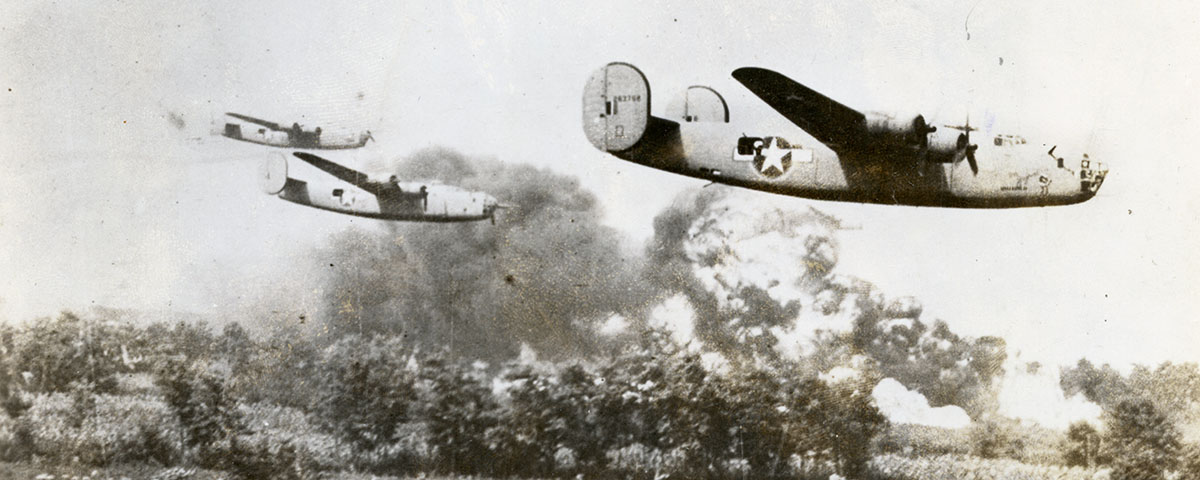

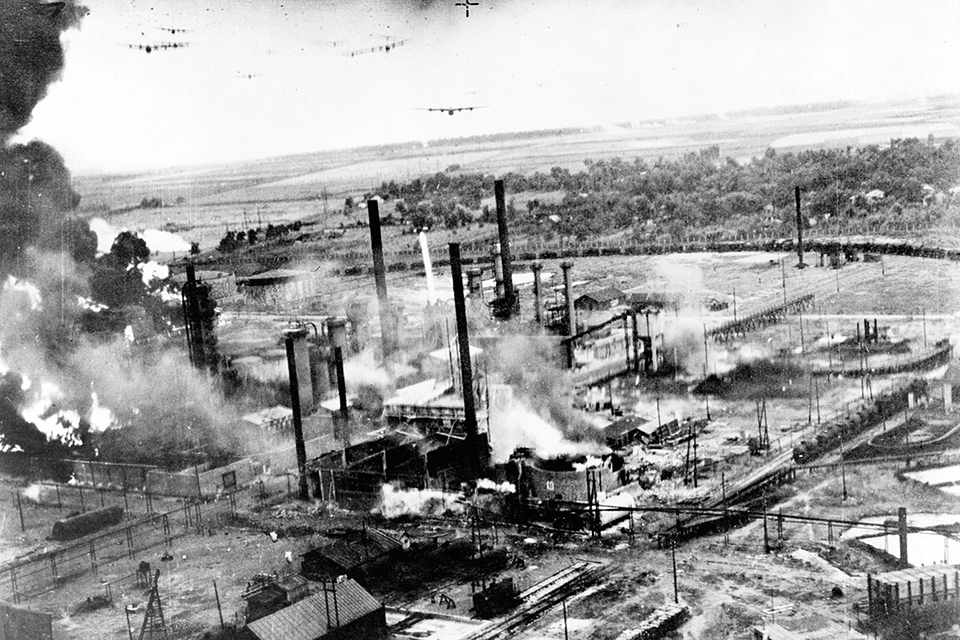

The events in the skies over the Mediterranean and southern Europe on August 1, 1943, have long been a historical bone of contention. On that fateful day 178 Consolidated B-24D Liberators of five heavy bomb groups, carrying more than 500 tons of bombs, took off from bases in Libya on one of the most audacious aerial raids in history, code-named Operation Tidal Wave. Their targets were vital oil refineries around the Romanian city of Ploesti. Seven of Europe’s largest and most modern refineries were targeted, including Astra Romana, capable of processing more than 2 million tons of oil per year. Ploesti produced all the aviation fuel used by the Luftwaffe.

