On Sunday, June 3, 1973, the sky was bright with scattered clouds over the grounds of the Paris Air Show in Val-d’Oise.

The stars of the show that year were two supersonic transport (SST) aircraft: the Anglo-French Concorde and the Soviet Tupolev Tu-144. Supersonic travel for civilians was a novel and exciting concept, and interest in the two SSTs was high. Soviet pilot Mikhail Kozlov had publicly bragged about how impressed spectators would be with the Tu-144.

“Just wait until you see us fly,” he said. “Then you’ll see something.”

He had no idea just how accurate his prediction would be.

Concorde went up first that day and had an uneventful flight. Later, the Tu-144 took to the skies and after a touch-and-go roared back into the air with its gear down and its famous “moustache” canards fully extended. Moments later, the aircraft stalled and went into a steep dive from which it never recovered.

Film of the flight shows the Soviet plane disintegrating in the air before it crashed into a group of houses. More than 250,000 people witnessed the crash, which took the lives of the eight flight crew members and six people on the ground. The cause of the crash was hotly debated, with some concluding the Tu-144 was flying beyond its safe parameters in an attempt to wow the crowd and others postulating that it was trying to avoid a Mirage jet that may have been attempting to photograph it.

Whatever the case, the disaster was emblematic of the entire Soviet SST program.

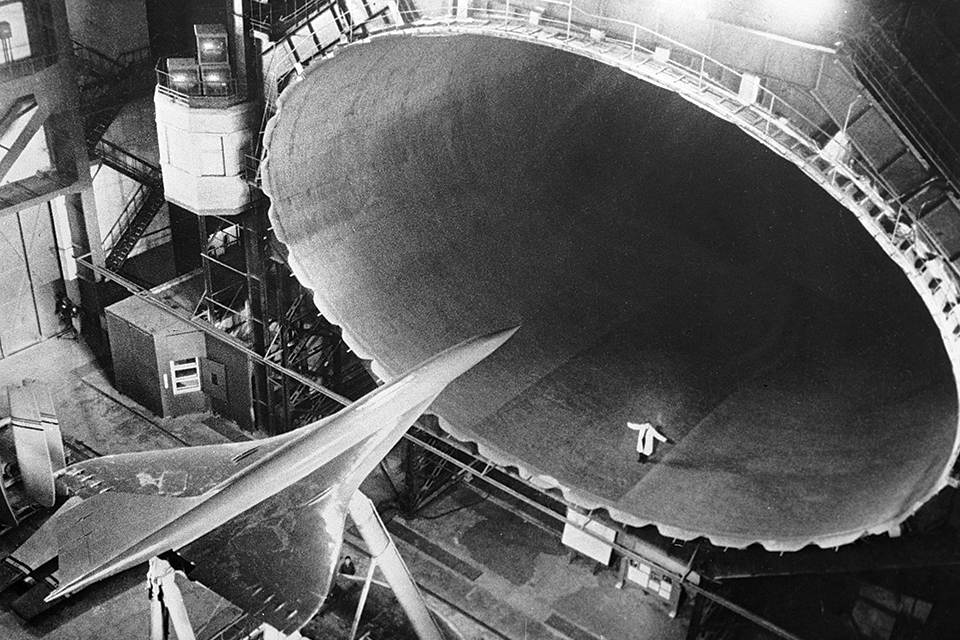

While mostly forgotten today, the Tu-144 program was the subject of intense research, development, funding and manpower in the Soviet Union. Conceived in the early 1960s, the program was intended to produce an aircraft capable of supersonic flight that could be used for both passenger and cargo transport. Just as Concorde used a Handley Page HP.115 as a delta-wing testbed, the Soviets studied thin delta wings with a modified MiG-21. With its long, narrow fuselage and double delta wing configuration, the Tu-144 bore a strong resemblance to Concorde (so much so that the press dubbed it “Concordski”). Both Concorde and the Tu-144 had a movable nosecone to increase visibility during takeoff and landing and both aircraft featured a tailless design.

The canards on the Tu-144, positioned like a pair of dog ears aft of the cockpit, were a notable difference between the two SSTs. Initially powered by four Kuznetsov NK-144 afterburning turbofan engines, the Tu-144 could cruise at Mach 2 and by some reports topped out at Mach 2.2, slightly faster than Concorde.

Although 16 Tu-144s were built, only nine were production models. The Tu-144 was both first to fly (1968) and first to fly supersonic (1969), beating Concorde on both scores, partially due to its truncated testing regimen. The Soviet SSTs were used to cover the somewhat unusual Moscow to Almaty, Kazakhstan, route. This was primarily due to the fact that the Tu-144 was incredibly noisy and the route was sparsely populated.

While the plane’s interior was posh by Soviet standards, the cabin was still quite cramped. Noise was also a major issue inside the aircraft. The Tu-144 had to use afterburners to take off and cruise at its top speeds, leading to what was described by passengers and reporters as a deafening roar inside the cabin. People seated next to each other had to shout to be heard or pass notes back and forth to save their voices.

Despite its shortcomings and the trauma of the Paris Air Show crash, the Tu-144 was a source of tremendous pride in the Soviet Union. Although rumors abounded that espionage informed its design, many of the similarities between the Tu-144 and Concorde were probably simply due to the fact that they were designed in the same era to fly similar flight profiles at essentially the same speeds.

After entering service, the Tu-144 fleet experienced its share of troubles. The planes developed a reputation for unreliability, and the Soviet government worried about bad press if another major accident were to occur, leading to limited flights and relatively few passengers. Airframe cracks, landing gear troubles, blaring alarms that could not be silenced and fuel tank failures were just some of the problems.

Disaster struck the program a second time on May 23, 1978, when a fuel line ruptured on a Tu-144D during a test flight and leaked eight tons of fuel inside the right wing. Three engines failed but the pilots managed to make an emergency landing near Yegoryevsk southeast of Moscow. Two members of the flight crew were killed and the plane caught fire after landing and was a total loss. In 1980, another Tu-144 only narrowly avoided disaster when it suffered an engine compressor disc failure that prompted an emergency landing.

Given the rushed production, cost, liability and public failures of the Tu-144, the Soviet government canceled the SST program in July 1983. Some Tu-144s were later used as airborne laboratories and to train Soviet cosmonauts. Most of the aircraft were eventually put on display, all in the Soviet Union except for one that stands next to a Concorde at the Auto & Technik Museum Sinsheim in Germany. One Tu-144 was even offered for sale on eBay with a starting bid of $7.5 million, though it failed to sell.

One happy postscript to the Soviet SST tale was the resurrection of a Tu-144D as a NASA research craft. The plane, which had only 83 hours of flight time and had last flown in 1990, was transferred to NASA in 1994 and outfitted with new engines. It functioned well as a testbed for NASA’s High Speed Research (HSR) program before it was retired in 1999 after having made just 27 flights.

Despite the Tu-144’s troubled operational history, the Soviet SST was in many ways ahead of its time. To this day, it remains a striking and impressive aircraft that will always be remembered as the first supersonic passenger plane.

This article originally appeared in the May 2020 issue of Aviation History.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.