of value.

Enemies Under the Ground

Leaders speculated that the enemy had fled in the face of the initial allied advance. As it turned out, the 7th Cu Chi Battalion had withdrawn north and the 3rd Quyet Thang Battalion to the east. To the south, the 3rd Infantry Brigade moved slowly as the enemy staged numerous hit-and-run ambushes to distract the Americans from their secret underground mazes.

Nightfall approached. Concerned about an ambush, Preece drew his units into a tight perimeter. Soon, the Australians detected movement along C Company’s perimeter. A squad of VC was trying to infiltrate their position. At first, sentries thought it was one of their own patrols, and as a result Australian machine gunners did not open fire until the last second. One infiltrator was killed and the others fled. Similar events continued throughout the night. Undetected communist forces seemingly sprang up out of nowhere and appeared to vanish into thin air after withdrawing.

It soon became obvious to the Australians that these enemies were lurking below ground. Preece reasoned the entire area was honeycombed with tunnels, which the VC were using for rapid movement and concealment. Brodbeck and Preece concluded that the Australians were located in the very midst of the enemy forces. Several minor firefights erupted the next morning—but 1/RAR decided not to use their machine guns to avoid revealing their positions in the dark or hitting friendly troops. They resorted to throwing grenades forward of the perimeter.

The “Tunnel Rats” Go In

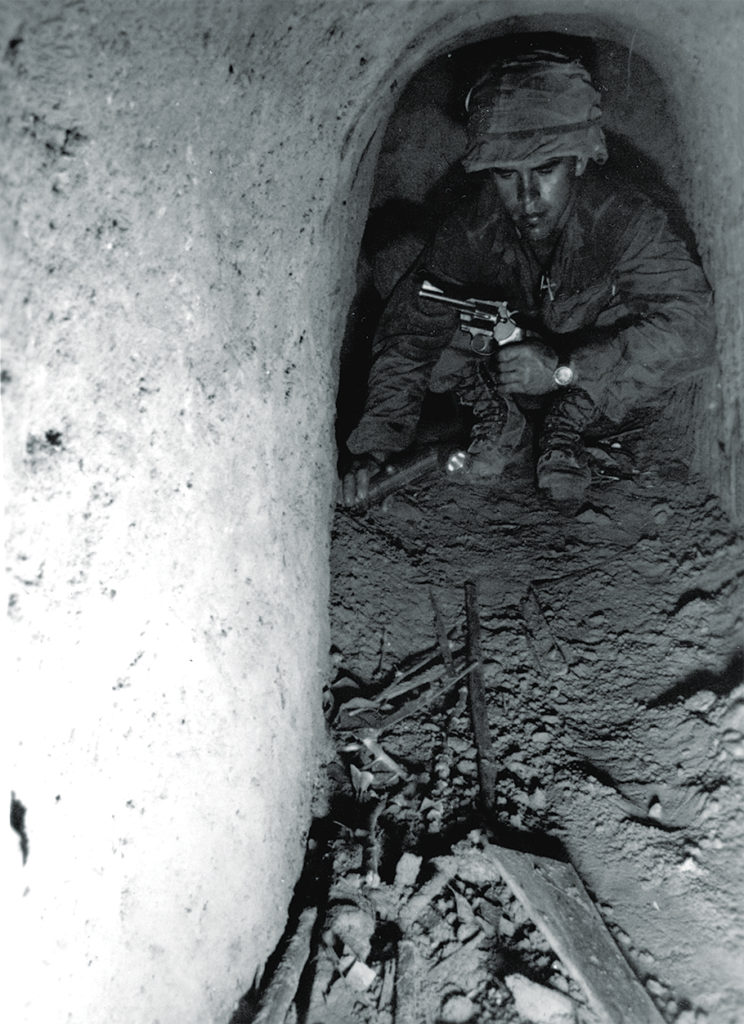

Searches of the tunnels began on Jan. 9. The aim was to destroy enemy stashes and soldiers and to demolish as many tunnels as possible. A stalwart group of soldiers known as “tunnel rats” would crawl through the caverns to eliminate enemy combatants and destroy their safe havens. The soldiers assigned to search the Cu Chi tunnels described them as “eerie and dark” and having a “black echo.” Many of these secret passageways were accessible only via claustrophobic crawlspaces protected by booby traps.

While Australian teams were originally called “ferrets,” eventually anyone brave or crazy enough to perform such duties became a “tunnel rat.” These resilient men entered the tunnels through extremely tight openings. Equipped with pistols, grenades, and flashlights, they crept into cave areas where few, even if they had been able to fit inside, would dare to go.

Out of necessity, the tunnel rats tended to be smaller and thinner men with nerves of steel. Once inside the main passageways, they would often plant explosives to destroy the tunnels—suffocating the Viet Cong and sealing them inside their pitch-dark caverns forever.

The Americans and the Australians took different approaches to “tunnel rat” work. Based on tactics derived from World War II, Americans often either sealed, blew up, or poured smoke, tear gas, or napalm into the tunnels to render them unusable. The Australians instead tended to have their military engineers search and map the tunnel complexes they located.

“Black Echo”

Capt. MacGregor led the Australian sappers of the No. 3 Field Troop in systematically exploring and clearing the tunnels in their area. They employed telephone lines and compasses to traverse the subterranean passages. The tangled web of tunnels was replete with command, control, and communications nodes as well as medical and living facilities. The enemy sited weapons in larger spaces connecting the tunnels on opposite sides to destroy intruders with crossfire. Some tunnels were 500 yards long.

The passageways formed mazes with several ancillary tunnels jutting off from the main passageways. In some places, the shafts were one, two, and even three levels deep. One report described the tunnel network “as so extensive they could house 5,000 men, some of whom lived underground, on and off, for as many as six months at a time.” On seeing the tunnels, one U.S. soldier said they were like “the New York subway.”

