At a swanky Manhattan meeting, black leaders told Bobby Kennedy off

The best clue to where participants at the gathering stood was where they sat. All 11 Negroes lined up on one side of the drawing room at 24 Central Park South in New York City, the five whites on the other. The divide was fitting for May 24, 1963, when demarcation of the races was written into law across the South and into practice in the rest of America.

But the split was not auspicious. Novelist James Baldwin had pulled together the group—fellow artists, academics, and second-tier civil rights leaders, along with his lawyer, secretary, literary agent, his brother, and his brother’s girlfriend—at U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy’s request. The aim was to talk openly about why rage was building in northern ghettos and why mainstream civil rights leaders couldn’t or wouldn’t quell that rage.

A second sign that the meeting was ill-fated was who had not been invited. Martin Luther King Jr. wasn’t welcome, nor were the top people from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Urban League, because the attorney general wanted a no-holds-barred critique of their leadership. He also hoped to discuss what President John F. Kennedy’s administration should do, with Negroes who knew what the administration was already doing. A serious conversation without the serious players would have been hard enough, but Bobby made it even harder: What he really wanted was not candor, but gratitude. Baldwin did his best given those constraints and only one day’s notice. Bobby may not have been inclined to take the black participants seriously, yet each of them—whether matinee idol or crooner, dramatist or therapist—had earned their stripes as activists.

After feeding his guests a light buffet and settling them in chairs or on footstools, Bobby opened the discussion on tame and self-serving notes. He listed all that he and his brother had accomplished in advancing Negro rights, explaining why their efforts were groundbreaking. He warned that the politics of race could get dicey with voters going to the polls in just 18 months and conservative white Democrats threatening to bolt.

“We have a party in revolt and we have to be somewhat considerate about how to keep them onboard if the Democratic Party is going to prevail in the next elections,” said the attorney general. Kennedy had already implied that he was among friends by tossing his jacket onto the back of his chair, rolling up his shirtsleeves, and welcoming everyone into his father’s elegant apartment. Now he wanted these friends to explain why so many of their Negro brethren were being drawn to dangerous radicals like Malcolm X and his Black Muslims.

The first reaction was polite and tepid. Bobby assumed his audience was naive about the rawboned world of politics; his audience took him to be too credulous on the rawer realities of the slums.

“He had called the meeting in hopes of persuading us that he and his brother were doing all that could be done,” remembered Lena Horne, whose voice had earned her center stage at the Cotton Club and whose left-leaning politics had gotten her blacklisted in Hollywood. “The funny thing was that no one there disputed that. It was just that it did not seem enough…He said something about his family and the kinds of discrimination it had had to fight. He also said he thought a Negro would be president within 40 years. He seemed to feel that this would establish some sort of identification, some sort of rapport, between us. It did not…The emotions of Negroes are running so differently from those of white men these days that the comparison between a white man’s experience and a Negro’s just doesn’t work.”

Kenneth Clark, black America’s preeminent psychologist, had done the research on how color barriers harmed black children that helped push the Supreme Court to outlaw segregated schools. Clark had come to the meeting prepared to lay out studies and statistics showing that corrosive racial divide, but he never got the chance. Jerome Smith, a 24-year-old Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) activist from New Orleans who had held back as long as he could, suddenly shattered the calm, his stammer underlining his anger.

“Mr. Kennedy, I want you to understand I don’t care anything about you and your brother,” Smith began. “I don’t know what I’m doing here, listening to all this cocktail party patter.”

The real threat to white America wasn’t the Black Muslims, Smith insisted—it was when he and other advocates of nonviolence lost hope. Smith’s record made his words resonate. As a Freedom Rider and CORE organizer, he had suffered as many savage beatings as any civil rights protester had, including one for which he was now getting medical care in New York. But his patience and his pacifism were wearing thin, he warned. If the police came at him with more guns, dogs, and hoses, he would answer with a weapon of his own.

“When I pull a trigger, kiss it goodbye,” Smith said.

Kennedy was shocked, but Smith wasn’t through. Not only would young blacks like him fight to protect their rights at home, he said, they would refuse to fight for America in Cuba, Vietnam, and any of the other places where 0the Kennedys saw threats.

“Never! Never! Never!” Smith declared.

“You will not fight for your country?” asked the attorney general, who had lost one brother and nearly a second at war. “How can you say that?”

Smith replied that just being in the room with Kennedy made him nauseous. Others chimed in, demanding to know why the government couldn’t get tougher in taking on racist laws and ghetto blight. Lorraine Hansberry, author of A Raisin in the Sun, stood to say she was sickened as well.

“You’ve got a great many very, very accomplished people in this room, Mr. Attorney General, but the only man who should be listened to is that man over there,” Hansberry said, pointing to Smith.

Three hours into the evening, the dialogue had become a brawl, with Smith setting the tone.

“He didn’t sing or dance or act. Yet he became the focal point,” said Baldwin. “That boy, after all, in some sense, represented to everybody in that room our hope. Our honor. Our dignity. But, above all, our hope.”

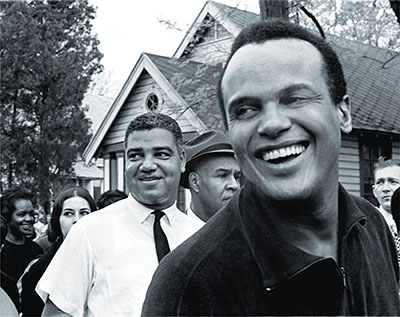

Kennedy had heard enough. The attorney general’s demeanor let everyone know the welcome mat had been taken up. His flushed face showed how incensed he was. As the guests were leaving, Harry Belafonte approached Kennedy. Bobby considered Belafonte a loyal friend.