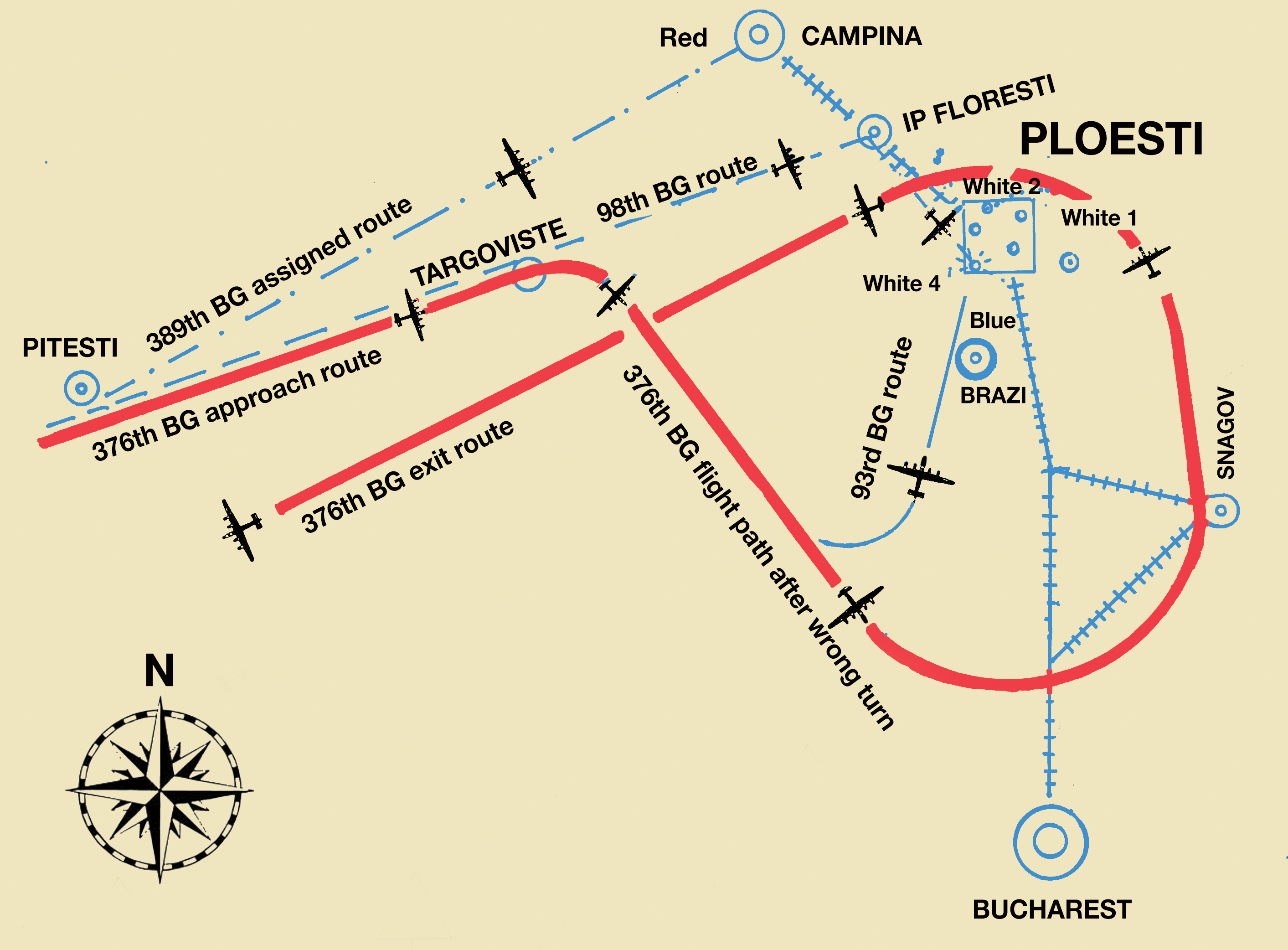

The raid was conceived by Colonel Jacob Smart, at the time considered one of the best planners in the U.S. Army Air Forces. After following a carefully laid-out course, the bombers would descend to low altitude along the southern foothills of the Transylvanian Alps to reach the third and final initial point (IP), then turn southeast toward the refineries. They would attack at low level in a five-mile-wide swath, aiming for pinpoint targets to destroy the key installations without hitting the city itself.

If all went well, the massive aerial assault would cut a third of Adolf Hitler’s oil refining capacity in less than 20 minutes.

But all did not go well, and after a disheartening series of mistakes, accidents, bad luck and determined enemy defense, Tidal Wave succeeded in destroying only two of the refineries and damaging three others—at the terrible cost of 54 Liberators. After nearly 16 hours and some of the most savage and desperate fighting ever seen in the air, 310 men were dead, more than 300 wounded and 108 taken prisoner in Romania. More were imprisoned in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, or interned in Turkey.

Recommended for you

What went wrong with operation tidal wave?

What went wrong? That question was officially answered by the USAAF two weeks after Tidal Wave, but to this day it has inspired endless debate among military historians. Among the official explanations was the loss of the lead mission navigator on a plane that unaccountably fell into the Ionian Sea. But there was much more to the story.

