Making artwork has been a passion of mine since childhood. So has the study of the Civil War, in particular the history of the 154th New York Infantry. My interest had been stirred by family stories and relics of my great-grandfather John Langhans, who enlisted in September 1864 and served in the 154th during Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s marches through Georgia and the Carolinas. Since my elementary school days in suburban Buffalo, N.Y., I had been searching for information about my ancestor’s regiment. The Civil War centennial of 1961-65, which coincided with my high school years, proved to be a good time to develop my interest. By the time of a 1970 visit to Coster Avenue, I had set a goal to write and publish a regimental history of the 154th before my 50th birthday.

That 1970 visit was made memorable because of a critical occurrence. The roofing company whose property abutted the southern edge of Coster Avenue was erecting an addition to its warehouse. A blank concrete block wall, 80 feet long, was going up about 10 feet behind the 154th’s monument, which the regiment’s veterans had erected in 1890. I was dismayed. A concrete block wall would form an unsightly backdrop to the monument of a regiment that had come to mean so much to me.

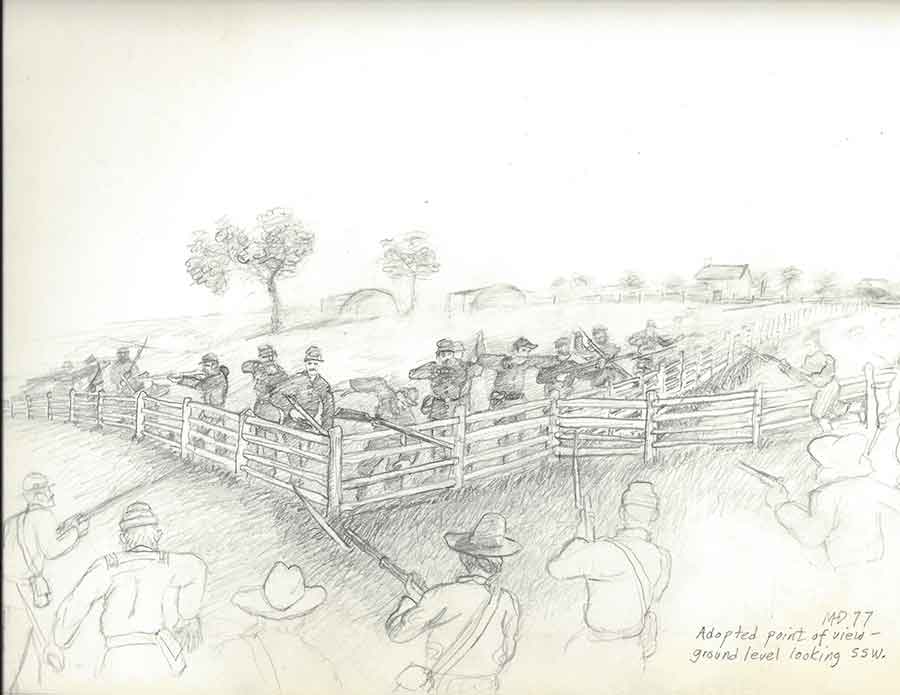

Sometime later, an idea came to me—I could make that wall “disappear” by covering it with a mural depicting the Brickyard Fight, on the very site where the clash took place. In my mind, however, the mural wouldn’t simply commemorate a single regiment—the 154th—but rather all of the Union and Confederate soldiers that had been involved.

In 1977, I went public with my proposal and received advice and encouragement from several key individuals, including Gettysburg National Military Park historian Kathleen R. Georg, renowned author William A. Frassanito, and the roofing company’s proprietor Roy E. Coldsmith Jr.

What I had taken on was, of course, a daunting project. It was my introduction to Rhode Island–based muralist Johan Bjurman that proved a vital turning point. Rather than paint the mural directly on the concrete wall, with its rough, textured surface broken by a gridwork of mortar, Johan recommended that we paint it like an oversized billboard on detachable panels, and then affix it to the wall.

Working in Johan’s studio over five weeks, we finished the mural. Johan did the portraits and figures; I the landscape, fences, muskets, and accoutrements. Portraits of several known casualties of the 154th New York were included, among them Sergeant Amos Humiston. I also decided to include a self-portrait as a soldier, as Paul Philippoteaux had done in his landmark Gettysburg Cyclorama.

We dedicated the mural on July 1, 1988, the battle’s 125th anniversary, and would receive appreciation from several descendants of soldiers who had fought there. Although Coster Avenue soon settled back into its usual lonely quiet, the GNMP and roofing company itself were more diligent in maintenance of the site with the increase in visitors. Placement of a sheet metal frame around the mural’s perimeter by Coldsmith also helped keep animals from nesting around it.

The mural held up beautifully for seven years after its installation. But during the next year the varnish started to blister. As the turn of the century approached, nature’s ravages continued. The painting needed an overhaul. I made a halfhearted attempt to solicit funds for the restoration project. In 2001, my fortune changed in dramatic fashion, thanks to the legendary Edwin C. Bearss, chief historian emeritus of the National Park Service and a celebrated guide to American historic sites. In May, I learned that a group known as the Bearss Brigade raised money every year to donate to a Civil War historic preservation cause of Ed’s choice. This year he had chosen the Coster Avenue mural.

With desperately needed funding in hand, Johan and I wasted no time. Over 13 days that September and October—fortunately in splendid weather—Johan and I succeeded in repainting and refinishing every square inch of the mural. In 2006, Johan spent a couple of days washing the surface and giving it another coat of varnish. Our hope was to prolong its life with periodic maintenance. Up to 2010 or thereabouts the painting was still looking good, but then the inevitable deterioration set in, this time accompanied by some structural damage.

To my regret, the battle’s sesquicentennial passed in July 2013 with the mural still in shabby shape. Realizing we faced another total repainting, as well as fixing various structural problems, Johan and I began to consider an alternative mode of presenting the mural, one that would stand up to the elements and last. We eventually decided on reproducing the mural on glass. An Israeli firm, Dip-Tech, had developed an innovative method of printing on glass using ceramic inks in a giant inkjet printer. After the ink is applied, the glass is fed through two kilns, and the heat fuses the ink to the glass, permanently and impenetrably. When done, the back of the glass containing the imagery is just as smooth to the touch as the unadorned front.

It took some time to go that route, and we were fortunate to work with several reputable companies with expertise in this remarkable technology. We were able to make some important changes in reproducing the mural, most important emphasizing the sweep of Hays’ Brigade through the wheat field and around the Union left flank. Johan rendered the Confederates as more ragged than in the two previous versions, and he added an animated portrait of me.

Installing the new mural did not proceed in clockwork fashion, but we finally succeeded in finishing placement of the entire transformed mural on the wall in December 2015.

My goal in creating the Coster Avenue mural was to draw attention to an overlooked part of the Battle of Gettysburg and a neglected portion of the battlefield, and to commemorate the New Yorkers, Pennsylvanians, North Carolinians, and Louisianans who clashed at John Kuhn’s brickyard. How well I’ve succeeded others will judge.

I find this to be telling, however: During my visits to Coster Avenue before the mural was installed, I never saw another person there. I can say with satisfaction that after the mural went up, every time I’ve been in Gettysburg I’ve encountered visitors at Coster Avenue. For 30 years, our mural has stood in the famed Brickyard. My hope is it will stand for another 30—and more.

Adapted with permission from Gettysburg’s Coster Avenue: The Brickyard Fight and the Mural, by Mark H. Dunkelman (Gettysburg Publishing, 2018).