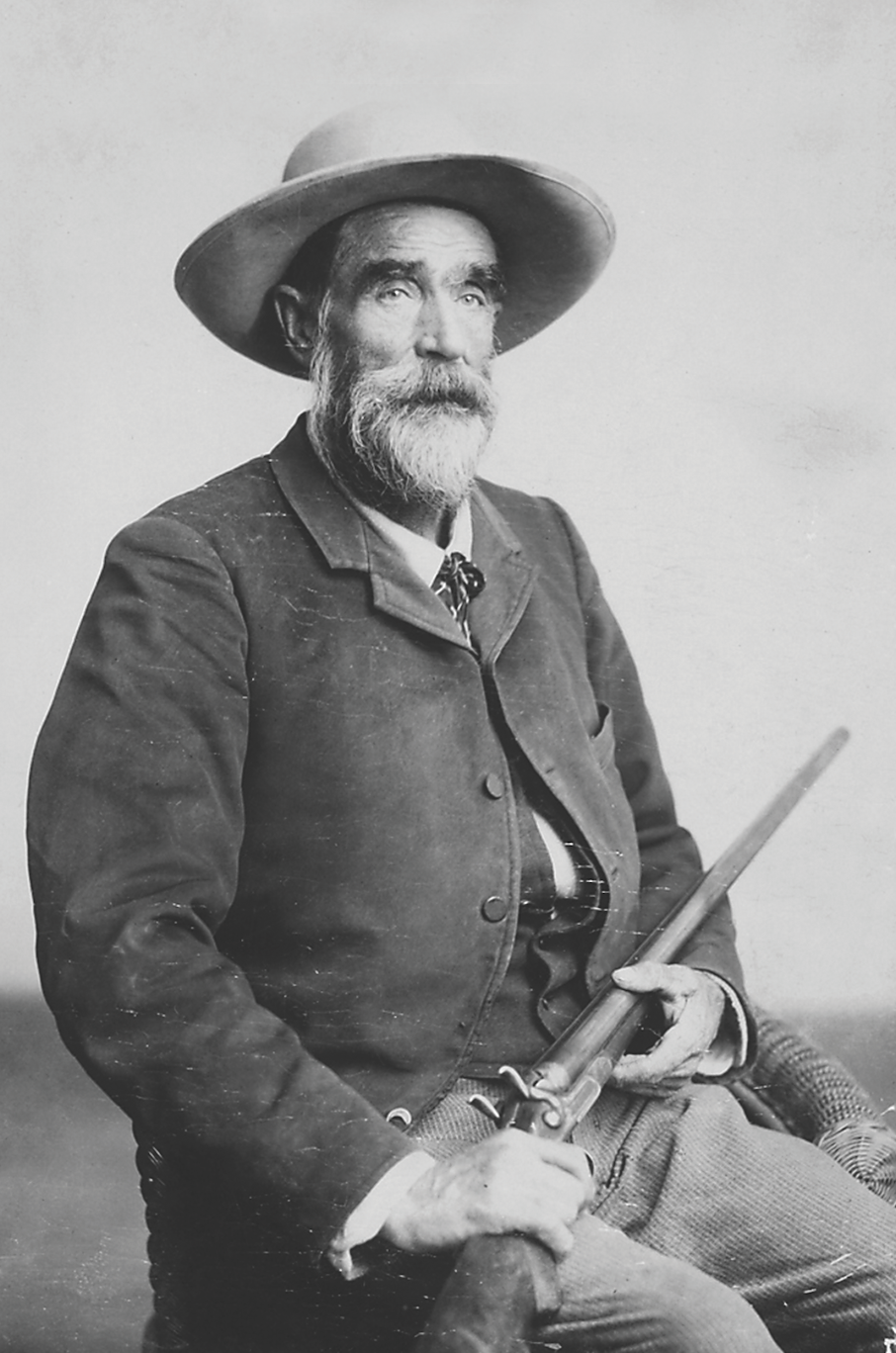

Thomas Jonathan Jeffords was an enigmatic man. Born on the westernmost tip of New York state on New Year’s Day 1832, he first ventured west of the Mississippi in 1858.

