In December of 1943 Anthony “Tony” Procassini was a few credit hours short of graduating from the University of Michigan when he walked into a recruiting station and volunteered to serve.

Initially hoping to join the Coast Guard to stay close to Michigan, Procassini was told that his options were either the Navy or the Marine Corps — Procassini chose the Marines.

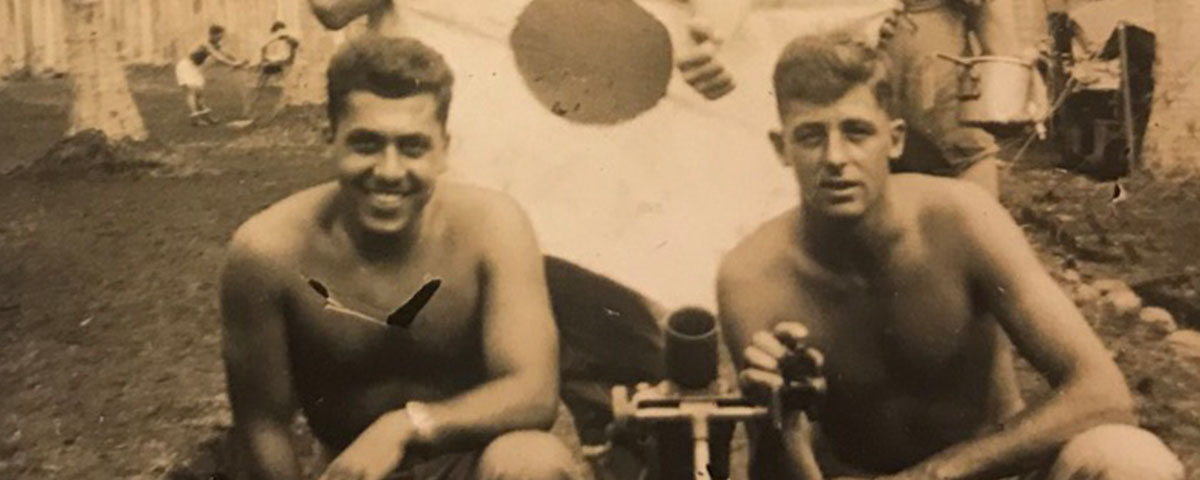

As a mortar crewman assigned to the 1st Marine Division, Procassini was shipped to the rest area island of Pavuvu in the lead up to the invasion of Peleliu. Pavuvu wasn’t paradise found, according to Procassini.

“I thought, what a hell hole,” he told HistoryNet.

Procassini was among the first to land at Peleliu on September 15, 1944, under the overall command of legendary Col. Lewis “Chesty” Puller.

“We thought it would be over in five or six days,” Procassini said. “We were there for several weeks before being relieved…It was a tough invasion. Tough fight. They fought us from the time we were on the beach until we crossed the island.”

On Peleliu, the 1st Marine Division suffered a 56 percent casualty rate, but miraculously Procassini emerged unscathed.

“When we got back to Pavuvu I thought, ‘oh, what a beautiful island,’ ” Procassini quipped.

Reoutfitted, the 1st Marine Division prepared for their next battle — Okinawa. The island was deemed crucial by American planners in order to sever the last southwest supply line to mainland Japan. The island would also be a key base for American medium bombers in the event of an invasion.

On April 1, 1945, Procassini was part of the first wave of 60,000 Marines and soldiers of the U.S. Tenth Army to land on the island.

The Marines and infantrymen faced little to no resistance upon landing, a fact that was eerie for the veterans of Peleliu.

An entrenched enemy — 155,000 strong — operating out of a labyrinthian network of caves and tunnels, awaited them.

“When we got in, we faced very sporadic resistance — the first day, the second day. And then after that we began hearing that the Army units were having trouble,” said Procassini.

The initial job of the 1st Marine Division was to secure the central region of the island, while the 6th Marine Division secured the north and the Army secured the south.

“We were assigned to go and relieve the units down there. That’s what we did,” he recalled. “When we got down there, the situation was hot. We stayed there until they said it was secure, although it probably wasn’t very secure.”

Despite the grisly conditions, Procassini and his fellow Marines still found humor in the misery — “we would sleep in the caves and in the morning you would come out and, pardon the expression, you’d dropped your drawers. Fleas would just jump out by the thousands. You had to laugh,” he recalled.

The brutal campaign would last 82 days, but for Procassini, his fight would end on May 14.

“We were on a ridge — I don’t remember the exact ridge — and the enemy opened up with a bombardment of artillery fire,” Procassini told Michigan Today. “A shell landed close by and exploded, resulting in a blast concussion. I had no idea how long I was out.”

Sent to a field hospital, Procassini would return to the front lines on June 1, but by the time he fully recovered, the battle at large was over.

Following the Japanese surrender, Procassini was promoted to corporal and stationed in China for six months — despite having enough points to go home.

Returning stateside on January 1, 1946, Procassini was honorably discharged a month and a half later.

He would go on to finish his bachelor’s degree in psychology at the U of M and raise ten children with his wife, Marguerite Dawn Trombley.

For Procassini, his service was not about medals or awards. It wasn’t until 2018, after being questioned by his granddaughter as to whether he received a Purple Heart, something every wounded combat veteran is entitled to, that he and his family began to look into it.

“[The Purple Heart] is one of those things I never thought about very much,” Procassini told Michigan Today.

But it meant something to his family, and after getting the “run around” by the National Records Center, Procassini took his case directly to General Robert Neller, then-Commandant of the Marine Corps, in April 2019.

Neller expedited the process and, 74 years after Okinawa, on July 12, 2019, Lt. Col. John Gianopoulos, of the 24th Marine Regiment, 1st Battalion, awarded 98-year-old Procassini with the Purple Heart.

“There are not a lot of Americans who have smelled the taint of blood, whether it is their own or the enemies, and have smelled the Cordite, the sweat and the fear of battle,” U.S. Marine Sgt. Major Adam Ruiz said during the medal presentation. “I’d like to say ‘thank you’ to those veterans who know that.”