The three Russians were acquaintances. Two were recent immigrants, while the third had been in North America for a time. Hard labor in the copper mines of Butte, Mont., had not fulfilled their idea of the “American Dream.” There had to be an easier way to make a living. They considered train robbery. As it was less common north of the border, they resolved to rob a Canadian train.

On Monday, Aug. 2, 1920, a warm summer’s day in southern Alberta, Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) passenger train No. 63 chugged west. Soon entering the Rocky Mountains, it passed in turn through the neighboring towns of Bellevue, Frank, Blairmore and Coleman. Back in the baggage car Bill Staples readied freight to be unloaded at Sentinel, the next stop, at a passenger’s request.

Conductor Sam Jones checked the time on the prized gold pocket watch he’d recently purchased in Lethbridge. On returning it to his breast pocket, he found himself staring down the barrel of a semiautomatic pistol. As the gunman ushered Jones back to the baggage car to join Staples, the conductor was able to surreptitiously tug the emergency cord once. Three pulls would have called for an immediate stop, putting everyone in danger. Once signaled the train crew to stop at the next convenient place, which was Sentinel.

Meanwhile, two other robbers were relieving male passengers of their valuables, while leaving female passengers alone. On finishing their collection, the pair joined the third robber in the baggage car. As the train slowed for the stop at Sentinel, they jumped off and ran into the brush south of the tracks. The inept trio, who had ignored the safe containing several hundred dollars, made off with little more than $400 and Jones’ gold pocket watch.

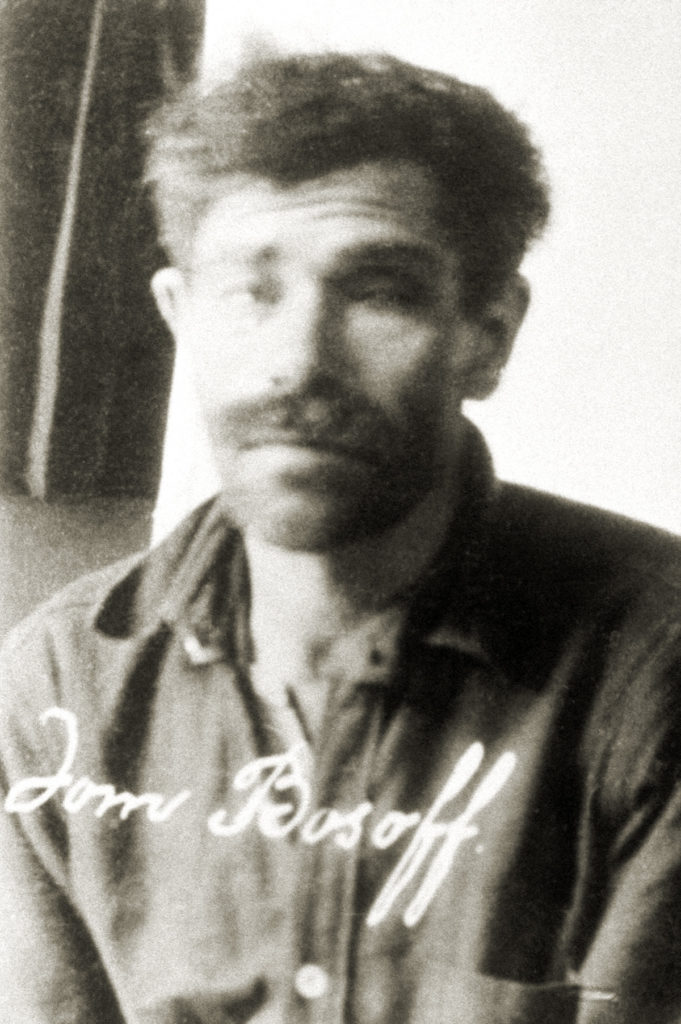

Authorities soon telegraphed descriptions of the suspects to Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Alberta Provincial Police (APP) stations in the area. Also joining the hunt were CPR detectives—two of them, William R. MacLeod and Albert Robine, having suffered the ignominy of being robbed. Jones informed lawmen the trio had boarded the train in Lethbridge, and police there soon identified the suspects as Tom Bassoff, George Arkoff and Ausbey Auloff, Russians from south of the border with prior arrests on minor charges.