That much is known. But other details of his remarkable life, in particular his seminal friendship with the Chiricahua Apache Chief Cochise, have become challenging for the historian to flesh out or to reconstruct. He was not the type of man to call attention to himself and the indispensable role he played in brokering peace talks between Cochise and the one-armed “Christian General” Oliver Otis Howard, thus ending more than a decade of warfare between the Chiricahuas and Americans.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

As part of the terms of the 1872 treaty the general named Jeffords agent of the new Chiricahua Apache Indian Reservation in Arizona Territory. The peace lasted almost four years, until a pair of intoxicated Apaches killed two American ranchers who had illegally sold them whiskey on the reservation. That incident gave the U.S. government the excuse to close the Chiricahua reservation, discharge Jeffords as agent and move the late Cochise’s band to the inhospitable San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation.

That series of events in turn set the stage for another decade of hostilities between the Apaches and Americans—until the end of the 1885–86 Geronimo campaign and subsequent removal of nearly every Chiricahua from Arizona Territory to Florida.

RETICENT FRONTIERSMAN

Tom Jeffords was neither a braggart nor an ostentatious man—on the contrary, he was a reticent frontiersman who spoke little of himself and preferred to be left alone. “Jeffords offered little help to those who wanted to know more about him,” concluded historian C.L. Sonnichsen, who wrote extensively about Jeffords in the 1980s. “He talked with his pioneer friends about the early days, but he made little attempt to get his extraordinary story on record and made no effort at all to correct the misstatements and mistakes that got into circulation.”

One persistent “fact” that falls apart under scrutiny is that Jeffords and Cochise formed a pact in 1867 to leave mail riders alone. A review of Apache ambushes on mail riders in Chiricahua country between November 1867 and March 1869—the months Jeffords served as superintendent of the Southern Overland Maiand Express Co. line between Mesilla, New Mexico Territory, and Tucson—reveals that Apaches killed four mail riders and three soldier escorts.

After March 1869, the probable date Jeffords severed his employment with the Southern Overland, Apaches killed three mail riders, four soldier escorts and one citizen. Apache assaults on mail riders continued until October 1872, when Cochise made his treaty with Howard.

“There is a man by the name of Jeffries [sic] living at Cañada Alamosa that is well acquainted with Cochise, having been a trader with the Apaches for some length of time,” Apache Agent Orlando F. Piper wrote Colonel Nathaniel Pope, New Mexico’s Superintendent of Indian Affairs, on Feb. 7, 1871. “He informs me that he believed that he can induce Cochise and his band to come in and settle on a reservation and is willing to make the effort, provided he can have assurance from the Indian Department that he will be liberally compensated for his time and trouble in case of success.”

JEFFORDS MEETS WITH COCHISE

The timing of the letter suggests Jeffords first met Cochise in the fall of 1870. Jeffords made several statements regarding the scope and tenor of that first encounter. According to one contemporary, the trader claimed to have met with Cochise in southeastern Arizona Territory’s Graham Mountains. That source probably erred. They likely met near the Apache agency at Cañada Alamosa, New Mexico Territory, either in the San Mateo Mountains or the Black Range.

Jeffords told historian Edwin Farish he was “alone, fully armed” as he rode into Cochise’s camp. “After meeting him, I told him that I was there to talk with him personally,” Jeffords recalled, “and that I wished to leave my arms in his possession or in the possession of one of his wives whom he had with him, to be returned to me when I was ready to leave, which would probably be a couple of days. Cochise seemed to be surprised but finally consented to my proposition.”

Jeffords stayed on for a few days, getting to know Cochise, who respected the trader’s courage and sincerity and opened up to Jeffords. According to Southwestern cowhand Felix McKittrick, who worked for pioneer cattleman John Chisum and delivered beef to the agency at Cañada Alamosa, it was probably during that first conversation between Cochise and Jeffords the chief laid down ground rules for their friendship: “Don’t tell me any lies. What I tell my men is another thing, but I must always have the truth myself.”