Participants in the raid included two bomb groups of Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton’s Ninth Air Force, the 376th “Liberandos” under Colonel Keith K. Compton and the 98th “Pyramiders” commanded by Colonel John “Killer” Kane. They were joined by three groups from the Eighth Air Force in England: Colonel Leon Johnson’s veteran 44th, the “Eight Balls”; the 93rd “Traveling Circus,” commanded by Colonel Addison Baker; and Colonel Jack Wood’s fledgling 389th “Sky Scorpions.”

Compton’s force increased altitude to 12,000 feet and maximized power, while Kane’s group remained at lower altitude and cruise power for maximum fuel economy, increasing the distance between the two main forces. A high storm front over Albania further separated the forces. Orders calling for total radio silence made it impossible to regroup.

Finally, a disastrous wrong turn short of the final IP by Compton and Baker caused the leading groups to head for Bucharest instead of Ploesti. After that the entire mission was a shambles. Compton ordered the 376th to break off the bomb run and hit targets of opportunity. The 93rd was badly mauled attempting to hit White Four, Kane’s target.

Group, squadron and element leaders, pilots and bombardiers had to improvise and do the best they could. Kane’s and Johnson’s groups, arriving almost 20 minutes later, were forced to bomb burning targets, further adding to the day’s chaos. The alerted German and Romanian defenders found the Americans’ low-flying bombers easy targets, and Liberators fell with terrifying frequency.

What do we think now?

Those are the main points of what history considers the reason for Tidal Wave’s failure. Yet history is rarely chiseled in stone. And the best source of information is often those who were there.