Over the next few days, Australians seized 59 crew-served weapons, 20,000 rounds of ammunition, 100 fragmentation grenades, one 57mm recoilless rifle, explosives, clothing, and medical supplies. They reported 11 VC killed. Night engagements continued as the enemy sought to avoid a set piece battle. Five more communists were killed just outside their perimeter.

Americans supported by Australians from the Prince of Wales’ Light Horse engaged numerous enemy units, at one point confronting a sizeable enemy force in trenches to their front. Afterward, they found 16 bodies and evidence of 60 more killed. For his courage and daring, MacGregor later received the Military Cross.

An Underground Gun Battle

As the 3rd Brigade explored one tunnel complex, they engaged in a fight marked by intense hand-to-hand combat. According to Patricia Sullivan’s 2008 Washington Post article on the campaign, Lt. Col. Robert Haldane, commander of the 28th Infantry’s battalion in this action, rushed an enemy position while under heavy fire armed only with a pistol in order to give first aid to a number of wounded soldiers. His bravery inspired his men not only to save their companions but to accomplish their objective. Haldane later received the Silver Star.

On Jan. 11, soon after the 3rd Brigade resumed their advance, Stewart Green, a lean 130-pound sergeant of the 1st Battalion, 28th Infantry, inadvertently sat down on a nail. Not only did this cause a nasty shock and painful wound, but the nail actually proved to be the opening to a trap door leading into an enemy tunnel. Smarting from his wound, Green volunteered to crawl through the opening to get underground and investigate. He and a squad equipped with flashlights, pistols, and a field telephone crept down nearly a mile into the network of caverns.

Eventually they came upon an underground dispensary with 30 Viet Cong inside. A firefight ensued below the earth. Some of the startled enemy scurried out of an escape hatch. Others fired on the intruders. Wearing gas masks, the Americans hurled teargas grenades at the enemy and began fighting their way back to the tunnel entrance in what must have been a truly hellish underground engagement.

At one point, Green heroically crawled back to save a comrade. Once he had him in tow, both clawed their way out of the tunnel. When Green reported what happened to his superiors, they decided to use a smoke machine to blow smoke into the tunnel system. The ploy worked. The rising smoke exposed several tunnel entrances, various underground levels, and several bunkers. The Americans were stunned by the vast expanse of the network.

Changing Tactics

Tragedy struck on the afternoon of the 12th. An Australian engineer became wedged in a trap door between two underground rooms. Although they tried desperately, his comrades could not pry him loose. He suffocated to death from a combination of tear gas and carbon monoxide when he removed his respirator in his struggle to get free. The gruesome manner of his death and the failed rescue attempts left a pall of grief over the operation.

As casualties mounted, leaders took fewer risks. Instead of making further attempts to map tunnel networks, the Aussies began changing tactics—whenever they came upon VC who refused to surrender, the Australians would extricate themselves from the tunnel, blow it up, and seal the enemy below.

On Jan. 14, 1st Infantry Division commander Seaman realized they lacked the resources and manpower to totally explore and destroy the entire tunnel complex. Six days after Operation Crimp commenced, allied forces withdrew and the operation ended. The Australians alone had unearthed an excess of 10 miles of tunnels and captured more than 100,000 pages of documents revealing the enemy’s operational structure and the identity of agents operating throughout South Vietnam. They seized 90 heavy weapons and tens of thousands of rounds of ammunition. They suffered eight killed and 30 wounded, while the American units had 14 killed and 76 wounded. Many of the men had been killed by booby traps.

The operational history reported enemy casualties at “128 confirmed killed, and another 190 probably killed, as well as 92 captured and another 509 suspects detained.” Many more enemy personnel probably died in the caverns and remain lost to history. American officials later asserted that the enemy’s Fourth Military Region HQ had been destroyed.

This was the first American engagement fought at divisional level and, despite significant casualties, most leaders viewed it as a success. Official accounts declared the operation a success not only because of the damage inflicted but also by the intelligence data seized. One report described it as “the first allied strategic intelligence victory of the war.” The report concluded: “On D+6 the 173rd Airborne Brigade terminated Operation ‘Crimp’ in the Ho Bo region and redeployed all units to the Brigade Base at Bien Hoa by the combination of helicopter lift and motor convoy.”

More Tunnels to Destroy

Brodbeck described the results as “excellent” and declared that the “tactical elements of the Brigade did an outstanding job during this operation,” with “ground and air mobility being used very effectively to keep the VC off balance.”

However, in retrospect, it proved a partial victory. The allies had been unable to engage the enemy in a conventional battle and were unprepared and ill-equipped to deal with the discovery of the tunnels. Strategically, while the VC suffered significant losses, the allies had only partially cleared the battle zone. Yet Operation Crimp staggered the communists, so much so that Hanoi chastised its forces “to avoid being surprised like this again.”

The tunnels continued to act as a vital enemy transit and supply base, which they used to attack Saigon during the 1968 Tet Offensive. Within the three years following Operation Crimp, additional operations sought to eradicate the Cu Chi tunnel complex, with limited success.

In 1969-1970, as part of a general air offensive, the Air Force initiated B-52 attacks that dropped delayed-fuse bombs which penetrated deep into the earth prior to exploding. This chewed giant holes in the ground where the tunnel complex had been and crippled them.

The labyrinth had taken years to destroy. Perhaps Gen. Westmoreland best explained why when he later said, “No one has ever demonstrated more ability to hide his installations than the Viet Cong; they were human moles.” During the Vietnam War, allied “tunnel rats” and “ferrets” would continue to develop effective ways to neutralize tunnels as enemy havens.