McKittrick said Jeffords always remembered that “hint,” which remained an inviolable aspect of their relationship.

CEMENTING FRIENDSHIPS

Jeffords also met with Chiricahua Chiefs Victorio, Loco and Nana while serving as a trader at Cañada Alamosa. He enhanced his friendship with Victorio by agreeing to retrieve several horses from Navajos who had stolen them from the Apache leader in the summer of 1871. Jeffords set out in early November with three Apaches, one of whom was likely Chie, a nephew of Cochise who later helped arrange the meeting between the chief and General Howard.

Superintendent Pope and Agent Piper agreed to pay Jeffords a daily rate of $4 or $5 per day. Jeffords also issued rations to his three Apache scouts, and Piper agreed to re-

imburse the frontiersman for any expenses Jeffords incurred on behalf of the Navajos. Jeffords recovered every one of Victorio’s stolen horses except for one that had died.

THE CHRISTIAN GENERAL

Brig. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard was a humanitarian and a deeply religious man. Born in Leeds, Maine, in 1830, he entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point after graduation from Bowdoin College in 1850. He finished fourth in a class of 46 and, after a brief stint as an ordnance officer in the last of the Seminole wars, taught mathematics at West Point until the outbreak of the Civil War.

In June 1861 he was appointed colonel of the 3rd Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment and soon earned promotion to brigadier general. He saw action in several major battles, losing his right arm in the Battle of Fair Oaks on May 31, 1862. Early in his military career he became an evangelical Christian and was known as the “Christian General,” a distinction that undoubtedly helped him secure postwar appointment as commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau, a federal agency charged with aiding the roughly 4 million freed slaves.

The government could not have chosen a better man for the daunting task, for Howard brought honesty, compassion and humane conviction to the job. That said, his idealistic views, misplaced faith in humanity and lack of administrative ability triggered a round of rampant corruption.

In February 1872 Secretary of the Interior Columbus Delano, conceding that humanitarian Vincent Colyer’s recent peace mission to the Southwest had failed to achieve its goal of settling the region’s Indians on reservations, decided to send the scrupulously honest Howard to “take such action as in your judgment may be deemed best for the purpose of preserving peace with the Indians in those territories.” Delano’s selection of the Christian General was acceptable to religious and humanitarian groups as well as the military, and he would outrank every officer in the Southwest.

“All these surrounding tribes were to be quieted by my expedition,” Howard later recalled, “but the main thing was to make peace with the warlike Chiricahuas under Cochise.”

Col. George Crook, commander of the Arizona Department, was displeased at the arrival of yet another peace commissioner, which would again force him to delay military action. The fact Howard outranked him seemed to chafe Crook (who had risen to brevet major general during the war) all the more. Howard reached Arizona Territory in April and on the 15th met with Crook, whom he thought “a very fine officer, ready to work heartily with me.”

Five days later Crook wrote to Col. Gordon Granger, commander of the District of New Mexico, asking him to send Cochise under escort to Camp Apache (designated Fort Apache in 1879), where the chief could meet Howard. But Cochise had already left Cañada Alamosa rather than move to the new reservation at Tularosa, so Granger could not arrange the meeting.

In late May the general himself traveled to Camp Apache and made several fruitless attempts to communicate with Cochise. Howard did succeed in appeasing the Western Apaches before returning to Washington, D.C., in June with a delegation of Arizona Indians. After a short stay, countless interviews, speeches and a meeting with President Ulysses S. Grant, the delegation left Washington on July 10. Howard’s aide on the return trip west was 1st Lt. Joseph Alton Sladen, who had served under the general during the Civil War and in the Freedman’s Bureau.

Howard stopped in Santa Fe in late July and met with Pope, who told him a man named Tom Jeffords had once delivered a message to Cochise, and “[Pope] was confident that the man had dealt honestly with him.” Howard’s next stop was Camp Apache, where he made plans to communicate with Cochise, who was believed to be in southern Arizona Territory. At Camp Apache he and Sladen also learned Jeffords had visited with Cochise frequently and could presumably get a message to him.