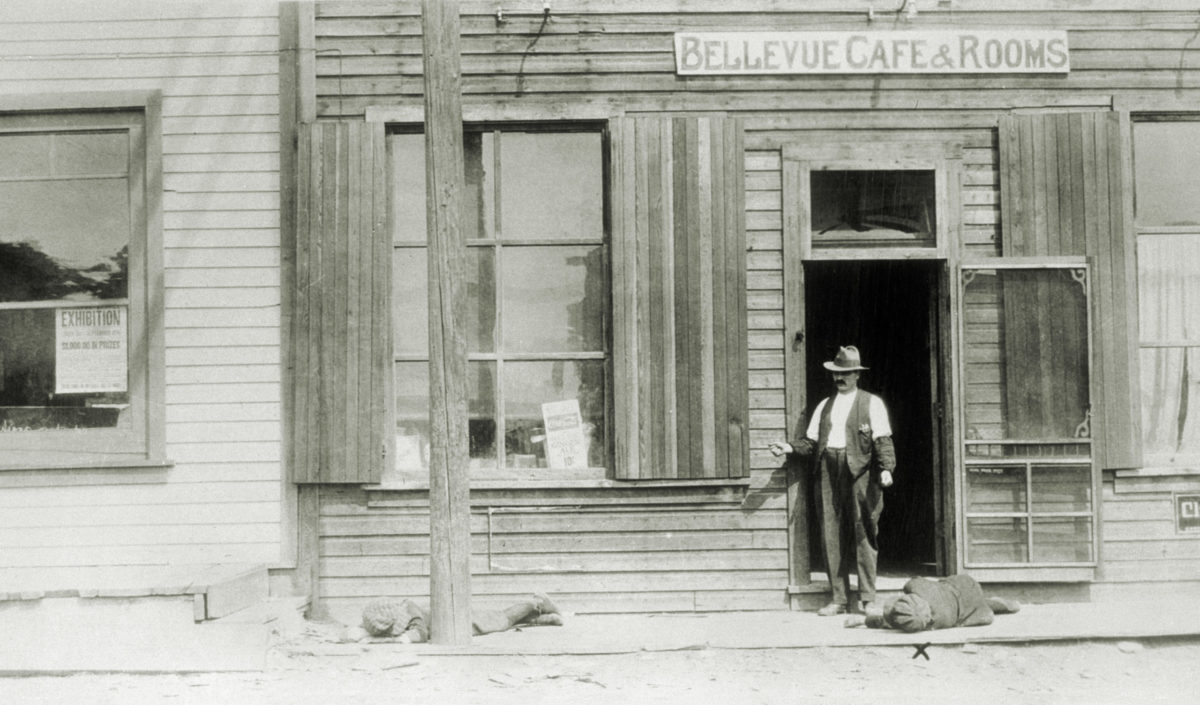

Authorities blocked all roads, stopped and searched every train, and investigated numerous sightings. The following Saturday, August 7, APP Constable James Frewin got a tip that two men answering the descriptions of the fugitives had entered a café in Bellevue. Frewin investigated with fellow Constable F.W.E. “Fred” Bailey and RCMP Corporal Ernest Usher.

Bailey stood by the rear door of the restaurant while Frewin and Usher strode through the front door. The only diners were Bassoff and Arkoff, who shared a booth. Drawing their sidearms, Frewin and Usher cautiously approached. When Frewin saw Arkoff reach for his coat, which hung beside the booth with the butt of a gun sticking out, the constable opened fire, emptying his gun and then backing away to reload. Usher, who had his gun trained on Bassoff, did not fire. Responding to the shots, Bailey rushed in and over to the booth. Frewin, in a “shell-shocked” state at having shot a man for the first time, left the restaurant. It was then, police later determined, Bassoff saw an opportunity, yanked his Mauser pistol and opened fire.