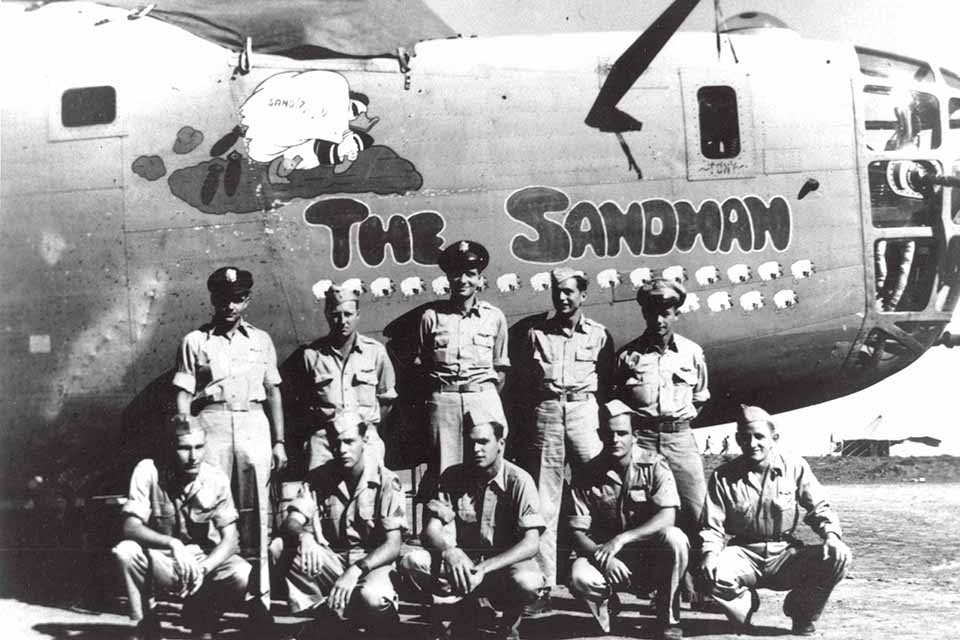

Major Robert W. Sternfels is a veteran of Kane’s 98th Bomb Group at Ploesti. On the drive to White Four, Sternfels was in the thick of it, at the controls of his Liberator, The Sandman. Perhaps the most iconic image from the raid shows The Sandman emerging from a pall of smoke and flames as it skirts refinery smokestacks at White Four.

When large aircraft fly in close formation, it creates turbulence capable of tossing 30-ton bombers around like leaves in a storm. “The prop wash was fierce,” Sternfels recalled during an interview at his Laguna Beach home.“Both my copilot Barney Jackson and I had our hands full just trying to stay on the bomb run.”

He has vivid memories of following Kane along the railroad line leading to the city. The Germans had put an ingenious flak train on the tracks paralleling the bomb run. It hosed deadly point-blank anti-aircraft fire into the low-flying B-24s. Kane led his 39 planes right into the fires and towering black smoke rising from Astra Romana, already hit by bombs from the shattered Traveling Circus.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Sternfels, a veteran with more than 300 combat hours on 50 missions, admitted he had never seen anything like it before or since. “When we went into that black smoke, I could only use instruments. Balloon cables were all around,” he said, referring to the low barrage balloons with explosive-laced cables the Germans had deployed over the refineries, “but I couldn’t see them. The right wing struck one and fortunately the propeller broke it. I was more scared at that moment than I’ve ever been in combat. I don’t know what we hit with our bombs. The target was nearly impossible to see.”

Many of the bombers ended up as long flaming smears of wreckage in the fields around the target. Somehow the pilots of The Sandman managed to bring their ship and crew back to Benghazi, one of the 26 survivors of Kane’s original force.

MOre than met the eye

According to Sternfels, there was a lot more going on behind the scenes that affected the mission’s outcome than is commonly known. The roots lay with Colonel Jacob Smart, the man most responsible for the audacious Tidal Wave plan. “Smart conceived the entire low-level concept, the route, approach and bomb run for each plane,” said Sternfels.