MISSION TO FIND JEFFORDS

On Aug. 30 Howard led his party from Camp Apache bound for Fort Tularosa, where he believed they’d find Jeffords. The second day out they met a man named Milligan, who confirmed the wisdom of enlisting Jeffords’ services. On Sept. 4, as Howard’s party neared Tularosa, post interpreter Fred Hughes rode up. Hughes told the general Cochise “was ready to make peace.” He, too, advised Howard to contact Jeffords and take him on the mission.

Three days later Jeffords rode in to Fort Tularosa. He had been serving as a scout for troops assigned to round up Apaches who had fled from Cañada Alamosa rather than relocate to Tularosa. Howard tracked him down in the sutler’s store and introduced himself. He then asked Jeffords to track down Cochise and bring him in for an interview. After some deliberation, Jeffords responded:

“General Howard, Cochise won’t come. The man that wants to talk to Cochise must go where he is.”

“Will you go to him,” Howard then asked, “with a message from me?”

“I’ll tell you what I’ll do,” Jeffords said with a smile. “I will take you to Cochise.”

Howard quickly replied, “I will go with you, Mr. Jeffords.”

For the next week Howard, Piper and Pope met with the Bedonkohes and Chihennes, whose main wish was to return to Cañada Alamosa. Jeffords was able to convince Chie, a nephew of Cochise, to help broker a meeting between the chief and the general.

On Sept. 13, 1872, Howard, mounted on an Army mule, led the small party out of Fort Tularosa. On the 16th they reached Cañada Alamosa. After inspecting the reservation, Howard acquiesced to the Apaches’ wishes, agreeing to scrap the ill-advised reservation at Tularosa and return the Apaches to Cañada Alamosa—under the assumption all of the Chiricahuas, including Cochise, would settle there. There was no indication the chief might have other ideas.

That day Howard made two other important decisions. The first was to remove Orlando Piper as agent for the Bedonkohes and Chihennes. It was clear to the general Piper’s wards were dissatisfied with the agent. Consequently, he issued Piper a 30-day leave of absence with permission to apply for an additional 30 days. And then, evidently with Pope’s blessing, Howard appointed Jeffords agent of the proposed Apache reservation at Cañada Alamosa.

The account contrasts with a version related by Jeffords in which Cochise insisted on him as agent, and Howard had to talk the frontiersman into accepting the assignment. In fact, Jeffords had willingly accepted the position even before Cochise had agreed to the historic pact, although Jeffords’ appointment undoubtedly sealed the deal. Howard also laid out the boundaries of the new reservation.

While at Cañada Alamosa, Howard sent the supply wagon driven by Albert Bloomfield to Fort McRae, where he would replenish supplies before heading to Fort Bowie with an escort of six soldiers. On Jeffords’ recommendation Howard brought aboard as packer Zebina Streeter, who went by the moniker “White Apache.” On Sept. 18 they departed Cañada Alamosa in search of Chie’s brother-in-law Ponce, whom Jeffords insisted could guide them to Cochise and serve as interpreter.

“Ponce is a favorite friend of the old man,” he told Howard. “He and Chie will make us welcome to Cochise’s stronghold.” They found Ponce’s camp on Cuchillo Negro Creek, and with cajoling he agreed to join the party, which then set out toward the Chiricahua Mountains, where they believed Cochise to be camped.

WORKING WITH APACHE SCOUTS

On Sept. 19 Jeffords and his two Apache scouts led the party east, and 11 days later Howard, Sladen, Jeffords and scouts Chie and Ponce caught up to Cochise’s band in the western foothills of the Dragoon Mountains. The next morning, October 1, Cochise rode into their camp. After consulting with Jeffords, Chie and Ponce, Cochise asked Howard the purpose of his visit.

Howard explained President Grant had sent him “to make peace between you and the white people.” Cochise promptly assured Howard, “Nobody wants peace more than I do.” Howard jumped on that response by offering to consolidate the allied Chokonens, Chihennes and Bedonkohes on the proposed reservation in Cañada Alamosa.