Witnesses outside the restaurant said that after hearing several shots, they watched Corporal Usher back out the front door and turn to descend the step when he caught a bullet in the back. Constable Bailey followed, immediately stumbling over Usher, who lay crumpled on the ground with his head in the doorway. Next came Arkoff, who staggered up the street and collapsed, dead from his wounds. Finally, Bassoff emerged. As Bailey tried to rise, Bassoff fired once into the top of his skull. At that Usher stirred, and Bassoff emptied his gun into the wounded constable before taking off west on foot. Searchers later lost his trail.

By nightfall the manhunt had drawn more than 200 possemen, including police from as far away as Calgary. Anyone with a gun was sworn in and told to shoot on sight. This proved disastrous. On Sunday evening, August 8, Special Constable Nick Kyslik and APP Constable J. Hidson were searching a cabin near the railroad tracks when a slow-moving freight train rumbled past. Kyslik must have seen something suspicious on the train, as he leapt from a window and chased after it. In the twilight all Hidson saw was a running figure. Figuring they had flushed the suspect from the cabin, he yelled “Stop!” Kyslik, unable to hear over the train noise, kept running, so Hidson fired, killing his partner.

Not until Wednesday evening, August 11, did CPR detectives, responding to reports of a suspect limping along the tracks near Pincher Station, capture Bassoff. Despite the bullet wound to his leg, the fugitive had limped 25 miles east over four days and somehow managed to elude 200 possemen. The following Tuesday, August 17, he was arraigned in Fort Macleod before Magistrate Harold P. Burrell on charges of holding up a CPR train and murdering two police officers. The charges were held over, as that afternoon there was a massive double funeral for the slain lawmen. A local man, Bailey left a wife and two young children. Corporal Usher was a native of Ireland with no known relatives in Canada.

On October 13th, with Justice Maitland McCarthy presiding, Crown prosecutor E.J. MacDonald was ready to proceed when someone noticed there was no council for the defense. The judge duly appointed local attorney Donald J. Matheson and gave him an hour to confer with his client. Ballistic evidence revealed Usher had four bullet wounds in his right arm and one in his body from the Luger found on Arkoff, but the corporal had nine other wounds in his body, any one of which could have been fatal, from a Mauser. Bailey had one wound from a bullet that entered his skull through his peaked cap, also from a Mauser. When Bassoff was arrested, he had on his person an empty 10-shot Mauser. That evidence alone sealed his fate. It took the jury less than an hour to bring in a guilty verdict. The judge condemned Bassoff to hang on December 22.

According to Bassoff, after the heist the trio had argued about the best escape route, and Auloff had headed west, taking Jones’ watch as his share of the loot. APP Sergeant John D. Nicholson reasoned Auloff had probably crossed the border to find work in the Western States, where Russians dominated the lumbering business. With the help of local police Nicholson visited lumber camps and dives across Oregon and Washington, but he had no luck. A break finally came in January 1924 when Portland city police wired then Assistant Superintendent Nicholson with news Jones’ stolen watch had been pawned, and they had identified a suspect. Nicholson sent detective Ernest P. Schoeppe to Portland, only to discover the suspect was not Auloff. Under questioning, the man admitted having bought the watch from an acquaintance in Butte, Mont. On a promise authorities would drop the charge against him, he took Schoeppe to the Butte home of that acquaintance. The man who answered the door was Auloff, who had returned to his old job. Schoeppe arrested the fugitive and turned him over to Butte police.

Waiving extradition, Auloff was returned to Alberta and convicted at trial of armed robbery, for which he received a seven-year sentence. On April 5, 1926, three years into his sentence, Auloff died in prison of respiratory disease brought on by his years underground. Thus what had started six years earlier as an amateurish attempt at a holdup ended up costing three lawmen and, ultimately, three bandits their lives.