“Well, why didn’t you say something?” Kennedy asked the singer. “If I said something, it would affect my position with these people, and I have a chance to influence them,” Belafonte replied. “If I sided with you on these matters, then I would become suspect.”

Before Belafonte could finish his thought, Kennedy turned away.

“Enough,” the attorney general grumbled.

Neither side got what it wanted. The blacks had grasped the chance to vent their rage—one reason they’d come on such short notice. They had also hoped to remake this well-meaning brother of a president into an ally, not for his incremental reforms but for breakthrough change. The blacks believed they had not only failed but that they had burned the bridge they had come to build.

“We left convinced that we had made no dent or impact on Bobby,” said Clark. “It may very well have been that Bobby Kennedy was more antagonistic to our aspirations and goals than he was before, because the clash was so violent…This was tragic.”

Bobby came away with even less. He had let temper win out over compassion. He had asked for candor but had stopped hearing as soon as fingers pointed at him. What Smith and the others said should not have come as a surprise. Their remarks mirrored what Baldwin had written six months earlier in an acclaimed New Yorker article that Bobby had read. In the piece, Baldwin explained why it was not hard for him “to think of white people as devils,” but he offered hope: “We may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare.”

Neither the attorney general nor his guests that night sensed that Robert Kennedy would soon be counted among that handful. A born fighter, Bobby first reacted to the meeting by jabbing back. “They don’t know what the laws are—they don’t know what the facts are—they don’t know what we’ve been doing or what we’re trying to do. You can’t talk to them the way you can talk to Martin Luther King or [NAACP executive secretary] Roy Wilkins,” he told historian Arthur Schlesinger, forgetting that his own frustration with King and Wilkins had made him ask Baldwin to gather other black voices.

And there was more.

“None of them lived in Harlem,” Kennedy told another interviewer. “I mean, they were wealthy Negroes.”

Kennedy’s own wealth, of course, dwarfed his guests’, and fame didn’t exempt them from the humiliations every dark-skinned American faced. Worse still, to Bobby, three of that evening’s black guests “were married to white people,” which Kennedy said exacerbated their insecurities and encouraged them to talk tough. His conclusion: “I should not have gotten involved with that group.”

Both sides had agreed not to talk to the press but neither could resist. The New York Times reported that the “secret” meeting had been a “flop.” Baldwin told the paper that the attorney general “didn’t get the point” when he and others had urged that JFK address the nation on Negro rights and otherwise step up his engagement. Robert Kennedy didn’t talk to that reporter, but he did speak to a friendlier writer at the Times: columnist James Reston, who in an op-ed essay positioned Kennedy precisely where Reston saw himself—caught between the rock of “militant white segregationists” like the Kennedy administration’s Democratic allies in the South and the hard place of “militant Negro integrationists” like those at the Baldwin meeting. Reston worried along with the attorney general “that ‘moderation’ or ‘gradualism’ or ‘token integration’ were now offensive words to the Negro, and that sympathy by a Negro leader for the administration’s moderate approach was regarded as the work of ‘collaborationists.’”

Reston had it partly right. In its first two years, the administration had walked a calibrated and overly cautious middle path on civil rights. JFK had promised while running in 1960 to sign with “a stroke of a pen” an order banning discrimination in housing, but he took so long that protesters launched an “Ink for Jack” campaign, mailing the president hundreds of fountain pens. Jack and Bobby named too many racist judges, took too long to file a serious civil rights bill, and left the black voters who had pulled them to victory in 1960 looking for more forceful answers. While moderation might have been the smart approach for a White House hell-bent on reelection, it made less sense for the commander of the New Frontier’s riot squad.

In Robert Kennedy’s earlier years, the disastrous meeting at Joseph Kennedy’s Manhattan pied-à-terre might have been the end of the story. But after he fumed for a couple of days, Smith’s tirade began to sink in for the former ambassador’s son. “I guess if I were in his shoes, if I had gone through what he’s gone through, I might feel differently about this country,” Bobby now told friends.

This was not empty talk. The day of the Baldwin get-together, the attorney general had urged owners of national chain stores to voluntarily integrate their lunch counters below the Mason-Dixon Line. Days before, Kennedy had helped broker a settlement on desegregation and employment that partly defused violence in Birmingham, Alabama.

Bobby Kennedy was stretching himself. He still brooded, but he was learning to channel his rage into outrage. Instead of deriding critics like Baldwin and Smith, which had been his first impulse after they attacked him, Kennedy found himself identifying with them. Seeing the effects of racism, he began searching for causes. Instincts like those had led him to spring Martin King and Junius Scales, leader of the Communist Party USA, from behind bars. Increasingly Kennedy’s words and actions on race would take on the very element of moral indignation that Lena Horne and Lorraine Hansberry had pleaded for. Bobby already knew that bigotry wasn’t confined to the South, but he now acknowledged that not just America’s laws but America’s soul needed redemption. Eventually, RFK would emerge as the only white politician who could talk to Black Muslims and to black mothers.

Looking back, Kenneth Clark conceded he and his allies had underestimated the attorney general.

“Our conclusion that we had made no dent at all was wrong,” Clark said.✯

From the book Bobby Kennedy: The Making of a Liberal Icon by Larry Tye. Copyright @ 2016 by Larry Tye. Reprinted by arrangement with Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

This excerpt was originally published in the November/December 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.