To everyone’s surprise Cochise initially demurred, declaring that while he liked the country and would go himself, such a move would divide his band. He then made an unexpected request of Howard and Sladen: “Why not give me Apache Pass? Give me that, and I will protect all the roads. I will see that nobody’s property is taken by Indians.” Cochise convinced Howard to wait 10 days while the chief gathered his captains to the stronghold.

True to his word, on Oct. 11 Cochise held a council to get their input. He and his captains finally agreed to make peace as long as the reservation contained the Dragoon and Chiricahua mountains, the government provided them with sufficient food and other rations, and Jeffords served as their agent.

Jeffords had served Howard well. Cochise welcomed peace and promised his band would commit no further depredations in southeastern Arizona Territory. Despite skepticism from nearly every white American near the newly established Chiricahua Apache Indian Reservation, the treaty held. The sole legitimate complaint came from Mexico, for the Chiricahua bands on the reservation—Cochise’s Chokonens, Juh’s Nednhis and Geronimo’s Bedonkohes—continued to raid into Sonora and Chihuahua.

MEXICAN RAIDS

Mexican authorities complained to the Departments of State and War in Washington about raids originating from the reservation. Although Cochise himself did not participate in any of these depredations, many of his band members did continue to raid below the border. Jeffords adopted Cochise’s view that Mexico had not sought a treaty with the Chiricahuas.

Worse yet, the agent reportedly admitted to editors of the Arizona Citizen, “He did not care how many Mexicans ‘his people’ (as he paternally called them) killed in Mexico; that for acts of treachery with those Indians the Mexicans deserved killing.” Jeffords later clarified that such was his private belief and not his public stance. But the insensitive comment did little to stem the Apaches’ bloodlust against northern Sonorans, most of whom were innocent victims.

In late 1873 Cochise and Jeffords finally ordered the Chiricahuas to either refrain from raiding or leave the reservation. The Bedonkohes and most of the Nednhis chose to return to northern Mexico, and the raids tapered off. Then, on June 8, 1874, Cochise died of what was probably stomach cancer, and his eldest son, Taza, succeeded him as chief. But the son lacked his revered father’s authority. That fall discontented Chiricahuas splintered off from Taza’s band, and over the next year they resumed the raids into Mexico.

A BROKEN PEACE

A relatively minor incident in 1876 proved the breaking point. That April 6, north of the border at Sulphur Springs, Chokonen warrior Pionsenay bought whiskey from rancher Nick Rogers, returning the next day with his nephew to demand more. When Rogers refused to sell them more whiskey, the pair killed the rancher and his partner and ransacked their house. That set off a firestorm of events, prompting authorities in Washington to ultimately fire Jeffords as agent and close the Chiricahua reservation.

Some 300 Apaches under Cochise’s sons, Taza and Naiche, went to San Carlos, while 400 others under Gordo, Chatto, Esquine and Zele traveled to Ojo Caliente in New Mexico Territory to join Victorio’s Chihennes. Those living in Mexico soon resumed their raids into southeastern Arizona Territory. The peace was broken.

In 1892 Jeffords settled on a ranch near Owl Head Buttes, some 35 miles north of Tucson. He died there on Feb. 19, 1914, and was buried in that city’s Evergreen Cemetery, where officials dedicated a monument to him in 1964. Novelist Elliott Arnold related the Arizona Territory saga of Jeffords, Cochise and Howard in his 1947 book Blood Brother, which was adapted into the 1950 film Broken Arrow—starring James Stewart as Jeffords and an improbable Jeff Chandler as Cochise—and a TV series of the same name later that decade.

Edwin R. Sweeney of St. Charles, Mo., writes often about the Chiricahua Apaches. He is the editor of “Making Peace With Cochise: The 1872 Journal of Captain Joseph Alton Sladen” and the author of “Cochise: Chiricahua Apache Chief and From Cochise to Geronimo: The Chiricahua Apaches, 1874–1886,” which are recommended for further reading.

This article originally appeared in the April 2017 print edition of Wild West.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.