The four main groups were to turn onto the bomb run in waves of several planes each, keeping formation in the turn. Smart sold the idea to the USAAF brass, but the men who would actually have to carry it out didn’t think it could be done. Among those was Kane, who never minced words in expressing himself. “During the initial mission briefing meeting Kane said, ‘What idiot armchair lawyer from Washington planned this one?’” remembered Sternfels. “It looked good on paper, but that turn was totally impractical.”

Smart’s lack of understanding of how large bombers behaved in close formation was obvious to the pilots. “We practiced staying in try even once and wouldn’t work. And that’s exactly what happened. We were in formation as we reached the IP. But after that turn the entire formation was scattered and it was impossible to get it back together in the few minutes we had before we reached the target. We were supposed to be in the fourth wave, but were so tossed around, to this day I can’t tell you which wave we ended up in.”

Sternfels related one surprising incident that revealed Smart’s unsuitability for the task of planning the raid. “On July 15, just two weeks before Tidal Wave, my crew and I were preparing for a mission to Foggia, Italy, when a staff car pulled up. And out stepped Smart, fully geared up in brand-new flight suit and Mae West life preserver. He came up to me and said, ‘I’d like to fly with you today as an observer.’ Smart was on the flight deck with me, Barney and our flight engineer, Sergeant Bill Stout. He was standing there between our seats watching as we went through our checklist. I asked him if he would step back to let my flight engineer come forward and call out speed and engine readings. Smart did so and we took off.”

Passenger interference

On the way north toward Italy, Smart again came between the pilots’ seats. Then he did something virtually unheard of in any aircraft. “He reached out to adjust the fuel mixture controls,” said Sternfels, still astonished after more than 68 years. “You just don’t do that if you’re a passenger. Even a general doesn’t do that without the pilot’s permission. I didn’t say anything but adjusted the mix to what I wanted and we flew on. A little while later, Smart did it again!” That was too much of a breach of protocol for Sternfels.“I said,‘Colonel, please don’t touch the controls!’ He didn’t say anything.

“In 1993 I went to South Carolina to interview Smart,” the veteran pilot related. The meeting between the Tidal Wave planner and pilot was pleasant but brought an astonishing revelation. “I always wanted to ask him about his actions in my plane,” Sternfels recalled. “But I didn’t want to just come out with it. So I asked him in a roundabout way, ‘By the way, how many hours did you have in B-24s before that mission with me?’” Smart’s answer stunned Sternfels. The man who had conceived and planned the complicated raid admitted, “I just completed my first check-out ride the week before.” So until just three weeks prior to the huge mission he had planned nearly six months earlier, Smart was totally unfamiliar with the B-24D or how it handled in close formation. “I don’t know if he flew a combat mission prior to Foggia,” Sternfels said.

Sternfels also asked Smart, “Why didn’t we send some [de Havilland] Mosquitoes to photograph the target?” Smart said they didn’t want to alert the Germans. “So our briefings never mentioned the heavy flak or barrage balloons,” Sternfels pointed out. “We were told the flak guns were manned by Romanians who would run to the shelters when we flew over. We didn’t know how vicious the flak would really be. They knew we were coming. Maintaining radio silence was a moot point. Of course no one could know that then, so we can’t be blamed for trying to keep the Germans in the dark. However, radio silence worked against the mission as soon as things went wrong.”

Colonel catastrophe

According to Sternfels, however, a far more telling reason for Tidal Wave’s ultimate tragedy rested with another man, Colonel Keith Compton, who led the mission. “I don’t like to say anything bad of a man who is no longer alive to defend himself,” Sternfels commented cautiously, “but Compton was very confident and at times arrogant. He was accustomed to doing things his own way. That was a primary reason for the way the mission came apart.” Sternfels’ reasoning was based on his own observations before, during and after Tidal Wave and examination of documents and photos. He interviewed several other veterans of the operation, including Compton in 2000, at that time a retired lieutenant general.

Compton’s lead 376th Liberator, Teggie Ann, which also carried the mission commander, Brig. Gen. Uzal W. Ent, took off from Benghazi at 0600. Berka Two and Terria, the 376th and 93rd bases, were much closer to the coast than Lete, Kane’s field. Once the Liberandos were assembled, Compton put his plane on high power settings and headed north. In a relatively short time the 376th and the 93rd were far ahead of the 98th’s desert-weary ships, which stayed at lower power settings because Kane was concerned about wearing out their sand-scoured engines. “The gap started at takeoff and widened over the Mediterranean,” Sternfels explained. “Compton never gave a thought to the following groups.”

unlucky lead

More controversy surrounded the bomber carrying 1st Lt. Robert W. Wilson, whom some sources say was the lead mission navigator. After a series of violent pitch oscillations, the B-24 Wilson was aboard, Lieutenant Brian Flavelle’s Wongo Wongo!, flipped onto its back and fell into the Ionian Sea, killing the entire crew.

“Losing a plane and crew was bad enough,” said Sternfels. “But Flavelle wasn’t carrying the lead navigator. That implies he led the mission. If Flavelle was in the lead ship, Compton would have seen him go down.” Several other crews did see the crash.

“Compton told me he didn’t learn about Flavelle’s crash until he returned to Benghazi,” Sternfels pointed out. “Compton admitted he led the mission from takeoff to landing. I found documentation to back it up.”

Another B-24 piloted by Lieutenant Guy Iovine dropped out of the formation to assist Flavelle. “They later said they wanted to drop life rafts,” he explained. “They weren’t able to climb to rejoin the mission and had to turn back. But there’s no way to drop life rafts from a B-24D. They’re in compartments on the top of the fuselage. You can’t get at them in flight.” Some sources say Iovine’s plane was carrying the deputy mission navigator.

By the time the leading groups reached the mountains of Albania, Compton and Kane were separated by at least 30 miles. Ploesti, a controversial book by James Dugan and Carroll Stewart, claimed that storm clouds over the Albanian mountains convinced Kane to begin circling for what was known as “frontal penetration,” a maneuver to prevent collisions in clouds. This earned a strong comment from Sternfels: “We never did that. That was a fictional explanation for the wide gap between the two formations. But it never happened. In fact I’d never heard of it until long after the war. Our navigation logs show we climbed and worked our way through.” The book also stated that at Compton’s altitude, there was a strong tailwind that was not present at Kane’s altitude, further adding to the gap. This was untrue, according to Compton.

As for the confusion supposedly resulting from the loss of the two most trained navigators, Sternfels said, “That’s baloney. If only two men knew the route, why did we take along 176 others? All the navigators were trained and had very cleverly drawn low-level course charts.”

Navigational errors

How, then, could so many qualified navigators have failed to keep the force on course at the critical moment?

“I found a photo of Compton just prior to takeoff. In this photo, he is holding under his arm a set of charts and maps. Compton was familiar with the route and approach. But his job as the mission leader wasn’t to be looking at maps. That was Wicklund’s job,” Sternfels said, referring to Captain Harold Wicklund, one of the most experienced navigators in the USAAF. Wicklund had already flown to Ploesti on the “Halverson Project” raid of June 12, 1942.

According to Compton’s copilot, Captain Ralph Thompson, Compton had the charts and maps on his lap during the approach to the IP. “The 376th and 93rd reached the first IP at Pitesti and continued on,” said Sternfels. Kane and Johnson were by now almost 60 miles behind the lead force. “When they reached Targoviste, the second IP, Compton turned the force southeast,” he continued. “Most of the other pilots realized it wasn’t the right place.” Several Liberando pilots broke radio silence to let Compton know he had turned too early, but he didn’t have his radio turned on. If he had heard the calls, he might have saved the mission, as it would have taken only a few minutes to get back to the correct course. Instead, Compton continued on and didn’t realize his mistake until he saw the church spires of Bucharest ahead. At that point he asked Ent for permission to tell the group to break off and bomb targets of opportunity; Ent agreed.

Questionable orders

The Circus’ 32 remaining ships (five had turned back), led by Baker and Major John Jerstad in Hell’s Wench, turned east to try an improvised attack on Kane’s target, White Four. They flew into a deadly hailstorm of flak. German and Romanian gunners found ripe targets at point-blank range, and 88mm, 37mm and 20mm batteries took a terrible toll on the low-flying B-24s. When the Circus emerged from the smoke and carnage, Hell’s Wench wasn’t among them. Only 15 of the attacking 93rd Group Liberators returned to Benghazi.

“It still amazes me that Compton ordered the 376th to break off the bomb run and hit targets of opportunity,” said Sternfels. “Many planes just jettisoned their bombs rather than face the flak. They weren’t even under fire when he sent that order.”

Interviewed by Sternfels, bombardier 1st Lt. Lynn Hester said: “I wasn’t told to drop the bombs. Compton pulled the lanyard on the pilot’s pedestal and dropped them right through the doors, pulling them off their tracks. I never saw the target nor did I see the bombs explode.” Since a firing unit switch must be turned on for the ordnance to be fully armed, Compton’s bombs probably never exploded.

Then Compton compounded his error. After conferring with General Ent, he sent “MS” (mission successful) to Benghazi. The MS signal went out while the 93rd was being totally mauled.

“Very few of the 376th bombed a refinery,” said Sternfels. “Otherwise they’d have lost a lot more planes flying into that flak.” Only three of the 28 Liberandos B-24s managed to do any real good with their bombs. “Those were led by Major Norman Appold, a very smart and excellent pilot,” he said. Appold took his element around the city and hit White Two, a Circus target.

Kane’s, Johnson’s and Wood’s groups made the correct turn. But by then Tidal Wave had become a total debacle. The flak train, flak batteries and fighters were fully alerted.

After Compton returned to Benghazi, he went into conference with Brereton and Ent. A photo Sternfels found after the war tells a very compelling story. “It was taken only minutes after Compton’s plane landed,” he explained. “If you look at his face, he doesn’t look like a man who led a successful mission, nor does he look like someone who ran into a ton of bad luck. He looks guilty.”

Tidal Wave’s final outcome was both a failure and a success. While only two refineries were totally destroyed and three others moderately damaged, the raid eliminated vital oil refining capacity just when Hitler’s war machine needed it most to stop the relentless Soviet drive toward the Fatherland.

In the wake of the costly mission, the USAAF awarded five Medals of Honor to pilots, both living and dead. Kane was honored for leading his group into the fires and smoke of White Four. Johnson, whose 44th successfully struck White Five, also received the medal. Three medals were awarded posthumously: to Baker and Jerstad of Hell’s Wench, and to the 389th’s Lieutenant Lloyd D. Hughes, who dropped his bombs on target despite flames erupting from his B-24. Every man who participated in Tidal Wave was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

There were countless other stories of heroism in the deadly skies over Ploesti, some of which were recorded and others that will forever remain unknown. But to many who look back on the dangerous mission today, every single young man who climbed into a Liberator on that Sunday morning was a hero. That was certainly how Kane felt. A warrior with the soul of a poet, he wrote a deeply moving epitaph:

‘To the Fallen of Ploesti’

To you who fly on forever I send that part of me which cannot be separated, and is bound to you for all time. I send to you those of our dreams that never quite came true, the joyous laughter of our boyhood, the marvelous mysteries of our adolescence, the glorious strengths and tragic illusions of our young manhood, all of these that were and perhaps would have been, I leave in your care, out there in the blue.

Mark Carlson writes frequently on aviation topics from San Diego, Calif. Major Robert W. Sternfels (USAF, ret.) is the author (with Frank Way) of Burning Hitler’s Black Gold, which is recommended for further reading. Also see The Ploesti Raid Through the Lens, by Roger A. Freeman.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.